What makes the 1960s such an interesting decade for horror films is that—without any build-up or warning from the previous decade—the genre started off so shocking in 1960 that it was too much for most audiences. Like pulling off an adhesive band-aide very fast—only to cause more pain and needing to bandage it up again—1960 released a cluster of classic shockers that ratings boards and audiences didn’t know how to react to many of them other than banning and hoping to not see such horrors again.

The American Production Code (with strict rules on blood, garments, language, beds and even toilets) first started to erode with Psycho, and audiences saw things they hadn’t ever seen before. Not just a bloody shower scene, but also an unmarried woman lounging in a bra, and the same woman flushing a toilet. Psycho certainly was successful in the States, but studios thought only Hitchcock could nudge people along that quickly and audiences would revolt if anyone else indulged in such debauchery (some revolted anyway). Abroad, Hitchcock had to edit out most scenes with visible blood on hands, visible shadows of a breast, etc. And in the same year, Eyes Without a Face was a movie without a release date in many countries for its facial incisions; Peeping Tom was a movie that ruined the career of one of the world’s most beloved filmmakers; and Black Sunday was banned.

Those films all focused on ritualistic killers. After 1960, the major studios reverted back to safer horrors involving ghosts. And the prestigious directors made psychological horrors.

It was the Italians and the low-budget exploitation American films that carried the bloody blades the films of 1960 had handed them. Foreign directors took it further and created what we now call slashers (in Italy, they were giallos). By 1968, the American Production Code had ended. And the bloody gates were open.

This list of the best horror films of the 1960s shows the scattershot genre jumping of acceptability at the time. From the shocking year of 1960 to ghost stories to giallos to psychological terror and parables of distrust, I rounded up to 18, just like many of the ratings boards of the world would create by the end of this decade to signify the proper age (17 in some territories, 18 in others) to watch the horrors of the 1970s.

'Black Sunday' (1960)

Before Mario Bava would direct the earliest identifiable slasher films in Italy, which genre-lovers loving know as giallos, he made this gothic throwback that could easily stand astride the best of Hammer Films’ output of the previous decade. Black Sunday begins with a stunning and horrific opening sequence that would get the film banned in the UK for years, although it is nowhere near as violent as Bava’s films would become less than half a decade later.

In the opening, Princess Asa (Barbara Steele) is convicted of being a witch and has a bulky and spiky satanic mask nailed onto her face by a massive mallet. She’s buried alongside her lover in a crypt. 200 years later, two doctors discover the tomb, are attacked by a bat and blood is spilled on her casket. They curiously pry the mask off of the Satanic Princess’ face and a curse is unleashed, as Asa takes possession of a virginal woman in town (Steele again) and sets out too unleash her revenge.

Black Sunday was Bava’s first great horror and it’s appropriate to see him hone his craft within the confines of a classical horror (pushed a little too far for some) before creating a new cinematic language all his own.

'Eyes Without a Face' (1960)

Georges Franju was one of the creators of the famous French Cinematheque that housed long lost classics and introduced the filmmakers of the French New Wave. He’d worked tirelessly during World War II to find, protect, and move around various film cans from being destroyed. Franju was obviously a lover of the moving image. And in his most beloved film that he himself directed, Eyes Without a Face, the image creates the entire mood.

Franju’s eerie film follows a plastic surgeon that specializes in transplanting living skin tissue from one person to another. When he causes a car accident that disfigures his daughter (Edith Scob), he begins to abduct women and flay their skin, attempting to give his daughter a new face; when it doesn’t work, he has his assistant drop their bodies in the river. Meanwhile, his daughter awaits a new face behind a white mask, eerily ghost-like. When she learns what his father is doing for her, Scob and Franju are shockingly able to show sadness not for herself, but for the victims who her father is trying to graft her, with only eye movement behind an emotionless façade.

