Bleary sunsets, neon lights against wet streets, electric guitars and synths and electronic tom toms just wailing, professionals just being capital p Professionals, Al Pacino screaming "'Cause she's got a grrrRRREAT ASS!" Clearly, Michael Mann is one of our premiere film stylists, an auteur whose sensibilities and proclivities are defined and refined as early as his debut picture. In fact, the Chicago-born Mann, a tough-talker notorious for running tough sets built on authenticity over everything else, sometimes gets dinged for a "style over substance" approach, especially in his iconic TV work like Miami Vice. But underneath the hood -- and especially underneath the hardened shields of his characters -- there's a ton going on in the engine.

Grab a pair of shades, get yourself some repressed trauma, and find either a pristine 35mm film camera or a prosumer digital video camera with a ton of noise: We're ranking the best Michael Mann films, from his worst to his best.

11. Public Enemies

Yikes! Jeepers! And fully, woof! Public Enemies is likely Mann's only out-and-out dog, a morose, cold, visually ugly piece of filmmaking that seems perversely uninterested in any traditional facets of a period gangster drama, to its own severe detriment. The film tells the true story of John Dillinger (Johnny Depp), a notorious bank robber who captured the hearts and imaginations of the public in 1930s Chicago -- especially jazz singer Billie Frechette (Marion Cotillard). Hot on Dillinger's heels? The buttoned-up FBI agent Melvin Purvis (Christian Bale), acting under orders by an increasingly single-minded J. Edgar Hoover (Billy Crudup). All of this, on paper, sounds like a slam dunk for Mann. In practice? More like a half-court three that accidentally hits the mascot.

The film, released in 2009, represents the absolute creative nadir of Mann's 2000s obsessions and experiments with digital cinematography. But unlike other digital photography pioneers of this era (your James Camerons, your Robert Rodriguezes), Mann wasn't interested in replicating the look of film. Instead, Mann used gnarly, grimy, grainy HD photography with digital cameras that couldn't care less about looking like any standard Hollywood picture. Some of Mann's experiments with this style of filmmaking work like gangbusters (we'll get to those later). But Public Enemies, the first film Mann made entirely digitally, does not, hard. Mann's images, rendered by his usual DP Dante Spinotti, are flattened, desaturated, cheap-looking, bleary, and during the action sequences, literally painful to watch. The era Mann is covering was full of passion, jazz, and the tantalizingly ambiguous deification of flamboyant criminals. Mann's visual swath of "boring, ugly cinematography," combined with the performers' muted work, combined with its aggravating reliance on realistic procedure over human drama, sidesteps all of that intrigue in favor of something much more dubious. All of these facets and more are used by Mann regularly to much better effects. Public Enemies is a fling off the dartboard and thensome.

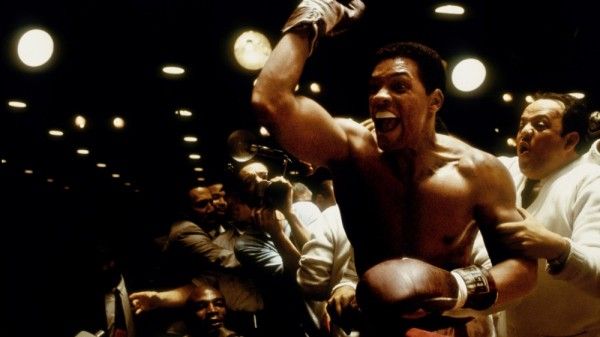

10. Ali

Do you want to know more about Muhammad Ali, the world-famous boxer and social activist? I think I would recommend that you not watch Ali as a starting point.

