M. Night Shyamalan is one of our most curious and deservedly debated filmmakers working today. After breaking through with 1999's The Sixth Sense, Shyamalan went on a precocious, meteoric rise to the top. His talents were celebrated, his craft compared to masters like Alfred Hitchcock and Steven Spielberg, his name calcified into a brand. "An M. Night Shyamalan film" carried meaning and weight, especially at its caboose; Shyamalan's most resonant (if reductive) legacy became his utilization of the ending plot twist, a canny bit of writing trickery that recontextualized everything we saw before.

Then, the brand's luster faded. Your mileage may vary as to which film signified the beginning of the end for Shyamalan's original period of acclaim, but once he started producing critically and culturally derided work in the 2000s, he did not stop for some time. While this period is full of genuine experimentation for the director — moving away from the horror genre, adapting material, working with other screenwriters, trying his hand at big-budget blockbuster cinema — it's also full of genuine strife. "An M. Night Shyamalan film" began to carry a stigma; I remember distinctly seeing the trailer for Devil, a 2010 film that Shyamalan produced but did not direct, and hearing raucous, disgusted laughter explode when his name splashed across the screen.

Then, the plot twist. Starting with 2015's The Visit, Shyamalan found a kind of re-renaissance. His budgets became lower, his premises became tighter, and his love of genre became purified. The Sixth Sense's Shyamalan was still the auteur behind these intentional films, but in some crucial ways, he seemed different. Moreover, he and his work seemed changed.

This metatextual character arc, this directorial rise-fall-rise story structure makes Shyamalan a particularly fascinating filmmaker. While just about every cinephile can agree that, say, Paul Thomas Anderson has been a very good filmmaker throughout his career, Shyamalan tends to prompt more debate on metrics both micro and macro. I have long admired (and at times apologized for) the man's work. He's a visual architect of the highest order, his screenplays blend thrills and heart in powerfully emotional ways, and even his most venomously regarded films are too strange, too idiosyncratic, too human to simply disregard.

In honor of Shyamalan's latest, Knock at the Cabin, here are all of his directorial works ranked from worst to best.

15. The Last Airbender

Okay, well, here's the one Shyamalan film you can disregard wholesale. The Last Airbender, a big-budget adaptation of the beloved cartoon Avatar: The Last Airbender (blame one Mr. James Cameron for the first word's removal), is ugly, sloppy, and anonymous. It's poorly lit, choppily edited, and problematically cast. Desperate voiceover tries to smooth together and over key plot points, resulting in an incoherent mish-mash of narrative soup. Newcomers to this universe will leave feeling confused; fans will leave feeling betrayed. For a guy who tends to control every single aspect of his films, sometimes for the worse, Shyamalan let this one slip away into anonymous nothingness.

14. Wide Awake

Wide Awake is kind of a pre-genre trial run for many of Shyamalan's pet themes he'd explore in later, more successful films. Hooky premises culminating in a twist; precocious, wounded children; Catholic-filtered ruminations on faith and betrayal; a chapter title that literally reads "signs" — Wide Awake, if nothing else, is proof positive that Shyamalan has known what he wants to talk about since the very beginning (released in 1998, Wide Awake is Shyamalan's second feature film, and the last one before he became "M. Night Shyamalan").

But without the later-found skeleton of horror, Wide Awake plays too loosely and inconsistently to make any kind of mark other than befuddlement. The tale of young Joshua A. Beal (Joseph Cross) and his quest to literally talk to God after the traumatizing death of his grandfather (Robert Loggia) is told with whiplash-inducing tonal shifts. In its luxuriously lit (but disappointingly mediocre) compositions and grandstanding orchestral score, Wide Awake insists upon being reckoned with as a casual, even zany entry into the pantheon of '90s family comedies — Rosie O'Donnell as an eccentric, baseball-loving nun just nails the point home. And yet, there's too much raw nerve, and even abject emotional shittiness at the center of the film to make this feel like a unified set of creative choices. Joshua is downright rude to a classmate who just wants to play with him — yet easily, sappily makes amends with his own bully. Tears flow freely, from Joshua, from his grandfather, from everyone written with their heart barely hidden below their sleeve — but these moments of gripping catharsis are immediately neutered by over-easy, self-satisfied jokes. Adult figures patiently, powerfully, even sorrowfully explain to Joshua that faith doesn't come from one single event of proof — and then the film's twist gives him one, negating the point of this entire story of discovery.

It's a confusing roller-coaster of a watch. And yet I cannot deny its literally tear-jerking moments of power, its times that prove Shyamalan is willing to delve deeper into the psychological makeup of pain, family, and exultation than the average populist filmmaker. Wide Awake is Shyamalan at his most experimental, his most "throw everything against the wall and see what sticks." It's inherently smeary, but never boring.

13. After Earth

After Earth has a contemptible 11% on Rotten Tomatoes — and I'm the only one brave enough to say "that's a little unfair!"

Unfortunately, one of After Earth's largest problems is smack-dab in the center. Jaden Smith, now one of our most engaging and altruistic musical performers, is our vehicle for the picture's dystopian action-sci-fi thrills, and he simply does not have the mileage to pull it off. His take on Kitai is abrasively one-note, unintentionally immature, and whiny — and we're supposed to spend the majority of the film following his solo journey of discovery! Yikes! Shyamalan has proven himself time and time again to be a master of directing child actors; here, the train falls off the tracks and then some.

