The reason that Martin Scorsese has remained the most important and unpredictable American filmmaker currently working is that he makes movies that feature varied, wise questioning of major subjects like faith and violence while also conveying why those subjects are so popular. In Shutter Island, it’s clear that Leonardo DiCaprio’s nerve-wracked detective has lost connection to reality to erase painful memories, and Scorsese both shows the lengths of his madness and the unrelenting terror that those remembrances bring to him. His movies are entertaining without compromising the intellectual backbone of the narrative, which puts him in the same league as artists like David Fincher, P.T. Anderson, Clint Eastwood, Richard Linklater, Wes Anderson, and Steven Soderbergh.

As fans of his films already know, Scorsese is a fan of classic rock, crooners, and soul music, and his usage of certain songs have become iconic at this point. When The Clash’s immortal “Janie Jones” comes on in Bringing Out the Dead, the immediate cutting and rush of the imagery of New York City streets seems to embody Joe Strummer’s reckless anger and skepticism better than any music video ever did. The same thing with his use of “Gimme Shelter” or Johnny Thunders’ “You Can’t Put Your Arms Around a Memory.” Scorsese’s best films have the same feeling as these timeless tunes in both their complex political concepts and societal urgency as well as their essential, unyielding entertainment value that can be felt by any viewer.

For those getting ready to start with Scorsese’s filmography, I suggested to start with GoodFellas, The Departed, and Raging Bull, arguably his three most universally admired films. 2006’s The Departed brought him his first Oscar, while nearly every crime film since GoodFellas has more-or-less cribbed ideas wholesale from the masterpiece. After those, to get deeper into his style and variety of tone and texture, I’d go with Taxi Driver, one of the very best films of the 1970s; The Wolf of Wall Street, his wild take on Wall Street culture through the lens of notorious trader Jordan Belfort; and The Last Waltz, the filmmaker’s most well-regarded documentary that chronicles The Band’s last rollicking concert. Finally, following these six major titles, I’d get into less celebrated fair like Bringing Out the Dead and Shutter Island, two great movies that got less love from critics and audiences alike. By the time you get to those titles, however, I can only imagine you’ll rightly want to see everything the man’s ever helmed.

To Start: 'Goodfellas'

Crime tends to begin as an act of liberation. When Ray Liotta promps the opening credits of GoodFellas with “All my life, I wanted to be a gangster,” he’s referring to a childhood in a cramped, strict home where beatings often enforced a rigid moral code. As GoodFellas demonstrates clearly, moral codes are mere window-dressing for organized crime figures. Liotta’s Irish gangster believes in the brotherhood of organized crime under Pauly (Paul Sorvino), and Scorsese is generous in his depictions of the power and illicit rewards of his place in the family. When a large chunk of money is on the line, however, Robert DeNiro’s scheming Jimmy begins to off fellow capos and criminal colleagues, under the name of protecting their business and in fear of an inevitable rat. Scorsese concludes that a life in crime requires betrayal and a distinct kind of personal weakness, but the thrill of the work – the violence, the sex, the drugs, the privilege, etc. – is never lost on him.

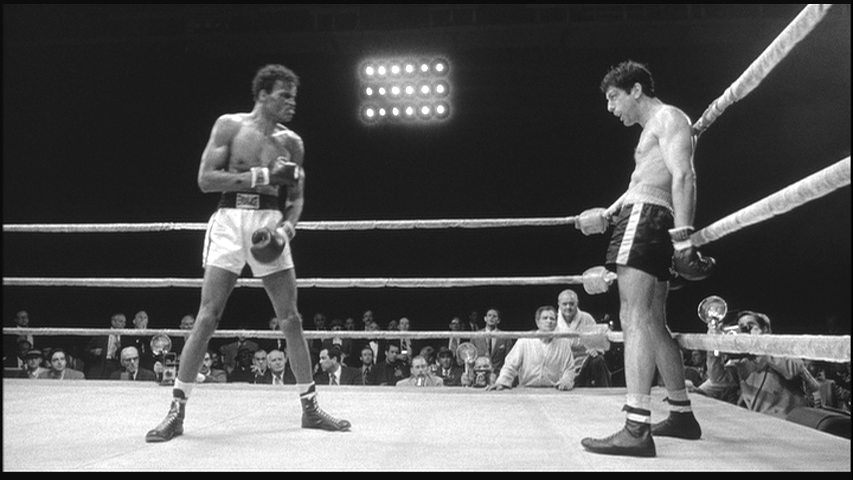

'Raging Bull'