In some ways, Michael Mann’s Ali, starring an Oscar-nominated Will Smith in the title role, plays like the famous documentary on the man When We Were Kings (a film you should watch if you want to know more about Ali), but, like, if When We Were Kings were stretched out into a moody, ambient-leaning slow motion. The opening 25ish minutes of Ali, in particular, borrow some of the wild, fast-paced usage of montage and music from When We Were Kings — just with a lot less clarity, purpose, and immediate context. Mann stages a prolonged musical performance from Sam Cooke (David Elliott) and cuts between lots of disparate, in media res moments from Ali’s life (again, starting the picture rapidly in media res is a trick Mann does in other films to much better effect). But if When We Were Kings cuts images to the bone, Ali cuts images and leaves a ton of meat, gristle, and fat — and then refuses to tell you what kind of meat it is.

The word “reach” came to mind a lot while watching this film, especially in Smith’s performance. He is, no joke, one of my all-time favorite movie actors, and the idea of him teaming up with Mann to depict Ali (who publicly endorsed Smith) excited me to no end. But his take on the icon both reaches counterintuitively toward a sketch-like impression while also feeling strangely held back. Smith seems to be deciding to show no emotion in his face when playing Ali — the moments of performance that do pop (like a lovely winter-set scene late in the picture) pop because Smith allows himself to actually emote and tap into what makes him naturally effective as a performer. And when Smith is forced abruptly into more traditionally written and staged “biopic scenes” (Ali and his dad fight! Ali says quotes we all know and love! Ali triumphs in the Rumble in the Jungle!), it feels less like a breath of fresh air and more like another bafflingly obtuse decision from Mr. Mann. Mann has applied his aesthetics to more traditional, prestige genres before and come up quite successful. Ali is, mostly, the filmmaker rope-a-doping himself.

9. Blackhat

Despite Blackhat‘s reputation as a critical and financial failure, there’s a ton about the sublimely absurd, globe-trotting hacker-action-thriller that I can get down with. Mann’s eye for texture, after the mishap of Public Enemies, comes back in full force, his digital photography a perfect fit for the film's incomprehensible-on-purpose digital plot. The action sequences are spartan and effective, the dialogue is full of brain-cracking witticisms that I love from Mann, and Viola Davis acquits herself to this world perfectly. But unfortunately, Chris Hemsworth, as computer hacker extraordinaire Nicholas Hathaway, can’t quite wear Mann’s style as a suit that fits well. I think Hemsworth works best when he’s allowed to show vulnerability, either in emotional desperation or in humor, and Blackhat demands none of it. Instead, it mostly wants him to be an icy wall of coolness, a straight-up badass hardened gangster who can shoot off rat-a-tat lines like “I did the crime, I’m doing the time, the time isn’t doing me” and be believed. But I, mostly, do not believe Hemsworth in these moments. It all feels like a costume, from his not-so-great Chicago accent (just let him be Australian!) to his choice that “badass equals monotone.” And, for the record, Hemsworth tends to agree with me, telling Variety, “I didn’t enjoy what I did in the film. It just felt flat, and it was also an attempt to do what I thought people might have wanted to see. But I don’t think I’m good in that space.”

Beyond Hemsworth's central work? Blackhat deserves a reappraisal. Mann's sequence work shocks from the very beginning (even if some of the digital transitions and explorations through computer chips feel a little cribbed from David Fincher), his love of professionals spouting jargon continues to be exciting even when (especially when!) it's nonsensical, and once again, Viola Davis, Viola Davis, Viola Davis. If you can get past the film's unfortunate reputation, you'll find a muscly, unique, digitally prescient action-thriller to sink your flash drive into.

8. The Last of the Mohicans

Everything about this film is handsome. Its astonishing usage of color temperature and shadow (Spinotti just out here flexing), its widescreen vistas of beautiful nature corrupted by brutal battles, its utterly sweeping romance at the heart of its story, its beautifully melancholic score from Trevor Jones and Randy Edelman, and obviously, Daniel Day-Lewis shirtless with long hair. This is all to say that The Last of the Mohicans feels perhaps the least like a "Mann film," and the most like a prestige picture from a talented filmmaker in command of his craft, eager to play to the people he needs to play to for mass consumption and Oscar buzz. None of this is a knock against the film -- it's sort of to Mann what Arrival is to Denis Villeneuve, an eminently watchable, emotion-forward, and even optimistic film that doesn't unnecessarily placate, patronize, or pivot away from its auteur's best impulses.

