Francis Ford Coppola has been a titan of cinema for over half a century. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Coppola, alongside contemporaries like Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas, ushered in the New Hollywood wave of American filmmaking. This young, new generation of directors created films that deviated from classical Hollywood structure and embraced more experimental and unorthodox narrative practices and characters. This year marks 50 years since Coppola’s The Godfather proved that New Hollywood was here to stay, and began Coppola down a legendary career path that few directors have matched.

While Coppola may be best known for The Godfather, the quality of his resume extends far beyond the gangster classic. From the beaches of Vietnam to the ornate architecture of Transylvania, Coppola has showcased his directorial skills in a slew of genres. After not making a movie since 2011, Coppola is coming back for one final movie, Megalopolis, which he is self-financing for $120 million. Before that releases, let’s take a look back at nine other great Francis Ford Coppola movies that aren’t The Godfather.

The Rain People (1969)

Often overlooked because it is Coppola’s film directly preceding The Godfather, for that reason, The Rain People is easily the director’s most underrated film. Shirley Knight plays Natalie, a housewife who begins to look for liberation after finding out she is pregnant. Unfolding as a road movie, the film follows Natalie’s search for freedom as she encounters several men who try to win her affection. Among the men is a retired football player with a head injury played by James Caan and Robert Duvall as an intimidating state trooper. Caan in particular is exceptional in a heartbreaking performance that gains its power from how underplayed it is. The Rain People is a film that is much more about the people taking the journey rather than where that journey leads and Coppola sketches out some fascinating characters to populate his road trip.

One From the Heart (1981)

Despite not having an exorbitant budget, One From the Heart is often referred to as the movie that broke Francis Ford Coppola. Financed primarily through Zoetrope Studios (a production company founded by Coppola and George Lucas), the film managed to scrape back just over $600,000 of its $26 million budget. And if this is the film that sunk Coppola, at least he went down swinging. One From the Heart is an audacious, sprawling musical that bleeds romance at the edge of every frame. Lensed by legendary cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and set to a bluesy soundtrack by Tom Waits, the film looks and sounds gorgeous as it explores the struggling relationship of Hank (Frederic Forrest) and Frannie (Teri Garr). Struggling to live together after five years in a relationship, both Hank and Frannie meet the person of their dreams, but they must question where their love truly lies. While the film wasn’t a success, you have to admire the ambition of Coppola at a time when he could have easily played it safe.

Rumble Fish (1983)

In 1982, Coppola released two adaptations of S.E. Hinton novels. Where The Outsiders is more of a direct and faithful adaptation, Coppola goes for more of a spiritual adaption of Rumble Fish. Instead of taking the words directly off the page, Coppola aims more to capture the atmosphere and thematic power of the text. Starring Matt Dillon (who also appears in The Outsiders) as Rusty, a tough and sensitive troublemaker, and Mickey Rourke as his older brother called The Motorcycle Boy, the two often reminisce about the days when every day was another gang war. Nowadays, Rusty feels burdened by having to live up to his brother’s reputation and is just itching for a chance to prove himself. The gritty story is contrasted strikingly with Coppola’s abstract approach to the material. With an experimental score and a black and white visual style, Coppola chooses his moments carefully when to break from his established aesthetic. Rumble Fish is a startlingly expressionistic film adapted from a well-known author and proved Coppola could still be breaking new ground more than ten years after The Godfather.

Peggy Sue Got Married (1986)

A relatively low-stakes affair for a time-travel movie, in Peggy Sue Got Married, Coppola uses his time-bending premise primarily as a means to deepen a character study rather than present an original plot. Coming out one year after Robert Zemeckis’s Back to the Future, it’s understandable why Coppola turned to a burgeoning genre after he began the 1980s with a couple of box office failures that caused him to go into debt. In the film, Kathleen Turner plays Peggy, a woman who, during her 25-year high-school reunion, is inexplicably launched into the past all the way back to her senior year of high school. Forced to confront the decisions of her past, Peggy must choose which choices to make for a second time and which to change. It’s not exactly the rollicking adventure that Zemeckis’s film was, but Coppola explores his themes of eternal youth with a delicate hand, and the film is rounded out by an excellent supporting cast that includes Nicolas Cage, Joan Allen, and even a small performance from a very young Jim Carrey.

Tucker: The Man and his Dream (1988)

The story of a frustrated creator, Preston Tucker (Jeff Bridges) has spent a long time dreaming about revolutionizing the automobile industry with his 1948 Tucker Torpedo. For Coppola, the 1980s were a decade where his studio experiences were a revolving door of frustration. In Tucker: The Man and his Dream, Coppola translates that vexation into his main character’s obstacle-ridden path to success. What makes the film compelling is Tucker’s unrelenting optimism. You can’t help but root for the scrappy guy making his own cars in the barn next to his house. But when his can-do attitude is inevitably greeted harshly by the automotive industry executives, his disappointment is only that much more saddening. Bridges is effortlessly likable as the titular visionary inventor, and the film works both as an enjoyable but disheartening view of capitalism in America as well as a metatextual exercise for Coppola to vent some of his own frustration.