But the other components of After Earth, even in their problematic, Scientology-adjacent messages and themes, do not merit such a wide-reaching attitude of loathing; maybe just of blandness and forgettability. Will Smith, as the very unfortunately named Cypher Raige, gives a refreshingly subdued, seething performance of repression — in a superior Shyamalan film, he would be the director's ideal protagonist that gets his faith restored; here, he seems eternally stuck and even bored. Shyamalan's understanding of visual storytelling, of "the set-piece," remains sturdy and more than capable — in a superior one of his films, this command of craft would rise above expectations instead of barely, gloomily touching them. Grief, fear, and danger permeate the atmosphere appealingly, especially in Sophie Okonedo's melancholy performance as the Raige matriarch (again, very unfortunately named). But in a superior Shyamalan film, these thick elements would explode in a satisfying arc of profound change. Here, despite his efforts, their inertness just drags everything down.

My gut says that, at this point in Shyamalan's career (2013), people would've derided just about anything he put out as an appealingly schadenfreude-laden move surrounding his narrative. My heart says that it's really not that bad. But my brain can't help but be a little bored by the whole conversation.

12. Glass

My expectations for Glass were sky-high. But as the film lurched on, they slowly began to shatter.

It's the surprise threequel to a superhero franchise I didn't understand Shyamalan was building; the grandest and most metatextual plot twist of them all. It's the cumulative catharsis of three powerful characters played by three powerful movie stars: Bruce Willis, Samuel L. Jackson, and James McAvoy. In their separate, preceding films, Unbreakable and Split, we see their origin stories, their battles with repression, their discoveries of who they really are, their unchained freedom. In this, the Avengers: Endgame of the M. Night Shyamalan Cinematic Universe (MNSCU), we finally see them collide, see their final fates, see pure behaviors defined by heroism and villainy, all unburdened by any need for setup. Except...

It's my fault, I know it is. Glass is almost perversely, solely interested in setup, in the neutering of any catharsis, in sitting still and talk, talk, talking about every little thing instead of act, act, acting. It's a weirdly plot-driven picture, with all three leading characters, characters with so much pre-established intrigue about them, becoming softened and squished into a sort of diet soda version of whoever they used to be to slide through the film's still creaky machinations. It's like if the last moments of Psycho, where a psychiatrist plainly and calmly states why Norman Bates behaves the way he does, were stretched out into feature-length. Its plot twist is nonsensical, frustrating, inadvertently silly, and seemingly setting up some other kind of unexplored universe instead of closing this one up in a satisfying loop. But still...

Every single piece of Glass feels placed carefully by Shyamalan. Visually, it's among the most splendid films of his career; he gives himself permission to go wild in the wide frame, to pack each composition with stylized color temperatures, to stage sequences in bravura long takes, to edit everything together with cause and effect. And if you look closer at the pieces of "creaky screenwriting," you start to see intentions and patterns and statements emerge. "Talking about these superheroes" as a primary movie-mover is so pervasive that it becomes a feature, not a bug. In-universe news reports boast of a giant building being in downtown Philadelphia, with the newscaster even calling it a "marvel." You'd imagine Shyamalan's setting us up for a big showdown there, right? Instead, the final confrontation takes place literally feet away from the rest of the movie's cramped asylum location, and ends in bug nuts anticlimax for all parties involved. It's deliberate provocation, discussion, and dissection of what we expect out of superhero stories. It's Shyamalan making these strange choices, almost making his movie "less of a good movie" for his greater, more mysterious goals. Shyamalan smuggled a superhero film into a prestige thriller with Unbreakable, then smuggled an Unbreakable sequel into a trashy horror film with Split. Maybe with Glass, Shyamalan smuggled a low-budget 1960s B-movie satire into a big-budget 2010s superhero movie? Less Shazam, more Shock Corridor?

As much as I disliked the film, the thought keeps gnawing away at my brain: Maybe I'm wrong. Maybe Shyamalan's operating on another wavelength that I just need to jump on. Maybe Glass is a stealthy, deconstructive masterpiece. Or maybe it's just bad. But it's stuck in my craw, alright, like my brain stepped on a piece of... you get it.

11. Praying With Anger

Shyamalan's first feature film, Praying With Anger, stars the man himself as Dev Raman, an Indian-American student who travels to India, learns about the oft-fraught differences between these two cultures, and tries to find a constructive place to put all of his negative, resentful emotions. In some ways it's Shyamalan's simplest and most explicitly autobiographical film to date, perhaps a given since he cast himself as our leading man going through these changes and strifes. But in its narrative simplicity comes its biggest set of issues: The screenplay is so on-the-nose, so "telling not showing," and so driven by emotional whims that it plays like an unfettered diary, a therapy session, or vent sesh. But despite the film's herky-jerky, episodic-feeling digressions, Shyamalan's level of authorial control — or should I say ego? — runs out of the gate with a sense of undue confidence that further hamstrings the picture. His Dev talks about wanting to be a writer who writes about important things. His Dev has the correct take on Shakespeare as a populist entertainer who smuggles in important things for his adoring but common crowd. His Dev is our idiosyncratic, relatable, struggling, budding genius whose biggest problems are that he's too profoundly emotional, dammit!

