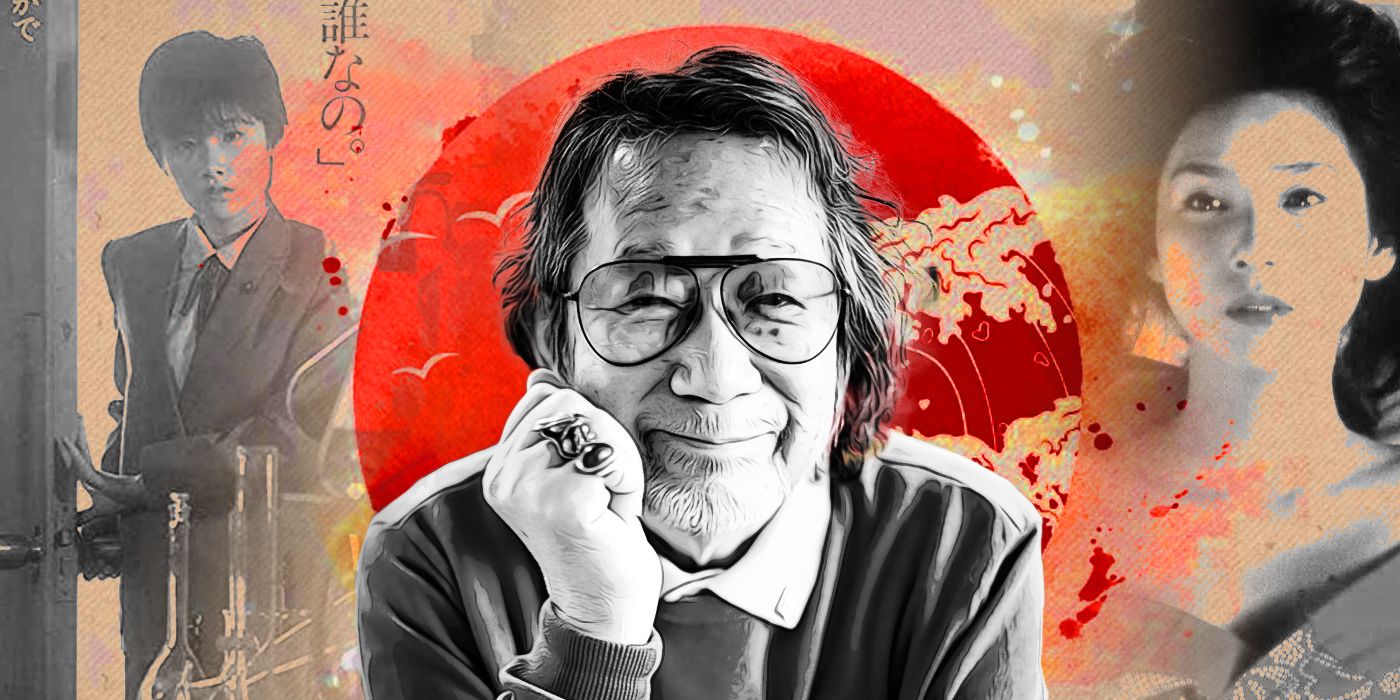

Many film directors are also film buffs, happy to showcase their knowledge of the medium. But even among cinephile filmmakers, there’s nobody like Nobuhiko Obayashi. Where some directors toss movie trivia into their scripts or make films about films, Obayashi spent his entire career showing his love for moviemaking by embracing its artifice. His work is loaded with title cards, irises, stop motion, rear projection, miniatures, matte paintings – you name an old-school movie trick, Obayashi’s used it; often in the most deliberately archaic way possible. Instead of a possessory credit, many of his pictures begin by declaring themselves to be “A Movie.”

Never mistake the man for valuing style over substance, though. Obayashi’s embrace of old-time movie magic puts a whimsical face on his CV, but he explored a diverse range of subjects in a four-decade career. Recurring themes include truths within fantasy, the loss of childhood, and the impact of World War II on Japan. These could be explored to surprising depths, and the contrast between these sometimes dark and ambiguous themes and the joyful artifice of Obayashi’s visual style is fascinating. He was one of the most idiosyncratic voices in cinema from any time or place, but outside his native Japan, he’s always been an obscure figure whose films are rarely seen or even mentioned.

