For decades, films have placed emphasis on romantic love, while stories about platonic love have often taken a backseat. Thankfully, in recent years, films about the nuanced complications and intimacy of friendship have seen a resurgence, with box office hits such as Booksmart, and Bridesmaids, and, in 2019, a stunning debut from writer-director Jason Orley titled Big Time Adolescence. This coming of age story which premiered at Sundance Film Festival to a widely positive reception adds an entrancing new layer to the discussion of friendships on screen.

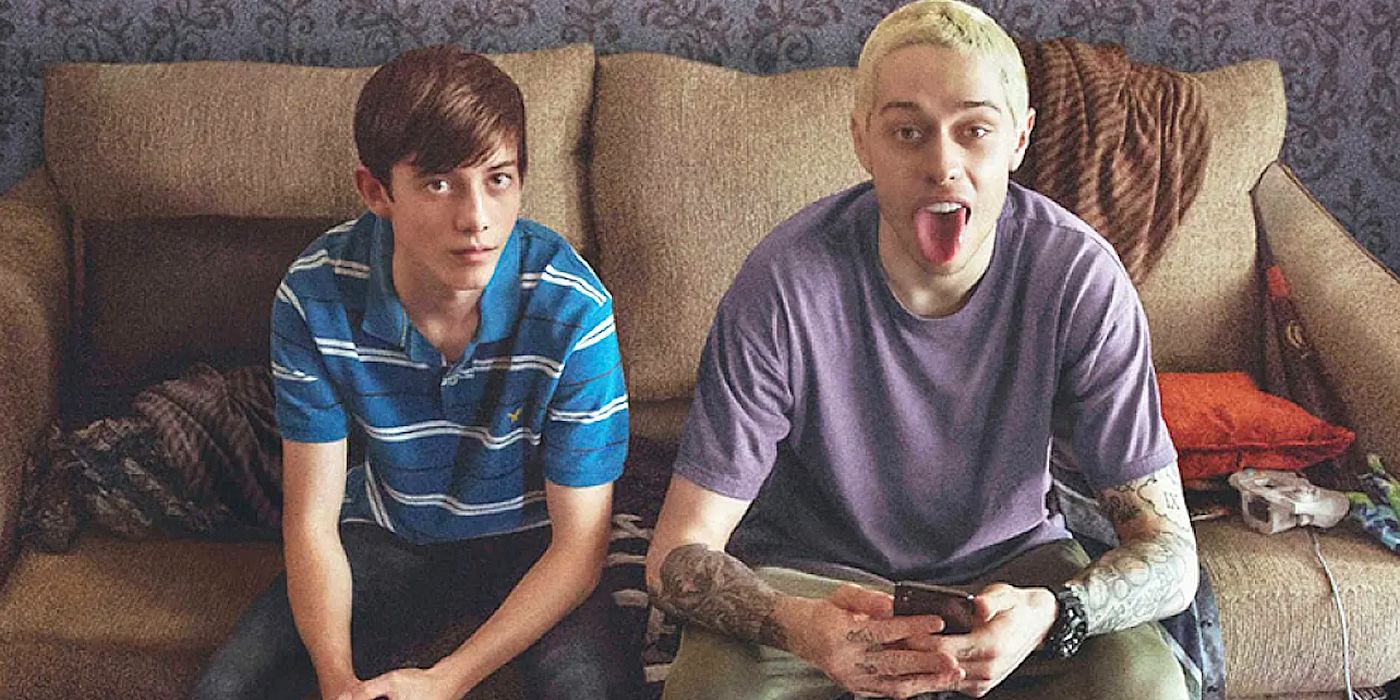

The film follows the journey of the clever but impressionable Mo (Griffin Gluck) as he navigates youth with the unconventional wisdom from his older, self-destructive friend Zeke (Pete Davidson). Throughout the film, Orley gradually reveals the journey of a toxic friendship, which is conversely rooted in love, nostalgia, and a deeply strong bond founded on years of memories and experiences together. By subtly interweaving red flags with moments of affection throughout Zeke and Mo’s relationship, Jason Orley illustrates that friendships, just like romantic love, can hold just the same amount of intense joy and beauty. As Mo makes a difficult decision by the end of the story, however, Orley’s film tells us that friendships can hold the same amount of painful heartbreak, too.