At times, Shyamalan knows he's painting a target on his own back. His Dev is often humbled and beaten, sometimes literally. His Dev is a stranger in what's supposed to be his homeland. His Dev feels so much and doesn't understand why no one around him will let him. These are big, broad, relatable emotions, and when Shyamalan gives them the space to be explored and discovered, they can really hit us in the heart, at times turning Praying With Anger into an effective short story collection. And throughout the film, Shyamalan's work as a visual stylist is beyond impressive; swathed in golden hues and shadows, the frames he finds are simply gorgeous, giving the work the qualities of a lucid dream, a waking tidal wave. It's not hard to find the raw materials of a great filmmaker in Praying With Anger, but it feels particularly hard for this filmmaker to know what to do with them. "Do you understand anything?" one character asks Shyamalan's Dev. "Not really," he responds. "But I can see the emotion." It's not quite good enough, but it's a promising start.

10. Lady in the Water

Lady in the Water doesn't make a lick of sense. It's a bonkers, silly screwball comedy full of eccentric characters crossed with a deadly serious grown-up fairy tale full of earnest stares. It's full of odd mythology-building and fantastical terms to quickly learn and cram, but still stubbornly stuck in a need to feel grounded and "real." It's beyond derisive, even cartoonishly so, about certain members of the arts — Bob Balaban plays an annoying, nebbish film critic who prods his human companions and self-awarely-but-wrongly guesses what will happen based on movie tropes — while also being beyond reverent, even cartoonishly so, about others — Shyamalan casts himself as a writer so important that his new book will inspire the next great leader and get him assassinated, and the titular lady in the water (Bryce Dallas Howard) is literally named "Story" and must inspire Shyamalan's genius. Among this all, Paul Giamatti tries his best.

Lady in the Water is, thus, an exhausting watch, full of unchecked hubris, 9000 competing ideas and tones, and a general feeling of building the train tracks while the train plows full speed ahead. But if you allow yourself to be submerged in all of this, to let Shyamalan's tides carry you, to laugh both with and at the strange, misguided confidence of the picture — or, more simply, if you're a fan of "bad cinema" — you might find Lady in the Water to be an entertaining, unique roller-coaster ride. It makes me scream and shout and wonder if the whole thing is gonna fly off the rails. But Lady in the Water exists in mid-air from the jump, unbound by mere mortals' conceptions of "rails," "tracks," or "traditional story and filmmaking structure." If Praying With Anger is Shyamalan's unchecked ego, Lady in the Water is Shyamalan's unchecked id. And ego. And superego. And all the other ideas any philosopher and/or psychologist has ever had. I'm saying it's weird!

9. The Happening

Speaking of being a fan of bad cinema: Most of my favorite entries in the genre attain their campy pleasures and intrigue by an inherent tension between a filmmaker's desires and abilities. Movies like The Room become classics because the artists involved want desperately for their work to achieve greatness, but they do not possess the control to hit those benchmarks. In that reach, the grasping becomes the appeal.

This is not the case in The Happening, which I would argue belongs in the new canon of Perfect Bad Cinema. Shyamalan is a case study of an artist who demands and achieves near-total control. His visual constructions are regimented, his screenplays a series of falling dominoes, he casts himself in just about every film — he needs an M. Night Shyamalan film to be "an M. Night Shyamalan film."

Nothing about The Happening feels accidental. Its lead actors, Mark Wahlberg and Zooey Deschanel, give aggressively inhuman performances. Every supporting character is gifted ("gifted") with a single-mindedly defining quirk: An obsession with hot dogs, a need to filter everything through statistics, a psychopathic paranoia about lemon drink. Comedy — intentional comedy, I think — queasily permeates every action and reaction, no matter how traditionally morbid or horrific it would be in another Shyamalan film, snapping any intent of tension in half. DP Tak Fujimoto, a regular Shyamalan collaborator, shoves the camera tightly into everyone's face, resulting in a look full of exaggeration, distortion, and alienation. One key action-horror set piece comes from an attempt to literally outrun the wind.

Every choice in The Happening feels calculated, placed, and wholly designed to be wholly off. It feels like a '50s B-movie about humans made by aliens. It feels like Shyamalan playing a cosmic, stone-faced joke. It's a movie I re-watch every year and find something new to obsess over. It's so, so bad because it wants to be, somehow making it so, so good.

8. Old

Old puts an eccentric group of characters on a beach where people rapidly age, and lets 'em rip. This is in some ways a spiritual sequel to The Happening — something high-concept is "happening" to a group of eccentric characters defined in archetypes (to the point where one character meets people by asking them bluntly what their occupations are; handy exposition, that), our leading characters, Gael García Bernal and Vicky Krieps, have vague marital strife looming over them, and a sickly sense of humor, wavering between intentional and unintentional, pervades the entire enterprise.