There are still Mann-isms, don't you worry. Day-Lewis' delivery of "Someday I think you and I are gonna have a serious disagreement" is a piece of aggressive, contemporary feeling dialogue that would fight right in to his modern-day crime epics. Mann still loves casting his heroes, caught between the obligations of professionalism and the tempting cascade of love, underneath righteous glows of sunset. And his action scenes still startle with their frankness -- especially an "attack the line" sequence played eerily with no music. But underneath it all, more so than his other films, is a genuine Hollywood love story between Day-Lewis' Hawkeye and Madeleine Stowe's Cora. And wouldn't you know it? When Mann treats love as less of a brief, unobtainable object in the way of man's need to fulfil his lot in life, and as more of "a nice thing that happens," it results in really nice, genuinely romantic work. Many of Mann's films feature sensual love scenes as mini-breaks for their hardened characters' true paths -- in this one, love is the path.

The film's inherent narrative, however, does ring as problematic upon modern eyes. Telling the story of the French-Indian war, Day-Lewis' Hawkeye is a white man adopted by a Mohican tribe, tasked with assisting the British army of colonizers against the French army of colonizers, who are being assisted by the Huron tribe, represented most fiercely by Magua (Wes Studi). Mann's fidelity for history and accuracy of this already tricky plot grinds up against his need to make a movie-star-centered, accessibly prestigious motion picture, resulting in lots of ickiness vis-a-vis making certain colonizers heroes, colorism between heroic, lighter-skinned Natives and villainous, darker-skinned Natives (the scene in which Day-Lewis whitesplains Studi's insistence on helping "the white man" is really something), and borderline fetishization of certain violent practices (scalping, ripping hearts out of chests, etc.). Plus, the aforementioned score, while beautiful, takes its cues not from Native folk songs, but from Scottish and other European melodies. Why is this movie so eager to frame white, European-descended people as its heroes? Well, I think we likely know the reason why.

At the time of its release, 1992, I'm sure this film felt in some ways like a breath of fresh air regarding Native representation. Now, I'd like to see it rebooted with its supporting, actually Native filmmakers and cast members taking center stage and owning their own story.

7. Manhunter

Now we're talking. When people picture Michael Mann's cinematic aesthetics, I imagine Manhunter will be the first film at the tip of the tongue for many. Based on Thomas Harris' Red Dragon, and coming out well before Jonathan Demme's The Silence of the Lambs cemented that particular version of the Hannibal Lecter mythology (to the point where Mann changed his name to "Lecktor"), Manhunter follows a classically painstaking-but-tortured male Mann protagonist named Will Graham (William Petersen). He's a gifted FBI criminal profiler, able to empathize to a dangerous degree with the sick and sadistic killers he's tasked with hunting (rendered in the film by Petersen yelling at VHS footage of the victims, which is both fascinatingly simple and genuinely upsetting). Jack Crawford (Dennis Farina, a truly pure Mann actor) must get Graham back from his cozy, beachside retirement with his family and fling him back into the furnace, as a new killer is on the loose: The Red Dragon, played with exacting eeriness by Tom Noonan. Can Graham tame this beast among humans once more? And perhaps more importantly: Should he?

As for the Hannibal of it all, Brian Cox plays the cannibalistic, Frasier Crane-esque serial killer with a chilly formality. Unlike Anthony Hopkins' portrayal which luxuriates in the fun of his intellectual games, or Mads Mikkelsen's NBC portrayal which tempts his prey by stately, deadpan splendor, Cox gives his Lecktor a weaponized shield. He's smart as hell, yes, and eager to toy with Will even while behind bars, yes -- but it isn't out of a sense of fun. Like the best of Mann's characters, this Lecktor does this shit simply because he has to, because he's a damn professional. Watching him hastily agree to look at Will's case files just because he's annoyed that Will can't do it himself is a primely dry piece of mordant comedy speaking to this character need -- and then Lecktor mostly disappears from the picture, keeping the hunt squarely between Will and the Red Dragon.

