The Austrian filmmaker Claude Lanzmann, who passed away in the summer of 2018 at the age of 93, once said that archival images are inherently flawed because they have no imagination and, by extension, leech the power out of movies built off these images to evoke and stir thought. In his view, the very attempt to reconstitute the experience of existing in or thoroughly retelling a historical event is an act of surrender to the preexisting framing of the past, a tactical retreat from the realities of time and the challenges of memory. To accept an image created by someone else is to also accept the narrative framing that that photographer or cinematographer is making therein and that comes with more than one moral and artistic concession.

It’s unclear if Lanzmann was fully aware of how widespread and obsessive image manipulation would become in the 2010s, but it is clear that he saw the dangers in assuming that the defining images of the past and the narratives they presented would never erode or mutate. As the Obama era gave way to the Trump years, the litigation of imagery and the practice of crafting images has become the premiere social activity, one done predominantly online but that comes with torrents of real-world effects. On Snapchat, you can give yourself big glowing eyes, add illustration, and smooth out discerning features as a representation of you. Bursts of 120 or 280 characters with photos, memes, gifs, and short video create a simulacrum of personality for the public to ignore, condemn, embrace, and celebrate on Twitter. None of this is necessarily new but the intensity and pervasiveness does seem to have increased dramatically. What exactly is the documentary, a film style largely misconstrued as tied inextricably to telling the truth, supposed to do to keep up?

The very best documentaries of the 2010s, including those that buck against Lanzmann’s conclusions, have gone about not only questioning the concrete meaning of any given image or snippet of audio but also subverting the idea that the messiness of life experienced first-hand can be summated in any honest way through traditional narratives. Ezra Edelman’s O.J. – Made in America refuses to allow either the portrait of Orenthal James Simpson as a victim or a unique monster to be perceived as sincere; he is both and so is the public. Amidst anti-Russia hysteria and unyielding demonization of left-wing or third-party candidates, Adam Curtis’s Hyper Normalisation presented a far more chilling and convincing reasoning for the rise of President Donald Trump, a theory rooted in the government and the ruling class’s need to control and reinforce an outdated, wildly inaccurate story of America and its citizens. Even documentaries constructed entirely of archival images, such as Let the Fire Burn and The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu, are revitalizing and damning in how they reframe images of the past as sloppy and gaudy presentations of faulty, half-blind narratives.

The best documentaries of the 2010s are also the most skeptical, whether or not that fact is worn on the film’s sleeve, and that is what I sought while compiling my list of the 35 best documentaries of the 2010s. In the interest of full transparency, I gave myself a few ground rules in making this list, primarily no more than two films by any given director are included and there must be proof of each film being screened on a big screen for the public at some point. This was done both to show a level of diversity in styles and perspectives and distributors, and to avoid making up half of my top ten with the work of Frederick Wiseman, still the best American filmmaker currently living and arguably the most influential documentary director to ever pick up a camera. At 89 years of age, Wiseman represents the height of the cinematic form beyond the confines of documentary as a genre or a style, even if he has no claim to innovation the way Sandi Tan’s miraculous Shirkers or Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing do. Wiseman the artist, as much as any of the films that can be found below, has come to represent a dated saying that nevertheless neatly summarizes the arc of the 2010s: what is old is new again.

35. The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu

Many discussions of Christopher Nolan’s recent Dunkirk revolve around the film’s visual power on the biggest screens imaginable, whether in 70mm prints or IMAX. It’s hard to dispute that but Nolan’s bloodless technical exercises are no match to Andrei Ujica's cumbersome assemblage of footage of the wildly corrupt former Romanian president of the title. To watch the grand exhibitions thrown in his honor, the massive echoing chambers of legislature, and even his intimate meetings with other leaders on the big screen is to at once understand the power Ceausescu wielded and witness the empty pageantry that often passes for leadership. And when the movie turns toward his grievous misdeeds and widespread use of unlawful detainment, torture, and murder, it makes his inevitable fall as a weak, exhausted old man all the more grandiose.

