Face it: we already live in the future. We’ve got robot cars and computers in our pockets and Large Hadron Colliders and we aren’t stopping anytime soon. The sci-fi movies of yesterday are still wonderful but the sci-fi movies of the 21st century have face an impossible challenge: the future we could envision in the year 2000 is, in many ways, radically removed from the future we envision today, and many of the technologies we now take for granted were a pipe dream only 20 years ago.

So it’s fascinating to explore the last 20 years of science fiction motion pictures and watch filmmakers struggle to stay on the cutting edge of the cutting edge, always one step into the future, and (hopefully) never ruined by the next big leap forward. The best sci-fi movies of the 21st century (so far) have found ways to connect their big, futuristic ideas with contemporary and/or universal concerns. Our anxieties about governments, technology, artificial intelligences, unthinkable new species and our own, potentially questionable natures fuel the fiction we write about what’s in store for us tomorrow.

And these are the best works of cinematic fiction that have been told about our tomorrows, today.

Battle Royale (2000)

Before The Hunger Games made blockbuster money pitting children against each other in a game of death to prop up a dystopian society, Kinji Fukusaku did it with even more acidity and ruthless commentary. Battle Royale is about a whole class of teenaged troublemakers who are kidnapped and taken to a deserted island, where they are outfitted with explosive collars and told only one of them can survive the weekend. The unthinkable situation drives some students mad, drives others to explore ingenious alternatives, and ultimately drives the film’s bodycount to terrible extremes.

Action-packed but too unfathomably tragic to be mistaken for escapism, Battle Royale is one of the most shocking, controversial and effective dystopian movies in many decades. Its sequel, the underappreciated Battle Royale II, is also worth discovering: it significantly alters the original premise but seems to cannily predict a future where politically active young people are viewed by the establishment as the dangerous threat to the status quo.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

Originally planned as a direct collaboration between Steven Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick, and finished by Spielberg just two years after Kubrick’s death, A.I. Artificial Intelligence really does lie directly at the intersection of the iconic filmmakers’ sensibilities. It’s the story of a lifelike robot child, played by Haley Joel Osment, who is programmed to love but is rejected by his would-be mother, and since he was never programmed to understand rejection, embarks on a futile quest to be a decent, human child.

Inherently emotional but objectively cynical, A.I. Artificial Intelligence takes place at the moment when technology has only just begun to surpass the limitations of the humans who invented it, and illustrates how the introduction of a new lower class of people would be misunderstood and abused by their creators. The conclusion has been accused of maudlin sentimentality, and perhaps it is, but Spielberg can surely be forgiven for loving the hero of A.I. enough to cut him the tiniest amount of slack.

Donnie Darko

Teenagers often feel like they’re helpless in the face of uncontrollable forces, but usually that’s just hormones. In Richard Kelly’s cult classic Donnie Darko, it’s actually a hallucination in a rabbit costume and, probably, some form of time travel. Jake Gyllenhaal stars as the title character, a disenfranchised teen who seems to be suffering from a severe mental illness, but whose visions and inexplicable deeds seem more than human, and yield results that suggest he knows things that nobody could possibly know.

The science of Donnie Darko is oblique and challenging, and you could turn your brain around 180 degrees just trying to keep them all straight. But the important thing is the way Kelly’s film illustrates adolescent aimlessness as a strange form of wisdom. Coming up with complicated reasons for actions which otherwise could be written off as a teen angst gives daily life a creepy kind of authority and power, as though the existential confusion we all feel could be easily solved… so long as we had a sinister rabbit to tell us what to do.

S1m0ne (2001)

Largely overlooked in its release, but eerily prescient nevertheless, Andrew Niccol’s bitter sci-fi comedy S1m0ne stars Al Pacino as a struggling filmmaker who acquires a fully digital, 100% lifelike actor and proceeds to pass her off as the real thing. In the process he reinvigorates his career and transforms the entire entertainment industry into an updated version of The Emperor’s New Clothes, where everyone supports the lie that “Simone” is real just to be a part of her success story.

