The best documentaries shine a light on social and political injustice, remind us of our history, teach us about the inner workings of our planet and universe, show us pockets of the world previously unfamiliar, and promote empathy for our fellow humans—empathy that comes from a broader understanding of humanity, an understanding that can often only be achieved by stepping into someone else’s shoes and living in their world, if only for a few moments or hours.

Of course, a single writer crafting a “best of” list for such an expansive, ubiquitous medium is a subjective endeavor; these lists often reveal more about the writer than the subject, so it’s with some trepidation that I look over mine and realize that the first five films are all about men, driven by hubris and ego, making or reflecting on decisions that have devastating consequences. “Delusional” is a word that could apply across the board, from the grizzly man who foolishly thought he had found a way to transcend nature’s food chain to the 28-year-old NSA whistleblower who may or may not have a Christ complex. There are the aging monsters who gleefully re-enact the murders of innocents they committed in the name of eradicating communism, and then there’s the architect of the Vietnam War, who glibly recounts decisions he made—decisions that caused the death of thousands—as if he were recalling an especially difficult chess game. And then there are the soldiers in the middle of it all, stationed in the most dangerous valley on the planet, fighting a war run by men who view them as expendable pawns.

The takeaway? Men are terrible.

The Fog of War: 11 Lessons From the Life of Robert S. McNamara (2003)

“Empathize with your enemy” is life lesson #1 from former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, but it could also be applied to filmmaker Errol Morris’s approach to interviewing McNamara for The Fog of War. Morris doesn’t just give McNamara a platform to explain/defend himself as the architect of an unnecessary war that traded thousands of innocent lives for political points; he probes deep into McNamara’s psyche to paint a nuanced, not-unsympathetic portrait of a man far removed from the daily realities of combat who made high-level decisions for soldiers that were, to him, little more than abstractions, chess pieces in a bigger game that would never be won.

Grizzly Man (2005)

“Nature here is vile and base.” Werner Herzog said that about the jungles of Peru during the production of Fitzcarraldo (the moment is captured in Les Blank’s 1982 documentary Burden of Dreams), but it could be the working thesis for the director’s body of work in the several decades that followed. Herzog’s obsession with the violence of the natural world and the quixotic men and women who think they can tame it is borne out in the story of Timothy Treadwell, an environmentalist who made it his mission to protect grizzly bears, going so far as to live among them for 13 summers at Alaska’s Katmai National Park. Mining hours of Treadwell’s own video footage of his time among the grizzlies along with interviews of wildlife experts and Treadwell’s friends, Herzog offers cautious salute to a man who foolishly thought he could transcend the natural order of things to find harmony among the violence. Treadwell’s tragic ending hammers home Herzog’s career-long point: in the primal battle of man vs. nature, nature always wins.

Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005)

Alex Gibney’s breakout film hinted at what would make him one of the most respected documentarians working today, and it holds up. Enron feels ahead of its time, shining a light on white collar criminals and corporate malfeasance happening on a scale previously difficult to imagine. The market manipulations perpetrated by Enron heavies Kenneth Lay and Jeffrey Skilling in some ways foreshadows the financial skullduggery that would lead to the 2008 financial crisis, and Gibney’s 2010 post-mortem Inside Job feels like the Enron sequel we wish we didn’t need.

The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters (2007)

There’s so much to love about The King of Kong. Steve Wiebe is one of cinema’s great underdogs. Billy Mitchell is an utterly unique villain-foil. The weird world of vintage arcade game score-besting and the characters who populate it are presented with great love and affection by director Seth Gordon (Horrible Bosses), whose impeccable comic timing and eye for the absurd quickly opened some major doors in Hollywood. But the best thing about The King of Kong is the way Gordon presents this fringe world full of misfits and weirdos as just another iteration of the American obsession with pastime as competition, and the man-boys who devote their lives to it. It could just as easily be about football.

Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father (2008)

Shot on a shoestring budget over several years by amateur filmmaker Kurt Kuenne, Dear Zachary starts out as a moving memorial to Kuenne’s deceased best friend, Andrew Bagby, a family physician who was murdered outside Latrobe, Pennsylvania in 2001. Kuenne initially set out to create a video scrapbook meant only for Bagby’s family and his unborn son Zachary, but as the investigation of Bagby’s death yields a surprising prime suspect, Kuenne’s project evolves into something heartbreaking and unbelievable. Produced in the early days of the digital video revolution, it still serves as a potent example of what can happen when you remove the financial gatekeepers and democratize a medium. Part true-crime thriller, part indictment of an ineffectual legal system, Dear Zachary is, ultimately, an anguished howl of rage in the face of incomprehensible tragedy and deferred justice.

Anvil: The Story of Anvil (2008)

In 1984, Canadian heavy metal band Anvil was on the cusp of success, touring the globe and performing to sold-out crowds alongside future giants of the genre like Scorpions and Bon Jovi. Unfortunately, success never fully materialized, and the band slipped into obscurity as its peers took over the world. 20 years later, the Anvil guys are working blue collar jobs and playing gigs at a local sports bar when they receive an unexpected offer to tour Europe, prompting an outrageous comeback odyssey.

Anvil is, first and foremost, a sentimental story about the second chances life sometimes unexpectedly hands us. It’s also frequently hilarious, and the mischievous comparisons to “Spinal Tap, but in real life” are not unwarranted. But Anvil’s engine is its big, beating heart, and director Sacha Gervasi (who worked as a roadie for the band in the mid-80s) loves his subjects too much to let the comedy ever stoop to mockery.

Restrepo (2010)

Is there another documentary as effective as Restrepo at depicting the human cost of war? Maybe, but none so laser-focused or viscerally charged as Sebastian Junger’s and Tim Hetherington’s 2010 masterpiece. Shot over 15 months in 2007/2008 in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley (commonly referred to at the time as “the most dangerous place in the world”), the film follows the soldiers of Second Platoon, Battle Company as they fight to keep Taliban insurgents at bay while navigating a delicate relationship with the locals. The unseen enemy is everywhere; firefights with combatants hiding in the hills are a daily fact of life, and Hetherington and Junger bravely/foolishly stay on the soldiers’ heels every step of the way.

Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010)

French immigrant Thierry Guetta, obsessed with videotaping every moment of his life, sets out to make a documentary about street art after learning his cousin is world-famous street artist Invader. As Guetta immerses in L.A.’s art scene, he befriends the mysterious artist Banksy, and, eventually, creates his own artist persona in Mr. Brainwash. It just gets weirder from there.

At the peak of the art world’s breathless speculation surrounding the identity of Banksy (Is he even real? A group of people? The guy from Massive Attack?), Exit Through the Gift Shop dropped like a bomb, further obfuscating the question of “Who is he?” with a “documentary,” directed by Banksy, that purports to be non-fiction but might or might not be a put-on. Whatever the case, this is a grandly entertaining statement about the nature of art and the worship of artists that carries the ring of truth—whether or not the movie is the world’s most elaborate prank.