34. Behemoth

The title says it all in Zhao Liang’s bleak vision of modern China. Each one of the director’s images is centered largely on China’s iron mines and the workers that toil within its deadly catacombs. On the big screen, the size of the people and their equipment, as well as the noise, is overwhelming, and that’s not even getting into the factory conditions or the outcome of this deadly work. To that point, the filmmaker also visits one of China’s famous “ghost cities,” where empty high-rises built with that same iron line the streets in the hopes that investors will flock there eventually but also to keep up the reputation of President Xi Jinping. Few documentaries need to be seen on the big screen to fully understand the magnitude of the forces at work as Behemoth. Even fewer are laced with such undiluted political rage and sadness for one’s home.

33. 12 Days

The title of Raymond Depardon’s revealing 2017 feature refers to the period of time in which a French citizen must see a judge after being involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital to see whether or not they must stay there. Depardon has long made his career on catching people at their most vulnerable – his best film, Caught in the Acts, focuses on shoplifters being interrogated by company security officers – and in 12 Days, he finds a scintillating crosscut of modern French citizens making their case for their occasionally beguiling behavior. The result is a tough-minded study of governmental interference in miniature, in which the freedom to do what you wish with your life is set against a need to uphold a sense of stability in society, as well as a kind of malleable morality. Rather than overtly editorialize and diving into the argument whether liberty is more important than the safety of the everyday citizen, Depardon simply lets the people speak on their experiences in gorgeous long takes, each one of which uncovers a complex life that came to a visceral emotional climax, some convincing and others not. In doing so, the director renders miniature episodes of untamed individuals set loose and then left to explain their unique actions in an environment that has long demanded strict, rigid control, even if its just for show.

32. Approaching the Elephant

Where many documentaries have strived and failed to encapsulate the issues facing modern public education, Approaching the Elephant takes a bolder route. Director Amanda Wilder spent a year in New Jersey’s Teddy McArdle Free School, a democratic school where classes and subjects are voted on and attendance is optional. Her black-and-white footage of Alex, the head of the school, and his students reveals a fascinating experiment in education and a study of the democratic process and regulation in micro. Alex must deal with concerned parents, unruly and attention-hungry students, and the not-so-grounded structure of his distinct schooling on the fly, and Wilder’s grainy, black-and-white imagery reflects both the purity and amateurish nature of his venture. In the classrooms of the Little Falls-based school, the director brings out an unexpectedly challenging vision of freedom of choice as both a crucial and emblematic part of America and an element of democracy that allows the stubborn and under-educated to often baselessly halt progress.

31. Zero Days

Consider Alex Gibney’s latest work – one of the prolific filmmaker’s very best – as an alternate history of the Iran Nuclear deal, one in which the watchful Western eyes get poked by their own sharp stick. In this metaphor, the stick is StuxNet, a computer worm manufactured by Israel and the USA in secret to keep a leash on Iran. Things did not quite turn out that way, as Iran eventually utilized the cyber-weapon to their own advantage to give us our own national security hair-mussing. At once an engrossing, detail-oriented cyner-thriller and a brilliant primer on the era of cyber warfare, Zero Days renews and reinforces the argument that Gibney is one of the most thoughtful and direct political filmmakers out there.

30. Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World

When Werner Herzog set out to come to a better understanding about America’s relationship with the death penalty (and murder) in Into the Abyss, he viewed it in behavioral terms almost exclusively, even as his subjects poured over the details in oft-familiar true-crime-procedural fashion. Coming to the internet and the future of coding in Lo and Behold, he brandishes a similar perspective but his view is more vast here, his moral depth of field much longer. He visits with a family who lost a daughter to cyber-bullying, talks shop with Elon Musk, and visits with patients at a clinic for Internet addiction, all in the hopes of seeing how humans have come to let the Internet become part of their core being. Without making broader judgments about the dangers of the Internet, he surveys a world where an online identity can easily be perceived as more precious and appealing than the one you hold offline and catches a grim glimpse of what might come when the offline self has no perceived worth or utility to society anymore.

29. Rat Film

Theo Anthony’s essay film Rat Film constantly cuts from the denizens of Baltimore’s black neighborhoods to the film’s composer, Dan Deacon, sculpting the warbling synths that will become the score. It’s a nod not only to the self-referential style of Anthony’s film but to the heart of the matter in Rat Film: race. Deacon comes from Wham City, the famed Baltimore collective that gave rise to Deacon and noise-punk outlaws No Age, music that is at the forefront of noise rock and noise pop. And yet, not all that far away, black men spend their times getting rid of rats by literally fishing for them with cheese. In another neighborhood, a black pest controller muses about the origins of the city’s rat problem but also the hardships of making a decent living in the city without higher education and with a mark or two on your arrest record.