While some of Mann and Spinotti's coverage feels a little too square for my taste (some of the "shot-reverse-shot" depiction of dialogue is going for journalistic objectivity but lands on "cheap television go-go-go" instead), much of their visual grammar is off the freaking leash. Skies impose on everyone, whether they're brightly blue in the daytime, eerily white in the moonlight time, or blasting orange and red during the sunlight. When the film starts cascading into pure horror sequences (i.e. anytime the Red Dragon does anything), Mann's command of the relationship between sound and image shines with frightening sheen. It's a beyond earnest movie, making some of the stranger and even sillier choices (i.e. anytime the Red Dragon's crimes are scored by moody pop music with lyrics) feel less like bugs and more like features (and the final shootout, set to "In Da Gadda Vida," makes up for it and more). And while some of the character work reads a little thin or archetypical (truly, what on earth does Joan Allen's blind character gain from spending time with the Red Dragon?), it also features character choices that might be the purest manifestation of Mann's purview, particularly when Will Graham offers himself as bait to the Red Dragon. After all: What else can a professional give but himself fully, in heart, soul, and body?

6. The Keep

And now for something completely different. If you've ever wondered what it might be like if Michael Mann decided to be John Carpenter, watch The Keep and prepare to have your friggin' face blown up. The production and eventual "final cut" of The Keep is notoriously troubled, from stories of Mann not sure what he wanted his monster to look like even when it was time to film it, to their visual effects supervisor Wally Veevers dying before climactic visual effects were completed, to an initial 210-minute cut (!) that the studio chopped down to 96 minutes (!!) against Mann's wishes, eschewing things like "plot comprehension" or even "basic editing continuity" in the process. But you know what? The final product, however maligned and maladied it is, absolutely rips. Getting absorbed into this film's wild choices and rich atmosphere felt like diving into an iconic prog-metal album. Do I know what the story means? I'm not sure I care when the music sounds this assuredly bold.

The horror-fantasy-WWII hybrid concerns a group of Nazi soldiers (including Gabriel Byrne) attempting to find treasure in a Romanian mountain's keep. They technically do so -- but unleash a vicious, vindictive monster hellbent on consuming human lives (voiced with startling menace by Michael Carter). To try and take control of this monster, the Nazis must turn to a Jewish historian (Ian McKellen) who may have the keys to understanding the symbols and motives behind the monster. But as it turns out, the monster wants to offer McKellen eternal youth -- in exchange for his soul and bidding, of course. Oh, and also, there's a fearsome, mysterious warrior named Glaeken Trismegestus (Scott Glenn, cool as hell) who shows up when the monster is unleashed to try and stop it himself.

That is about as best I can do regarding a "plot summary." But man, does "the plot" not matter when it comes to enjoying The Keep. It is an absolute triumph of atmosphere, of style, of confident experimentation. Yes, there are strange lapses in narrative and action due to its chopped up editing, but this all adds up to its puzzlingly pleasurable effect. Mann's imagery is striking, surreal, and color-corrected masterfully -- a perfect encapsulation of all of the genres he's playing with, not to mention his typical style. The Tangerine Dream score is wall-to-wall syrupy bangers, providing an anachronistic bed of synth-driven liquids to the period-set action. Mann, frankly, should make more straight up genre pieces, because when he turns the screws vis-a-vis supernatural horrors, triumphs, and literal monsters, wow is it effective, and wow does it provide narrative catharsis we rarely get with one of Mann's films. If you're fond of retro-styled genre films like Mandy, or want to see what a Soundcloud codeine trap remix of Raiders of the Lost Ark might look like, The Keep is your new cult favorite.