But this is The Happening by way of the guy who made The Visit, Split, and Glass. Which is to say: It is crafted beautifully within an inch of its life. It contains some of the gnarliest, most upsetting imagery and sequences Shyamalan has ever committed to film (how in the heck did this skirt by with a PG-13?). It allows its gifted (and inherently always changing) ensemble cast the breathing room to find nuance and depth in their characters, with Rufus Sewell in particular giving a horrific, yet oddly casual, scene-stealing performance. DP Mike Gioulakis, Shyamalan's go-to since Split, uses every inch of the 2.4:1 frame with elan and glee, swirling our characters in nightmares of negative space, apprehension, and the crystallization of constantly moving forward.

For a director so concerned with control, Old feels satisfyingly and uniquely "free." From the real-time (haha) narrative to the harsh sun-noir daylight to the fact that it doesn't take place in Philadelphia, Old feels like a guy shaking off something that's been holding him back for some time. It's a raucous crowd-pleaser and crowd-alienator, a film that shifts every second and discomforts every way, a fearless flick that simultaneously, kinetically sets up and tramples sandcastles boldly, triumphantly.

7. Knock at the Cabin

Sometimes, it's better for Shyamalan to keep things simple. In Knock at the Cabin, an adaptation of Paul G. Tremblay's novel, The Cabin at the End of the World, Shyamalan is left to one location, a cast of seven characters, and the implication that what happens in this house will alter the rest of the world. It gives Shyamalan both the massive stakes that he looks for in films like The Happening or Signs, but with a restraint that allows him to focus on the character dynamics that he often handles quite well.

With Knock at the Cabin, Shyamalan is able to explore some of his favorite topics, like faith and climate change, but on a smaller scale that plays to his strengths of horror within a confined space, and dynamic performances that keep the audience on the edge of their seats. Stealing the show here is Dave Bautista as Leonard, who along with his associates (played by Nikki Amura-Bird, Abby Quinn, and a scumbag Rupert Grint) must force a family (Jonathan Groff, Ben Aldridge, and Kristen Cui) to decide which member they will sacrifice to save the world. Bautista is at his all-time best here, knowing the horrible things he has to do, while we can tell on his face that he's regretting nearly every single action he makes.

While Shyamalan is often known for—and made fun of—his reliance on twists, Knock at the Cabin is Shyamalan proving he can make a solid, tense, and engaging thriller without any tricks up his sleeve. — Ross Bonaime

6. The Visit

The Visit is Shyamalan stripped to the bone, but it is still very much Shyamalan; in fact, the sparseness of the film makes the filmmaker's idiosyncracies pop even harder. Many of Shyamalan's horror works feel indebted more to the past than to their contemporaries, but in this 2015, he puts on the modern suit of "low-budget found footage," takes it for a spin, and finds some surprising new wrinkles along the way.

It's often a nasty little picture, with our central figures of tension, Nana and Pop-Pop (Deanna Dunagan and Peter McRobbie having a ton of fun), communicating some ruthlessly vivid ideas on the horrors of aging, and that razor-thin line between the unfamiliar and the safe. Some of Shyamalan's scares are so blunt they're almost satirical, especially the playful-but-raucous jump scares Nana gives our set up cameras. But some of them are so unexpected and vile — especially one involving "a diaper" — that they immediately stick to your craw as feeling like nothing you've ever seen. And The Visit's twist just might be the best, or at least the purely scariest of Shyamalan's career; it is a sincere moment of disquiet and fearful realization played perfectly by its participants, especially Kathryn Hahn.

Despite this new zone of working for Shyamalan, his previously established themes and, thankfully, his heart remain central to his aims and goals. Our leading characters, siblings Becca and Tyler (Olivia DeJonge and Ed Oxenbould), have a genuine love and affection for each other that's infectious, and the two performers are strong enough to carry some of Shyamalan's typically overwritten, precocious dialogue. The filmmaker is onto something about how this younger generation is so comfortable communicating via screens, but he also tracks this newfangled comfort to his oldfangled obsessions with the power of storytelling itself, making this somehow more autobiographical and revealing than, say, Praying With Anger. And the film's denouement, despite the preceding nastiness, is full of warmth and complication in equal measure. Quite the magic trick, The Visit is.

