“Here there be monsters,” declared the old warning, and in this case, they’d be right. This is a catalogue of classic movie monsters, the creatures that kept whole generations awake at night and represented fears and anxieties that still plague humanity today. Classic monster movies may not have been as violent or sensual as the monster movies of today but that doesn’t mean they don’t still have the power to captivate and terrify. Besides, all the horror movies people love today wouldn’t exist if these movies didn’t lay out all the groundwork.

Of course, not all horror movies are monster movies. Monster movies are movies about unnatural creatures, usually stemming from supernatural folklore or science fiction, that threaten us with physical or psychological violence. They are the enemy without, although they often represent the enemy within. They are sometimes inexplicable but often sympathetic. Like the rest of us, they’re just trying to survive. If they have to drink human blood or turn into a man-eating panther to do it, then that’s just what they have to do. You can feel their pain all they want, but when they come calling… run! Run for your lives!

Choosing the parameters for what counts as a “classic” monster movie was a lot trickier than choosing the parameters for what counts as a monster. Ultimately we settled on the following: the films must be of excellent quality, with some extra consideration awarded for films with a lasting artistic or cultural influence. The films must also have been released in the year 1960 or earlier. (Sorry, Mr. Sardonicus, but we had to set the cut off somewhere.)

So get the fireplace going in your ancient gothic castle, and fire up the Tesla coils… it’s time to explore our picks for The 25 Best Classic Monster Movies!

And for even more spooky horror lists, check out our rundowns of the best vampire, zombie, and werewolf movies.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

Although films about murders and monsters had been made before, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is frequently considered, as Roger Ebert put it, “the first true horror film.” It’s not merely a catalogue of gruesome events, it’s a deep dive into a fragmented and terrified mind, in which a malevolent hypnotist named Caligari (Werner Krauss) manipulates a sunken-eyed somnambulist named Cesare (Conrad Veidt) into committing murders.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a landmark masterwork of German Expressionism, a filmmaking style that pioneered the use of impossible imagery to evoke powerful reactions in the audience. It looks as though Cesare and his victims are wandering through black-and-white, borderline abstract paintings because they really are, and the impact is maddening and terrifying. Caligari is one of the most influential films ever made, especially in the horror genre; practically every monster movie that follows owes this film - which still has the power to unnerve - a debt of gratitude.

Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (1922)

Another German Expressionist masterpiece, F.W. Murnau’s unofficial adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula features one of the most disturbing creatures ever captured on film: the ratlike Count Orlok (Max Schreck), whose drooping, unnatural features hint at centuries of living outside of the light, feasting on unclean things. Equally unsettling in the light or in stark shadow, the floating visage of Orlok is enough to permeate anybody’s nightmares.

But also, Nosferatu is a captivating, dreamlike motion picture. Following the events of Stoker’s Dracula very closely - so closely, in fact, that the producers were successfully sued, and nearly all copies of the film were destroyed - it’s a tale of death come to life, infecting the innocent and overcoming society. The movie itself is practically a plague, and the only cure is to make it all the way to the miraculous ending.

The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

No article about classic movie monsters would be complete without the inimitable Lon Chaney, Sr., the aptly-named “Man of a Thousand Faces” who starred in a long series of disturbing silent horror movies. The Phantom of the Opera may very well be his masterpiece. The adaptation of Gaston Leroux’s 1910 horror novel about a madman stalking a beautiful ingenue from his subterranean lair beneath the Paris Opera House is a lavish production, filled with stunning sets and vast crowds. It would be romantic if it wasn’t so damnably creepy.

But most of all, The Phantom of the Opera is a delivery system for Chaney’s makeup effects wizardry. The Phantom, shrouded in masks and shadow for half the film, serenades his lady love in his catacombs. She cannot resist the urge to see what her mysterious benefactor looks like, and unmasks him suddenly as he plays the organ. Chaney’s face erupts in shock and horror, as horrified as the audience. But whereas we recoil from his gruesome, corpse-like image, he’s reeling from the sudden act of betrayal. He was beautiful until we saw him, and now that he’s been seen he will continue to play the monster.

