What does a film score sound like? That’s a broad question, but it becomes easier to answer once it’s broken down into parts. What does the score for a period drama sound like? What about the score for a science fiction movie? A horror movie? A comic book movie? All of these genres have their own tropes and conventions, and that goes for their scores, as well.

There’s nothing wrong with these tropes: after all, they only become tropes in the first place because they’re proven to work. But too often, film scores fall into familiar patterns that betray a certain complacency, a willingness to be merely functional. The same horn fanfares are deployed at the same triumphant moments. The same ominous drones play in the background of suspenseful scenes. The same romantic strings swell during the big kiss. It’s a problem that exists even in the upper echelons of film scoring, which are dominated by the same few names: Hans Zimmer, Alexandre Desplat, Thomas Newman, et cetera. All of them are brilliant composers, but it sometimes feels as though they’re satisfied coloring inside the lines.

In recent years, the best, boldest film scores were not composed by those familiar names, but by artists from the world of independent music. Alternative musicians composing for film is not a new phenomenon: avant-garde electronic artists like Wendy Carlos and Vangelis found success scoring films back in the 70s and 80s, and one of the most iconic scores in film history was written and performed by an obscure zither player. All the same, recent independent musicians have made striking, unusual choices that enhanced their movies, garnered acclaim, and shook up the film score landscape.

Jonny Greenwood - There Will Be Blood (2008)

If Jonny Greenwood never wrote a single note of music for a film, his legacy would be secure. As the guitarist for Radiohead, he is a member of one of the best-loved bands of all time, and he’s directly responsible for some of their greatest material. Those shotgun-blast riffs in “Creep” were his doing, as was most of “Paranoid Android.” But when Paul Thomas Anderson came calling, he wanted to make use of Greenwood’s talents as a composer and arranger.

Greenwood had composed before, writing standalone classical pieces and string arrangements for Radiohead songs, but he was not a typical film composer. A devotee of avant-garde figures like Olivier Messiaen and Krzystof Penderecki, he wrote arrangements that gave session musicians fits of nervous, “how the hell am I supposed to play this” giggles. But then, There Will Be Blood wasn’t a typical period drama. The story of a black-hearted oil baron in the early 20th century, it occasionally feels like a horror movie, exposing the grotesque, murderous id of American capitalism.

Accordingly, Greenwood’s score for There Will Be Blood is stark, severe, and more than a little frightening. “Open Spaces” evokes the majesty of the Western landscapes Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) traverses in his quest for oil, but unresolved chords hang in the air like veiled threats. The strings on “Henry Plainview” creep up and down the microtonal scale, a distant siren warning of a danger that’s already far too close. And the bustling “Future Markets” reimagines the engine of progress as a hellish train barreling towards the coast.

Although it drank its competitors’ milkshakes in 2007, the score was ineligible for the Oscars, as it repurposed previously-recorded material (excerpts of Greenwood’s “Popcorn Superhet Receiver” and “Convergence” were used.) No matter: There Will Be Blood established Greenwood as a singular talent in film scoring, and opened the door for sinister, dissonant scores to come.