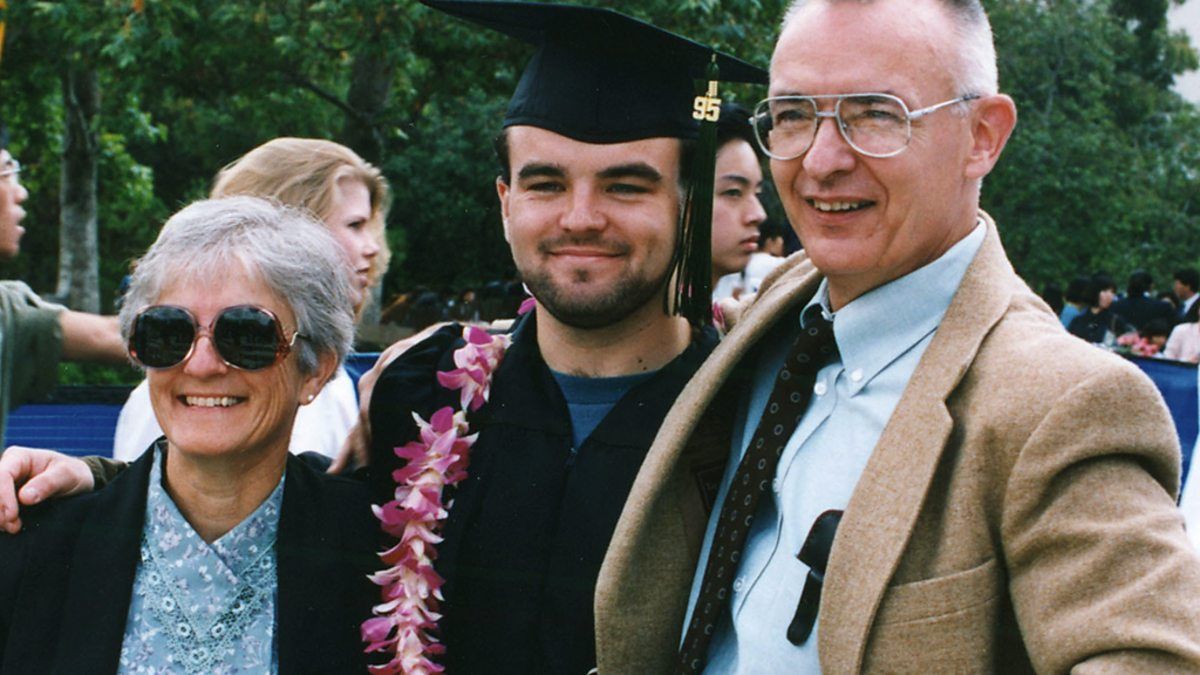

Man on Wire (2010)

History is full of foolhardy daredevils who pushed their limits and tempted fate for the sake of fame and fortune, and Philippe Petit might be the foolhardiest of them all; the French tightrope artist famously walked a high wire between the recently constructed Twin Towers in 1974. In Man on Wire, director James Marsh lovingly reconstructs the scheming and preparation that made the big walk possible while also exploring the obvious question: What would possess someone to do such a thing? (For maximum effect, viewers should follow Man On Wire with the last 30 minutes of Robert Zemeckis’s The Walk.)

Jiro Dreams of Sushi (2011)

For some creators, obsession is a violent, dysfunctional force that yields beauty only after chaos has had its day. For sushi master Jiro, obsession manifests in the quiet precision of his knifework and the austere, unassuming environment of his restaurant Sukiyabashi Jiro, a 10-seater closet-sized room, located in a Tokyo subway station, that serves the best sushi in the world. The film is as gentle as its subject, and director David Gelb’s balletic approach to shooting food (complete with Philip Glass and Max Richter music cues) has since been adopted by a slew of high-brow culinary shows—including the Netflix series Chef’s Table, which Gelb created.

Stories We Tell (2012)

On paper, the boilerplate summary of Stories We Tell might seem insular and familial to the point of self-indulgence, but there’s far more going on here than you think. Sarah Polley, an accomplished actor and filmmaker, interviews her sprawling family, spread across two marriages, to better understand the inner workings of her late mother DIane, a gregarious stage actress who struggled to balance her love of life with her commitment to family. Polley depicts her childhood memories of her mother through impressively realistic home movie recreations and dramatic voice-over delivered by her father Michael—the latter of which takes on a bittersweet irony when family secrets are revealed and the full scope of Polley’s intent is made known.

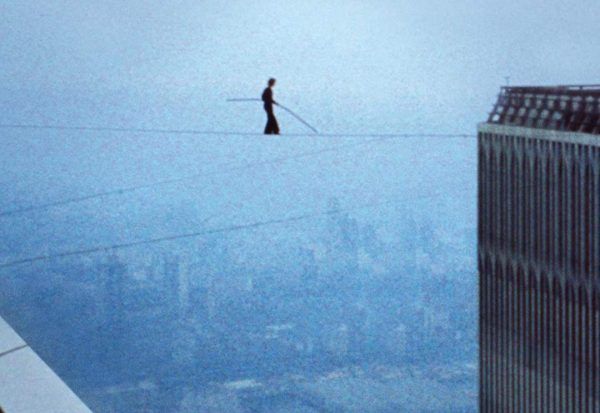

How to Survive a Plague (2012)

How to Survive a Plague is, arguably, the definitive broad account of the AIDS epidemic in the United States, as told through the stories of ACT UP and TAG, the New York City activist groups that, from the earliest days of the epidemic, fought tooth and nail on behalf of victims, demanding action and treatment while the U.S. government turned its back on those affected and a homophobic society culturally quarantined them. Utilizing hundreds of hours of archival footage along with talking head interviews from players like activist-playwright Larry Kramer and former NYC mayor Ed Koch, director David France crafts an exhaustively realized work of historical journalism that doubles as a tribute to the brave outsiders who fought not just for survival, but for acceptance.