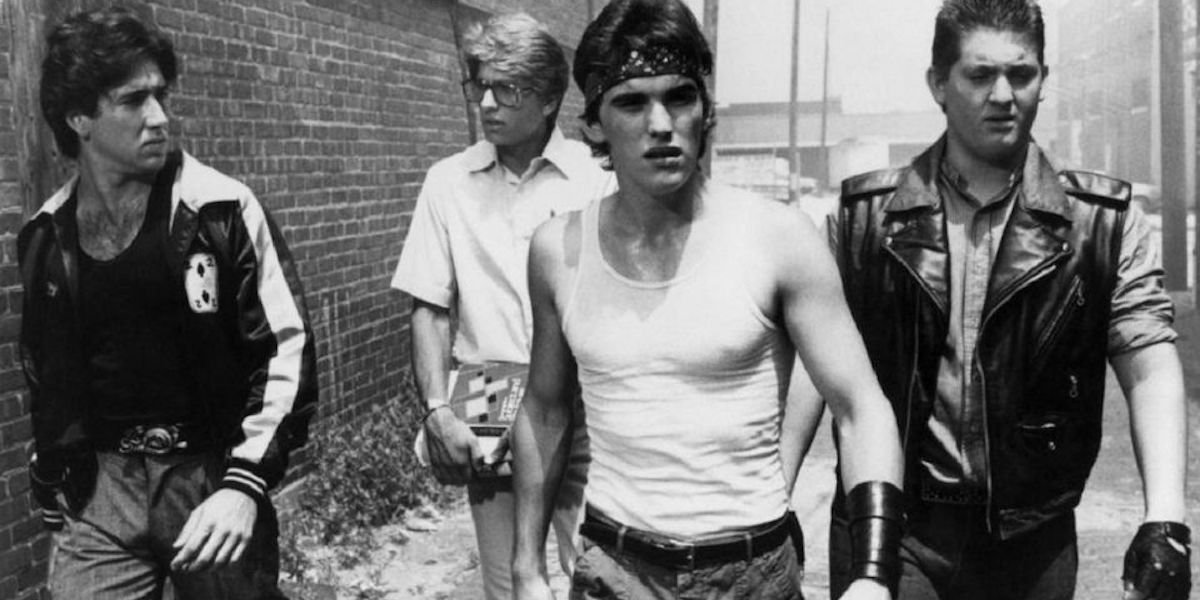

The Outsiders (1983)

Playing like the less audacious counterpart to Rumble Fish, Coppola’s adaptation of the classic S.E Hinton novel leans into the nostalgia of his 1960s-set youth gang drama. Tensions between rival gangs the Socs and Greasers are at an all-time high after one of the Socs is killed, forcing two Greasers, Ponyboy (C. Thomas Howell) and Johnny (Ralph Macchio), to go on the run. A dizzying and stylish story, the film is also a showcase for a slew of young actors who would grow up to be stars. The list is enormous (Matt Dillon, Patrick Swayze, Tom Cruise, Rob Lowe, Emilio Estevez, and Diane Lane), and Coppola gives them a striking and evocative world to populate. Coppola perfectly captures the sorrow of Hinton’s words as he expresses the sense of mourning for the lost generation of young boys that the gangs represent. Where Rumble Fish gets points for ambition, The Outsiders works perfectly as an adaptation that captures the spirit of the classic novel.