A central tenant of Christianity is the punishment of the body in the name of the lord as a way to expel sin, and that’s where Scorsese hits hard when tackling the tragic life of New York boxer Jake LaMotta. As played by a imposingly physical and bracingly aggressive Robert DeNiro, LaMotta is a beast wrestling with the grace of performance and deeply personal romantic and social insecurities. Like Scorsese himself through his films, the pugilist seeks the sublime through violence, either visited upon his opponents or allowed against his own body. At home, he doesn’t trust his come-hither bride (Cathy Moriarty) and is having trouble in the bedroom, which is another driving force for his thoughtless brutality. The director gives the boxing arena a feeling of striking grace in the opening moments, and later, depicts it as a realm of ecstatic, skilled combat. When things get dark, with LaMotta left an overweight, crass husk of his former self in his older years, the filmmaker and DeNiro infuse the character with a haunting sense of regret, a knowledge of the bad things inside you that you can’t always defeat. Here, Scorsese confronts the very real possibility of becoming washed-up due to personal demons, and in the process, crafts one of the all-time great acts of artistic self-excoriation.

'The Departed'

In adapting the Chinese action hit Infernal Affairs to modern-day Boston, Scorsese once again returned to the dubious devotion of the criminal code of loyalty. The Departed is a far funnier, more audacious film than its source material, both of which tell the story of a cop who infiltrates a gang at a same time as the gang gets a man on the inside of the local police department. Jack Nicholson’s demonic gang leader Costello is portrayed as the incarnation of indulgence, who snorts coke and drinks constantly to cope with incessant paranoia and a veracious bloodlust. Scorsese sets Matt Damon’s criminal in cop’s clothing and Leonardo DiCaprio’s undercover man against one another, connected by Costello and Martin Sheen’s manipulative, seemingly principled police captain. To be effective as a criminal or a crime fighter requires a disintegration of identity in Scorsese’s eyes and faith in these jobs is also dependent on a certain level of gullibility. The faultiness of both endeavors, and the personal weaknesses that drive these men, is shown, while Scorsese’s executes some of his most rousing action scenes and extended bits of dark comedy, but the director is also clear when he conveys that little good is done on such a large stage otherwise.

Advanced: 'The Wolf of Wall Street'

Right when 2014 was closing out, in walked this malevolent masterpiece and made every other film that came out that year feel dated, timid, and deeply compromised in comparison. In the wake of the financial crisis, Scorsese made a film about Jordan Belfort, the famed stock-market playboy who helped give Wall Street a name synonymous with obscene wealth and endless indulgence. Leonardo DiCaprio brought out his inner spoiled, doped-up brat for the role of Belfour, and his dramatic intensity is matched by an all-but-untapped-before sense of comic timing and physicality. To match DiCaprio’s lascivious billionaire-hellion, Scorsese delights in low, basic thrills – road head on the way to the office, snorting cocaine out of a prostitute’s backside, and spending someone’s mortgage on out-of-circulation downers. To deny the allure of capitalism or the power of money would make Wolf of Wall Street toothless, and as Belfour’s life goes international and he becomes abusive to his wife (Margot Robbie) and daughter, more than a few marks are left. The movie openly parallels the structure of GoodFellas, as if to suggest how the nature and look of crime has changed over the decades, brazenly suggesting that the lack of bank regulation in the Reagen era essentially made organized crime a normalized growth industry.

