The appeal of the director's cut burns inside the mind of every cinephile. We all want to see that pure, unfiltered vision of a filmmaker, especially if the new cut is for a film with known production troubles. If the theatrical version is a film we already like, we want to see more of it. On some level, that vision is what art is all about -- getting to experience a story through another person's mind for a period of time. However, director's cuts can also prove to be a real detriment to the film. Filmmakers can overthink their decisions and produce something more muddled, including scenes they rightfully cut the first time, or they can lose the spirit of collaboration that often helps many filmmakers in making a movie people enjoy. And sometimes, if the filmmaker has enough power, they can strike the original version from the record, making only their new cut available. (We're looking at you, George Lucas.)

When a director's cut does improve the original film, a wave of relief can wash over the audience. That nugget of gold they suspected might be there finally reveals itself, whether it makes a bad film good or a great one a masterpiece. These seven films show how transformative a new director's cut can be on its original film, and in a few cases, they completely restore and revitalize the films' reputations critically and in popular culture.

Apocalypse Now

Francis Ford Coppola is no stranger to the director's cut. In the last few years, he has recut The Cotton Club and The Godfather Part III, both films seen as disappointments on their original releases, and revitalized them into fresh, exciting films. While it's understandable to want to try again with a film that was perceived as a failure, Coppola has also spent a long time tinkering with Apocalypse Now, a film that had an extremely troubled production but is also widely seen as a masterpiece and one of the finest war films ever made. His first crack at a director's cut was in 2001 with Apocalypse Now Redux, a cut that added a whopping 49 minutes of new material to bring the running time to well over three hours. Redux was a case of subtraction by addition, flattening out the drama and slowing the film's pace to a crawl. One sequence in particular, featuring a detour at a French-run plantation, brought the film to a screeching halt. In 2019, Coppola debuted Apocalypse Now Final Cut, which removed 20 minutes from the Redux version. Through this tightening, it was finally easy to see how Coppola felt that these sequences he added back in were necessary for the film's texture and sense of otherworldly mystery. They just needed to be trimmed up a bit. The original, theatrical version still plays like a masterpiece, but the Final Cut adds a ton of worthwhile color that would now feel missed.

Blade Runner

Arguably, Blade Runner stands as the poster child for how a director's cut can totally reinvent a movie. The theatrical cut for Ridley Scott's science-fiction noir infamously featured voiceover by Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) that neither Scott or Ford wanted to use. (Ford sounds audibly resentful for having to record it.) And Scott was forced to shoot a happy ending for the film, which featured unused driving footage from The Shining. Ironically, the 1992 Director's Cut of Blade Runner was not really a director's cut, as Scott only provided notes while film preservationist Michael Arick was in charge of putting it together. It wasn't until the 2007 Final Cut that Scott had total control over. That one is easily the best version, removing the voiceover and the happy ending while adding Deckard's unicorn dream and the violent action cuts used in the international version of the film. The Final Cut turned Blade Runner into the bleak noir it had always needed to be and is now seen as an essential sci-fi text.