With digital technology making leaps and bounds since S1m0ne’s release, and filmmakers now threatening to resurrect dead actors via CG performances, the questions Niccol raises about how the entertainment industry would treat digital performers, and whether new technologies would make filmmakers retreat back to old-fashioned techniques just to reclaim the humanity of the art form, are more relevant than ever. But it’s a clever, intriguing and funny film whether or not you’re part of the industry.

Minority Report (2002)

Spielberg made another sci-fi classic in the early 2000s with Minority Report, an adaptation of a Philip K. Dick story about a future where murders are prevented before they occur, but the would-be murderers - who technically haven’t committed a crime yet - are prosecuted exactly the same. Tom Cruise stars as a detective who discovers that he’s been accused of pre-meditated murder and tries to clear his name by finding a “minority report,” which would make a case for at least one alternate future in which he does nothing wrong.

Minority Report is a bold and exciting chase film about a wrongly accused man, and at its core Spielberg treats the story like a Hitchcockian thrill ride. He also packs the film with updated concepts in futurism, and successfully predicts at least some recent developments, like digital advertising targeted specifically at individual consumers based on their previous activities. But best of all, Spielberg’s film tackles the serious moral and ethical ramifications of keeping the world peaceful at the cost of rational justice. It’s one of the smartest and most innovative blockbusters of the century so far.

28 Days Later (2002)

The zombie genre had been popular for many years before Danny Boyle came around to it. But Boyle, working from a screenplay by Alex Garland (who would go on to write and/or direct several other movies on this list), effectively reinvented the idea with 28 Days Later. It would have been enough that Boyle’s film popularized the idea of zombies running, instead of merely shambling, infusing 28 Days Later with an adrenaline junkie sensibility that completely changed the horrifying dynamics. But he also filmed the whole thing with consumer grade video cameras, infusing an otherwise ridiculous concept with a docudrama realism that was impossible to disregard.

28 Days Later pushed the post-apocalyptic zombie virus genre forward, making way for Zack Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead remake, the comic book series The Walking Dead and beyond. It’s also a ripping good sci-fi/horror yarn in-and-of itself. Cillian Murphy stars as a comatose man who wakes up four weeks after the zombie apocalypse, and his journey takes him from claustrophobic strife to gleeful shopping sprees to horrifying militaristic dehumanization. Effectively, 28 Days Later is a modern day remake of Romero’s original trilogy - Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead - compressing the history of the genre into a new, modern package that re-legitimized the whole concept and became, in the process, one of the most influential films of the century so far.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

If it was possible to manipulate the human mind at will, what would we use that technology for? Michel Gondry’s bittersweet love story stars Jim Carrey, giving arguably his finest performance, as a man who learns his wife has erased every memory of their relationship to help her move on, and decides to undergo the procedure himself to rid himself of extraneous pain. Where Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind goes from their absolute, maddening brilliance, as we witness all those memories getting warped and erased from the inside of the protagonist’s mind, as he fights - and repeatedly fails - to rescue the happy memories from the seemingly unstoppable torrent of erasure.

Co-written by Gondry and Charlie Kaufman, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is a beautifully realized sci-fi story that capitalizes on all the visual tricks in Gondry’s extensive, quirky arsenal. But best of all it uses all that futuristic technology and ingenious imagery to illustrate, in an extremely specific way, a universal human experience: the desire to rid ourselves of our pain and trauma often overshadows our even greater need to learn from past mistakes and cling to the positivity that shapes us into better, more loving people. Intensely soulful and cinematically distinctive, Eternal Sunshine is another modern classic.

Primer (2004)

Time travel is, in even the silliest of sci-fi movies, absurdly complicated and difficult to wrap your head around. Rather than shy away from the complexities of travel through time and, potentially, screwing up the past, present and future, writer/director Shane Carruth’s fiendish low-budget thriller Primer dives headlong into the impossible, weaving a narrative about two scientists who invent a means of traveling through time and discover - gradually, and to their horror - that they may have already used it.