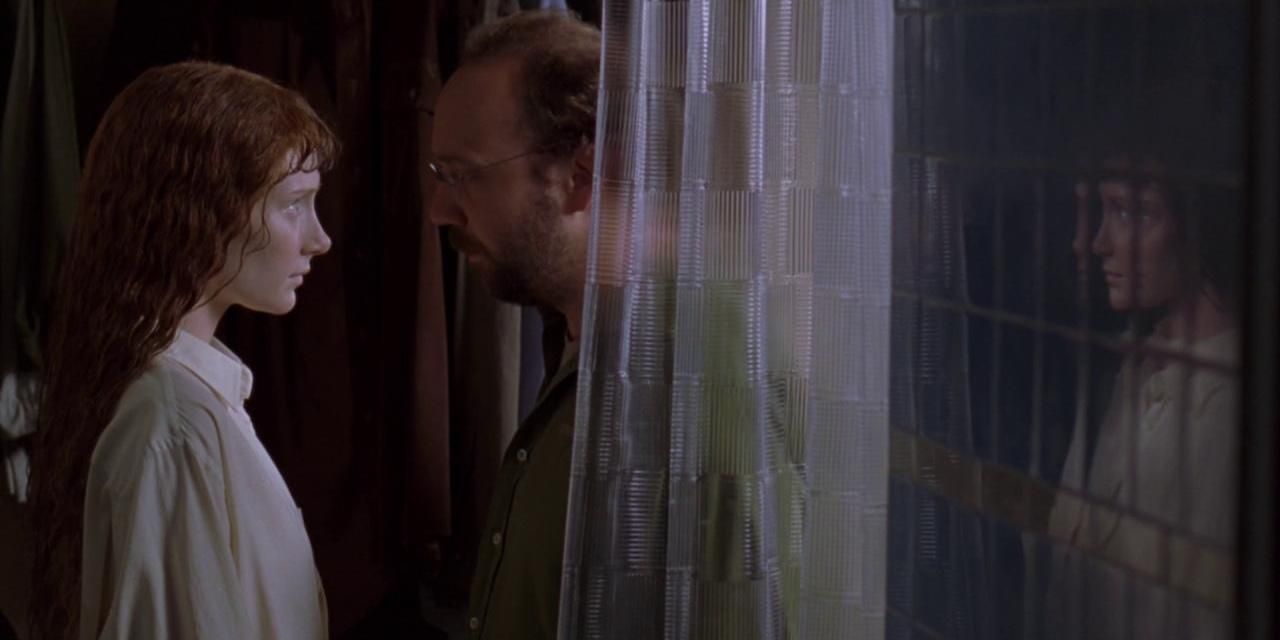

5. The Village

The Village is dummy thicc. The inhabitants of its sequestered, titular world are physically racked with pain, some kind of gnawing guilt, and some kind of unspeakable trauma. You can feel these characters and performers (Joaquin Phoenix, Bryce Dallas Howard, William Hurt, a jaw-dropping-and-not-in-a-great-way Adrien Brody) submerge themselves in this thickness, eager and willing to slow things down, to luxuriate in the pain. Not only does this give the film a sense of classical timelessness — a quality Shyamalan is often after — but it gives its big twist, so derided by critics, a sense of potent irony that radiates even within the metatextual elements, the filmmaking and acting styles themselves.

It's a clever film, which Shyamalan films often are. But unlike his lesser work, I don't get the sense of smugness, of "look at the trick I'm pulling off." It's too slow-moving and, frankly, depressed to allow for such expressions of confidence, and it's all to the film's benefit. Yes, there are sharp-jawed monsters that invade this village and try to gobble people up. But the real horrors go deeper, psychoanalyzing how us pitiable humans deal with the pitiable struggles and traumas of life, only causing more trauma and grief in our stead. Heavy, heavy stuff.

Plus, like, Roger Deakins is so good at being a cinematographer. Dummy good.