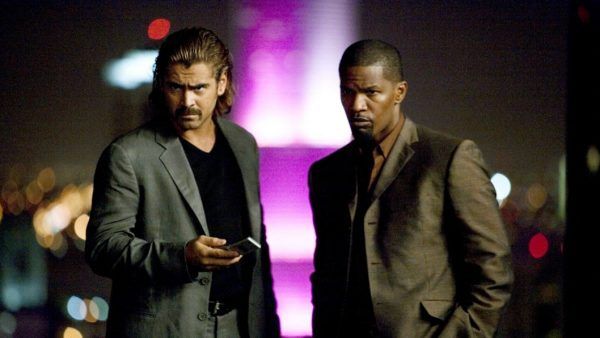

5. Miami Vice

Miami Vice, Mann's 2006 cinematic re-entry into the television world he originally created in the '80s, likely has the most exciting opening sequence of his entire career. It starts with the most "in media res" shot anyone has ever "in media res'd" -- a contextless, floating, handheld shot of a bunch of people partying in a loud nightclub. Suddenly, our Miami police officer leads, Colin Farrell and Jamie Foxx as Crockett and Tubbs, rocket through the scene, already in the middle of a damn case. What's the case? Who knows -- Mann has mixed the audio so loud that we can barely hear their audio. We're just thrown headfirst into their world of confusion, of roaring chaos, of every single line between good and bad blurred. Miami Vice is perhaps the most subjective film Mann has ever made, throwing us directly into the psychological point of view of its troubled characters, resulting in a work of startling purity.

The plot details involve drug deals, undercover cops, the idea of "going too deep" as a way of life, double-crosses, shoot-outs, betrayals -- all the kind of crime drama goodies you'd expect from a filmmaker whose bread and butter are "epic crime dramas." Mann and new DP Dion Beebe use a lot of that prosumer digital photography they're so fond of to render these crime capers in vividly, strikingly detailed imagery. One sequence, taking place during the middle of a literal hurricane (this set is another hall-of-famer of "insane Mann set practices" involving fake drug busts, real criminals as actors, Foxx demanding a raise and equal billing for his supporting role, and of course, shooting during a literal hurricane), takes advantage of the wide-capturing sensor of the digital cameras, resulting in an image I've never seen on film before or after. The sky is pitch-black -- kind of. It's also alive in purple fluidity, with lightning streaks cascading clearly, frightening their characters and symbolizing the sheer magnitude of their cases, their lives. Miami Vice shifts to level of clarity only on occasion, while primarily sticking around in the ground-level muck of its antihero characters.

Miami Vice also might have the strongest female character in all of Mann's usually male-dominated filmography: Gong Li as Isabella, the drug lord Montoya's (Luis Tosar) business advisor and lover, an absolutely consummate professional who's willing to put her body on the line in a way that reminds me of Manhunter's male protagonist. She finds a kindred spirit in Farrell's Crockett, and the two embark on a hidden, star-crossed love affair that pushes Mann's philosophies to their limits (and is perhaps the second-most romantic Mann love story after Mohicans). I truly and desperately want these two to settle down, stop getting into trouble, and just be with each other. But if you've seen even one Mann film, you know it ain't that easy. And Miami Vice frames that doomed, existential journey in as first-person of style as possible, much to its unique benefit.

4. Thief

Mann's debut film, the 1981 crime thriller/character study Thief, is, to my estimation, one of the great feature debuts in American film history. Not just because it's a great watch -- and it really is -- but because it introduces Mann's artistic impulses, stylistic flourishes, and narrative obsessions with crystallized confidence. Thief is both the template for the rest of his career, a high point of his career to this day, and a refreshingly simple tale on its mind, especially when compared to the more labyrinthine, muddled-on-purpose crime epics made later in Mann's life.

James Caan plays a career criminal named Frank. He's -- and this just might surprise you -- very, very good at his job, with Mann showing off his considerable safecracking skills with a stylishly exacting preliminary sequence of dark, gritty, and gosh-darn beautiful procedural close-ups. And while Frank's ability at his line of work is unquestioned, the violent margins around him are beginning to close in, and the desire to settle down and start a family is ringing louder and louder. This desire is unfortunately offset by some debts Frank owes (or should I say "owes"), leaving Frank in the pressure-filled need to pull of some final scores before he can get what he really needs and wants.