The Act of Killing (2012)

The most disturbing thing—and there are many—about the aging killers at the center of The Act of Killing is the unbridled joy they take in recounting their numerous murders. Anwar Congo claims to have killed over 1,000 Indonesian citizens—suspected communists—during the Indonesian genocide of 1965-66, and he’s eager to show filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer exactly how he did it. To that end, Congo and his fellow henchmen restage, with Oppenheimer’s assistance, a handful of their favorite killings. Shot like low-rent straight-to-video gangster films complete with gallons of fake blood, Oppenheimer’s deeply unsettling dramatic recreations (starring the killers as themselves) dissect not just the dark hearts of these men, but the influence American entertainment had on them, and the lingering trauma inflicted on an entire country by their actions—the effects of which they’re either gleefully proud of or oblivious to. Unlike their Western counterparts, these men don’t use the creeping threat of communism to pretend to noble intentions or justify their actions—they’re proud gangsters who strut around town knowing the fear they still command.

Blackfish (2013)

When Blackfish first hit theaters in 2013, SeaWorld embarked on an extended smear campaign against the film—which used the sad case study of Tilikum the killer whale to criticize the theme park’s practice of exploiting captive orcas for profitable entertainment—publishing an open letter calling the film “inaccurate and misleading,” among other things. And yet, three years after the film’s release, SeaWorld announced it would no longer breed orcas and would phase out live performances. As of this year, there are still a handful of theatrical orca shows at three SeaWorld locations, but the needle is moving in the right direction, thanks largely to Blackfish’s success in swaying public opinion.

The Overnighters (2014)

The Overnighters starts out like a modern Grapes of Wrath: While the rest of the country is in the throes of the worst economic depression since The Great one, the town of Williston, North Dakota, is ground zero for the state’s oil boom and a beacon of hope for thousands of would-be laborers who flock from all over the country in search of a living wage. The small community of 17,000 isn’t prepared for the massive influx of strangers—some of whom are less than model citizens—and residents are on edge as more and more desperate workers arrive, many of whom are forced to sleep in their cars and scrounge for necessities.

Meanwhile, pastor Jay Reinke has converted his Concordia Lutheran Church into a hostel of sorts where those seeking work can find food, shelter and ministry while they get on their feet. As his town and congregation turn on him and his family questions the wisdom of his generosity, Reinke remains steadfast in his commitment to the struggling and downtrodden. But that commitment comes with a cost, and a startling third act twist brings into focus the push and pull between Reinke’s New Testament altruism and the church’s Old Testament doctrine. Director Jesse Moss (The Family), shooting as a crew of one, passes no judgment on the townspeople, the overnighters or Reinke. In lesser hands, the subject could have been reduced to another sensational entry in the poverty porn and religious scandal subgenres, but The Overnighters is clear-eyed, respectful, and full of humanity.

Citizenfour (2014)

Laura Poitras’s real-time portrait of NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden has all the ingredients of a geopolitical thriller, which is perhaps why Oliver Stone’s dramatic recreation of the same events in 2016’s Snowden seemed so inert and redundant. Snowden, a young, earnest NSA analyst who exposed the machinations of a global surveillance apparatus and its troubling implications for the privacy and civil rights of American citizens, tells his story to Poitras and Guardian journalists Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill while hiding in an undisclosed hotel somewhere in Moscow. While the dominant conversation in the media surrounding Snowden was driven by the question “Is he a hero or a traitor?” The conversations captured by Poitras inside that hotel room suggest that the answer ultimately doesn’t matter; Snowden might be both, or neither, but he’s a true believer, and the implications of what he revealed should alarm anyone who values the idea of a free democracy. Citizenfour is a vital historical document of one of the most important chapters in the 21st Century.

