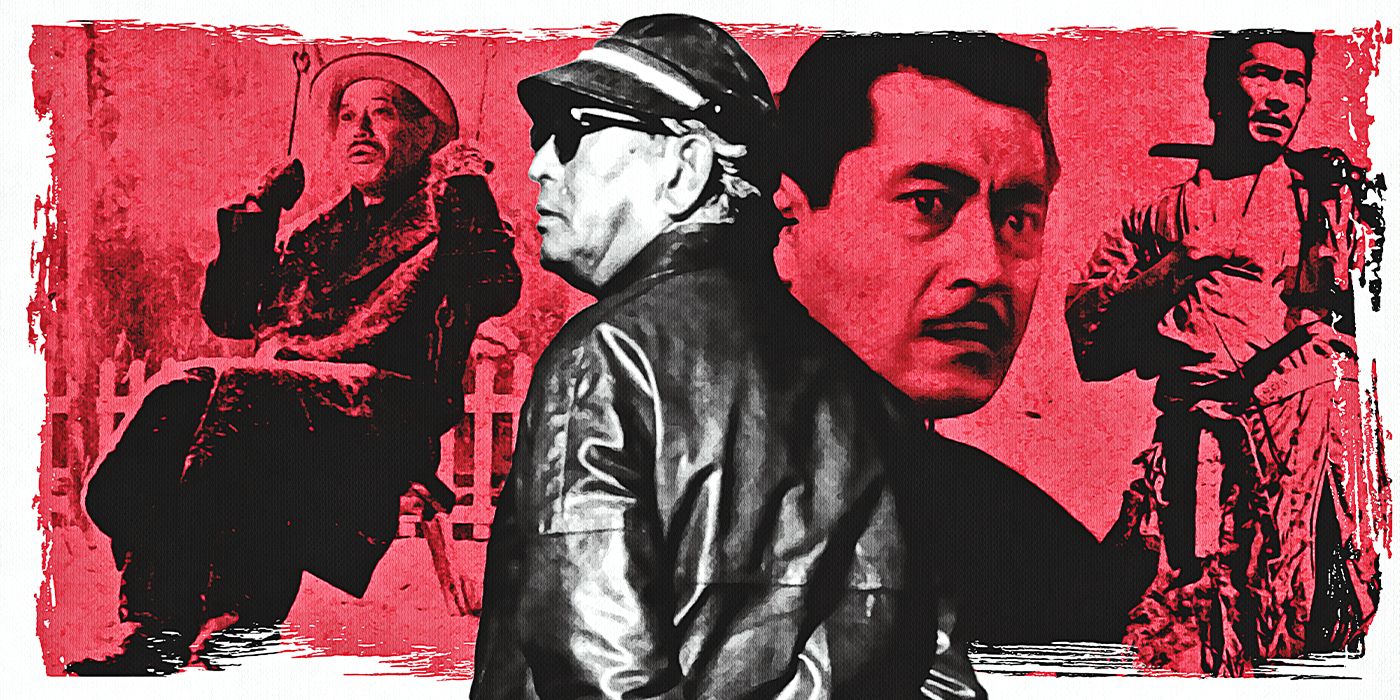

To call Akira Kurosawa a legend would be a massive understatement. In a career spanning the better part of a century, the Japanese writer and director charted a course that would range from humble propaganda films to grand period dramas and everything in between. In the process, Kurosawa would transform world cinema, combining elements of Eastern and Western filmmaking into a brilliant new synthesis that would redefine both.

With a resume as long as Kurosawa’s, it can be hard for new fans to know where to begin. The short answer, of course, is to begin anywhere – you can’t go wrong. But if you’re looking for a place to start, here are five essential films to introduce you to this cinematic giant.