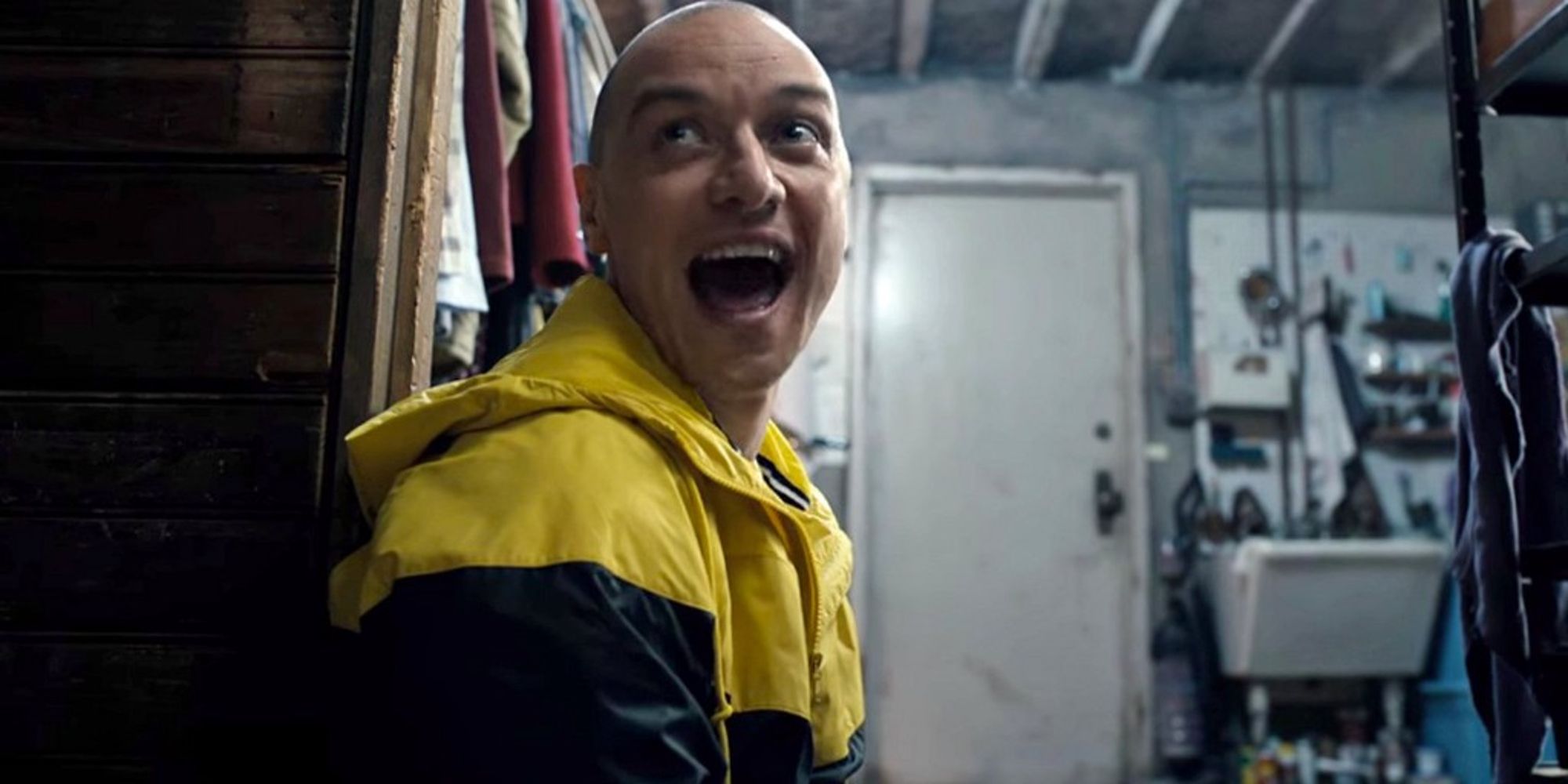

4. Split

Split is, appropriately, a film of splintered extremes. It's one of Shyamalan's most cramped, contained, claustrophobic films, zeroing in with severe focus on the story of a man with split personalities (James McAvoy), the supernatural beast bursting inside of him, and the victim trying to save herself (Anya Taylor-Joy). The depictions of horror feel raw, unnerving, and mean-spirited in a way Shyamalan had never dared tiptoed into before; here, eschewing any subtlety, he pounces on the material with controlled ferocity. Shyamalan's visual constructions, normally rife with formal intention and patience, feel unhinged and purposefully invasive; he and DP Gioulakis distort faces, play with spaces, and generally zag when you expect them to zig. It's a relentless thrill ride, a jolting, abrasive picture that commits hard to its ideas until they fall off the cliff, relishing in your screams as you go down.

But Split also presents one of the realest-feeling protagonist arcs in any of Shyamalan's films, one that personally affected me in a way I didn't know I needed to see, one that makes a conversely giant point about humanity. To call the journey of Casey (Taylor-Joy) "sensitive" would be inaccurate, and not Shyamalan's point. In flashback scenes of distress and menace, Shyamalan shows that Casey was methodically and ritualistically abused by her uncle (Brad William Henke, terrifying), leading to her current state of self-isolation and self-harm. But, these traumas also make her capable, knowledgeable, and a survivalist — a truth about her even McAvoy's monstrous Beast can acknowledge in a final-act conversation that's as illuminating as it is harrowing.

Shyamalan has a tendency to take the themes of "everything happens for a reason" too far; here, he runs close to the risk of arguing that "it's good" these traumas happened to her because they ultimately "helped her" or "made her special." But in this distinction, thankfully, nuance and restraint are shown. It's not okay that trauma happens to someone. But it is okay to be proud of oneself for surviving trauma. It's okay to take steps toward change. And it's more than okay to face these issues head-on, to no longer bury them but to confront them. In Split, Shyamalan hits the goal he's been searching for his entire career with a flexing level of aplomb: The genre picture that leads to the greater truth.