Dracula (1931) & Drácula (1931)

One of the most iconic “Universal Horror Movies” - a cavalcade of tragic and beautiful and frightening creatures, whose blockbuster franchises kept the studio alive during the Great Depression - was Tod Browning’s Dracula. But it was also George Melford’s Drácula, a Spanish language version of the film shot on the exact same sets as Browning’s version, at night, after the day crew went home. They are two halves the same classic movie: one brilliantly acted, the other brilliantly filmed.

Browning’s Dracula stars Bela Lugosi, who gives an iconic, sensual, piercing performance as the Transylvanian immigrant who drinks human blood threatens to steal England’s women away. It’s a quiet film, and frankly a little stodgy, and it’s mostly anchored almost entirely by Lugosi’s brilliance. In contrast, Melford’s Drácula is stylishly presented, immersive and suspenseful. And although Carlos Villarías is a fine Dracula, the character doesn’t come across as alluring or tragic as it does when Lugosi plays him.

Watch both classic versions of Dracula back-to-back for an illuminating experience, and to achieve the ultimate appreciation for one of cinema’s most enduring early monsters.

Frankenstein (1931)

Director James Whale pushed the boundaries of horror cinema with his adaptation of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein. Although the film strips Shelley’s narrative down to its base components and makes some notable edits and changes, it captures the ghoulish evil of amoral scientific progress and the unexpected beauty of the warped and the weird. Colin Clive stars as Dr. Frankenstein and Boris Karloff, played credited as only “?”, plays his undead monster, who breaks free of his uncaring father and pursues love elsewhere, only to be martyred for his trouble.

It’s a dynamic production, full of lightning and shadow, and Karloff is absolutely magnificent as the Frankenstein Monster. His initial reveal isn’t a man, it’s a corpse that just happens to be walking, as dead inside as it is alive outside. Watching him slowly gain consciousness - to late for his fearful, rejecting “father” to notice - is a master class in subtlety, and watching Whale use Karloff’s transformation and innocence to weave a tale of tragedy and terror is absolutely hypnotic.

The Mummy (1932)

Karl Freund’s Universal Monster classic The Mummy capitalized on zeitgeist of Egyptian archaeology in the early 20th century, as well as the monumental success of Dracula. To tell this original tale of an undead mummy who falls in love with the reincarnation of his long-dead lover, Freund heavily evoked Browning’s blockbuster horror movie in its characters and storyline. The imitation is more than just flattery: Freund’s movie is arguably the superior version of the tale, with sensuality and romance and suspense abound.

At the heart of it all is, once again, Boris Karloff, who only spends a few short moments in the iconic death shrouds. For most of the film he’s a respectable gentleman, soft-spoken and enticing, who is so desperate to find a connection outside of the boundaries of terrible time that he’ll do nearly anything to make a young woman, played by the fantastic Zita Johann, remember who she once was and could be again. The mythology may be off but the emotional core and the thrills are just right.

Island of Lost Souls (1932)

There has been no greater cinematic adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau than Erle C. Kenton’s Island of Lost Souls. Featuring creature makeup well ahead of its time, and a deliriously sinister performance from the always-amazing Charles Laughton, it’s a harrowing tale of colonialism and eugenics run amok, as potent today as it was nearly 90 years ago.

Laughton plays Dr. Moreau, a scientist who lives on an isolated island where he transformed animals into humans using extreme and torturous vivisection techniques. Once created, he abuses them and mocks their inferiority, and keeps them under his thumb through the threat of violence and the creation of a new, oppressive religion. When a human castaway arrives on his island, Moreau decides to use him as breeding stock. It’s terrifying but absolutely captivating, and Laughton smugly shed off every shred of his humanity in an all-time brilliant horror performance.

King Kong (1933)

King Kong is one of those milestone movies that divide cinema in half. There are movies that came before Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack special effects masterpiece, and there are those that came after this astounding spectacle proved that, in a theater, anything is possible. In an era where films like safari films Trader Horn were enormous hits, King Kong tells an unusually meta tale about a movie crew that ventures into the unknown wilds and discover dinosaurs and, astoundingly, a gorilla the size of a building.