'Taxi Driver'

Seeing Taxi Driver for the first time is an atomic-bomb moment for most young cinephiles, a blunt awakening to the psychological depths and dark realms of desire that cinema can invoke when called upon. The story of Travis Bickle, an alienated NYC yellow-cab driver played with potent ferocity by Robert DeNiro, is the story of a man who wants to make a statement, a disturbed individual who thinks he’s going to change the world. Scorsese infuses Paul Schrader’s script with a political and personal anxiousness, and a profound understanding of the transfixing power of violence as a kind of forced forgiveness. Schrader’s screenplay casts Bickle, who becomes obsessed with the people and the message of a local polticical campaign, as a self-sure savior, out to clean up the streets like a biblical hero. As Scorsese depicts his journey, however, this certain belief in himself as a hero does not change him from looking like a complete psychopath. Decades later, Bickle’s attack on moral passivity remains one of the most disturbing fictions to come out of the hot, horrid New York City of the 1970s.

'The Last Waltz'

In considering Scorsese’s legacy, one cannot avoid his astounding work in the realm of documentaries. Music and musicians have often been his primary focus, from the enveloping No Direction Home to the spiritual George Harrison: Living in the Material World to this rollicking concert film. Scorsese’s cameras give us a full view of the star-studded final concert from The Band, including a coke-nosed Neil Young trying to grope Joni Mitchell and a uniquely soulful Van Morrison. In between songs, the filmmaker interviews the wildly inebriated band mates about the joys and drawbacks of touring, the ease of getting drugs and good drinks, women, and other intimate details of life as a pop rock group. What emerges is a wildly distinct vision of the occasionally unsettling details of living on the edge, far away from home, and the tremendous works of music that come raging from those experiences, both in basic performance and in skilled musicianship.

Further Research: 'Shutter Island'

Easily the most undervalued masterpiece in Scorsese’s arsenal, this untamable, fire-breathing horror tale brings out some of the most palpably original images in the filmmaker’s entire oeuvre. Guilt goes horrific here, and the titular island becomes a vibrant, unnerving psychological landscape for Leonardo DiCaprio and Mark Ruffalo’s detectives on the lookout for an escaped patient. Memories too terrible to speak of rise in a plumage of flames then turn to ash, while murderers become confidants and guards come off like demented, power-hungry savages. The constant feeling of disquiet and confusion is purposeful, and potently evokes how grief and guilt can push us to fashion ourselves a psychological escape, no matter how dangerous that escape may end up being to our well being overall. Here, Scorsese tips his hat to Jacques Tourneur and Val Lewis but he creates an original horror masterpiece that speaks to his own violent, unshakeable fears as a husband, father, artist, and sinner.

'Bringing Out the Dead'

Bringing Out the Dead: Nicolas Cage gives one of his most compellingly mad performances to date in Scorsese’s blazing story of a burnt-out EMT working pre-millennium NYC on the graveyard shift. Scorsese depicts the work of EMTs as that of saints or angels, skilled technicians who offer physical salvation from death when they can. When we meet Cage’s sleep-deprived Frank, he hasn’t saved anyone in a long time and the strain of his failure can be felt in his jittery demeanor and desperate, anxious way of speaking. The movie sees him being shuffled between other stressed men of the panels for partners, from Ving Rhames’ faux-preacher to Tom Sizemore’s angry malcontent, but the central moral conundrum comes from the nature of salvation.

Can one honestly say that salvation is always synonymous with living? What if killing someone to avoid undue pain was a holy act? These questions seem to be pressed against the inside of Frank’s brain, and his attempt to balance them while sparking a hesitant romance with Mary (Patricia Arquette), the daughter of a comatose stroke victim, lead down a strange corridor of life in the five boroughs. After two of Scorsese’s least profound features – Casino and Kundun – Bringing Out the Dead felt like both a reviving of the antic artist that made Taxi Driver and the birth of a wiser, more audacious visionary.