Horror is a genre that consistently finds inventive ways to approach and reinvent other genres. For instance, though the first quarter of the year is often mocked as a movie dumping ground, the horror genre has absolutely owned winter 2017 with hits like Split and Get Out reinventing the cinematic universe mapping process and the socially conscious drama by infusing them with horror tropes. Last year by this time, the most talked about film not named Deadpool was The Witch, which dropped us into a period specific colonial setting and presented the Puritan fears of an evil witch in the woods as an absolute truth.

Horror has consistently reinvented itself each decade, particularly from Psycho onward. Sure there are still your standard slashers and home invasion films being made and a few quite robustly aligned with the classical tropes, but the buzziest horror films find a new prism to enter the genre.

In 1980, horror birthed a new American genre of the erotic thriller with Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill. There were throats being slashed, but there were also haunting scenes of sexuality shown as psychological desperation. The body being carved to start the film wasn’t a co-ed at a party or sleepover, but instead a bored housewife (Angie Dickinson) who isn’t able to arouse her husband and instead sadly ventures to a museum with desperate hopes of an affair; she’s killed by a man wearing woman’s clothes, shortly after engaging in public sex with a stranger.

What makes the erotic thriller different than giallos—Italian slashers that often showed women enjoying the pleasures of sexuality before having their throat slit—is that they wrestle with the puritan American guilt of enjoying sex without procreation. The women are shown enjoying sex or enjoying the attention that they can receive from displaying their body in a specific way and the men and women who murder them are on a mission to eradicate pleasure because they feel none themselves or they feel shame for their desire, shame of their jealousy of those who are freer with their bodies. This shame is very much a part of our American identity; sure we peddle sex and desire and build massive industries built on them, but we frequently battle against each other for the highest moral grounds whenever a sex scandal breaks or whenever a political party tries to make it harder for women to have access to birth control but easier for older men to keep their medically infused erections insured.

You’re wondering what this has to do with Basic Instinct on its 25th anniversary? Everything. The erotic thriller was a staple of adult American cinema from the 80s through the mid 90s and now it no longer exists. But Paul Verhoeven’s film is one of the only erotic thrillers that show us that there’s a new angle to play within the genre. It’s the only big erotic thriller that allows the woman to talk about her pleasure, change a man’s view on his role within pleasure and also survive to the very end, still espousing her desire to live a life full of sex, but without having children. Not only does she not get punished for her sex life, but also she kills; her agency isn’t just in whom she fucks, but also in whom she decides can live to fuck again.

The decline of the big budget erotic thriller runs parallel to the rise in online pornography. The erotic thriller provided an avenue of viewing sexuality and alluring scenarios without having to endure the potential shame of going into the back room of the video store, being spotted by a co-worker closing the door, videos in hand. The erotic thriller gave similar credence to reading Playboy for the articles (because hey, they did have some of the greatest authors penning stories for them, and more probing actor interviews) because many of these films were directed by filmmakers of obvious talent (De Palma, Verhoeven, Lawrence Kasdan, Alan Parker, etc.), thus you watch them for the story. But in the same way that the flood of online pornography ruined print magazine such as Playboy, so to did it remove the potential shame of going to the back of the video store or purchasing a ticket in public for a skin film. But we’ve actually lost a great subgenre of film.

Don’t laugh, I can feel you starting to laugh.

The idea that pornography has made the erotic thriller obsolete reveals a bit of our Plymouth Rock bonneted background. Sex is more than a physical act; it’s psychological, it’s revealing of a person, it opens the door to obsession, guilt and many hard to process emotions; it’s a major life pursuit that dictates other behaviors and presentations in life. We have dating apps whose very purpose immediately switched from being perceived as for dating and instead are most often perceived as for hookups. We have a young generation that’s currently experimenting with sex and relationships not only less than any other modern generation but also in a more distant way than ever before. By choosing sexual presentations largely into one mode, hard pornography, and by reducing tools meant for dating just to hookups, we’re creating a pretty warped view of sexuality. Modern film and television largely uses sex scenes to show a power struggle where one person desires it at the moment and the other doesn’t, or as the physically self-involved way to end an argument. Movies and TV seem to have forgotten that sex can actually be fun. Where has the presentation of pleasure gone? Even though there’s death in Instinct, sex with Catherine Trammell (Sharon Stone) is always presented as supremely enjoyable for both people involved.

A deft filmmaker like Verhoeven can show the power dynamics and character changes through the actions before, during and after sex. For the reasons listed above, this genre might be needed now more than ever before; but most importantly, it’s an overlooked genre that allows directors to explore things that they wouldn’t be able to in another genre. It’s not just the dirty cousin to horror. Historically, horror has often been written off as not a serious genre until directors do something different with it and the erotic thriller could and should be an avenue for a director to do interesting work. And Basic Instinct is a great place to start to show how it doesn’t have to be misogynist or punishing of women to achieve a thrilling film.