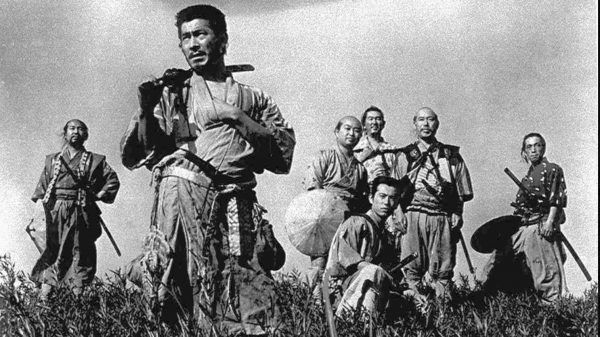

Seven Samurai

Seven Samurai isn’t just a great introduction to Kurosawa, it’s a must-watch for anyone who loves movies. The most famous of Kurosawa’s jidaigeki, or period dramas set in feudal Japan, Seven Samurai follows the exploits of seven wandering rōnin — masterless samurai who live on the edges of society as swords-for-hire — as they struggle to protect a defenseless village from a group of marauding bandits.

Seven Samurai proved hugely influential in the West, largely because it incorporated elements of the popular Western genre in its depiction of sixteenth-century Japan (bandits, outlaws, frontier towns on the brink), but also because it expanded that genre into something completely new – and in the process, helped invented the modern Hollywood action movie.

If you start anywhere with Kurosawa, start here. You’ll quickly learn what all the fuss is about.

Yojimbo

Starring Kurosawa regular Toshiro Mifune as "Kuwabatake Sanjuro,” a wise-cracking, world-weary samurai who finds himself in a small village under siege by criminal gangs, Yojimbo was both inspired by American Westerns and established many of the iconic tropes that would later become staples of the genre (largely via Sergio Leone’s uncredited 1964 remake, A Fistful of Dollars): the lawless town, the laconic, mysterious anti-hero, the shifting loyalties everywhere.

Yojimbo is fun, often funny, and also features the best soundtrack of any Kurosawa film. But in its tale of salvation through violence and deceit — of achieving virtue through unvirtuous means — it also owes some of its moral murkiness to film noir. The village which Sanjuro stumbles across isn’t a place for decent people, hence its savior will need to be someone less-than-decent, or at the very least, someone who appears to be.

Sanjuro is just the man for the job, of course, and he navigates the moral haziness of the wretched little village with incomparable style. Indeed, he only stumbles when he makes the mistake of performing a truly compassionate act, an error that would surely condemn him – were it not for the three feet of steel at his hip.

Throne of Blood

A loose adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Throne of Blood transplants the bard’s masterpiece from Scotland to ancient Japan, where Mifune steps into the role of Washizu Taketoki, the striving would-be king who is either doomed by fate or “murdered by ambition,” depending on your point of view. Partially filmed on Mt. Fuji, Throne of Blood showcases Kurosawa’s expert use of nature, not just as atmosphere, but as a character itself: winds whistle over dark soil, the rain pours through sunlit trees, and dense fog never seems to lift – reminders of grand forces untamed by, and unconcerned with, human beings.

Such elemental powers are everywhere in Throne of Blood, coolly spinning the web of our destinies, and leaving us powerless to change them. Taketoki, like his literary predecessor, cannot abide this loss of control, and he soon learns the price of such defiance in the form of a dark truth: a future foretold is not a future escaped, and the more we struggle, the more tangled the net becomes.

Ikiru

Perhaps Kurosawa’s most affecting film, Ikiru (To Live) is an acidic indictment of inept bureaucracy (a common theme in Kurosawa’s works), a tale of the bittersweet trials of parenthood, and an exploration of familial and occupational sacrifice (and how often it goes unappreciated or ignored) to name just a few. But at its core, Ikiru is about life and death — about what it means to have lived, and to have lived well, and about what it means to die with some measure of grace. Starring the great Takashi Shimura as Kanji Watanabe, an aged bureaucrat who learns that he has less than a year to live, Ikiru follows Watanabe’s struggle to come to terms not just with his impending death, but with the self-imposed emptiness of his long life.

Desperate to reclaim as much of his squandered existence as he can in his remaining months, Watanabe indulges in vice, flirts with dissolution, and chases after a young girl. It’s all too late, of course. But solace does find Watanabe, and via a surprising route: a simple, solid act of civic virtue. To say more would spoil Kurosawa's brilliant film, but suffice it to say, by the time you get to that scene, where Watanabe sings "Gondola No Uta" in the falling snow, you’ll be as changed as he is.

