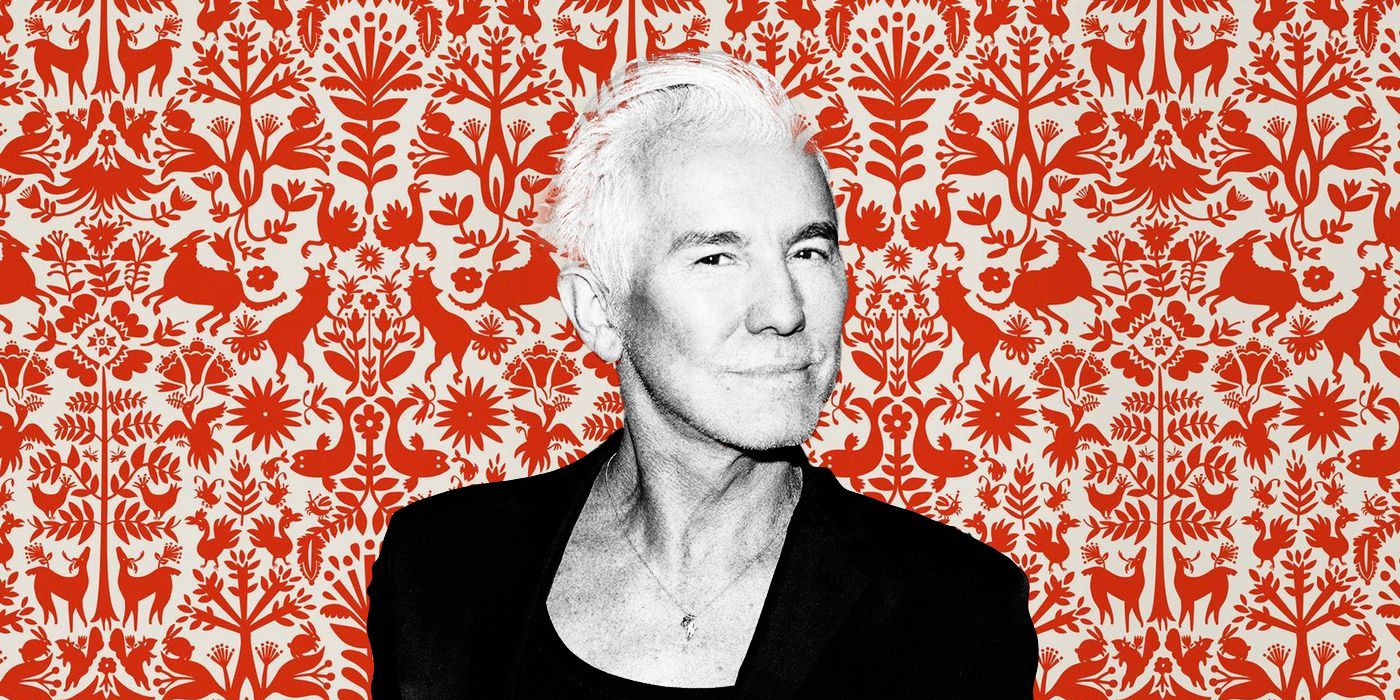

Perhaps one of the most fascinating trends in the hypnotically hyper-stylized career of Australian auteur Baz Luhrmann comes in the form of his recent fascination with American cultural mythology. Over the past decade, Luhrmann has deftly shifted his cinematic output away from postmodern reinterpretations of a Shakespeare classic and the tumultuous magic of Montmartre at the turn of the century to focus on the elusive and disillusioned concept of the American Dream. Although Romeo + Juliet’s revisionist Southern California setting allowed Luhrmann to begin to explore the dying dream of American opportunism through the thwarted romance of the titular couple, both The Great Gatsby and Elvis see Luhrmann deconstruct the concept of the self-made man and the tragic complexities of fame and capitalism, respectively. Although his divisive aesthetic is often discredited by critics and audiences as a superficial engagement with cinematic style, Luhrmann’s stylistic excess throughout The Great Gatsby and Elvis is essential to each film’s storytelling substance. By unraveling pop culture mythmaking through perceived superficiality, Luhrmann mobilizes glittery maximalism as a symbolic technique for critiquing the American Dream.

Although Baz Luhrmann’s unconventional approach to adaptation sees The Great Gatsby transform from its legendary status in the American canon into a gold-crusted CGI-enhanced spectacle of lost innocence, it is essential to acknowledge the intentionality of Luhrmann’s excess. Rather than merely aiming for period accuracy when visually compiling all of the details of Fitzgerald’s great novel, Luhrmann imbues every inch of set design and every stitch of costuming with the essence of Roaring Twenties idealism. By transposing the intricacies of Gatsby’s glamorous façade into the digitally rendered dreamscape of mid-twenties New York, Baz builds a multilayered world of eye candy that points towards the self-mythologizing that Gatsby hopes to uphold throughout his nuanced narrative. In particular, the lavish parties on Gatsby’s West Egg estate were shot for 3D projection, encapsulating Luhrmann’s desire to bring the audience into a space of sensory self-indulgence similar to Gatsby’s rich guests.