Mann's craft in this irresistible criminal caper world is unimpeachable. The film photography bursts with oily, tactile color (especially if you watch it on that Criterion blu-ray, my god), the Tangerine Dream score is, of course, cooler than cool, and the editing work from Dov Hoenig manages to walk the line between "fast-paced intrigue" and "patient character revelations" without ever feeling too quick or too slow. But I will always remember Thief because of one scene, a scene that Man and Hoenig allow to play much longer than anything before it.

Frank is sitting in a diner with Jessie (Tuesday Weld), a woman he's just begun dating. He's just pulled off a great score. And... he can't take it anymore. The two characters thus tumble into an emotionally desperate conversation about dreams, desires, and an unfeeling world that won't let you feel any of it. It's unexpectedly naked writing from Mann, feeling naturalistic and authentic when his worlds usually feel planned within inches of their lives, and Caan and Weld don't need to work at the scene to give it its required interior oomph. The hardened professionals of Mann's world are mere humans, after all. And Mann knew he wanted to say that from film one. Remarkable.

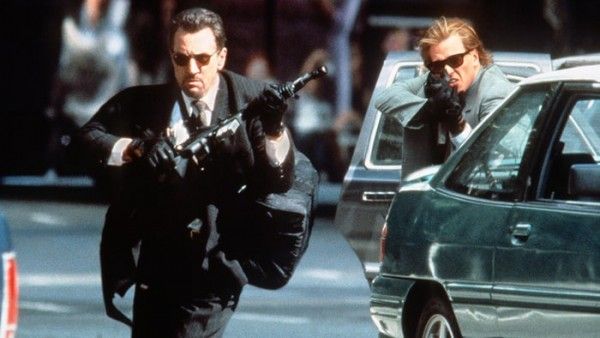

3. Heat

Heat is very silly. But, also, it rips super hard. At a towering "just under three hours," Mann treats his fundamental, simple plot of cops v. robbers and robbers v. cops like a classical, mythic tragedy with A Ton To Say. He absolutely pulls it off. And yet... it's so silly. It's packed to the gills with "masculine prestige film" energy, performances, and craft choices, emitting such a powerful signal it's influenced countless touchstones like The Dark Knight since. It does so with shattering earnestness. Never once does the film question the need to commit this hard and this deep to cops-and-robbers platitudes we all kinda take for granted. Never once do Al Pacino's scene partners, upon hearing their superior commanding officer, eternal archenemy, or wife deliver a piece of dialogue with what I'd call "the weirdest line reading ever," stop and interrogate what just happened. The word "heat" is used around 800 times in varying contexts, and it's all delivered with stoic importance. And I, simply, never wanted it to end.

I could watch Heat for as long as Heat wants to heat up the joint. It is Robert De Niro saying lines like "You wanna be making moves on the street? Have no attachments. Allow nothing to be in your life that you cannot walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you spot the heat around the corner" and believing and selling every damn purple word of it. It is Pacino willing to be a figure of tender empathy, particularly when dealing with his troubled stepdaughter Natalie Portman, or when he hugs the mother of a criminal's latest victim. It is Mann willing to have his characters explicitly state the themes of criminals and law keepers being similar, of professionals not being able to stay present when it comes to personal connections, of the task as the identity. It is Every Notable Male Actor Yelling At Each Other. It is A Long, Loud Shootout In The Middle Of Goddamn Los Angeles In Broad Daylight. It is Did You Know The Diner Scene Is The Only Time De Niro And Pacino Meet?

It is all of these things, made and sold at the highest quality. It is Macho Poetry Bullshit at its finest. Long live Heat.

2. The Insider

If Heat is in some ways a puppy dog let off the leash, The Insider is an older, wisened, and even cynical beast, eager to take its walk more patiently. All the better for it, too, as Mann earns every frame of this two-and-a-half hour exposé. It's the kind of tale for grown-ups that, were it made today, would be given the "six episode prestige limited miniseries" treatment. Thank goodness it came to us in 1999, then, because its muckraking cinematic pleasures deserve to be experienced, appreciated, and luxuriated in in one sitting.

