From director Barry Levinson and based on the incredible true story of Harry Haft, The Survivor tells the story of a man (brought to life through a superb performance by Ben Foster) who, after surviving the horrors of Auschwitz where he was forced to compete in brutal boxing matches with his fellow prisoners, seeks to build a new life for himself. Driven to find someone from his past, he’ll never be able to fully connect with his own family until he reconciles with what he survived at the hands of his captors.

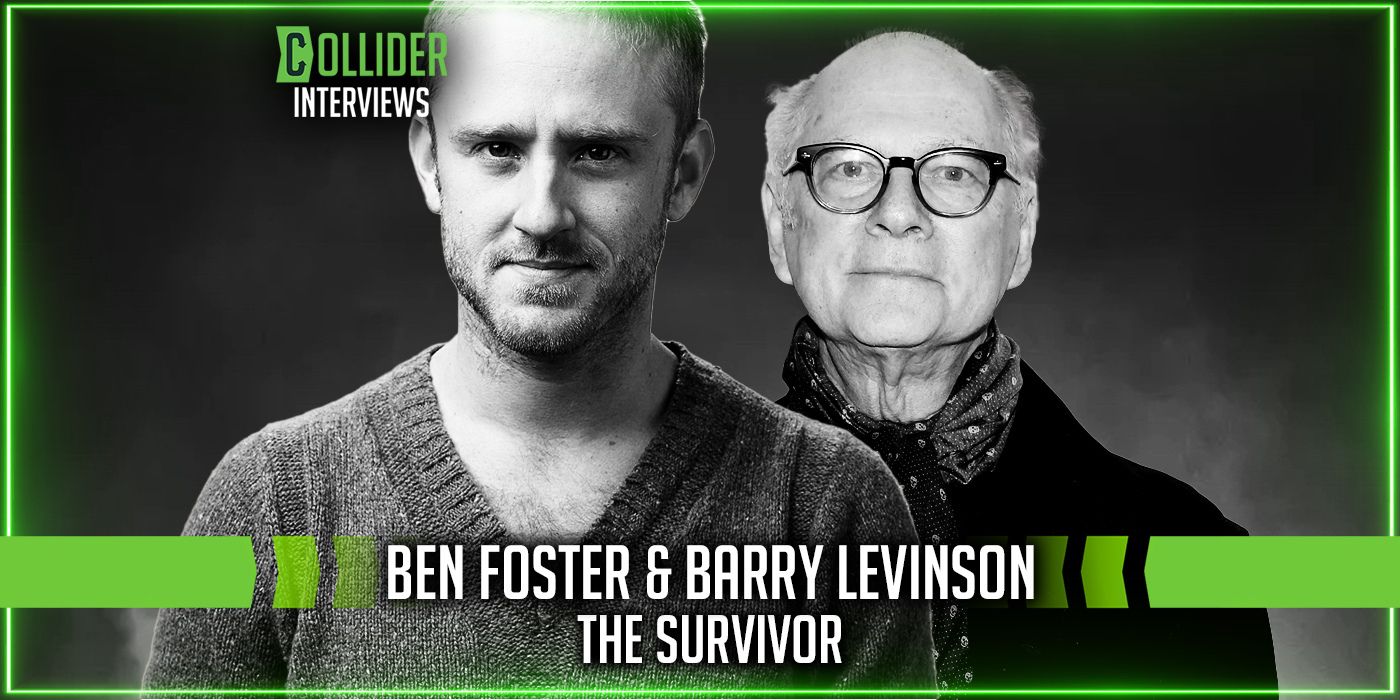

During this interview with Collider, the mutual respect between actor and director was apparent as Foster and Levinson talked about reuniting on this project, 20 years after their first time working together, the reaction they had to reading this script, the drug of acting, how Mel Brooks led to Levinson making Diner, the evolution of Rain Man during the writers’ strike, what it was like to shoot the concentration camp scenes, how Foster hopes it doesn’t take another 20 years to work with Levinson again, and the jarring similarities between The Survivor and his next film, Emancipation.

Collider: First of all, tremendous work on this. I was in tears throughout much of this, just because of the story that it is. You both did such tremendous work on this film, so thank you for that.