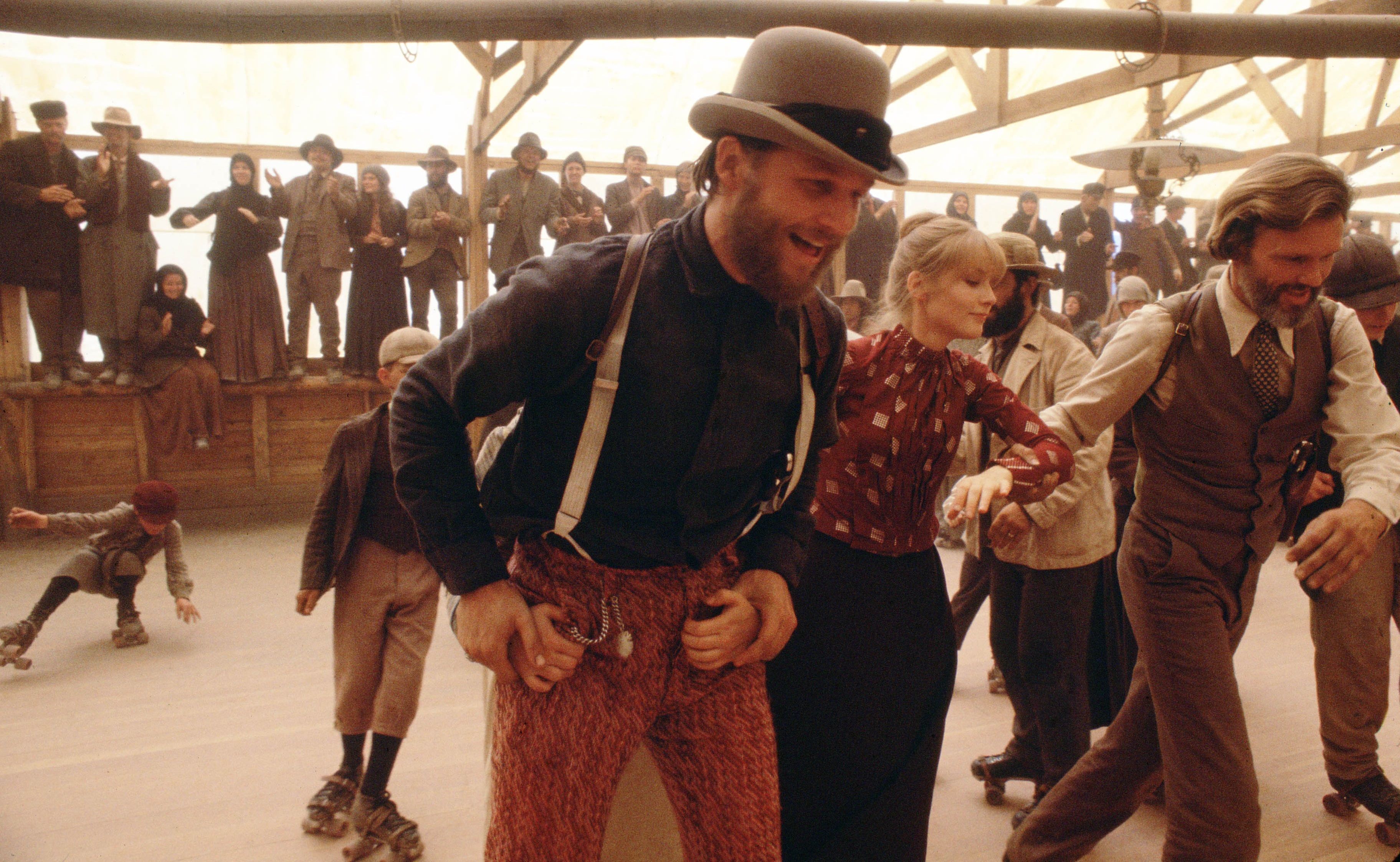

Heaven's Gate

To say that Michael Cimino's Heaven's Gate was a flop would be a massive understatement. Coming off of winning Best Picture and Best Director for The Deer Hunter, Cimino was given a massive budget of $44 million (about $168 million today) to make a Western epic where production was completely out of control. Cimino was reportedly an obsessive nightmare on set. In their book, Movie Idols, John Wrathall and Mick Molloy wrote, "At one point during filming, [Cimino] decided that the spacing of the buildings on one of the sets didn't look right, despite it having been built to his exact specifications. He ordered both sides of the street torn down and rebuilt at a cost of $1.2 million." In post-production, the studio wanted to fire him every step of the way. The negative press surrounding the insane production, as well as the many accusations of animal cruelty on set, helped Heaven's Gate gross a miniscule $3.5 million at the box office. Things were going so bad that they pulled the film from theaters a week after its initial release to recut the film and try to salvage it. Various cuts have been done over the years, but it was not until 2012 that Cimino finally got to release the version he was most happy with. Running 216 minutes, the director's cut of Heaven's Gate shows little sign of a production in disarray and instead plays as a grand, beautiful epic that feels right in line with The Deer Hunter. The animal cruelty is still there and hard to watch, and no one would blame you for skipping out on it for that reason. But if you can stomach it, you will see the kind of large scale filmmaking no one gets to even attempt anymore.

