Sometimes, the best way to resolve a movie is not to resolve it at all. Audiences anticipate clarity and closure from their movies; when questions are raised, they expect most of them to be answered by the time the credits roll. However, when a movie ties up every single loose end, it can give the impression that they don’t trust the viewer to draw their own conclusions. It’s exciting, then, when a movie leaves questions unanswered, when it ends not with a period but with a tantalizing ellipsis. When it’s done poorly, it can be insultingly lazy (remember when The Devil Inside abruptly ended and told the audience to look up the ending online?). When it’s done right, it’s unforgettable. (See Inception, The Shining, The Green Knight and more examples of what works below.)

Here are 11 of the most haunting, thrilling, thought-provoking ambiguous endings in film.

The Graduate (1967)

At first, it might seem as though The Graduate takes a turn for the fanciful at the end. After spending much of its runtime as a grounded romantic dramedy about aimless post-college ennui, The Graduate’s climactic scene features Ben Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) interrupting the wedding of his lover Elaine (Katharine Brown) right in the nick of time. It could have come across as contrived and silly, no matter how passionately they screamed each other’s names through the sanctuary glass. But the love story isn’t tied up in a romantic bow. As the exhilarated lovers sit side by side in the back of a bus bound for the future, the adrenaline starts to wear off, and their smiles begin to fade. They look down; they shift uneasily; they glance at each other for reassurance. The unspoken question hangs in the air: what now? It’s the perfect ending for an era-defining movie about a generation heading into an uncertain future.

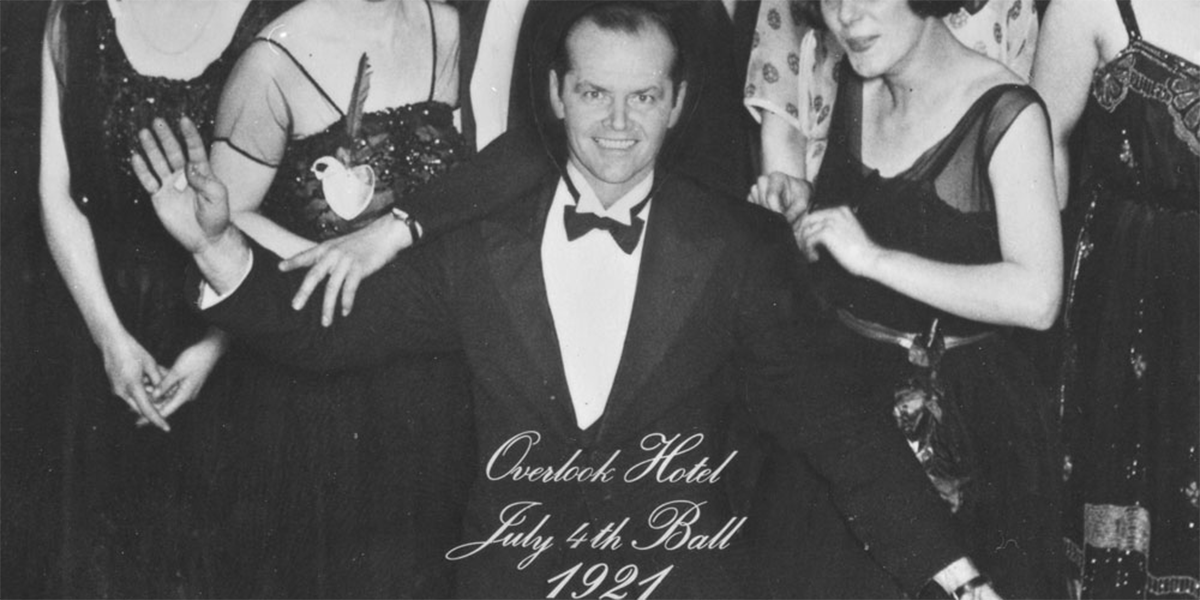

The Shining (1980)