Finding most of his movies is still a tall order, but after today, you’ll at least know what to look for. Here are nine pictures to introduce you to the whimsical world of Nobuhiko Obayashi:

Emotion (1966)

Obayashi first came to prominence as a figure in the experimental film scene of Japan in the 1960s with short films screened on campuses and in event halls. Emotion is the most elaborate of these. It lives up to the “experimental” label: half the credits are in French, half the narration is in English; jump cuts abound, the picture dips in and out of color, and there are multiple peaks behind the camera to look at the group of friends Obayashi made the film with. What scraps of the plot there are concern girls from the sea, sadomasochist parents, and Dracula, but the narrative isn’t even close to the first priority here. Emotion isn’t the most distinctive of Obayashi’s films; the world of experimental filmmaking abounds with shorts of the same aesthetic and thematic preoccupations. But even at this stage in his career, Obayashi’s glee at working with film is evident.

House (1977)

House is, without question, the best-known of Obayashi’s films outside Japan. It’s also weird. “Could be used to wean drug addicts off hallucinogens” weird. The Evil Dead and The Rocky Horror Picture Show have nothing on this cult classic for sheer, unrestrained lunacy. There are girl-eating clocks, death by banana, and a dream logic that collapses in on itself before the story runs its course. But when it’s all so colorful, fun, and underpinned by generational divide and the pain left by war, who cares about a tight plot? Perhaps the most outrageous thing about House is that it was Obayashi’s breakthrough into major studio filmmaking. Having made a name in the art house and as a director of commercials, Toho thought he would be a good choice to give them a movie like Jaws. Not only did he deliver this madcap ghost story instead, but he scored a big hit with it in Japan.

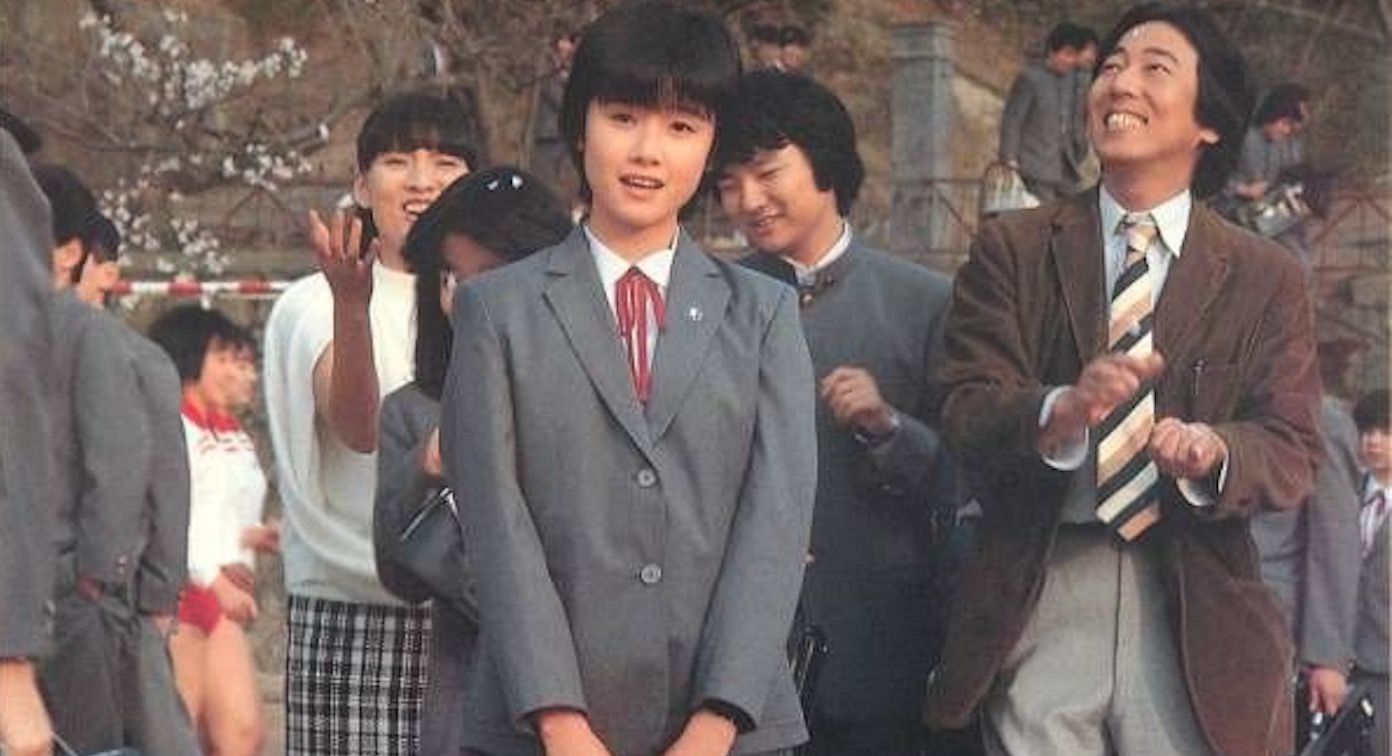

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (1983)