In mining the history of Baltimore’s rat infestation and racist city planning, including sketches and drawings of county lines and districts, Anthony is smart enough to see the privilege given to himself in being able to make this short, sensational movie, much like Deacon is allowed to make his music. It’s an important moment of personal confession, amongst a plethora of intimate experiences, remembrances, and statistics that come to outline a bleak future for Baltimore’s oft-plagued black population.

28. The Unknown Known

Could any other director other than Errol Morris get Donald Rumsfeld to talk so candidly? Can anyone make people talk the way he does? It’s a question that comes to mind in Morris’ Tabloid and Standard Operating Procedure but it’s never been more front and center than in The Unknown Known, in which Rumsfeld gives an abbreviated but no-less mesmerizing account of his life and times. There are no bombshell moments of political revelation, though his time in the President George W. Bush’s administration is the centerpiece of the film, but Morris gets a handle on something bigger: the way he thinks and expresses himself. By seeing Rumsfeld as a seasoned, evasive communicator and an unpredictable thinker first and foremost, the director finds the unexpected art and wonky philosophy of the two-time former Secretary of Defense while simultaneously condemning where his thinking and actions led us.

27. And Everything Is Going Fine

The monologist Spalding Gray seemingly took his own life in 2004, when his body was found in the East River after he reportedly jumped off the Staten Island Ferry. There is not much about his death in Steven Soderbergh’s graceful assemblage of footage of Gray from throughout his life – in movies, on stage, being interviewed on TV, etc. – but he certainly gets at his struggles with depression and disease. He allows the late artist to speak for himself and to tell the story of his life the way that he wanted it to be presented to the public. Some footage shows tracking damage while other snippets feature blown-out color and light balances, suggesting different sides of his personality as well as a brief visual history of how performance is recorded, leading all the way up to the advent of digital cameras. Professional and societal insights abound in Gray’s monologues and extended exchanges but what makes And Everything Is Going Fine so moving is the story of a man who could seemingly talk endlessly about anything until he seemingly lost the will to face himself and what was happening to him.

26. Dawson City Frozen Time

The director Bill Morrison utilized a treasure trove of footage at the Dawson City Film Fund to create this wondrous experimental documentary, Dawson City Frozen Time. The glut of the movie is made up of passages from films we will likely never seen in full, only rescued in snippets after poor storage and preservation standards led to them being essentially destroyed. Others burned up, as is the inherent danger of shooting anything on nitrate. The volatility of the format itself informs Morrison’s view of history, which he traces from the Gold Rush to the early 1930s. The filmmaker delights in plumbing the historical and geographical details of Dawson’s rise and financial downturn, strewn with a bevy of stories that lay the bedrock of Hollywood’s salad days in the 1920s, but Dawson City: Frozen Time pushes further. In assembling footage of these thought-lost movies, some by early female filmmakers, Morrison suggests an alternative history in which these people influenced early Hollywood and were discussed with similar fervor as early silent American masterpieces. He also, perhaps inadvertently, presents a striking argument for cinema being an all-too-important reflection of society and political structures that can themselves help shape and influence culture. Few movies this year felt so sensationally alluring, even hours after the movie itself finished.

25. Strong Island

The killing of William Ford Jr. in 1992 is the focal point of Yance Ford’s viscerally personal documentary Strong Island, but it’s white society’s disrespect and seeming indifference to his family’s need for closure that comes ringing out most loudly. Ford introduces the facts of the murder of her older brother early on and interweaves the studying of the crime scene, where mechanic Mark Reilly shot Ford dead after a disagreement over work done to the victim’s family vehicle. More importantly, the director follows her own search for answers that prove unsatisfactory and traces the history of not-so-subtle disrespect that plagued her parents when they made the move to Long Island. Ford even goes as far to tape his own confessions about his brother, the case, and the aftermath that shook the family unit. What emerges is a searing portrait of white ambivalence to black suffering, only mitigated by the stirring intimacy of Ford’s memories of family and self-discovery. It also happens to be the best movie Netflix has put its weight behind since 13th.