BARRY LEVINSON: Thank you.

BEN FOSTER: Thank you.

Barry, when this script came to you, was it something that you read right away and were immediately interested in? Was it something you had for some time before you read it? How do you work when scripts come your way? Do you tend to read them right away?

LEVINSON: I try to. It’s not always possible because of the situation that you might be in. If I’m getting a script when I’m filming, it’s really hard for me to focus, so I generally have to wait until I would finish, during that period of time. All you wanna think about is the film [that you’re making]. It stays in your head all the time because you don’t wanna miss something. There’s nothing worse than shooting a scene, and then going, “Oh, I forgot to put in this or that.” So, the long answer to that is I read it, probably within a couple days of getting the script.

Was it something you were immediately interested in and saw yourself doing?

LEVINSON: I never thought of myself as doing this type of film. It wouldn’t have occurred to me. But I got the script and I read it, and then I remembered something that I had completely forgotten about from when I was a kid. I was five years old, or something like that, and it was, I’m guessing, 1948 or 1949, and this man showed up at the house. It turns out it was my grandmother’s brother. I lived with my parents and my grandparents, and I never knew that she had a brother. I didn’t know anything about any of this. I didn’t know who he was. He stayed for two weeks and they put him up in my bedroom on a cot, on the other side of the room.

The first night, I woke up because he was tossing and turning and yelling, and speaking in a language I’d never heard, and then he’d fall back asleep. It went on night after night after night, and he was with us for about two weeks, and then he left. No one talked about him, at least when I was around. He moved on. And then, I was about 16 and I was sitting in the kitchen talking to my mother, and she mentioned him being in a concentration camp. The minute she said that, I immediately flashed back to when I was a kid, and that’s what it must have been. He was haunted by what took place, and he would be tossing and turning. I didn’t know what he was saying, but that’s what had to be going on.

When I got this script, I remembered that. But what I was fascinated by is how he was haunted by what happened. Harry Haft is dealing with his past, not only having survived, but to really be a survivor, to move on with your life, to get on, and to be able to deal with it. Now, of course, we refer to it as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). When something horrific happens and it ends, it doesn’t mean that now life just goes back to normal. Many people, soldiers that have fought in wars, other people who have had incredibly traumatic experiences, can’t necessarily leave it in the past. That, in a sense, is what got me to think about this and doing this project.

Ben, when you read the script, did you feel an immediate connection to Harry, or was he someone that you felt you needed to go on an exploration to find?

FOSTER: I was so glad that Barry had reached out. It was such a treat. And similar to Barry, I don’t tend to read when I’m working, and I was working at the time. But when Barry calls, you read it that day. To answer your question or to try to answer your question, it was all exploration. It was all discovery. I felt immediately, profoundly moved by the story, and the challenge of bringing a credibility to this man was an immense challenge and an honor. It was all about going down the rabbit hole.

Actors often talk about being attracted to roles that scare them. Was this one of those roles? If so, how do you deal with that? How do you get past that, in order to actually take on the performance?

FOSTER: I get frightened when I don’t know what I’m serving. I find that it gets screwy for me, if I don’t quite understand what the character is for or what the film is serving. This was so clear, though we could say morally ambiguous and living in the gray of the violence that this man went through. But I wasn’t so much afraid of it, as I felt an immense need to serve it, and then I can put me away. I can get rid of Ben for a while, and I can just investigate Harry. That’s the drug of the job.

The two of you first worked together more than 20 years ago on Liberty Heights. How did the experiences compare? What was your first experience together like? What do you remember about working with each other then, and how did this compare to that?

LEVINSON: It’s a good question. He was 16 or 17, at the time. That was a film that has a fair amount of humor in it. Twenty years later, it’s a much darker character and a more complicated role, ultimately, to play. The joy of being reunited is to see Ben, as this young kid in his first feature, and then to see him 20 years later, as this rather accomplished actor in an extremely dramatic part. It was night and day, completely different. When you see that, and you go, “My God, look at this journey that this actor has gone on, over the years, and he’s challenged himself with all these roles. And now, we’re working together again, with an incredibly complicated character.” It was complicated, in many ways, but certainly physically, as well. You’ve gotta be able to deliver on the scenes, but the physicality of what he had to go through in order to do this was pretty overwhelming.