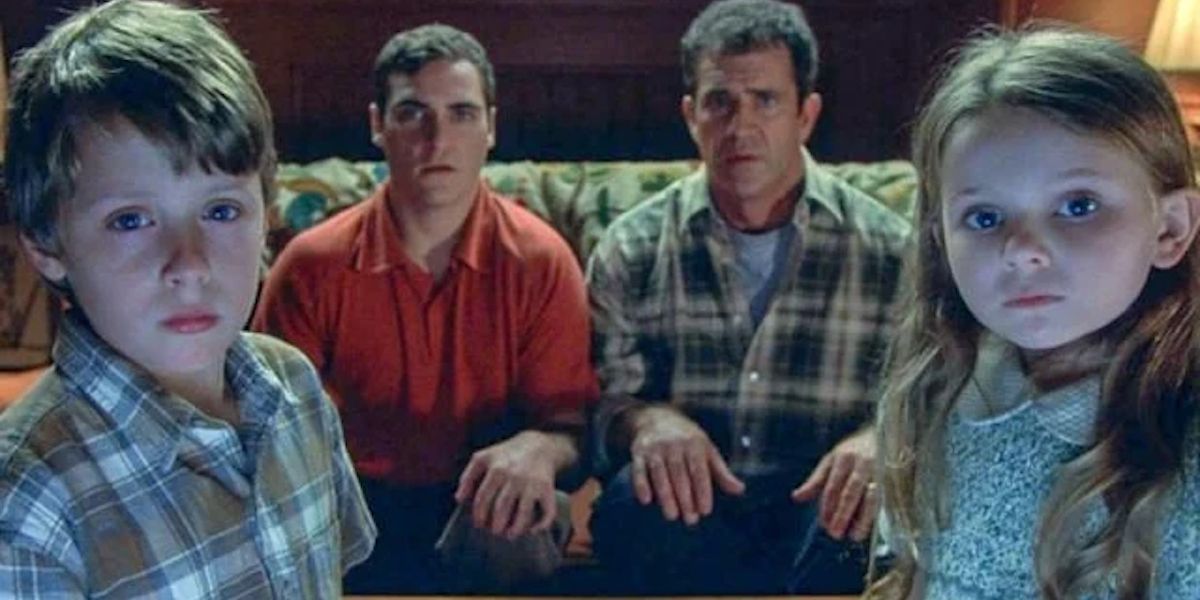

3. Signs

And now, what might be Shyamalan's lightest film. Signs is another of his works containing a twist that gets derided by critics. I cannot deny that, logically, these critics are correct. But when it comes to appreciating a film, who in the hell cares about "being correct?" Isn't it better, more fruitful, more rewarding to give in to the mysteries of the universe? At the very least, more fun?

Signs concerns an alien invasion, crop circles in cornfields, and the crisis of faith of a preacher, played with committed solemnity by Mel Gibson. It also concerns the new version of their nuclear family — the overswinging baseball player brother Joaquin Phoenix and the troubled but bright children Rory Culkin and Abigail Breslin — bonded by the looming trauma of the death of the wife and mother, played in a heartbreaking flashback by Patricia Kalember. This family unit, a unit which Gibson tenuously swings in and out of commitment with, is pushed to and past its limit, with Shyamalan finding some of the cleanest fusion of "terrifying set pieces" and "explorations of emotion" of his career. The climactic moments of the film find moments of psychological, humanity-driven anxiety among the visceral, alien-driven jump scares — and most importantly, find character-driven humor and intrigue among it all. Signs is routinely funny, constantly undercutting what we may expect from an alien-invasion horror-thriller with a keenly sniped character read (shout out to Michael Showalter) or a loose, human reaction to abject terror (shout out to Phoenix yelling at the TV).

Above all, despite some critics' convictions, Signs is a very smart picture. It sets up its own logic and plays within it beautifully. There's not a single throwaway moment, nothing planted that doesn't get paid off; it might be Shyamalan's most elegant screenplay. Most beautifully, it's heart-smart, rather than brain-smart. It knows how to make someone feel, and does so admirably, efficiently, and earnestly.