To watch Primer for the first time is to get completely lost in a sea of details and paradoxes, to the extent that after you watch it you may need to watch an online primer about the plot of Primer. But like all the best puzzles there’s no greater reward than solving it, because once you unravel Carruth’s labyrinthine storyline you realize that it’s always made sense, it just took a mad genius to figure out it.

Children of Men (2006)

It’s the near future, and no new children have been born on the planet earth in decades. With no explanation or cure in sight, it seems as though humanity only has one generation left before perpetuating the species becomes impossible. Alfonso Cuaron’s pulse-pounding Children of Men never gets into the hard science of why the human race is imperiled. It’s more concerned about what an undeniable sense of impending doom would do to the world at large, and how far we’d go to save the planet or find an excuse to keep making the same old, horrible mistakes.

Children of Men stars Clive Owen as a civil servant who must protect a refugee who, somehow, has given birth to the first baby in two decades. Along their perilous journey Cuaron uses many of the bravura cinematic techniques he’s been developing throughout his long career, with one-take action sequences and digital trickery to transform a seemingly intimate story into a gigantic, all-or-nothing mini-epic about the fate of the world. Exquisitely crafted and extremely intense, Children of Men is a stunner.

Idiocracy (2006)

After mercilessly skewering turn of the century office drudgery in Office Space, filmmaker Mike Judge set his sights on the future, where - despite everything Star Trek tried to preach to us - it sure as heck looks like everyone is getting dumber. Idiocracy stars Luke Wilson as an exceptionally mediocre everyman who’s cryogenically frozen and wakes up in a distant future where society has devolved into dunderheaded sociopolitical and economic chaos, in which the government’s knowledge of environmentalism is so abominably backward they’ve been using energy drinks on plants instead of water.

At its best, Idiocracy doesn’t seem all that far-fetched. At its worst its a cynical but laugh-out-loud sci-fi comedy that turns every expectation we have about futuristic stories upside down. Judge mercilessly lampoons contemporary society by taking our most illogical and self-destructive tendencies to their logical extremes, wagging his finger at us in a way that also makes us giggle.

Paprika (2006)

The last feature film of the late, lamented animation genius Satoshi Kon tells the story of a near future in which a young woman uses experimental technology to project herself into other people’s dreams. But whereas our hero uses the technology to heal the human mind, someone else is using it to tear open the membrane between the waking world and the human imagination, transforming reality into an absurd, malevolent, chaotic nightmare.

Paprika is one of the most dazzlingly realized motion pictures to ever take place inside the human brain, with imagery that Christopher Nolan would eventually borrow wholesale for his dynamite - but comparatively superficial - psychic heist thriller Inception. Satoshi Kon uses dream imagery as an allegory for filmmaking, and vice-versa, as he teaches audiences concepts about visual storytelling only to subvert them later, in chase sequences that race from one fantasy into another, one movie into another, and ultimately between abstract reality and concrete daily life. Paprika is breathless to the nth degree, and impressively realized at every level.

A Scanner Darkly (2006)

In Richard Linklater’s sprawling psychedelic opus Waking Life, the filmmaker use rotoscoping techniques to keep audiences off-kilter, in a dreamlike state, and prone to new ideas and suggestions. It only makes sense that he would adapt that same filmmaking process for a sci-fi story as trippy as A Scanner Darkly, based on Philip K. Dick’s dystopian drug-fueled paranoid fantasy about a future America that’s under perpetual surveillance and also, largely, addicted to hallucinogenic drugs.