Ben, what was it like for you to be directed by Barry in both instances? Did you even stop to think about what it was like to be directed by someone when you were a kid? How much did the two experiences affect you?

FOSTER: Immensely. We had VHS tapes and my parents’ favorite movie is Diner. That’s like, “No pressure, kid.’ I’m part of the Baltimore series now. I was very aware of who Barry was and his filmography, and I was incredibly intimidated and desperately wanted to do my darndest on set. Barry has this way of making it the least anxious set. It’s very alive. He’s got one of the most refined bullshit meters on the planet. He’s constantly hunting, what more could be added to the scene? He shaped me on our first film. The way that I approach every set has a bit of Barry with me. I think about, what else could it be? We’re constantly kicking the tires, and that’s a joy. Not everybody likes to collaborate that way. Barry’s like a jazz conductor. He’s just feeling his way through with his collaborators. It was actually a very fun set, for such dark material.

Barry, you’ve been directing for over 40 years now. What got you excited about a project in the earliest days of your career, and do you still look for the same things now, or does it feel like your criteria has changed?

LEVINSON: I don’t know that it’s changed. I worked with Mel Brooks on full-out comedies, and we were having lunch one day, and he was talking to me – and I would refer to the Diner guys and tell little stories about things – and he said, “You should write that.” I said, “Well, I don’t know how to write it.” He’d bring it up on occasion, and at a certain point, I thought, “Well, maybe I’ll try to write it.” And then, I ended up writing it rather quickly, and I thought immediately, “I ought to just direct this. I wanna direct this piece.” And fortunately, I was able to make it.

I studied with an acting group for two years. I was there almost every day for two years. I didn’t wanna act. I had no interest in acting. People would say to me, “Why are you with an acting group?” And I said, “I don’t know.” I had no idea. I didn’t know why. It was a mystery to me, but I was fascinated by it. And then, in the acting things we would do, you’d sometimes start to play around with things and go, “Hey, that’s sort of interesting.” And then, I took the idea that everything that you write should sound made up. That’s the thing that stayed with me.

So, when I wrote Diner, I wrote it as if it’s all made up. If a scene and a line is constructed with too much accuracy at times, it’s wrong. And then, when I began to direct, I applied that and went, “Well, then what else happens? What else can we do.” It wasn’t like, “Let’s do an improvisational scene.” It’s more, “Maybe there’s another thing here. What about this? Let’s forget about this, and let’s see where this will take us.” That’s the only thing I’ve gone by. Sometimes something seems good, but I wonder if it’s interesting enough. And then, if you’ve got the right actors, new things can show themselves. Some things are really important, and other things you go, “That’s okay, but it’s not worth the exploration of that.”

In your career as a director, which of your films changed the most in the editing room and why?

LEVINSON: That’s a hard question. With Rain Man, the whole thing changed a lot. It was when the writers’ strike happened. We were filming, and a director isn’t allowed to write. There was a lot of, “Why don’t we do this? Let’s try that.” That became part of the film, but they were just ideas to throw out and see what happened because we weren’t allowed to have the writer involved. We were there, so what were we gonna do? So, we kept playing around with things, just trying to get through the day, and things kept happening.

As we went along, you learn things. Dustin [Hoffman] would mention something, and then Tom [Cruise] would mention something. Sometimes we’d say, “Let’s play with that. Let’s see where that goes. What happens, if we do this?” It was a very freeing environment, in that particular case. You can’t make up a movie and improvise a film, but you can play with moments. There are things in [The Survivor] where I would mention something to Ben, or I’d say something to another actor, and then Ben would react accordingly. You start to play around with it, just trying to fulfill the character as much as you possibly can.

Ben, I think the work you do is terrific. The characters that you play, in general, and really this whole film is so transformational. It’s really impossible to define your career, the roles you play, and what you do. When you look at projects, what do you go by? Is it just an instinct when you’re reading things? Is it getting a script from someone like Barry Levinson? What makes you decide to do something?