24. Hyper Normalisation

This is the first of two entries that could be construed as cheats. Adam Curtis’s haunting BBC-backed movie Hyper Normalisation never saw official stateside theatrical release outside of one-off screenings in museums and independent art spaces. It was made available on YouTube for a time, however, and in a cinematic culture that inarguably depends on streaming as a method of distribution; YouTube is no less of a legitimate platform than Netflix, Hulu, or Amazon. In hindsight, the, er, troubling streaming behemoth is also the ideal place for Curtis’s savvy and unsettling depiction of how the simple mechanics of narrative and the societal need to feign stability even in the face of total collapse fueled numerous political disasters, from the election of Donald Trump and Brexit to the War in Syria and the strengthening of Putin’s regime. Taking its name from Russian literature, Hyper Normalisation would feel culled from the deepest conspiratorial levels of YouTube’s bottomless suggested-video algorithm if it wasn’t so confidently and convincingly strung together by Curtis, who also acts as his own narrative. Three years of Trump’s reign has brought us a handful of forgettable, incoherent anti-Trump documentaries, all of which seem more interest in stoking outrage than actually tracing how we got to this point. The sobriety and alarming historical context that Curtis brings to the table is all the more bewitching and transgressive in comparison.

23. Of Men and War

There are three versions of Of Men and War floating around and I would suggest you find the longest version possible when hunting it down. The 142-minute version especially allows for a full immersion in the world of Yountville, California’s Pathway Home, a unique PTSD treatment facility that hinges on therapeutic talking between former and inactive soldiers. There’s little in the way of style in Laurent Beque-Renard’s direction but he brings a tonnage of experience covering and studying the effects of war – he reported heavily on the Bosnian War – to bear here. He captures the therapeutic discussions and meetings, the intermingling between the soldiers, and their home lives, which prove to be distinctly difficult gauntlets for many of these men. We may never see the end of our wars in the Middle East or, for that matter, movies about those myriad conflicts, but scant few will be so attentive to the direct psychological and emotional effects of serving one’s country.

22. Minding the Gap

You would be forgiven if you thought the three leads of Bing Liu’s moving debut Minding the Gap were lifelong friends who had all grown up worshipping skateboards and coming to terms with the men who molded them. They all seem naturally at home with one another, intimate without pretense and uncannily vulnerable in their admissions and denials to one another. The truth is that Liu, who serves as one of these leads, found his co-stars, Keire and Zack, while looking for subjects for his first film. With them, however, he finds common rhythms of rebellion and self-harm that becomes the padding for much talk of lives bled white by poverty, abuse, and alienation. In the film’s emotional climax, Liu interviews his own mother about her acceptance of physical and mental abuse from his stepfather and ends up revealing his own knotted resentments and fears about family in the process. In interrogating his past relationships and building new ones, the young filmmaker confronts the dark, long shadow of traditional masculinity that has poisoned his life and that of his new friends without succumbing to the idea of its inevitability in the future. Not unlike skateboarding, Liu convincingly suggests that filmmaking is an outlet that not only supports creativity and expressions of inner life but also helps foster the kinds of understanding and empathy that may help mold better friendships and, perhaps, better friends.

21. Leviathan

A visceral experience that never leaves the confines of a massive fishing boat at sea. The camera is tossed into pits of fish guts and other detritus, strapped to the helm of the boat, and turned upward at a crooked angle to catch a flock of birds fluttering away. Nature begins to take on a uniquely chaotic tone here, scrambled into an assemblage of sounds both harsh and delicate, immediate images of churning waters and the labor of fishing for a living. The chosen style of the directors, Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel of the influential Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab, which also helped produced major works like Foreign Parts and Sweetgrass, creates a symbioses between the filmmaking and the work and atmosphere of the boat, getting at the bedlam of the process and the fractured yet feverish beauty that can come about through it.

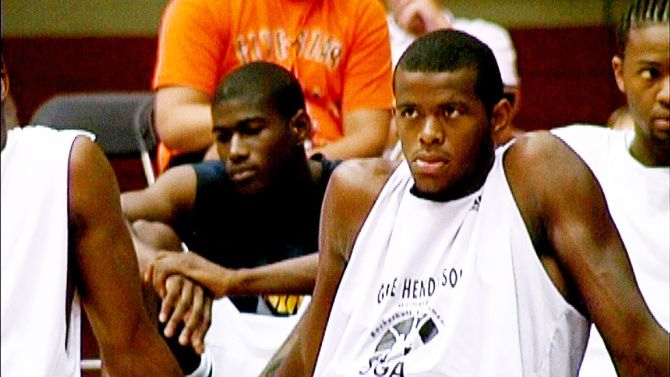

20. Lenny Cooke

From the outset, the story of the promising teenage basketball player Lenny Cooke doesn’t seem particularly unique. A star at his New York public school, Cooke short-circuited his career when his anti-authoritarian streak curdled into outright cockiness and stubbornness, making him comfortable with skipping practice and focusing more on carousing or goofing around then honing his skills alongside the likes of LeBron James and Carmelo Anthony.