Although the spectacular immersion provides an entry point into the raucous behavior and dramatic thrills of the narrative, The Great Gatsby’s emphasis on eye-popping opulence also implicates the audience in the tragic trajectory of Gatsby’s unraveling, building dramatic tension through the slow decay of the film’s shimmering visuality. Descending towards the devastating line of deaths that conclude Fitzgerald’s narrative following the climactic confrontation between Gatsby (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Tom Buchannan (Joel Edgerton) in a suite at the Plaza Hotel, the filmmaker allows the film’s golden hue to fade into a green shadow, evoking the oft-discussed green light imagery through a ghostly presence in the color grading. While the green light symbolizes the thwarted dreams of Gatsby’s status as a purportedly self-made man within the system of American capitalism, Luhrmann layers green over the final act of the film to emphasize a moral mildew that spreads across the spectacle. Although his over-the-top aesthetic initially seems to be a mismatch between director and subject matter, Luhrmann proves himself worthy of the Great American Novel through his subversive focus on the superficiality bubbling underneath the mythology of Gatsby and the Lost Generation.

If The Great Gatsby saw Luhrmann successfully pivot towards a disintegration of the American Dream through symbolic glitz and digitized spectacle, Elvis nearly perfects the humanizing power of Luhrmann’s engagement with American excess. Rather than honing his skills for maximalist storytelling to propagate the superhuman mythos of Elvis Presley as the King of Rock and Roll, Luhrmann uses the glittering lights of Las Vegas and rockstar vibrancy of Presley’s persona to embody the gilded cage in which Colonel Tom Parker ensnared Elvis throughout his career. While Austin Butler’s toweringly empathetic and uncannily possessed performance as the titular icon propels the film’s efforts to humanize Elvis, Luhrmann’s meticulous and mesmerizing recreations of both public and private moments in Presley’s life effectively nuances the film’s retelling of Elvis’s complicated life. By formally emphasizing the surface-level glamor of Elvis’s rapid rise to fame through colorful costuming and stunning set design as well as rapid-fire editing and split-screen cinematography, Luhrmann draws upon the cultural legacy and pop iconography of Presley’s career to comment on the price of fame and pitfalls of capitalist exploitation.

In many ways, Elvis directly calls upon the tragic narrative of The Great Gatsby to reframe Presley’s humanity in the midst of his heartbreaking downfall due to his insurmountable fame. By presenting Elvis’s story through the slippery perspective of Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks), Luhrmann echoes the framing of Gatsby’s life within Nick Carraway’s unreliable narration, critiquing the storytelling superficiality of the complicated narrators through his own subversive spectacle. Furthermore, even as both The Great Gatsby and Elvis provide dynamic visions of their titular icons, Luhrmann casts the timeless tales as both Shakespearean tragedies and pop operas, allowing for meaningful melodrama to embellish the emotional centers of both stories. In addition to the unreliable narration swirling in the soundscape of both motion pictures, Baz’s fusion of contemporary music and period-specific songs render the filmic fantasies as atemporal meditations on the American dream, bridging the gap between the stories of the past and the present-day viewers. While the inclusion of artists like Kanye West and Lana Del Rey provides a diverting aesthetic difference to his retelling of Gatsby, Luhrmann’s layering of real Elvis recordings, new hip hop tracks featuring Elvis samples, and especially Austin Butler covering young Elvis performances allow the film to elevate the legacy of Presley’s musical output and the Black artists that paved the way for his rock-and-roll sound.

Even as Baz Luhrmann’s transition towards demythologizing the American Dream may initially seem like a surprising shift away from films like Moulin Rouge and Australia, both The Great Gatsby and Elvis boldly embody the director’s vitality in reframing seemingly untouchable cultural staples. Through the 3D rendering of an essential 1920s tragedy to the kaleidoscopic retelling of the rise and fall of The King of Rock and Roll, Luhrmann endlessly transforms the cinematic form into a reflexive collage of symbolic visuals and stunning stories. By engaging with the aesthetic superficiality of Gatsby’s parties and Elvis Presley’s Vegas years, Luhrmann’s most recent films fantastically conquer claims of empty excess to reveal an erupting visual vibrancy that meaningfully decodes the structures of the American Dream. Although The Great Gatsby and Elvis render their titular figures in all of their sumptuous Shakespearean sadness, Luhrmann somehow maintains a balance of entertaining excess and emotional resonance, allowing his handling of heavy themes to always remain equally resonant and resplendent.