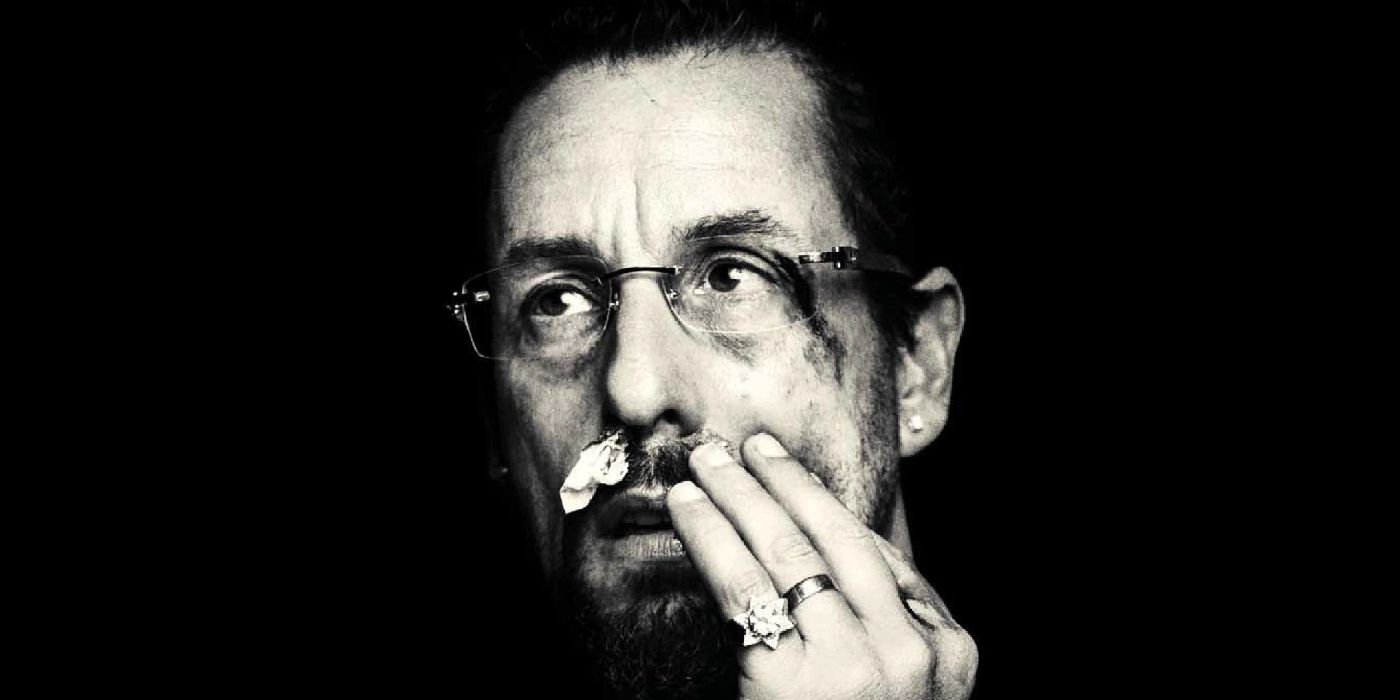

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross - The Social Network (2010)

In the opening scene of The Social Network, a young Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) stalks back to his Harvard dorm after a bad date. The camera views Zuckerberg from a distance, only occasionally focusing on him; otherwise, he’s incidental, another kid in a gray hoodie fading in and out of the background. The music is an ambient piece called “Hand Covers Bruise”; it churns and drones, a cloud of processed cello occasionally parted by a placid piano figure. It sounds like a new dawn, and yet it doesn’t quite feel hopeful. Something huge is about to happen. But is it something good?

The arrival of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross represented, on a smaller scale, a paradigm shift similar to the rise of Facebook. Unlike Facebook, of course, it was an unambiguously good thing. There had been synth-heavy film scores before, but most were for genre movies, and those that weren’t (such as Vangelis’ score for Chariots of Fire) functioned much like an orchestral film score anyway. It was rare for a prestige movie like The Social Network to have an ambient score; after Reznor and Ross won their first Oscar, the industry began to explore other composers (including a few on this list) who emphasized texture over melody.

If one were to go back in time to 1993 and say that Trent Reznor would one day lead a new vanguard in film scoring, few people would believe them, least of all Trent Reznor. As Nine Inch Nails, Reznor made bruising, industrial music that seethed with violent rage. His music videos were routinely censored, if not banned outright; he won a Grammy for a song that features the words “fist-fuck.” But despite his provocations, he was more than just a shock-rocker; he possessed a peerless ear for musical texture and emotional resonance.

The Social Network’s score works so well because it matches the rhythm of the movie, but not necessarily its tone. The music is as active and intricate as the mind of its protagonist, but it plays off of what happens in intriguing ways. An uneventful walk home brims with possibility and significance thanks to “Hand Covers Bruise.” The thrilling, propulsive “In Motion” plays as Zuckerberg codes the most efficient way to creep on girls. And throughout, there’s a darkness that colors even the most triumphant moments. Now that the public knows screwing over the Winklevosses was one of Zuckerberg’s lesser sins, it feels oddly prescient.

Mica Levi - Under the Skin (2013)

From the first notes of her band’s debut album, it was clear that Mica Levi was no ordinary indie-pop artist. “Vulture” begins with the familiar acoustic guitar being used in a decidedly unorthodox way: choking the strings as hard as they can, Levi pounds out a gnarled, clanging beast of a chord. At first, it sounds only slightly more musical than Jake Peralta’s guitar-based interrogation method; then the rest of the band kicks in, and “Vulture” becomes a total banger.

More than their classical training, that outside-the-box thinking made Levi a perfect choice for Under the Skin: like Levi, it simultaneously satisfies and defies the expectations of its genre. A sci-fi horror movie starring Scarlett Johansson as an alien seductress who sucks out men’s innards, it subverts the lurid promise of its premise, offering a creeping exploration of body horror and human cruelty.