The film stars Keanu Reeves as an undercover narcotics officer trying to learn who’s supplying these super drugs, but his journey gets sidetracked by bizarre acquaintances, betrayals and his own growing addiction to psychotropics. Although A Scanner Darkly plays in familiar genre tropes the film has no interest in conventional thrills; it’s about getting lost, in an environment that makes losing yourself increasingly easy and tempting. The bizarre and ever-shifting technological, political and chemical environments in which we find ourselves - perpetually watched, perpetually lonely - are more than enough crisis to keep Linklater’s bizarre and entrancing sci-fi classic from ever losing its own way.

Sunshine (2007)

Danny Boyle had already reimagined the zombie genre with 28 Days Later, so reinventing the environmental disaster movie was a logical step. Sunshine follows a group of scientists as they venture to the sun itself, in the middle of our solar system, in an attempt to reignite it before it dies and destroys all human life in the process. As a concept it’s not entirely dissimilar from Jon Amiel’s ludicrous sci-fi disaster epic The Core, but in execution - thanks, again, in large part to a screenplay by Alex Garland - it’s an intense men-on-a-mission movie, filled with wonder and anxiety about the vastness of the universe, and the awesome power of the life-giving ball of fire that sustains us all.

Sunshine eschews the fun-and-games nonsense the disaster genre, the comic relief characters and the eye-popping action sequences, and considers just what an overwhelming assignment saving the world would really be under such impossible circumstances. The crew of the ship has personal conflicts but compartmentalize in the face of every crisis, never losing sight of their mission. There’s a nobility in Sunshine, and a tragedy in the human frailty that emerges at the very end, that suggests that even the most entertaining Irwin Allen/Roland Emmerich spectacle is doing the genre a disservice; if the world really is ending, maybe we should exert all our energy saving it, instead engaging in maudlin melodrama and crowd-pleasing gags.

Timecrimes (2007)

Describing Nacho Vigalondo’s wondrously complex independent thriller Time Crimes is an incredibly tricky proposition, because the greatest crime of all would be revealing how it unfolds. Suffice it to say this low-budget mindbender is about time travel, and it is certainly about crimes, but it’s also the story about a seemingly normal man who stumbles into a plot that is completely beyond his comprehension and becomes an absolute victim of looping timelines and nonsensical fate. Our “hero,” if you can call him that, knows that events in the future have to happen but only because he knows they happen, not because he has any idea why, or any motivation to carry them out.

Most stories about time travel are about taking control of our destinies, or fixing past tragedies. Vigalondo’s incredibly smart film is about becoming a victim of time travel, where nothing you do matters but you have to do everything anyway, like a nightmarish chronology-jumping labyrinth of completely blind fatalism. The solution isn’t about saving the day, it’s about getting through a massive “to do” list, and earning your way out of the overwhelming chaos of life itself.

Iron Man (2008)

Lots of superhero movies are, at their core, also science fiction movies, but the first Marvel Cinematic Universe film - which takes place at a time when the MCU’s fictional reality seemed relatively real, and the introduction of superheroes was a major revelation - is probably the most straightforward example. Iron Man isn’t just a movie about a guy in a cool costume fighting supervillains. It’s rooted in the fundamental irony of Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, Don Heck and Jack Kirby’s original character, an arms manufacturer who is forced to turn himself into a weapon and experience firsthand the moral complexities of warfare, and come to terms with his own culpability in making the world a dangerous place.

A villain who sees the error of his ways and becomes a hero, using futuristic technology to transform weaponry from a heartless tool into a fundamental extension of the person making the decision whether or not to engage in violence. Jon Favreau’s film is focused and intelligent and, thanks to the spectacular casting of Robert Downey Jr. - a charismatic actor who was himself experiencing a renaissance after troubled times - impressively humane and likable. Even if the rest of the MCU hadn’t come to pass, the original Iron Man would still stand out as an excellent, entertaining blockbuster about how technology makes the world, and specifically the world at war, go ‘round.