'Peeping Tom' (1960)

Audiences were so horrified by Peeping Tom that it was actually pulled from theaters. They felt violated and betrayed because one of the most revered and hopeful of Britain’s directors, Michael Powell (The Red Shoes), had made something perverse and psychotic. He made viewers confront the level of thrill-seeking they hope to get from a moving image by following a smutty photographer/amateur filmmaker (Karl Boehm) who photographs nudie pics for side money, but gets his real thrills from filming women while he stabs them to death with a blade on his tripod.

When the photographer begins to form a friendship with his downstair’s neighbor, he attempts to reform, but his psychosis goes much deeper than thrills and reveals a nefarious experimentation in fear, with his father as the controller and he as the subject. Powell, who always possessed one of the most impressive visual eyes, uses the grainy mouth-open screams of women to communicate to the audience that the act of filmmaking is providing something to voyeurs. There are different levels, sure, like the fellow that Boehm observes shopping for nude photos in says store but says no to purchasing a nudie film. With a picture you retain control of your fantasy. With a motion picture, someone else has control of the imagination and you just watch.

'Psycho' (1960)

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is the big kahuna of this list. The shower murder of our beautiful heroine (Janet Leigh) features 77 camera angles and almost as many cuts (and string shrieks from composer Bernard Herrmann). It’s one of the most perfect moments in all of cinema. And there’s so much to unpack from those three minutes alone; everything in this scene is so close and jarring it gives the affect of visual processing itself, as the eye funnels the violence down the drain of our own mind.

But as standalone amazing that sequence is, the rest of the film is equally terrific. One of Hitchock’s most amazing feats that he pulls of with Psycho is creating fully formed characters whom he knew he was going to dispatch halfway through or introduce halfway through. It’s something that most horror films don’t have the gall to attempt: to humanize the victim that won’t make it and simultaneously their relationship with the killer. Our heroes and heroines and villains don’t need to be with us every step of the way.

Psycho is a pure flex of the film muscle. Like Powell, Hitchcock understands that the very act of filmmaking is presenting something to voyeurs and he begins by putting his actress in a bra but then later shows the disturbed hotel manager (Anthony Perkins) looking through a hole at her; Hitchcock knows that the audience will recoil, even though he’s repeating the same anti-Production Code act that the very audience did at the start of the movie, which many in the audience likely enjoyed.

'The Innocents' (1961)

The Innocents is one of the most evocatively shot horror films of all time. Both narratively and visually, this ghost tale is about what we do in the shadows. The black and white cinematography makes candle flickers unpredictable, the space under a doorway extra creepy, but Jack Clayton also uses it to highlight the black-and-white approach of right and wrong adherence in religion that makes people go mad. In The Innocents, we’re never sure if the ghosts are real or are a manifestation of a mind that’s shaming itself for losing innocence.

Deborah Kerr plays a governess who believes that the grounds of the house—where she cares for two orphaned children—are haunted, perhaps even working to possess the children. Her first inkling of a haunting comes after she hears the children’s uncle (a lascivious Michael Redgrave) boast of a sexual encounter. There’s further evidence that the previous governess and her brutish lover might have introduced sexuality to the children at a young age. There’s an inkling that Kerr’s governess is so sexually repressed that her desire to take care of children is a substitution for feelings of attraction to their experienced uncle. She sees ghostly spirits, whether they’re there or not, and Clayton and cinematographer Freddie Francis find shadowy dread in every corner. But an undervalued feat is done by screenwriter Truman Capote, who turns a screw on the Henry James novella, The Turning of the Screw, and introduces a locket and photograph at a much earlier point than James’ novella in order to turn the screw on the audience and call everything into question.

'The Birds' (1963)

The Birds was the most difficult film (wrangling all those birds and using very primitive technology) to make for Alfred Hitchcock. It doesn’t stand up as well now in comparison to many of his other classics, simply because the technological advancements years later makes us aware that in most attack scenes the birds diving are overlaid over the actors reacting in a different shot. It also doesn’t have a satisfying ending or an emotional through line to pull us through all the attacks. The Birds might not have aged as flawlessly as many of the Master’s films, but he still stages many masterful moments.