Levi’s score for Under the Skin serves as a reflection of the alien’s mindset; this means it’s cold, strange, and creepy as hell. “Creation” soundtracks the alien’s “birth” with a microtonal swarm of buzzing violas. The sinister “Lipstick to Void” lopes with the patience of an apex predator, its whining strings and steady heartbeat rhythm adding a note of uncomfortable sensuality. Most compelling of all is “Love”, a swooning, achingly tender synth reverie that represents the alien’s burgeoning humanity.

Under the Skin disappointed at the box office, but its critical praise ensured that Levi’s efforts didn’t go unnoticed. A few years after its release, the gawky young indie composer was nominated for an Oscar, having scored a biopic for Jackie Kennedy. A move to the mainstream? Hardly. Levi’s score for Jackie is as disorienting as anything else they’ve done. The world of film scores moves slowly, but by now it was starting to catch up.

Daniel Lopatin - Uncut Gems (2019)

Daniel Lopatin, better known as Oneohtrix Point Never, is one of the most eclectic and influential electronic musicians of the past decade. His music interrogates the concept of nostalgia, transforming the cultural detritus of past decades (70s new age, 80s corporate pop, 90s commercials, etc.) into poignant, psychedelic art. No two of his albums sound exactly alike, and some of them didn’t sound like anything else out there at the time. How many people can credibly claim to have invented vaporwave?

Lopatin had already scored the Safdie brothers’ previous movie, Good Time, using his familiar array of retro synths to express the anxiety of a New York City fuck-up. He could have done exactly the same thing for Uncut Gems, another movie about an anxious New York City fuck-up, but Lopatin and the Safdies had other ideas. The score for Uncut Gems forgoes the synthwave-esque pulse of Good Time for a spacey, new age sound: less Kavinsky, more Tangerine Dream. Synths twinkle and shine like distant stars; a choir jumps in sometimes to chant along; occasionally, there’s a glassy saxophone solo.

There’s an element of mockery there (there’s a piece called “Fuck You Howard,” after all), but the music suggests something deeper than the story of a dime-a-dozen Diamond District dirtbag. Music like “The Ballad of Howie Bling,” “Windows” and “Uncut Gems” highlight the optimism that’s at Howard’s core, and even provides the greedy schmuck a bit of dignity. Maybe this is how he wins.

Hildur Guðnadóttir - Joker (2019)

There has been one name missing in this article so far, and fans of film music likely already know whose name that is. Jóhann Jóhannsson started his musical career in a noise pop band called Daisy Hill Puppy Farm, immersed himself in avant-garde classical music, and became the kind of composer whose albums got the Best New Music designation on Pitchfork. Jóhann’s mainstream breakthrough as a film composer didn’t come until 2013, with Denis Villeneuve’s Prisoners, but he made an impact almost overnight: it became a go-to “temp track” for other filmmakers and composers, heavily influencing the sound of their own scores. A flurry of acclaimed soundtracks followed – The Theory of Everything, Sicario, Arrival – and Jóhann looked as though he could become a giant of film scoring on par with Hans Zimmer.

Then, in 2018, tragedy struck. Jóhann died of heart failure at the age of 48, and the medium lost one of its boldest talents.

Hildur Guðnadóttir likely knew there was no replacing Jóhann. She also likely knew that she was gifted enough in her own right that she didn’t have to. An experimental cellist who recorded with artists like The Knife and Sunn O))), she frequently collaborated with Jóhann, and when she started scoring films of her own she honed his sensibilities to a lacerating edge. She broke out with the doom-laden score for Chernobyl; a couple of months later, she had an even bigger success.

Joker is a deeply flawed movie that has two major things going for it: the performance of Joaquin Phoenix as the title character (also known as Arthur Fleck) and Hildur’s score. Her cello groans mournfully, sounding like the only instrument in the world even when backed by a hundred-piece orchestra. There are moments of icy, crackling dissonance, and even moments where the score gets downright noisy, but it hits hardest when it empathizes with Joker’s tortured protagonist. The scene where Fleck quietly dances along with Hildur’s cello in a filthy public bathroom is a moment of genuine, lyrical beauty in a film that often strains for profundity.

In early 2020, a little under ten years after Reznor and Ross won for The Social Network, Hildur won the Oscar for Best Original Score. No longer was the category dominated by staid, tasteful chamber orchestras; the dissonant, strange, and alternative now have their place in prestige film.