Brought to life by stop-motion maestro Willis O’Brien, Kong is more than just a frightening monster. He’s a fully realized character, full of love, anger and sadness, who fights Tyrannosaurs to rescue the human woman he loves (Fay Wray, always wonderful) and plows haphazardly through New York City after he’s abducted by his oppressors. He’s not evil, he’s confused and frightened. In the end, it is stunning to watch him vanquished, but there’s no victory. Although elements of Kong’s story are (at best) dated, the core storyline about man’s hubris destroying an innocent creature will always be powerful.

The Invisible Man (1933)

Classic horror movie monsters don’t get much less sympathetic than Dr. Jack Griffin, the aptly-named Invisible Man. In this adaptation of another H.G. Wells classic, Claude Rains plays a scientist who makes himself completely disappear, but after an initial flirtation with curing his strange affliction, he goes mad with power and embarks on a spree of murder and terrorism.

Rains is a riveting villain in The Invisible Man, and his character is brought to life through visual effects so convincing that it’s hard to believe they were possible before CGI. What’s more, Whale seems to revel in telling a story about unapologetic evil, and expects the audience to delight in watching this chaos unfold, even more than he wants you to cheer for Griffin’s defeat. It’s a subversive, technically ingenious horror thriller.

Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

James Whale digs up the corpse of Frankenstein for a sequel that many believe, and with good cause, to be superior to the original. Bride of Frankenstein resurrects elements of Shelley’s novel that were excised from the original, and finds Karloff’s monster forcing his creator to build him a bride, to cure his unending loneliness. Tragically, the monster learns the hard way that you can make a person out of sewn-together cadavers, but you can’t make them love you.

Bride of Frankenstein pulls out all the stops, with a film that’s as ghoulish as it is funny, with bizarre special effects sequence and intimate character work. What’s more, Whale uses the veneer of the fantastical horror genre to directly confront topics that Hollywood considered completely taboo back in the days of the Production Code. Bride of Frankenstein playfully incorporates homosexuality, blasphemy, and necrophilia into what looks like mainstream entertainment. It’s a lavish feast for the senses, and an absolute smorgasbord for the mind.

The Wolf Man (1941)

Lon Chaney Jr., whose father was the most famous horror actor of his generation became an iconic movie monster himself in the classic werewolf tale The Wolf Man. Chaney plays Larry Talbot, who returns to his family home in Wales to reconnect with his estranged, emotionally distant father John (Claude Rains). It seems as though his life might be turning around, he’s even met a nice girl in town, but he’s attacked in the fog, bitten, and discovers to his horror that he’s transforming into a murderous creature.

The Wolf Man features iconic time-lapse effects, forcing Chaney to remain completely still for hours as makeup was applied to him in stages. But although the look of the title monster is unforgettable, it’s Chaney who makes this movie unforgettable. Larry Talbot is one of Universal’s most tragic monsters, who is consciously aware of his plight and utterly helpless to do anything about it. And his practically unrequited relationship with his father only makes the film’s brutal finale all the more heartbreaking. The Wolf Man is Lon Chaney Jr.’s finest hour.

Cat People (1942)

Jacques Tourneur’s smart, sensitive and impressively progressive Cat People stars Simone Simon as a Serbian immigrant who believes that if she will turn into a panther if she is enraged, or sexually aroused. And yet her American boyfriend ignores all those obvious red flags and insists on marrying her anyway, thinking she’ll get over all her “backward” superstitions and feminine anxieties if she just finds herself the right man. Don’t worry, he’ll be proven wrong. Very wrong.

Cat People and its underrated sequel, Curse of the Cat People, ostensibly play like a monster movie in which a heroic man is threatened by dangerous women. But Turner knows who the real monster is, and gives Simone Simon all of the film’s most sensitive moments. Her tragedy is being ignored because it’s inconvenient to the man who wants to possess her, and anyone who gets eaten by a panther in this movie (or even almost does) almost certainly deserves it.