Ishtar

While the first three films on this list had directors looking to add a lot of material or radically reinvent the work, Ishtar, from writer/director Elaine May, does something completely different. All the 2013 director's cut of Ishtar does is remove two minutes from the theatrical version. It's essentially the exact same movie, just a tiny bit tighter. The cuts mainly consist of a few jokes May found to be culturally insensitive after a couple decades of reflection. Like all these films, Ishtar was an infamously troubled production that went overbudget and saw May in a constant battle with star Warren Beatty, who likes to take a lot of authorial control over the films he works on. When the movie was first released, many of the reviews were analyzing the tabloid fodder of the production rather than the film itself. As it turns out, the buddy comedy starring Beatty and Dustin Hoffman as a couple of terrible singer songwriters unknowingly caught in a plot to overthrow the Emir of Ishtar is truly a delight, packed with outrageously funny gags and songs by Paul Williams that ride that perfect line of terrible and hilarious. No, Ishtar is not the most revelatory director's cut, but it is one of the few director's cuts where achieving that "original vision" is not the goal. Instead, May makes a cut to keep up with the times, helping the comedy age better than a lot of other comedies do.

Little Shop of Horrors

Sometimes test audiences don't know what they are talking about. The original ending of Little Shop of Horrors, adapted from the Off-Broadway musical by Howard Ashman and Alan Menken, had the man-eating plant Audrey II devouring the show's lead characters and eventually taking over the world. When Frank Oz showed the film with this original ending, which featured an absurd amount of impressive visual effects showing these giant plants take over cities and finally rip through the screen as if they were coming after us, test audiences revolted. They liked the two leads, played by Rick Moranis and Ellen Greene, too much and were angry they had been eaten and killed. Oz shot a new ending where Moranis' Seymour saves Greene's Audrey from death, and they kill the plant. Sure, that is nice and tidy, but it completely guts the entire thematic point of the piece, where greed will eventually devour us all. Luckily in 2012, the original ending was reinstated into the film, and now Little Shop of Horrors can exist as it had always been intended.

Once Upon a Time in America

Studios are often scared of long films. For one, the longer a film is the less often they are able to show it in a day, but also, if they feel like they don't have a hit on their hands, they will slash the film to pieces in order to make it run faster. Such was the case with Once Upon a Time in America, the final film by Italian director Sergio Leone. After receiving a rapturous response at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, it already received a few cuts in order to receive an R rating in the United States. After receiving less than great reviews from the American press, the studio removed about 90 more minutes from the film and rearranged the timeline into a chronological story, which led to Leone disowning the film. Since then, it has been a battle to try and restore Once Upon a Time in America to its full 269-minute running time. The closest we have gotten was when Martin Scorsese and the Film Foundation were able to put together a 251-minute version, which does play like one of the great gangster films of all time. Those remaining 18 minutes are tied up in rights issues, and a decade after the 251-minute release, there is still no word on the status of those scenes. In a sense, we still have not gotten the director's cut of Once Upon a Time in America, but the restored version we do have is pretty close.

Touch of Evil

Aside from his first film Citizen Kane, Orson Welles never had an easy time making a movie. The studio removed 40 minutes and reshot the ending of his sophomore feature The Magnificent Ambersons. In his late career, he would have to spend years making movies because he could only scrape together enough money to shoot things in fits and starts. Touch of Evil, the 1958 film noir classic, was another film taken away from Welles in post production, which saw a lot of footage cut, reshoots done with a different director, and a new score implemented. In response to what the studio had done to his film, Welles wrote a 58-page memo detailing every change that needed to be made in order for the film to work. Of course, the studio did not adhere to this and released their cut. While the deleted footage of The Magnificent Ambersons was destroyed, luckily in 1998, renowned editor Walter Murch was able to use Welles's memo and reconstruct Touch of Evil into the film he had outlined. While this may stretch the definition of "director's cut," since the director was not present for its assembly (because, well, he was dead), every alteration was made based off his original suggestions. Now, we have one of the rare films from Welles' time in Hollywood where it feels like it was purely his vision.

Ideally, we would live in a world where the theatrical cut of a movie would be the director's cut. Having a cohesive vision from a strong voice makes for the most engaging pieces of art. Sure, some of them may be overly indulgent, but that experience of learning how to reign yourself could prove useful to many filmmakers. These seven films demonstrate, though, how vital authorial voice is in making something that will stand the test of time. Whether a film succeeds or fails should fall on the shoulders of the creative people behind these movies and not those in the business of risk management.