What The Birds does have is an amazing home invasion section that greatly influenced every zombie or home invasion film that would come later. The birds, which have begun attacking humans for no reason and seem to have a particular bone to peck with a socialite (Tippi Hedren) who was recently in court for her racy behavior, swarm the house that holds her inside. They peck through the walls, their beaks poking through like a Whack-a-Mole game. Her love interest (Robert Taylor) has to board the doors and nail furniture in front of weak spots.

The Birds shows all the survival tactics that we now know from zombie films and it also features the fatalist moment where the heroine goes upstairs. Always stay downstairs.

'The Haunting' (1963)

Many of the great ghost stories embrace our skepticism of whether our protagonists are actually haunted by ghosts or just losing their minds to unexplained sounds, forgotten placements of objects, and their mind fills in the blanks in ways that then present spooky visages. Robert Wise’s The Haunting presents this as a dare. There’s a spooky mansion with handed down tales of hauntings, death and insanity. Someone’s about to inherit the house, though, so they pay to send researchers of the paranormal to stay in the house and provide him explanations for the haunting.

Is the house on the hill actually haunted? Or does being told that it’s haunted play tricks on everyone inside? Some retain skepticism. Others go mad. It seems that if the house wants anything, it’s both of these responses, because both skepticism and belief will continue to send people there for answers.

'Blood and Black Lace' (1964)

Mario Bava changed horror forever with Blood and Black Lace. Already a horror maestro, Bava kicked off the giallo genre (Italian bloodletters) with highly stylized and gruesome kills, interesting point of view shots that withheld the killer’s identity while also gave up close vantage points for slicing and strangling, and set colors that were as bright as the fake red blood that gushed from wounds.

Blood and Black Lace’s setting is a fashion house where models are being murdered. In what will become a giallo staple, the killer wears black gloves, a black hat and a black trench coat with a switchblade and wires in their pockets. In a devilish visage, Bava stages one of the hunts in a room full of mannequins, with the model dispatched as quickly as the industry itself gets rid of those bodies itself; with witnesses as mute and faceless to the industry’s practices as the mannequins are to the murders.

'Hush... Hush, Sweet Charlotte' (1964)

Robert Aldrich made diva camp before that was even a known thing. Sunset Boulevard was the first film to truly make use of a faded Hollywood star, but there it presented the older Hollywood star as having a diseased wish for continued applause. In 1962, Aldrich’s What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? allowed Bette Davis and Joan Crawford to go full on deranged as two sisters—who used to be stars—torture each other inside an unassuming apartment building.

Although, Baby Jane does have horror elements (Crawford is both roped to a bed and starved when she’s not being served rats for dinner), Aldrich’s Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte gets the nod here. Structurally, the stories are very similar. They both begin with a violent act. And they both revolve around a dysfunctional and brash Bette Davis and a family secret kept by another relative (here, Olivia de Havilland subs for Crawford, who was originally cast, but dropped out, probably aware that Davis once again had the juicier role; although de Havilland perhaps knows better how to step back from Davis and not try and match her, but be more secretive in her performance). But while Baby Jane had shrilly-laudable camp moments, Charlotte makes everything more refined and gothic. The meat cleaver murder of Bruce Dern is certainly one of the most graphic moments in film of that time period. He loses a limb before another blow is delivered. The blood is on Charlotte’s dress, but because she’s a teenager to a respected family, she’s basically just sentenced to live in her southern mansion and not bother anyone. When we met Charlotte as an adult (Davis) she’s aiming a shotgun at the developers who are trying to run a highway through her land, and she’s having night visits from the ghosts of men who’ve been murdered in the house, and fresh blood begins appearing on her dresses again.

Baby Jane was a hoot. Sweet Charlotte is more Grand Guignol, with magnolia tree shadows, ghosts, and severed limbs. One is camp, the other is high camp. Appropriately enough, the term “camp” first came into fruition in 1964, in an essay by Susan Sontag.