But beyond its satisfying allegories, Cat People is also a satisfyingly produced and influential thriller. It was this film that introduced into the horror filmmaking lexicon the gag called “The Lewton Bus” (named after producer Val Lewton), in a scene where suspense mounts, and it looks like someone is about to be murdered, only for them to be scared by something innocuous instead. In Cat People, it’s a bus. Ironically, in many of the other horror films that borrow this gimmick, it’s a cat!

I Walked with a Zombie (1943)

Lots of classic horror movies are based on classic horror novels, but Jacques Tourneur’s horror classic I Walked with a Zombie is based on Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. All they did was turn the madwoman in the attic into a literal monster. And somehow, instead of feeling tacky or gimmicky, it works. I Walked with a Zombie is one of the most unusual and emotional monster movies of its era.

A nurse named Betsy (Frances Dee) travels to the Caribbean to care for the wife of Paul Holland (Tom Conway), who suffers from a mysterious ailment. She has completely lost her sense of willpower. Betsy tries everything in her power to cure Paul’s wife but she’s running out of alternatives. It’s possible, as the residents of the island believe, that she’s no longer alive, and is instead the victim of a supernatural ritual.

Though mysterious and strange, Tourneur’s film is also sensitive and tender. That’s what happens when you turn one of the great gothic romances into one of the great monster movies!

The Thing from Another World (1951)

Popular opinion dictates that John Carpenter’s remake of The Thing from Another World is superior to the original, and that may actually be true. There’s no denying the terrifying isolation and astounding practical effects in the 1982 version of this sci-fi thriller. But there’s also no denying that the original is still scary and effective, and smarter than most monster movies of its era.

Set in an isolated outpost in Alaska, a group of scientists investigate a mysterious crash landing in the tundra, and uncover amongst the wreckage an alien being. The creature escapes from the ice and begins draining the blood from its victims, in an effort to bring more of its plant-based organisms to life. The bizarre beast and smart sci-fi trappings make The Thing from Another World stand out, but the uncredited direction from the great Howard Hawks also lends the film’s characters and dialogue a dynamic quality that transcends b-movie expectations. It’s clever, it’s scary, and it’s classy as hell.

Invaders from Mars (1953)

From Oscar-winning production designer and wildly underappreciated director William Cameron Menzies comes a child’s nightmare brought to vivid life. Invaders from Mars plays like an American, technicolor German Expressionist film, as the world around its young hero comes crashing in around him after a flying saucer lands in his backyard and begins taking over the minds of every adult in town.

Surreal and frightening, Menzies uses impractical design - like a police jail cell that gets smaller in the back - to highlight just how alone and helpless Invaders from Mars’ protagonist is. By the time young David McLean (Jimmy Hunt) finds himself inside the alien spacecraft, all bets are off, anything can and will happen, and no image is too bizarre to be realized. And by the time the film concludes, with an ending that hardly anyone could predict, you might also begin to wonder if you’re losing your mind!

The Twonky (1953)

Largely forgotten and almost completely unavailable, The Twonky is one of the great unsung horror comedies of the era. Hans Conreid (the voice of Captain Hook from Disney’s Peter Pan) stars as a fusty professor whose wife goes on holiday and leaves him alone with their new television. But it’s more than just a television. It’s a high tech artificially intelligent entity that walks around the house of its own volition, saps the free will out of his students and drives him gradually mad.

Too funny to be scary but too subversive to be ridiculous, The Twonky plays off of every generation’s anxieties about the next generation’s advancements. New technologies that turn us into zombies, rob us of our privacy and steer us directly into dystopia? That’s not paranoia, that’s just a Twonky. It’s as relevant a story now as it ever was, and writer/director Arch Oboler’s bizarre, almost Seussian sensibilities make The Twonky timeless enough to still make an impact.

The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954)

The last of the great Universal Horror monsters came wriggling out from beneath the waters. The Creature from the Black Lagoon tells the tale of a scientific expedition into the Amazon, where geologists have uncovered evidence of an ancient race of aquatic humanoids. Little do they know that at least one of the creatures still exists and is staring at them from below, and becoming obsessed with one of their number, Kay (Julie Adams).