2001: A Space Odyssey may have one of the most infamously surreal endings in film history, but it isn’t exactly ambiguous; it’s just strange and unexpected. When Stanley Kubrick adapted The Shining, another novel by a seminal author of genre fiction, he made things even less straightforward. The entire movie is ambiguous, to the point where there’s an entire documentary devoted to figuring the damn thing out. But all that geometric carpet and depraved bear-suit sex would be for naught if the ending didn’t work; thankfully, it’s one of the best ever. There are various theories as to why Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) was photographed at the Overlook Hotel years before he was born: reincarnation, spirit absorption, a dying hallucination. But quotidian video essays and explainers can’t take away the eerie power of that slow zoom-in on a wall of old photos, “Midnight, the Stars and You” echoing through the empty hotel.

Blade Runner (1982)

The original theatrical release of Blade Runner did not have an ambiguous ending. Thanks to meddling executives, it had a clumsy, incongruously sunny ending that’s barely worth talking about. When people talk about Blade Runner, they’re talking about either the Director’s Cut or the Final Cut, both of which have endings that are more ambiguous, and consequently more effective. After the climactic confrontation with Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), soon-to-be-former Replicant hunter Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) returns to his apartment, where his Replicant lover Rachael (Sean Young) is sleeping. There, he finds an origami unicorn, left by Gaff (Edward James Olmos), his enigmatic partner, who is strongly implied to know the truth about Rachael. But the only appearance of unicorns thus far was in Deckard’s dreams. How does Gaff know that? Is Deckard a Replicant? Is he subject to the same “expiration date” as Rachael? The answer follows Deckard and Rachael out the door, and into the unknown.

Pink Floyd – The Wall (1982)

The Wall is an exhausting movie. Based on Pink Floyd’s rock opera of the same name, it’s an unceasing onslaught of dystopian imagery, nightmarish animation, and Roger Waters’ own trauma from his upbringing in post-war Britain. But while The Wall has been accused of lacking subtlety, its heaviness makes the ending that much more impactful. After the destruction of the titular Wall, children walk into the rubble and begin to clean up. An elegiac brass band plays as these children step through broken glass and pile bricks into toy trucks. The final shot is a freeze-frame of a boy pouring out an unused Molotov cocktail. It’s The Wall’s quietest moment, and it expresses something like hope. But the Blitz parallels are clear; coming at the end of a film that deals with the ugly scars World War II left on British society. It’s possible that those children will be cleaning up for a long, long time, only to build a new Wall. “Isn’t this where we came in?”

American Psycho (2000)

There are two different ways to interpret the ending of American Psycho, both of them horrifying. Wall Street yuppie/gruesome serial killer Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) tearfully confesses to his lawyer that he murdered scores of people, including his co-worker Paul Allen, whose apartment he uses to hide bodies. But the next day, the bloody apartment is spotless and being sold by a realtor, and Bateman’s lawyer says that he had dinner with Allen in London a few days before. Therefore, Bateman is either a delusional man with violent fantasies who isn’t getting the help he needs, or he’s a genuine serial killer who will never get caught because the people around him are so self-absorbed they literally can’t tell their friends apart. Either way, he’s back in a soulless trendy restaurant, stewing in self-hatred, a sign above a door reinforcing his private hell: this is not an exit.