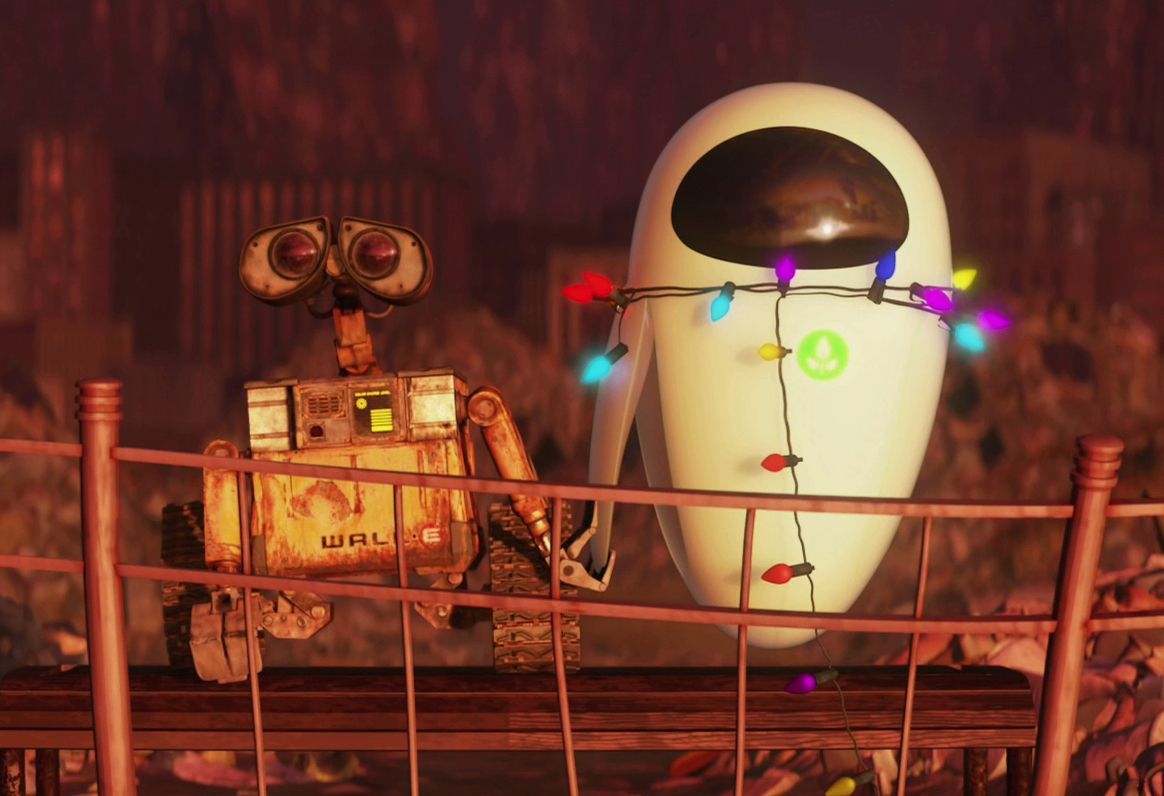

WALL-E (2008)

One of Pixar’s most ambitious productions, to this day, is an epic sci-fi comedy romance parable about a little trash compactor robot who learns how to love and, simply by virtue of his unexpected existence and determined binary-coded heart, saves all of humanity. WALL-E is an absolute wonder of a movie, daringly conveying the first half of the story in almost dialogue-free silence before rocketing into outer space and making stern condemnations about how consumerism and blind faith in social systems can easily drive society into nearly absolute inertia.

On top of all that headiness, Andrew Stanton’s film is also astoundingly funny, genuinely romantic and exciting to witness. It’s easy to take for granted, now that the film is a beloved success and a staple of the Pixar canon, but WALL-E takes gigantic narrative risks throughout the production and constantly adjusts its sense of wonder and scale and color to match the evolving worldview of someone letting love drive them into brand new, daunting places, and transform them into the kind of person - or robot - that nobody could have ever predicted. It’s unbelievably beautiful.