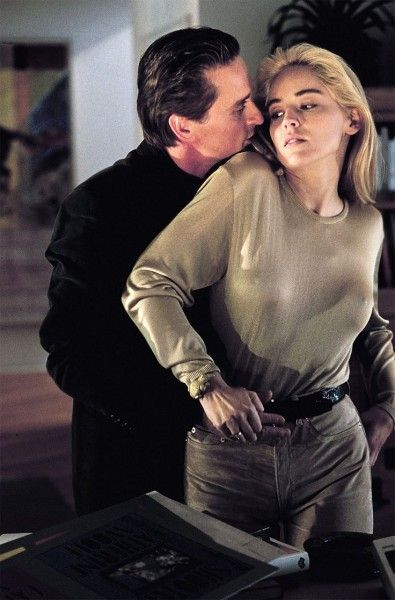

Although it opens with a tied to the bed sex scene that immediately gives way to a graphic killing (icepick through the eyeball!) and the plot features many red herrings and misdirections, Basic Instinct is tapped into many interesting insights into its two main characters sex lives and how they define them as a person. Catherine Trammell, the alluring author who maintains sexual relationships with men and women for years, is threatening to many men not just because she’s written about (and possibly used) an icepick to murder during the throes of coitus, but also because she’s fully in charge of the when, how and where of the actions. After one of her lovers has been murdered with an icepick while tied nude to his bed, semen all over the sheets and traces of cocaine found on his penis, Trammell is interrogated at the police station. Everyone focuses on her leg crossing during this scene, because Stone wears no underwear, but what’s most important are the reactions of the men in the room. Between the legs uncrossing and her admission that she’s sad the man is dead “because I liked fucking him,” the interrogators are all sweat and open mouths, but not necessarily desire. Her frankness about her sex life is both arousing but also threatening.

With Verhoeven’s careful direction, Catherine isn’t merely a black widow that ensnares men with her sexuality and kills them. She retrains their bad sex habits. Before she seduces the lead detective on her case, Nick Curran (Michael Douglas), we see him have forceful sex with the department psychologist (Jeanne Tripplehorn). The therapist is initially a participant in the seduction, but eventually Nick overpowers her, bends her over while she says “no, not like this” and the sex becomes one-sided and for him alone.

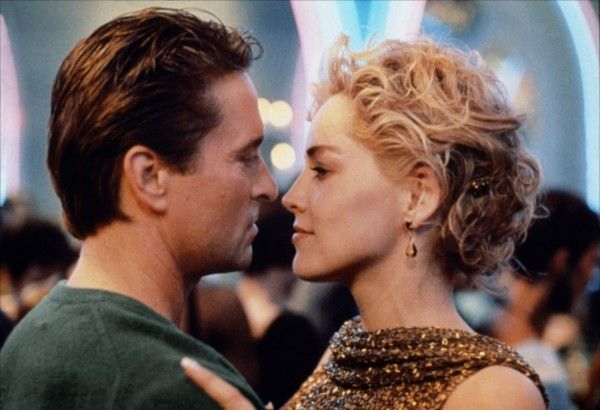

When Nick has sex with Catherine, during a routine house call for the investigation of course, he calls it “the fuck of the century” and Catherine laughs at his machismo and re-labels it “a good start.” Their sex is very different. Nick attempts to take full control at the start but Catherine is able to exert herself in a manner that not only slows him down but also shows that this is going to be a two-way session. He performs oral sex first, she second; they each get a chance on top and he allows himself to be tied up, giving her full control but also trust since she is a murder suspect. The result is a different type of lay for Nick, one that’s inclusive and alluring and one that he labels as being beyond exceptional (because every man needs to feel like the sex he just had was right up there with the best that’s ever been had) and she sees as a beginning to a trusting and fulfilling liaison.

Other than giving the woman full sexual power, which she then makes a level playing field in bed but disproportionately holds power out of the bed (cue the jealousy of Roxy and Nick), what differentiates Basic Instinct from the De Palma erotic thrillers of the 80s is that Verhoeven fully embraces the film noir undertones. This is a film that shows the femme fatale that Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe heard sexual innuendos from. And while films like Kasdan’s Body Heat and Jim McBride’s The Big Easy got to play that angle too, Verhoeven steeps his film noir tea bag in a boiling hot horror narrative. The kills are gruesome, and as I’ve given previous ink to Verhoeven—who made many sexy Dutch films that didn’t require gruesome violence to get financed—here he gets to directly show how prude Americans are in relation to sex, needing murder to accompany with it to make it feel like it’s a worthwhile story.

There’s a repeated line in Basic Instinct that Curran’s life goal with Catherine (after the Fuck of the Century™) is to “fuck like minx, raise rugrats, live happily ever after.” He says this line twice to Catherine. And each is important for a different reason. The first time, he offers it as an ending for Catherine’s new book about Curran’s own police scandal. She counters that that ending “won’t sell, somebody has to die.” This itself is a sly comment that American audiences need death to be entertained. Even sex isn’t enough of a thrill; someone has to be punished by the end.

The second “minx, rugrats, happily ever after” line comes as some Curran post-sex pillow talk and Catherine responds, “I hate rugrats.” To which Curran shrugs off and says “fuck like minx, then.” They embrace and the camera pans under the bed to show an icepick. This exchange, written by the not so great at dialogue and/or plotting big money pen of Joe Eszterhas, is much more important to the future life force of the erotic thriller genre than you might think. In essence, Catherine is able to circumvent American movie rules that require a woman who has multiple sexual partners, enjoys fornication and takes pride in her naked body is able to continue living as such, without having to learn the errors of her ways or die in her pursuits of pleasure. She’s both a promiscuous final girl and a killer. For “family values” America, it’s rather shocking and subversive to have Catherine’s final dialogue be that she doesn’t want to have children—she just wants to have sex and then reveal that like the victim from the beginning, she’ll continue to let the man in her bed live because, for now, “I like fucking him.”

Laugh all you want, but the erotic thriller is a genre where good directors and actors can really sink into psychology, deliver some thrills and provide commentary on our societal hypocrisy. It’s something that, like horror, is a fertile playground for new ideas and provides the potential for some ribald water cooler conversation. Basic Instinct is the perfect place to start for a genre overhaul. It chips away at the conventions with an icepick. Now if only a brave studio will entrust someone like Blumhouse to deliver on the cheap, we’d have a revival on our hands. And yes, the interest would purely be for the stories.