'Repulsion' (1965)

Roman Polanski’s first English-language film follows a fractured woman who fears penetration from every man she encounters. It’s also a film that breaks into new fractures due to the grotesque and crooked turns in Polanski’s personal life that came later (the brainwashed cult murder of his wife and child, and his drugged rape of a teenager). There’s a sense in Repulsion that no one has control of his or her mind. Certainly Carole (Catherine Deneuve) has no control over her fear of sex (with small hints of previous abuse). She has nightmares of hands breaking through the wall and groping her and thinks of men cornering her and raping her. She's paralyzed and near mute by these visions.

There’s also a sense that the men can’t help it either, not necessarily that all men could potentially rape, but they don’t know how to not be turned on by someone as beautiful as Deneuve. Polanski films most of her psychological breakdowns while she wears a near sheer nightie. I don’t think it’s meant to be gratuitous, but perhaps Polanski feels that he should provide evidence that she should indeed be afraid. Even when she’s had a complete meltdown and requires help off the floor, the manor in which she’s cradled by the man who helps her is filmed like a successful conquest of carrying a virgin into the bedroom for the first time. Repulsion is a fantastic psychological study that’s perhaps even more psychological and, at times, repulsive—now that we know of Polanski’s fractured existence.

'Kill Baby, Kill!' (1966)

Mario Bava’s Kill Baby, Kill! is the Citizen Kane of giallos. You can see and hear the influence on Dario Argento and other stylized blood splatterers everywhere. There’s Bava’s color palette of bright greens and reds, making every spooky place for a potential murder look like a church’s stained glass window that’s about to get stained red. There’s a soundtrack full of ghostly sighs and gasps that would later creep into Goblin’s electro-scores. And then there’s Bava’s inventive camera zooms on spiral staircases and a camera point-of-view from a swinging swing set. These tropes have fingerprints all over the best Italian shockers that would be released for the next 30 years. Perhaps if it had a better title, Kill Baby, Kill! would rightfully be mentioned by all as one of the all-time great horror films.

In Kill Baby, Kill! the ghost of a girl who was trampled by horses haunts a Transylvanian town. She appears in a dress, bouncing a ball, and if eye contact is made, mind control and a horrible death soon follow. There are misty graveyards, thick cobwebs, throat slashes, pierced temples and impalements; it would’ve no doubt shocked in 1966. 50 years later, the uniqueness of Bava’s camera choices still resonate and inspire the type of soft gasps and sighs that’d soon pepper the soundscapes of shock cinema.

'Seconds' (1966)

John Frankenheimer’s Seconds is an anti-mainstream/anti-counterculture parable about aging that’s more of a thriller than a horror, but it certainly has major horror elements. There’s a phone call from a dead man, a secret society that’s housed underneath a slaughterhouse, and multiple forced surgeries and concealed identities from bandages. On top of that, the great cinematographer James Wong Howe utilizes many woozy, fish-eye lens camera set-ups to give an immense feeling of dread, make you question whether what you’re seeing is real, and could be argued that it greatly influenced the devil’s rape ceremony in Rosemary’s Baby two years later.

John Randolph is a bored banker who receives a phone call from a man he thought was dead, but knows the type of things that only the man he claims to be would actually know. The dead man’s voice said that there’s a company that will fake your death and give you a new body and identity and fold you into a community of people who are living their second chance at life (what he doesn’t say is that he’s stuck in an eternal waiting room trying to go back to the life he left behind, but he must recruit a new body in order to leave). There’s no backing out, as the company also drugs and films their subjects doing nasty deeds for blackmail purposes. Thus Randolph becomes a younger looking Rock Hudson whose second chance involves wine-stomping orgies, sure, but he has no free will and no ability to escape.