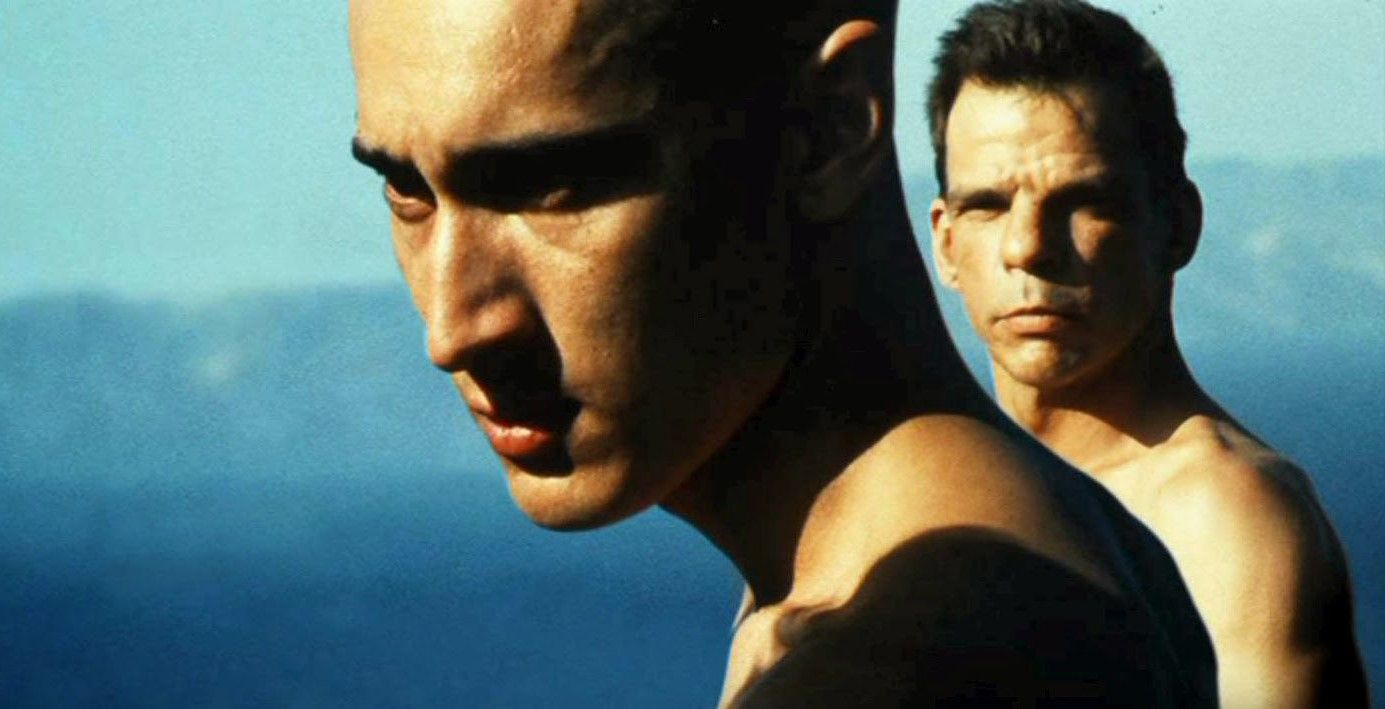

Beau Travail (1999)

A broken man, Galoup (Denis Lavant), narrates the events of Beau Travail from the present day in Marseilles. A former assistant commander in the French Foreign Legion, he became consumed with envy and resentment toward a handsome legionnaire named Sentain (Grégoire Colin), eventually stranding him in the East African desert to die. (Sentain is saved by a nomadic tribe, but no one in the Legion knows that.) Court martialed and banished from the one thing that gave his life meaning, Galoup makes his bed and lies down with a pistol. His arm muscle twitches, he prepares to shoot…and then, suddenly, dance. Back in a Djibouti nightclub he used to frequent, Galoup dances to Corona’s gloriously cheesy Eurohouse hit, “The Rhythm of the Night.” At first, he’s stiff and tentative, faintly embarrassed; by the end, however, he’s leaping in the air, flailing his arms and thrashing on the floor with cathartic abandon. Is it a dying vision? A happy memory? Or did Galoup live on after all? No matter what happened, Galoup’s ecstatic dance suggests that he’s finally free.