Avatar (2009)

There are parts of James Cameron’s ultra-mega-super-blockbuster sci-fi spectacular Avatar that, frankly, seem rudimentary. It’s a tried-and-true story about a generic colonial hero who immerses himself into another culture, becomes their greatest hero, and fights superficial bad guys who only need to make a ruckus in the first place because they’re looking for an absurdly named MacGuffin called “Unobtainium,” for crying out loud.

But the genius of Avatar is that Cameron knows those reductive storytelling tropes are ingrained into the DNA of practically every action-adventure movie on some level, and by backtracking into that simplicity he is able to gives his grandest ambitions - a distinct, beautiful alien world brought to life by groundbreaking CGI and game-changing 3-D filmmaking - the whole spotlight. The criticisms lobbed at Avatar’s storytelling are wholly deserved but as a fully-realized artistic vision, one that goes beyond plotting and characterization, Avatar does what few other sci-fi blockbusters can, and send audiences on a truly immersive journey into the fantastic.

District 9 (2009)

Neill Blomkamp adapted his depressing, pointed sci-fi short film Alive in Joburg - about an alien species that crash-lands in South Africa, only to become oppressed by a modern apartheid - into a sprawling and satisfying action epic with big ideas and stunning visual effects. The film stars Sharlto Copley as a corporate yes-man tasked with relocating the impoverished aliens, called “Prawns,” but a chance encounter mixes his DNA with the alien species. Now he’s on the receiving end of government experiments and institutional dehumanization. Only now does he actually give a damn about principles. Only now is he willing to fight against oppression.

District 9 is a smart action-thriller full of impressively realistic CGI, but the film’s most impressive quality is the way it never completely forgives its protagonist. He’s an enormous hypocrite who is, in a very Twilight Zone sense, getting the ironic and troubling fate he deserves. District 9 isn’t letting anyone off the hook, including the audience, and uses its sci-fi violence to tell an angry story about serious issues which should make everybody furious. It’s got all the hell-raising rhetoric and incredible action we love in sci-fi classics like RoboCop and Total Recall. There’s a good reason it’s one of the few sci-fi films ever nominated for Best Picture!

Gamer (2009)

The horrifying dystopian vision of humans hunting humans for sport takes on a new dimension in Neveldine/Taylor’s energized and embittered sci-fi thriller Gamer. The film stars Gerard Butler as a convicted felon on death row who has a slim chance to earn his freedom by taking part in modern gladiatorial combat for the entertainment of the masses. The twist is, he’s not in control of his own body: he’s being controlled by a teenaged video game enthusiast, who gleefully uses our hero to slaughter other criminals for fun and profit.

Gamer concocts incredibly exciting action sequences around this fascinating twist on video game mechanics, and also sets up a parallel world, not unlike The Sims, wherein real people are paid to live fantasy lives - decadent, sexual, violent - for the pleasure of the gamers sitting at home. Deeply cynical but profoundly clever, Gamer functions as a brainless action spectacle but also as a sweeping judgment about the dangers of disengaging emotionally with our fiction. The characters we watch or control have as much humanity as we allow them to have, and if we deny them that significance, maybe that says more about our collective lack of empathy than anything else.

Moon (2009)

Sam Rockwell gives a career-best performance in Moon, a sci-fi drama that’s modest in scale but big on ambition. The directorial debut of Duncan Jones finds Rockwell on a lunar colony all by himself, with only a smiley-faced robot to keep him company. His three-year shift is almost over when an unexpected accident uncovers… something deeply disturbing, that makes our hero question his job, his value, and the nature of his reality.

Moon is a sci-fi character piece, not a plot-heavy thriller, so to reveal hardly anything about the story would be to reveal too much. It’s a masterful debut by Jones, who keeps the small number of locations and introspective narrative entertaining and absorbing throughout, and a tour de force by Rockwell, who carries the whole film on his shoulders with insight and aplomb. All this impressive artistry contributes to a witty and borderline profound tale about human worth.