Virunga (2014)

Early in Virunga, filmmaker Orlando von Einsiedel’s camera lingers for long stretches on the astounding beauty of the Congo’s Virunga National Park, home to the world’s last mountain gorillas. One might be forgiven for mistaking isolated passages for an episode of Planet Earth, but it’s the man-made tragedy lurking just off-screen during these sequences that make Virunga one of the most important documentaries of the century.

The film opens with the burial of a Virunga park ranger, followed by a harrowing opening credits sequence in which 130 years of oppression and exploitation of the Congo by Western colonial forces are recounted through archival footage and terse title cards. It’s within this context that von Ensiedel and French investigative journalist Melanie Gouby embed with the rangers who fight to protect their park—home to thousands of people in addition to endangered wildlife—as the region descends into war with the Congolese Revolutionary Army (allegedly sponsored by neighboring states) and the British oil company Soco International seeks to exploit Virunga’s vulnerability for its natural resources. As the verdant beauty of the region is fogged by smoke, gunfire and bloodshed, Virunga becomes a desperate clarion call for the world to sit up and pay attention.

13th (2016)

With great insight, righteous anger, and incendiary soapboxing, director Ava DuVernay dissects all of the ways in which one clause of the 13th Amendment effectively ended one form of slavery while codifying another, more insidious form of African American disenfranchisement. Tracing the ratification of the amendment at the end of the Civil War through convict leasing during reconstruction, Jim Crow, the war on drugs, mandatory minimum sentencing, police violence and the rise of the prison-industrial complex, DuVernay uses interviews with scholars, activists, journalists and politicians to connect the dots across 150 years of institutional oppression. It’s an infuriating but deeply important film that should be required viewing in every high school civics and history class.

I Am Not Your Negro (2016)

How do you distill a life and legacy as important as James Baldwin’s into a two-hour film? By letting the man speak in his own words. Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro eschews the formula of biography for something far more poetic and poignant, using the unfinished manuscript of Baldwin’s memoir “Remember This House” to craft an impressionistic collage of the man as writer, social critic and civil rights leader. With quiet restraint, Samuel L. Jackson gives voice to Baldwin’s words in a haunting voice-over that’s one of the actor’s finest achievements.

Author: The JT Leroy Story (2016)

In the late 90s, a teenage writer named JT LeRoy took the New York publishing world by storm. Born in West Virginia, LeRoy was a ready-made story for the big-city literati: a survivor of sexual abuse with a history of homelessness and prostitution, HIV positive, and a damn good writer who channeled his dysfunctional relationship with his drug-addicted mother into starkly beautiful short stories. For a time, despite his severe aversion to public appearances, LeRoy was the toast of the town and courted celebrity admirers like Billy Corgan, Asia Argento and Winona Ryder. But there was a problem: LeRoy didn’t really exist—he was the creation of Laura Albert, a 30something phone sex worker addicted to calling emergency help lines. When the New York Times exposed the ruse, Albert was promptly excised from the literary community that had exalted LeRoy.

In Author: The JT LeRoy Story, director Jeff Feuerzeig (The Devil and Daniel Johnston) lays out the “How?” of the hoax in compelling detail, but it’s when he gets to the “Why?” that Author really soars. In an unorthodox move, Feuerzeig skips over the haters and critics and instead gives Albert the majority of screen time, allowing her to explain and analyze herself in great detail without regard for counter opinions, despite her history as an unreliable narrator. Predictably, this approach was met with handwringing by some critics who mistook Feuerzeig’s singular focus on Albert as sloppy, one-sided filmmaking, but the director isn’t interested in setting the historical record straight or exacting justice on behalf of privileged fans suffering from hurt feelings—he’s interested in the relationship between Albert and her creation, and the way LeRoy’s fictional traumas reflected and soothed Albert’s very real ones. For Feuerzeig, the salacious literary scandal at the center of Author is just a conversation starter for far more important issues of identity, trauma, and authenticity.