'Spider Baby' (1967)

While there are touches of camp and exploitation on this list, Spider Baby is the best true American exploitation horror film of the decade (with an all knowing hat tip to Hershel Gordon Lewis, who pioneered gore effects during this decade, but his films never did much more than splatter blood and sputter dialogue). It’s got a credit theme song about a cannibal orgy where everyone is “sure to wind up in somebody’s tummy” after all. Spider Baby is about a very caring caretaker (Lon Chaney) who looks after a house of inbred young adults. He attempts to keep them from meeting any strangers because they have a degenerative brain disease that makes them have the cognizant brain of a five year old, except with the desire to kill and eat anyone who isn’t family. The extended family has left them to die out in a house to remove the gene from their bloodline, but of course, some people come looking to appraise the value of the house and “playtime” begins.

Jack Hill’s (Coffy) film is too odd for the mainstream but not violent enough for gore-heads. But if you take elements of Freaks, Two Thousand Maniacs and add a lingerie chase scene and the uncomfortable adult-bodied seduction techniques of women who are constantly described as “children”, then you’ve got a nice web of exploitation fun here. Added cult bonus: Sig Haig (The Devil’s Rejects) is one of the inbred “children”.

'Kuroneko' (1968)

You’ll frequently find Masaki Kobayashi’s hypnotic tetraptych of supernatural folktales, Kwaidan, on a list of best 60s horror films. It’s poetic. It’s visionary. The music is haunting. But it’s more calmly meditative and moralistic than it is horrific. Instead, Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko (Black Cat) gets the honor to represent Japan’s rise into horror filmmaking of the 60s. It too is poetic, visionary, haunting and moralistic, but it also features more real horror than Kwaidan. A black cat drinks blood, women draw blood from the necks of unsuspecting men, seductive ghosts kill samurais to keep their own souls from entering the gates of hell, and a house that was burned to the grown reappears spectrally. Yep, this is unquestionably a horror film.

Kiwako Taichi and Nobuko Otowa are the ghosts with samurai bloodlust; they also used to be the wife of and mother to a solider (Kichiemon Nakamura). The soldier has been battling away from home for a few years. During that time, his wife and mother are discovered by a band of samurais on their way back to their village; they are raped and burned alive in their house. While their corpses are feasted on by a black cat, their souls make a deal with the devil to remain haunting the woods, killing all samurais; they get close to them through seduction and then drink their blood. The husband, however, is made a samurai after his bravery in battle and his wife and mother have a very difficult choice of what to do with him.

Shindo’s film is a gorgeously shot rebuttal to the overly fawning nature of samurai literature and films. With the exception of the valiant husband, the samurai are shown to be selfish individuals who do not care for the outlying villagers; only their own rank and their own libido matter. It’s not anti-samurai, but anti abuse of power.

'Night of the Living Dead' (1968)

The zombies in George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead are called “ghouls” but nonetheless this is the film that created the movie zombie as we know them: blank, thoughtless creatures who lumber around with vacant stares and barely retain any resembling sense of their humanity. For this reason, the thrill of the movie zombie has generally been in seeing how our heroes with brains dispatch them with great efficiency and cruelty. They’re no longer human, after all.

However, re-watch Romero’s film and try not to escape with having more sympathy for the “ghouls” than most of the humans. The living humans mostly only retain humanity’s weakest learned attributes: prejudice, xenophobia and selfishness. The most selfless non-ghoul we follow (Duane Jones) is famously shot—after valiantly fighting against the ghouls—simply because his skin color triggers a suspicious reaction to the man on the other end of the rifle. But Romero plants many other distrusts of authority motifs throughout Night of the Living Dead. In 1968, recent public opinion on the war of Vietnam and in the police tactics during the Civil Rights movement had shifted to no longer give blanket trust of best intentions to law enforcement, generals and soldiers. They’re human after all, and many humans harbor ill intent to others. Just watch the burial of the once human ghouls who are dragged out by meat hooks and burned in a pile and try not to think of any xenophobic war or a horrific systemic view of the “other”.