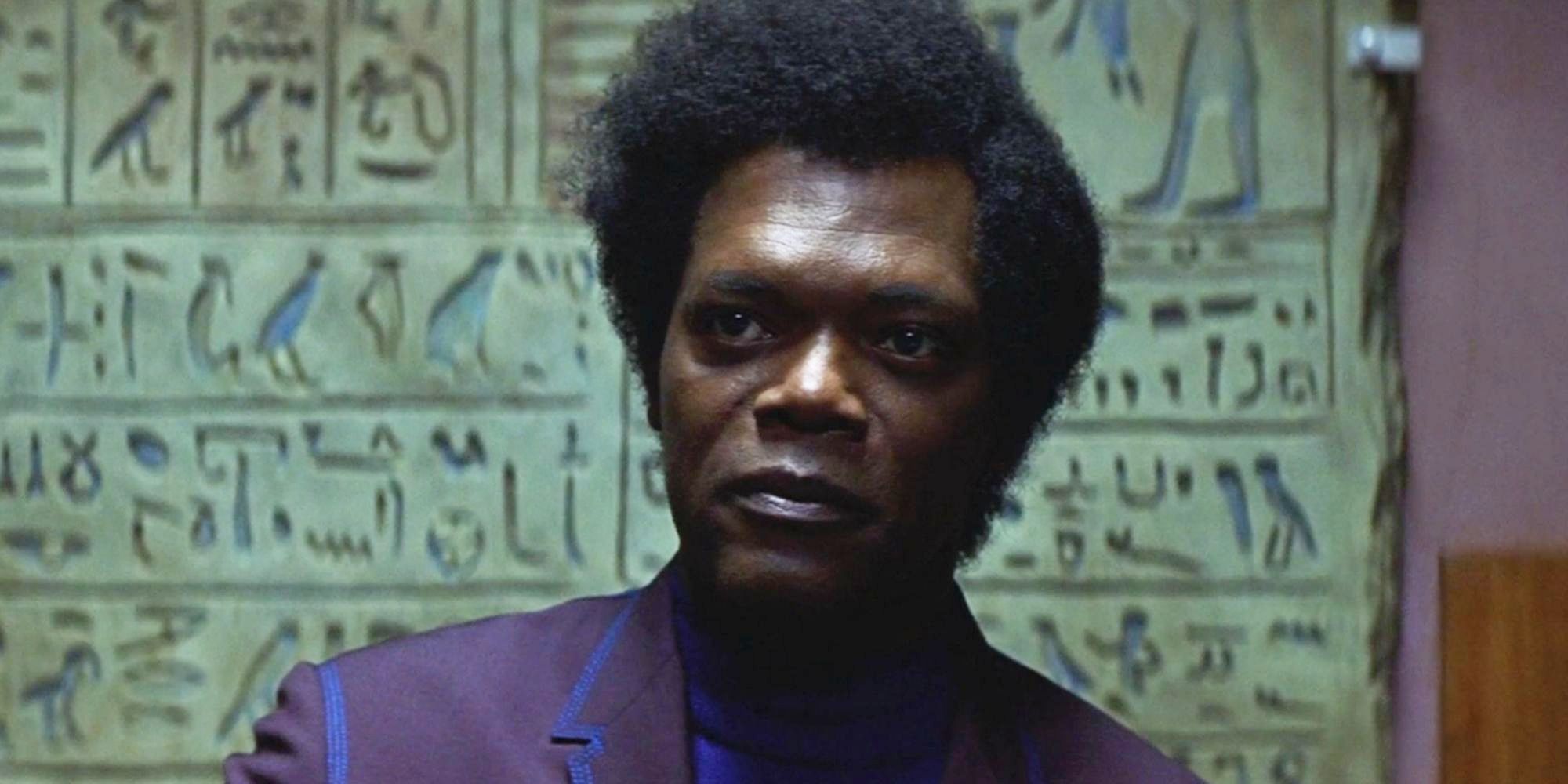

2. Unbreakable

Unbreakable contains the scene, and subsequently the shot, of Shyamalan's career. Staged with DP Eduardo Serra as a fearful, voyeuristic oner, it finds young Joseph Dunn (Spencer Treat Clark) so convinced that his father, David (Bruce Willis), is an unbreakable superhero with super strength, that he points a loaded gun at him at the dinner table. The suspense is immediately palpable, the themes apparent without being ostentatious, and the tension is just about unbearable. How does David get his son to put down the gun? By poking at the biggest unspoken trauma of all: He tells his son, in no uncertain terms, that if he doesn't put down the gun, he will leave him, leave his mother (Robin Wright), and never love them again. Harrowingly, Joseph puts down the gun. A brief sigh of relief, despite everyone's worst fears just being spoken aloud. But it's a lie... right?

Unbreakable is a superhero origin story in slow motion. In a mediascape saturated with "superhero deconstructions" like Logan, Deadpool, and Watchmen, Unbreakable still feels like the most genuinely deconstructive, heartbreaking, and provocative statement about the genre to date. David, in his unbreakable bones, does not want this freaky gift. The film follows suit, eschewing a bright and poppy "superhero film" aesthetic for oppressively dark blues, shadows, rainstorms, and intentionally crafted sequences emphasizing pain and growth over ease and spectacle. Unbreakable was released in 2000, the same year as the breakthrough superhero film X-Men; even that film's flirtation with literal darkness and emotional complexity don't hold a candle to Shyamalan's work. Because, again, X-Men ultimately wants to be a superhero movie; Unbreakable slowly lurches toward its ultimate destiny with nothing but pain, apprehension, disclarity, and regret. Samuel L. Jackson's Mr. Glass, who like David's son wants desperately for this to be a traditional "superhero story," is soonly thereafter revealed to be the film's supervillain, a man so arrested by the traditional conventions of this modern pulp/myth method of storytelling that he's killed countless to make it happen. In all of this struggle, internally and externally, Unbreakable yields such unorthodox riches.

I go back to that kitchen table oner because of its willingness to play every side of a thematic and genre-embedded argument. It speaks to a kind of future-tense grief, domestic disturbances, and the bending of a high concept until it breaks. It achieves terror, heartbreak, and a kind of love through raw emotions, rendered with the utmost control. It's "the truth," told through "a lie."

1. The Sixth Sense

I wish I had some kind of twist ending to this list. But you just can't deny how powerful, beautiful, aching, scary, and rich The Sixth Sense remains. The film that put Shyamalan on the map, added dozens of scenes and images to our pop-cultural lexicon, and influenced a strain of prestige horror we still see in contemporary works like The Babadook, The Sixth Sense is a masterwork, plain and simple.

Cole (Haley Joel Osment) sees dead people. Malcolm (Bruce Willis) is his psychologist. The two figure out why Cole is seeing spirits, what Cole and these spirits need to do to find peace, and what Malcolm needs to do to reconcile with his oddly distant wife Anna (Olivia Williams). Just about every single character in this film, including Cole's mother Toni Collette and poor ghost girl Mischa Barton, is gifted with a beginning-to-end arc, with every piece of tearful catharsis an organic conclusion to the pieces that came before. At its best, which is often, The Sixth Sense ironically explains the fate of Malcolm before he, and we, realize it, through the rules of these ghosts and their need for closure, threading together Shyamalan's love of clever screenwriting with sentimental character exploration. The scares of the film are near-perfect pieces of craft and simple ingenuity, ranging from visceral (the kitchen cabinets suddenly opening) to psychological (Barton's realization she's a victim of Munchausen by proxy) to combinations of the two. It's prestigious without sacrificing terror; it's scary without sacrificing good taste; it's just about a damn perfect film.