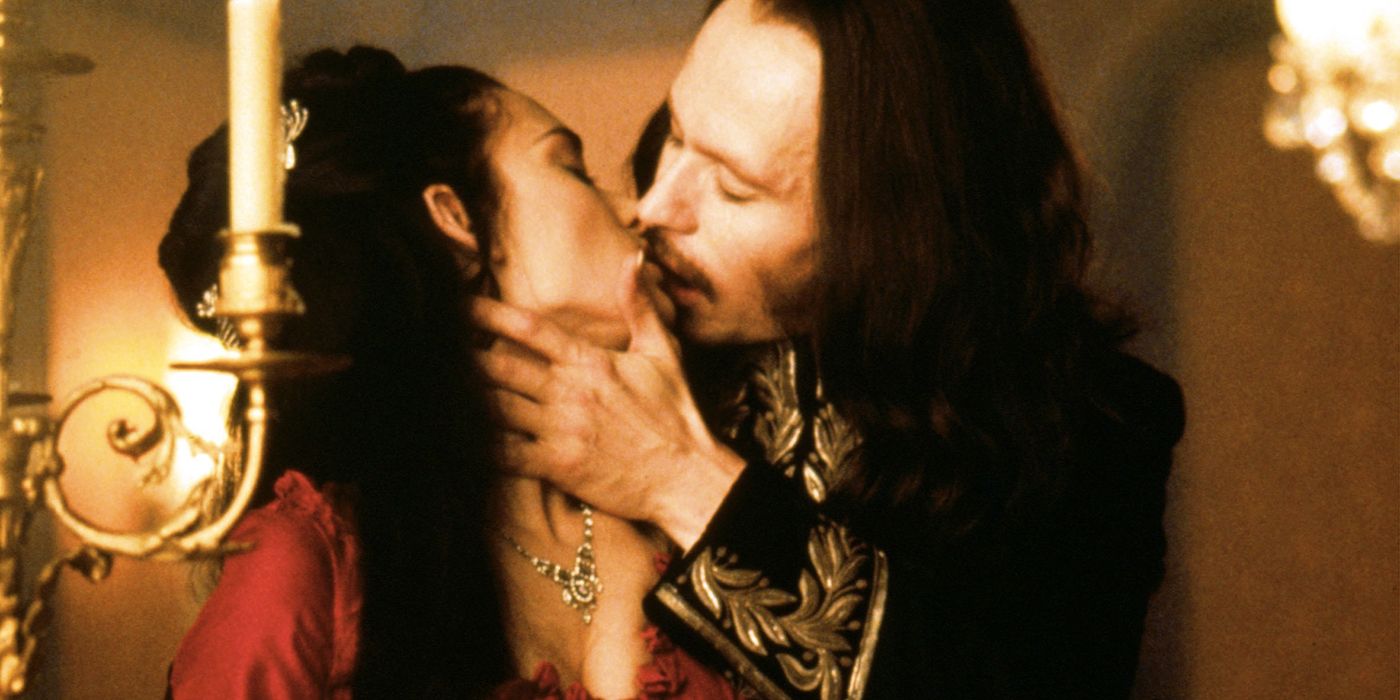

Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992)

Perhaps it’s a bit more of an atmospheric exercise than a showcase for acting prowess, but Bram Stoker’s: Dracula proves how much fun Coppola can have even when working in a genre he is less familiar with. With its brightly colored costumes and ornate sets, Coppola uses his gothic horror setting as a means to heighten the campy tone of his film. While Keanu Reeves may not be giving the best performance of all time as the solicitor Jonathan Harker, Gary Oldman more than picks up the slack as he delivers a haunting and melancholy performance as the titular Count Dracula. Coppola directs the romantic, phantasmagorical story with such sensual visual splendor, so much so that it is easy to understand why critics at the time were overwhelmed by the artistry on display, from all departments of the film. Today, Coppola’s take on Dracula has had a resurgence in popularity, and it is now often placed near the top of his stellar filmography.

Apocalypse Now (1979)

In one of the definitive movies about the Vietnam War, Coppola adapts Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness and delivers a harrowing and unforgettable film about the futility of war as well as the psychological effects it has on a person. When Captain Benjamin L. Willard (Martin Sheen) is tasked with tracking down and assassinating a rogue Special Forces Colonel, he leads a group of men into the heart of the jungles of Vietnam. Epic in scale but intimate in its psychological examination of its characters, Coppola’s 1979 masterpiece is also well known for its tumultuous filming process. The nightmarish production becomes tangible onscreen, but it works to the film’s advantage as the film’s grueling 16-month production heightens the psychological torment visible on the actors’ faces. Between the helicopter flight set to Richard Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries and Colonel Kurtz's (Marlon Brando) haunting final monologue, Apocalypse Now has plenty of moments you won’t soon forget.

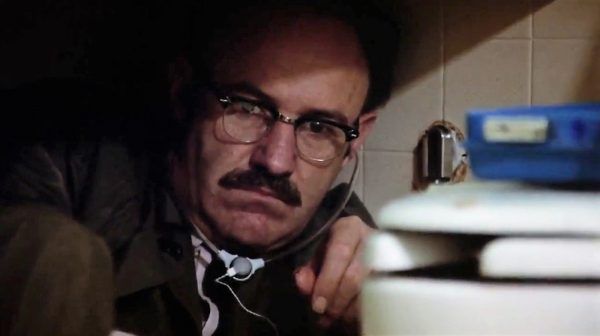

The Conversation (1974)

A paranoid political thriller starring Gene Hackman in one of his greatest performances, The Conversation is one of the best films from a decade overflowing with great thrillers. Hackman plays Harry Caul, a surveillance expert who becomes obsessed with a cryptic conversation he records between a young couple. Trying to discover if the couple is in danger or involved with a larger conspiracy, Caul’s obsession threatens to send him spiraling way over his head into a conspiratorial storm. As Caul digs himself deeper into his fixation, his alienation from the outside world becomes amplified. While primarily a thriller, the film also acts as a profoundly lonely character study, an examination of the cost of Caul’s compulsion. As government surveillance and intrusiveness have become even more hot-button issues, The Conversation has only gotten better with age. And if you’re not impressed enough yet, Coppola released this film the same year as The Godfather: Part II.