'Rosemary's Baby' (1968)

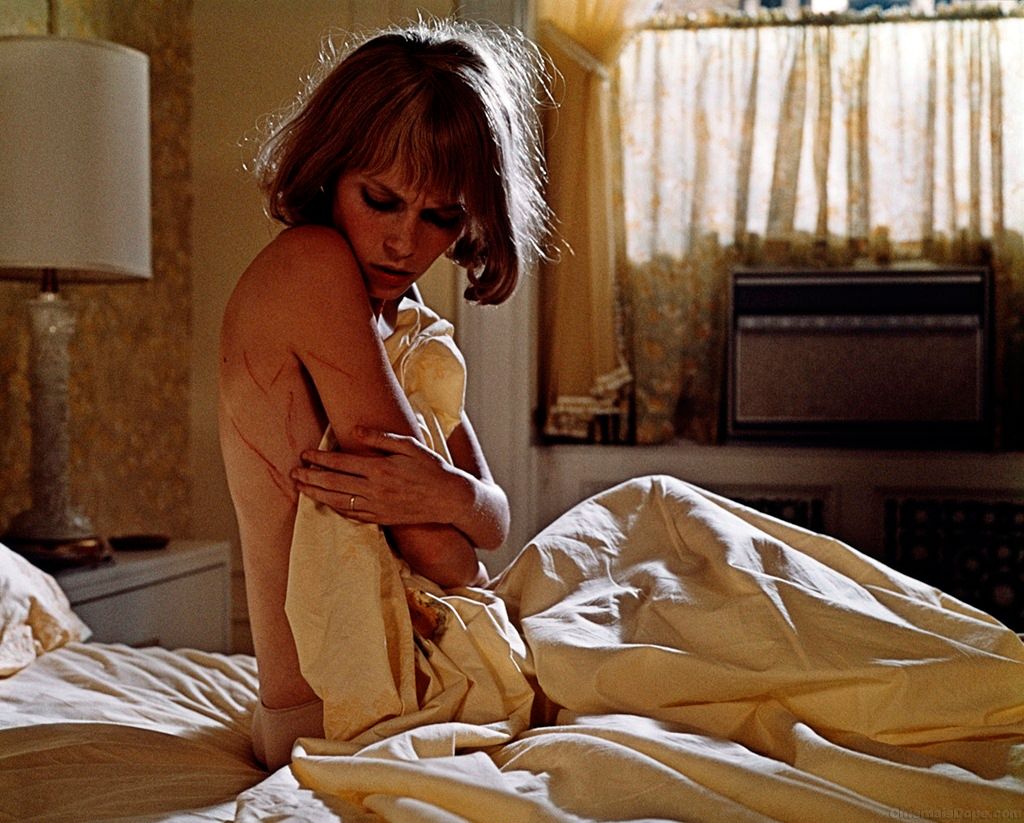

For me, Rosemary’s Baby is the best horror film of all time. It operates so highly on every level. A newlywed couple, Rosemary (Mia Farrow) and Guy (John Cassavetes) appear idyllic when we’re introduced to them as they shop for a new Manhattan apartment. But when there’s a lack in one person there becomes a lack in a relationship. Guy is a struggling actor and Rosemary tells everyone who’ll listen the two plays and commercials that he’s appeared in. This should sound like support, but to Guy it’s a reminder of his perceived failure. In their new apartment building they befriend some old kooks (Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer) down the hall.

In one hellish sequence, Rosemary drifts off to sleep on an bed on water, catches glimpses of Satan climbing atop her while Guy, the neighbors and other creeps watch the demon claw and thrust and not do not assist her as she cries. In the morning, she wakes up nude with claw marks all over her. Her husband says that he decided to impregnate her even though she was asleep because he was in the mood and they’d talked about it. So what if she was “drunk.” Rosemary later thinks that she was raped by the Devil and that Guy promised the Devil's child to their Satanist neighbors to better his career.