Based on a true story, The Insider follows Dr. Jeffrey Wigand (Russell Crowe), a former executive at a tobacco company who is now interested in blowing the whistle on the tobacco industry's uncaring, unsparing approach to anything resembling "the public health." Lowell Bergman (Al Pacino) is a TV producer for 60 Minutes, CBS' premier newsmagazine program hosted by the figure of journalistic integrity at the time, Mike Wallace (played with incendiary energy and intention by Christopher Plummer). As Bergman decides to take on Wigand's story for 60 Minutes' next big story, the walls close in, hard, from every direction. The tobacco industry threatens Wigand's home and family, skeletons from everyone's closet tumbles into the limelight, even Wallace himself begins to question Bergman's choices. Can the truth -- or something remotely resembling it -- have its day? And will it even matter once it does?

Mann, appropriately, delves into all these questions with journalistic furor. But not necessarily a standard beat reporter. Mann's work here is more like an impassioned editorial writer. He's got all his facts down, sure. But he knows the strongest way to make a point, to change minds, is through emotion. And even when the characters of The Insider struggle with the best way to communicate their own truths and emotions, Mann and his flawless cast (cast Crowe in more low status roles, you cowards!) know how to render them with the perfect mixture of clarity and ambiguity. Somehow, The Insider will make you feel both bitterly jaded and aggressively hopeful about the power of hard work, determination, and telling the damn truth. Like all of Mann's characters, The Insider hopes we never stop.

1. Collateral

I think Collateral makes my number one because of its ideological conclusion that change is possible. So much of Mann's worlds find their characters locked within their professional destinies, with their personal desires taking a backseat. But Collateral dares to dream of a brighter future for Jamie Foxx's leading character. And it all starts with Tom Cruise entering his backseat.

This ain't the charming action hero Tom Cruise, though. This is Cruise's most deliciously evil work to date. He plays Vincent, an older, graying hitman who is nonetheless -- and I'm almost sad this is the last time I'm saying this! -- a consummate professional. He hops into a cab driven by Max Durocher (Foxx), and gives him the kind of task that fans of self-contained mid-budget genre thrillers (like myself) will go gaga for: I have to kill these targets, and you're gonna drive me to all of them. The thrills that occur afterward are, of course, filmed in striking sequences of unbearable suspense and genuine menace, especially given their source is from a handsome (and still charismatic!) Cruise. Mann works with two DPs, Dion Beebe and Paul Cameron, using a ton of, but not exclusively, digital photography to lens their city nights with appropriately hazy, dirty-looking-but-clear depictions of this underworld of crime and corruption. The actions of violence are gut-punching, the tet-a-tet between Foxx and Cruise is engrossing, and praise him, Mann stops everything to a halt to we can go listen to some damn jazz in a damn jazz club. Collateral represents everything I love about Mann's late period aesthetics and narrative points of entry, festooned into a tightly-plotted vehicle of cinematic enjoyment.

But why number one? Foxx, unlike so many Mann protagonists, is not necessarily interested in being the absolute best at his job. He is a wonderful cab driver, to be sure, and takes the work seriously. But he has a dream. Literally and physically, a dream of starting his own business and leaving the cab behind. But emotionally and spiritually, a dream of moving on from what our professions insist we must be. Of evolving. Of finding a new purpose, of finding... love. All of this is established with a charming, lovely interaction between Foxx and a passenger played by Jada Pinkett Smith (who, as you might guess from the picture used, plays heavily into the thriller plot later). And then Cruise comes in and puts this dream to the absolute test, making Foxx "Do His Job" while he "Does His Job," serving almost as the typical protagonist of any other Mann film (it's telling Mann himself isn't credited as a writer).

I don't want to spoil the ending of Collateral for you. But I will say this: You will believe, wholeheartedly, in the ideological messages of change represented by Foxx and Smith. Does this make me a softy for choosing this Hollywood ending as Mann's number one over more hardened texts he's made? Too bad...

...because being sentimental and joyful about the message of films... is my job.