Anime fans might know The Girl Who Leapt Through Time best through the 2006 animated film. In fact, it was originally a serialized 1960s novel, decades before related introspective time loop stories became hit Bill Murray comedies. The 1983 film began as a gift for pop idol Tomoyo Harada from executive producer Kadokawa Haruki. Don’t think that Obayashi was merely a director-for-hire, though – he set the film in his hometown of Onomichi, had the script peppered with anecdotes from his own youth, and he considered it one of his most personal and favorite of his own movies.

The visual flourishes that are Obayashi’s signature are restrained here, not just the old-fashioned effects but the approach to editing. The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is less than two hours but feels longer due to its deliberate pace, which can be difficult to sit through despite an appealing atmosphere of nostalgia. But the pacing didn’t stop the film from becoming a big hit in 1983, nor does it impact the performance Obayashi got out of Harada in the lead role. She shows such an effortless charm in the part that it’s hard to believe it was her first acting gig.

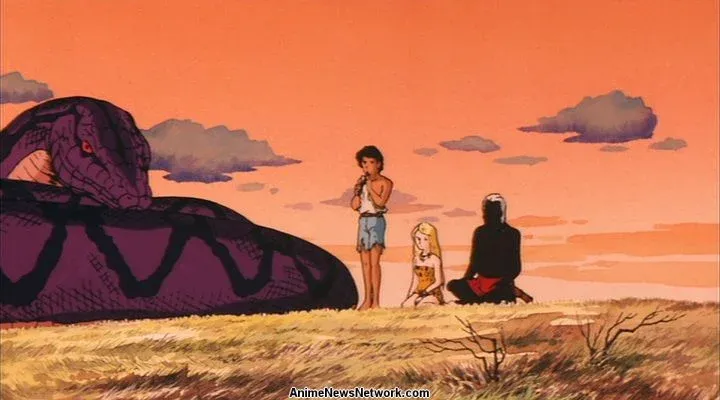

Kenya Boy (1984)

Obayashi frequently used animation in his films, usually pixilation (a stop motion variant done with live actors) broken out for brief moments of silliness. But only once did he direct a fully animated film: 1984’s Kenya Boy. It was another adaptation, this time of a postwar newspaper comic strip, again from executive producer, Haruki Kadokawa. The resulting movie is certainly not silly; just what it is, I’m not sure.

Obayashi and animation director Tetsuo Imazawa had some gorgeous layouts and background paintings to work with, and they weren’t afraid to experiment by alternating between fully rendered shots to pencil test animation. And you can’t deny that a depiction of 1940s Kenya as a land of giant snakes, underground dinosaurs, and Nazi atomic tests is unique. But the lengthy subplot of a savage tribe worshiping a “white goddess” does not sit well, nor does the chest-thumping wartime nationalism. On a technical level, the human characters’ faces are quite stiff. I recommend this as an example of a director’s failure. But even Obayashi’s misses have their moments, and along with those pencil tests and dinosaur sequences, there’s a touching incorporation of the original author, Soji Yamakawa.

Bound for the Fields, The Mountains, and the Seacoast (1986)

Fans of Wes Anderson may see something of Moonrise Kingdom in Bound for the Fields, The Mountains, and the Seacoast. Both are coming-of-age tales with a poetic title directed by an auteur. They both have school-age kids in the throes of young love in the forefront. Both are largely set outdoors, and both take their time exploring childlike whimsy, broad comedy, and emotional fragility in turns.

It's the latter sentiment that comes to dominate Bound for the Fields by the end. Its young love affair is a messier, uncomfortable business compared to Sam and Suzy in Moonrise. And lurking behind all the adolescent flirtation and schoolyard games is the shadow of World War II. The militant nationalism drilled into the young students is uncritically accepted by them at first. Gradually, it mixes with the poverty and inadequacies of the adults in their lives to poison the innocence of their youth. Comedy and tragedy are perhaps most elegantly bound together in Bound for the Fields out of all Obayashi’s films, to beautiful and heartbreaking effect.