What the Safdie brothers brilliantly lock onto in Lenny Cooke is the demands of maturity and focus in talented, young black athletes as contrasted against the brash, enviable freedom of sports celebrity that is impossible to escape. Cooke sees himself as the next Michael Jordan, but the work that goes into building a career like Jordan’s never occurred to the young player, and the disconnect sent him into obscurity. Years later, the Safdies catch back up with him – overweight and under-employed – and Cooke remains a hypnotic showman, even as his personal life seems to be quickly deteriorating.

Whether purposeful or not, the inventive and thoughtful fraternal directors create a distinct, intimate behavioral portrait of a would-be world-class athlete,and give Cooke his starring moment years after the one he hoped for slipped away.

19. Exit Through the Gift Shop

A document of the clandestine operation of high-grade graffiti artists becomes a searing indictment of the capitalistic systems that provide backing for many artists. Narrated wryly by Rhys Ifans, this wondrous and often hysterical history of modern art in micro follows the likes of Banksy, Shepard Fairey, and the French-based Zevs before trading their urgent, demanding, and criminal doings for preperations for the first major show for Mr. Brainwash, a.k.a. Thierry Guetta. Was Brainwash created for the movie or genuine? Is his work genius or garbage? Does it really matter when it’s all said and done? Banksy undermines and ridicules a culture that values the aesthetic of taste over actual taste on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, creating a boisterous, incisive riot that’s never quite as deep or flippant as it seems.

18. 13th

Though largely celebrated upon its release, there were more than a handful of critics who seemed to condescend to Ava DuVernay’s furious documentary for its seeming straightforwardness and lack of style. These people clearly didn’t watch the movie. Though not radical in her compositions, DuVernay’s exhilarating and unrelenting pace packs in a living history of America’s black population in the aftermath of the 13th amendment, creating a stark, convincing argument that slavery went away in name only in the U.S.A.

She places major figures, from Van Jones and Michelle Alexander to Angela Davis and, yes, Newt Gingrich, in places of work, scenes where you can fully sense the labor that went into building an abandoned warehouse or a towering building filled with dimly lit offices. The observations that DuVernay catches in her interviews may not be anything new to those who have read "The New Jim Crow" or the works of Ta-Nehisi Coates, but deployed as a barrage under DuVernay’s direction, a full-throated demand for equal rights and respect for black labor emerges. It’s not easy to shake, nor should it be.

17. Hale County

When you recall RaMell Ross’ unclassifiable debut feature, Hale County This Morning, This Evening, its impossible to make linear sense of it all. What comes to mind are smeared and smattered glimpses of life in the titular corner of poverty-wracked Alabama. Shots of older men and bright-eyed, nervous boys having their hair cut by talkative barbers and images of a young couple trying to put up a good front in the face of overwhelming responsibilities and disappointment come floating in. There is a volatile but familiar story at the heart of Ross’s film, that of two young African-American men struggling to find their paths after high school, and its told with ample, almost sensual detail. The power of Ross’s film, however, is in how vast and luscious his vision of his home is, divorced from time and soaked in the vagaries of light, focus, and color.

16. Cameraperson

What we get in Kirsten Johnson’s eloquent and emotional Cameraperson is a portrait of two careers, the chaotic one that exists now and the possible one that might have been or may still be. Made up of scenes and sequences from her time as a director of photography – she’s collaborated often with Laura Poitras and Kirby Dick – the film does more to illustrate the tension between technical, physically demanding work of filmmaking and the lofty, exhilarating ambitions that causes people to do the work in the first place better than a great deal of its timid ilk. Johnson films the view from her car speeding through tunnels with the same intimacy as a quiet discussion with a young working woman, summoning together a self-portrait that finds flashes of complex artist in both her passionate political subjects as her whimsical impulses to film her life outside of the calling that has otherwise all but consumed her being.