FOSTER: I had to wait 20 years to get the call from Barry. I’ve gotta do something in between. It’s what crosses your desk. Often, it’s gotta be the filmmaker or a cast member. You hope you that you get both and that you wanna work with both. You hope that you like the character and feel that it’s something that you can add to. The word, I suppose, is serve. I think about that word a lot. How can I serve this film? When I know how to serve it, then I don’t have to think about it. Then, I can just fight for it and defend it. I feel that that’s when the best work can occur. It was very easy to feel in service of Harry. This story feels like it needs telling right now.

How was it to do the flashback scenes in the concentration camp? Those days must have had a different feeling to them. How did you handle all of that? Ben, did you hae a way that you needed to feel in those moments? How did that work with the two of you guys?

FOSTER: When I walked on set, it was very easy to fall into the nightmare. They built a 360-degree set, and it was populated with SS officers and dogs and human beings in cages. At the weight deficit that I was in, I won’t say that it was easy because it wasn’t easy, but it was easy to fall into the nightmare. You didn’t have to work so hard. It was very effective to be in.

Barry, what was it like for you to direct those moments? Are those moments that you try to approach more as an observer? Did you communicate with the actors a lot during those moments?

LEVINSON: You have a large set with a lot of extras, but you also have two characters facing one another, and you have to focus on Harry and what he’s thinking. It’s not just a boxing match. It’s not about, who’s going to win, and that’s the end of it. It’s about what he’s going through while he’s boxing. He’s not a trained boxer, but it is a fight for survival. That’s what you wanna keep in the back of your head. This is not the normal boxing film. There’s a total emotional connection to someone, to live or to die. What does that represent? What are you, when you’re fighting for your life, time and again, over and over again? It’s not a fight just to win. It’s a fight to survive. That sets up everything that takes place. He did survive, but in the world that he’s now in, how do you survive, so that you can put the past behind you and deal with life and all of the things that take place on an ordinary basis. You’ve gotta be able to suddenly live and laugh and enjoy, and all the things that are part of living. That’s the struggle of Harry Haft, to finally find that and to be able to free himself.

The relationship between Harry and his son is so interesting because the son doesn’t know his father’s history. He doesn’t know anything about what’s gone on. He just wants love from his father, who isn’t sure how to give that. Watching the two of them together is heartbreaking and beautiful, as Harry finds a way to connect with his son. Ben, what was that like, working with that young actor?

FOSTER: I’m a parent myself, and I can’t relate by saying that I was in a concentration camp. There are certain things that you wanna protect your child from in the world. You wanna keep them safe. Perhaps there are elements in yourself that you don’t want them to recognize. We had Alan Haft join us on set. We just have to remember that there are not many survivors from the concentration camp still with us. Their children experience trauma in a different way, and it felt very important to not take an easy way out. It’s not easy being a kid. It’s not easy being a parent. And allowing that difficulty to inform the scenes felt like the only way through them.

LEVINSON: For the children of survivors, there are many, many stories about how difficult those relationships are because you’re trying to shield your son or your daughter from the horrors that you faced, but at the same time, they think something is wrong. They relate it to, “Maybe you don’t like me. You don’t share things with me.” The child – the boy or the girl – wants something, and when they don’t get that connection, they just assume it’s them and that maybe they didn’t do something right. That creeps into to the equation.

Ben, what is next for you? Are you already campaigning to do Barry’s next film?

FOSTER: I’m waiting for Barry to call again. I’m sitting here, smiling and waiting. The next picture that’ll be out, I believe later this year, is called Emancipation, and that’s with Will Smith and (director) Antoine Fuqua. It’s interesting and relates to this film because that film following a man who’s escaping our concentration camps in America during the Civil War. It’s a labor camp, and I’m running a labor camp and go hunting him. It’s based on the true story of Whipped Peter. In many ways, it’s a reverse narrative for myself to explore what it means to survive. It was impossible for me to be on set in Louisiana, looking at these plantation and work sites, and not recall the Holocaust and the concentration camps that we visited, Barry and I, before filming. It’s quite jarring, actually, to see the similarities.

The Survivor can be viewed on HBO and HBO Max.