Samurai Kids (1993)

Bound for the Fields was a complex and thoughtful look back on childhood; Samurai Kids really is a kids’ movie. The basic plot is a familiar one: a young boy from a dysfunctional family encounters a magical being who changes his life for the better. The magical being in this case is a river spirit in the form of a tiny, broken old samurai, bound for oblivion in the waves of the ocean. Most of the laughs in the film come from his friendship with the family cat and his conflicts with a local crow, but while he’s busy with the animals, there are adolescent insecurities, generational divides, and an ecology message to contend with.

Samurai Kids isn’t going to win any awards for outstanding child acting. Like The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, its careful pacing can be tough, especially around the middle where it seems that the various family and fantasy conflicts will never come together. But it’s worth it to press on into the third act, where everything gels into an exciting, hilarious, and sweet finale. And Godzilla fans should keep an eye out for a posthumous cameo by director Ishiro Honda, a friend of Obayashi’s, as the deceased grandfather.

Sada (1998)

If there’s any point in Obayashi’s career where the tension between his playful visual style and the darkness of his subject matter becomes too much, it’s Sada. The life and crimes of the geisha Sada Abe have been popular subjects for Japanese artists since her sensational trial in 1936, and Obayashi wasn’t the first director to helm a film about her story. His approach is theatrical, even opening with a narrator on an empty stage who runs throughout the film as a commentator and character. This is in addition to Obayashi’s usual bag of old-fashioned tricks.

But Sada’s story – in life, and as portrayed in this film – was marred by episodes of coercion, assault, abandonment, and violence. It isn’t that Obayashi disregards these dark notes; at times, he finds ways to tailor his style to most starkly express them. But other scenes focused on such incidents play as flippant or farcical even within the film’s sympathetic take on Sada herself. That approach, and the subject matter underneath it, make Sada a very uncomfortable watch. Yet it’s a movie that is earnestly trying to say something meaningful about this woman, and one of the most captivating things about movies – or any art –is seeing that effort even when it isn’t slickly produced or easily digested.

Hanagatami (2017)

You might think that Hanagatami was a follow-up to Bound for the Fields; it’s a similar plot with similar themes, told with slightly older characters. But Hanagatami was a long-nursed passion project by Obayashi. Written in the 1970s with his House co-writer Chiho Katsura, based on a novel by Kazuo Dan, he had hoped to make it his first feature film. Instead, he made House, and 40 years passed before cameras rolled on Hanagatami. By that time, Obayashi was diagnosed with stage-four cancer and given just three months to live.

The best, somewhat contradictory way I can describe Hanagatami is that it’s an intimate epic. Its near three-hour runtime and flamboyant visuals give it a grandeur beyond the average drama, and yet it remains tightly focused on a small group of characters and their struggles with the coming war and each other. They’re all connected by complicated feelings toward the dying Mina (Honoka Yahagi) and friendship with the naïve protagonist Toshihiko (Shunsuke Kubozuka), whose memories of youth provide a frame story.

It's not a happy story; even its whimsical indulgences are tinged with melancholy. A title card near the beginning declares that this is “not nostalgia…it’s heartache for all that’s lost.” That sentiment could describe Obayashi’s overall stance on childhood. I don’t know that Hanagatami is the equal of Bound for the Fields in expressing this, but it is a lovingly wrought film with an engrossing cast, and one can well believe a director would spend his entire working life chasing such a project.

Labyrinth of Cinema (2019)

Obayashi defied his prognosis, finished Hanagatami, and got in one more film before he passed on in 2020. It proved to be his most dreamlike work since House. Just what’s meant to be real, imagination or movie in Labyrinth of Cinema is never clear, nor is it meant to be. It’s a three-hour cycle through genres, tones, and styles with that familiar antiwar theme. With that sort of framework, it’s bound to be an uneven ride, but it’s fun to try and keep up with what’s really happening. But there’s no effort needed to see how much Obayashi loved his medium, and his belief that it could be a force for good in the world. While Hanagatami was a more even and impressive film, Labyrinth of Cinema gave Obayashi a chance to go out on a more optimistic note.