The Creature attacks and violence breaks out, and that’s all well and good. It’s the oddness of the monster and the atypicality of its environment that make The Creature from the Black Lagoon linger. Unlike many Universal Monsters, who either considered themselves upper class, or were slow-moving cadavers, the Gill-Man is an elegant creation who moves swiftly in the water, and whose humanity is relatively in question. It’s a unique cinematic curiosity, as gorgeous to look at as it is dangerous to touch.

Gojira (1954)

Ishirō Honda’s sci-fi/horror classic Gojira wasn’t the first film about a giant monster awakened from the deep sea depths by nuclear radiation - The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms had already come out the year before, featuring astounding Ray Harryhausen effects - but it is the film that elevated the strange concept into a deep and powerful allegory. Gojira puts a fantastical bent on real-life horrors of nuclear proliferation and environmental fallout, giving the filmmakers just enough distance from the tragedy to explore related themes in challenging ways.

Gojira opens with one seemingly natural disaster after another, the aftermath of Gojira’s sudden rise from the waves, until finally, the monster appears, as destructive and unthinkable as a mushroom cloud would have been just one generation earlier. A far cry from the entertaining sequels that would follow, Ishirō Honda’s original is a sobering depiction of urban annihilation, in which the only way to save Japan might very well be to engage in the same perversions of science that lead to the creation of an atomic bomb in the first place. Powerful allegorical filmmaking, and the launchpad for the incredible and prolific kaiju genre.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

America’s fear and ironic embrace of conformity were captured like lightning in a bottle inside Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers. The film stars Kevin McCarthy as a doctor in a small Californian town, where people are gradually being replaced by alien duplicates who mimic everything about the original except their flaws. It’s a nearly impossible conclusion to come to, the kind of deranged paranoid fantasy that could stem from reading too much propaganda. And yet it’s happening, inside the film and - it could be argued - in the hometown of anybody watching.

Whether Invasion of the Body Snatchers satirizes the cultural conformity of American culture in the 1950s, or America’s fears of dystopian control as a result of the Red Scare, it’s a masterpiece of low budget genre filmmaking. The actors are convincing and the scenario is frightening no matter how you interpret the movie’s themes. It’s so universal that Invasion of the Body Snatchers has been remade multiple times, usually very well, as future generations discovered that the anxieties evoked by Siegel’s sci-fi/horror classic never go way. They simply mutate into another strain of fear.

Forbidden Planet (1956)

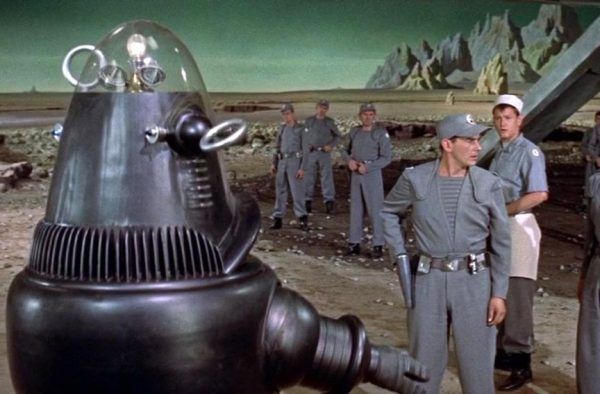

Halfway between Shakespeare and Star Trek there lies Fred M. Wilcox’s sci-fi/horror classic Forbidden Planet. Loosely based on The Tempest, and heavily influencing Gene Roddenberry a decade later, the film stars Leslie Nielson as the captain of a futuristic space ship assigned to investigate a missing expedition. What they find is a planet populated by a seemingly mad scientist, Dr. Morbius (Walter Pigeon), his lonely daughter Alta (Anne Francis) and their powerful robot Robbie (playfully credited as himself).

Dr. Morbius warns the captain of the planet’s dangers, which manifest in the form of an invisible leviathan that attacks the ship every night, and only reveals its horrible form when it’s captured in an energy field. But there’s more than meets the eye (or doesn’t), and Forbidden Planet gradually reveals itself to be an altogether new kind of monster movie. Wilcox’s film is gorgeously realized, and full of fantastical sets and way out ideas which, in the decades that followed, became sci-fi mainstays.