Not only is the ceremony one of the most terrifying and transfixing sequences ever committed to film, it's one of cinema’s biggest violations. There’s a violation of trust and body so profound in the ceremony, but it’s further insulted by Guy’s lax cover-up of “I wanted you right then.” The rest of the film shows Rosemary completely unable to have agency for any choice involving her body. Everything is decided by the elders and by the male doctors; even the one she trusts, Dr. Hill (Charles Grodin), who she chose on her own, hands her over to a different doctor because he thinks she’s unstable. Every man silences her and thinks she has no idea what is going on in her body. With many men still feeling fuzzy and woozy (like Rosemary on her drugged bed) about what actually constitutes consent and choice, Rosemary’s Baby is still one of the most terrifying and necessary films ever made.

'Blind Beast' (1969)

Yasuzo Masumura’s Blind Beast does the difficult task of using film to explore the physical sensations of not having sight. It also wrestles with sexual domination, Stockholm’s syndrome, and features bodily dismemberment. It’s a pretty heady exploitation film that’s done very artfully and ultimately serves as a unique pre-cursor of obsessive body modification being used for the purposes of both pleasure and pain that would feature in the wholly unique Tetsuo: Iron Man series.

Blind Beast begins with a doting mother kidnapping a model (Mako Midori) and tossing her into a massive sculpture studio that does not receive light. Inside, her blind son (Eiji Funakoshi) has sculpted the entire space in ode to women’s body parts; a resting spot being between breasts, the space sloping down a clay stomach to another area. He desires a new specimen to learn each part of her body through touch and turn into his most complete work. She resists (and the shift of rape turning into submissiveness, then into seduction, then into enjoyment are murky here, but never played up for titillation) but eventually becomes so in-tuned to his senses that she desires to go blind as well. Together they’ll explore bodies in a different—and more horrifying—way; and morbid fantasies give way to self-destruction.

This is a challenging film that requires some preparation to endure, not for bloodiness, but for its ideas. What’s scary about Blind Beast is less what you see on a basic level, but what you process after the sights are sent to your brain. We see moments of true intimacy and true tortuous perversion and both land with thoughtful immediacy.

'The Honeymoon Killers' (1969)

I’m capping this list with a film that isn’t a pure horror film, but one that enters the genre discussion the same way that something like Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer does. Leonard Kastle’s The Honeymoon Killers was the most naturally shot serial killer film of its time. It features a hammer blow to the head that is not done with an extra close-up shot but is done in a full-body frame, emphasizing the pained reaction from the woman on the receiving end and the “why don’t you just die already” reaction by the woman who delivered it. Just two years after Bonnie & Clyde stunned American audiences with slow motion bullets into bloody wounds, Kastle made a film that doesn’t romanticize the violence as a poetic bloodbath but presents it so matter-of-factly it makes you feel like you’re in the living room watching these “Lonely-hearts Killers” commit murder after murder. It received a positive review from Variety at a showing in 1969, but it went untouched by distributors until the following year. It was banned in many countries until the 1980s, but also has the distinction of being the all-time favorite American film of one of the French New Wave’s biggest names, Francois Truffaut.

The Lonely-hearts Killers (Shirley Stoler and Tony Lo Bianco) met through a newspaper pen-pal service to find love. Ray (Lo Bianco) is a con man who earns the woman’s trust, gets free lodging, promises marriage, and then murders them. He doesn’t murder Martha (Stoler), though. And the two pose as brother and sister while he picks up new victims and she gets jealous from seeing the other woman beam in his presence. They kill together, but Martha begins to kill more brutally and passionately, trying to end her entrapment and carry on with the man she now loves.

Unlike the giallos that preceded it or the 70s slashers that would follow, The Honeymoon Killers doesn’t go for flair. Indeed the budget was so small that the originally hired director, Martin Scorsese (!!), was fired because he spent too much time shooting moody insert shots that slowed down the production (like shots of garbage left at the beach). Because the budget didn’t allow any extra days whatsoever, the screenwriter, Kastle, stepped up to finish and direct his only film. It’s shot almost documentary like, with uneven sound, and the mis-en-scene of a beginner. It’s only his (magnificent) use of Gustav Mahler’s pre-existing symphonies that remind you you’re not watching some illicit home movie. The Honeymoon Killers is a rare novice film that feels revolutionary.