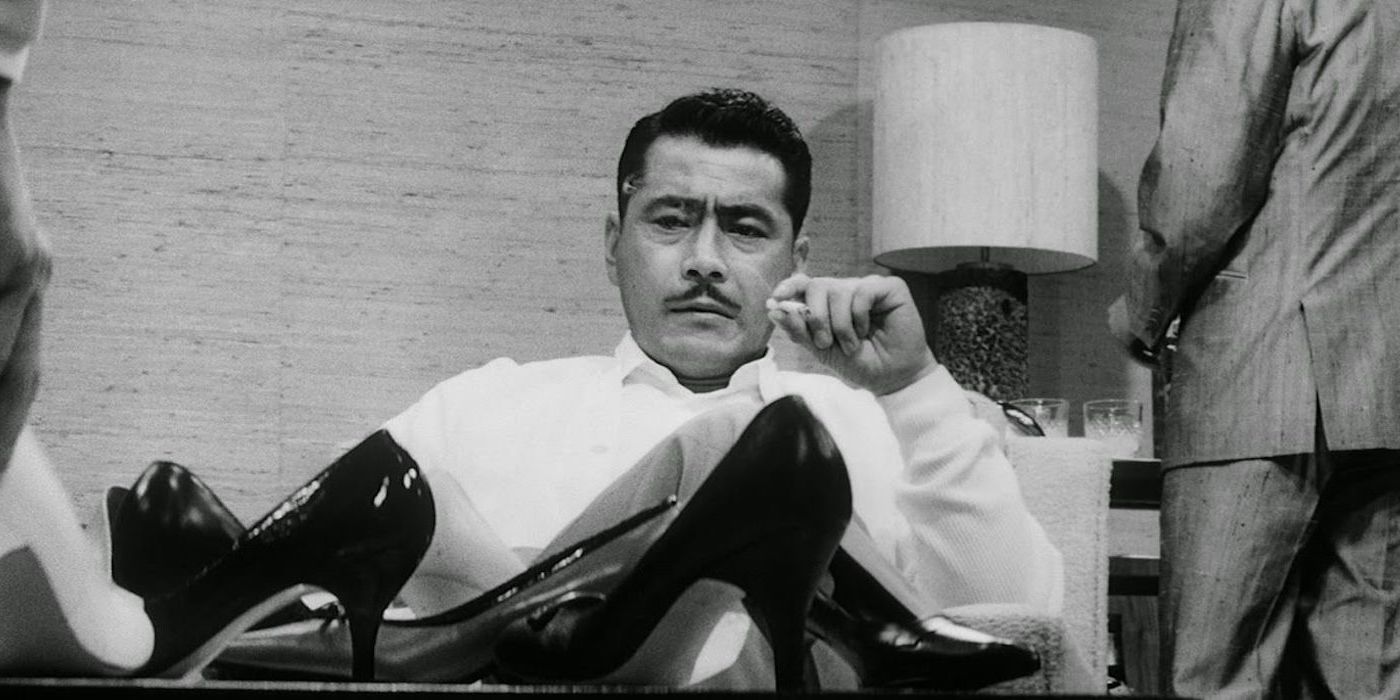

High and Low

High and Low, an adaptation of American novelist Ed McBain’s "King’s Ransom," features another preoccupation of Kurosawa’s films: the corruption brought on by money, power, and prestige. Mifune again stars as Kingo Gondo, a wealthy businessman who, believing his son has been kidnapped, must pay a ransom that will spell both his immediate financial ruin and the end of his career. But when it’s discovered that the kidnapper has mistaken Gondo’s son for another child, the tone shifts from a clear-cut personal crisis to a thorny moral question: what is the price of a human life?

The tone shifts even more from there, moving from stage play to police procedural, but Kurosawa’s indictment of modern society persists, as does his sense of tragic ambiguity. right up until the final scene, a surprisingly heartrending moment that almost pleads for a resolution, and finds only silence.