Inception (2010)

So much depends upon a little blue top spinning on a wooden table. By the end of Inception, dream infiltrator Dom Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) has been through so many layers of reality and unreality that he’s not sure if he’s still in a dream or not. And so, when he returns home, he uses his late wife’s “totem,” or an item on one’s person that behaves differently in a dream. If the top falls over, it’s reality; if it spins indefinitely, it’s a dream. But when Cobb sees his children again, he goes over to greet them at long last, leaving the forgotten top to spin, slightly wobble — and then, cut to black. Christopher Nolan obsessives have theorized and argued over whether it was a dream or not, supporting their claims with evidence: Dom’s wedding band, or the presence of Michael Caine. But to fixate on the top misses the point; Dom certainly doesn’t care either way. The lack of closure is itself a form of closure.

A Serious Man (2009)

Why do bad things happen to good people? A Serious Man answers this question, in typical Coen brothers fashion, with a hearty “hell if I know.” An adaptation of the Bible's Book of Job, A Serious Man centers on one Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg), a Jewish professor in the 1960s whose quiet life in suburban Minnesota is upended by one gut punch after another. He’s blackmailed by a student, his wife wants a divorce, anonymous letters are being sent to deny him tenure — and it gets worse. It’s unclear if this is merely bad luck or part of some greater design, and the ending only complicates matters. Right when it seems things are looking up — he makes up with his wife, and may get tenure after all — Larry changes his blackmailer’s grade and immediately gets an urgent call from his doctor about his latest chest X-ray. Meanwhile, his son is struggling to get into an emergency shelter as a huge tornado approaches his school. Cruel fate, divine punishment, or false alarms? Well, who can say?

Birdman (2014)

Birdman is the story of a washed-up actor overshadowed by his past role as a superhero, losing his mind as he desperately tries to be taken seriously. Or perhaps Birdman is about the triumph of Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton), who achieves greatness, respect, and maybe something like immortality through his work. It all depends on how one interprets the movie, and particularly its ending. How much of what happens is real? Did Riggan actually shoot himself on stage at the end of his play? Is the rapturous praise he received afterwards real, or a dying dream? What about the manifestation of his past self in his Birdman costume? Is he real, and if he is, is he friend or foe? And of course, what does one make of that climb out the hospital window, and his daughter’s awestruck gaze towards the sky? Maybe, as Birdman’s subtitle suggests, there’s an unexpected virtue in not knowing.

The Lobster (2015)

The Lobster takes place in a world of absurd absolutism. Every adult must find a life partner, they must share at least one superficial trait, and if they can’t find a partner after 45 days at a hotel retreat they must transform into an animal of their choosing. Binaries abound, from morality down to sexuality; when David (Colin Farrell) asks if he can register as bisexual, he is flatly told that this is not an option. (He registers as heterosexual, but he has to think about it.) To end a story about such rigid, black-and-white thinking with an ambiguous ending is exactly the kind of sly touch one should expect from Yorgos Lanthimos. After a long ordeal at the hotel, followed by time in a rebellious loner community that’s just as toxic, David is on a date with his last chance at a life partner, a blind woman (Rachel Weisz). In the restaurant bathroom, David steels his nerves, preparing to blind himself with a steak knife…and the movie ends on the blind woman, waiting patiently. It’s as unnerving as it is thrilling.

The Green Knight (2021)

Per the rules of a complicated Christmas game, Sir Gawain (Dev Patel) must journey to the chapel of the Green Knight (Ralph Ineson) in order to get his head chopped off. Protected by a girdle that supposedly offers invulnerability, Gawain nonetheless loses his nerve, returning to Camelot in shame. While he succeeds King Arthur, he becomes a loathed figure, losing the love of his life and his son in the process. With the enemy at the gates and no way out, Gawain undoes his girdle at long last, letting his head fall off…only to end up back in the chapel, having seen a vision of a possible future. Finally, he takes off his girdle and bravely offers his head, which seems to please the Green Knight. He gently draws his finger across Gawain’s throat and warmly says “now, off with your head.” Is he making Gawain’s death easier, or is he playfully letting him go? Either way, the film implies, Gawain lives on.

.jpg)