The opening scene to any film is paramount to an audience’s understanding of what is about to unfold before them, and can establish anything from tone to conflict to key character dynamics. The opening of Big Time Adolescence, a flawlessly written sequence that spans over five minutes just before the title credits, does all three. The way Orley both establishes and contrasts Zeke and Mo’s characters indicates that their friendship is not going to be a wholesome or conventional one. The very first frame in the film is Mo sitting in class, looking completely dejected. It’s worth noting Gluck’s performance here, which is spectacular. His expression conveys a mix of dread and regret, but above all, utter exhaustion. Even as police arrive and escort him out of the school, the seemingly indifferent look on his face doesn’t change. As the opening sequence continues, we hear the very first line of the film, “I know this seems bad, but it’s not entirely my fault”. Moreover, the first sounds that are heard in the film are soft, melancholic, almost somber synths and piano chords, composed by Zach Dawes and Nick Sena. Orley and cinematographer Andrew Huebscher also use a dark, muted color palette, infused with serious, gloomy grays and blues. Each of these elements (dialogue, cinematography, performance, and score combined) already sets the film apart from the typical sunny, bright, coming of age story. Orley starts to indicate here that this will not be a film where two people find a beautiful, unexpected friendship. He instead plants the seed for a dark mentorship between Mo and Zeke.

The introduction to Zeke is not a steady shot of him looking regretful like Mo. In fact, it’s him happily stealing vodka from Mo’s parents' cabinet and jumping on the couch with Mo’s sister Kate (Emily Arlook) while Dawes and Sena play a far bouncier, more cheerful music. This stark contrast between the way the two characters are introduced displays their dynamic without even having them interact. Zeke cruises through life without a care in the world, and often at the expense of others. Conversely, Mo has had to pick up the debris of Zeke’s constant destruction. His youth was warped and in some ways stolen because of his older, destructive friend. In a voiceover narration, Mo describes how he felt about Zeke as a kid in the early days of their friendship: “He took me to R-rated movies, he let me taste beer. He showed me a picture of a naked girl on his phone.” The cavalier tone in Mo’s description of Zeke corrupting his innocence amplifies the first key issue within their friendship: Zeke fails to realize that throughout their entire friendship, Mo has always been a child.

Within this same opening sequence, Orley establishes another toxic element that will develop in Zeke and Mo’s friendship. After Zeke and Kate split up, Mo, still young and drawn to Zeke’s charisma, becomes attached to him. When Mo asks to hang out with him, Zeke is reluctant for about a second. He asks Mo, “Don’t you have friends your own age?,” to which Mo responds, “But you’re way cooler.” Zeke is immediately swayed by this and thus, the second complication in their friendship is drawn. Zeke feeds off of the attention he gets from Mo, and Mo feeds off of being treated as an equal by an older, more mature figure in his life. By the time the title sequence hits at minute five, we know exactly what their dynamic is. Although on the surface it seems playful, as the film goes on audiences grow to understand that it’ll be far from harmless.

When protagonists embark on their journeys, often what audiences think of is the start to a heroic climb to success, and despite the clear pitfalls, they succeed and conquer in their journey. In Big Time Adolescence, however, Orley diverts from traditional storytelling in its structure by crafting Mo’s journey as a slow descent into destruction. Because of Zeke’s influence, Mo’s youth becomes entrenched by this toxic friendship with someone who, despite caring about him, doesn’t have his best interest at heart. This is illustrated in the first act turning point, when Stacey, a classmate of Mo’s, asks Mo if he can supply alcohol through Zeke for a party. Upon asking Zeke, he happily agrees with about no hesitation. In addition, Zeke stresses to Mo that he invented the type of party Mo will be going to. He wants to remind Mo that back in the day, he was the man. In this sequence, Orley draws a third toxic element in their friendship while simultaneously paving the way for Mo’s dark journey: Zeke lives vicariously through Mo’s high school glory days, subsequently getting Mo into the same trouble that he did years ago.

However, just when we think Zeke supplying booze for Mo is already a big marker for their dark friendship, Orley takes it a step even further when Zeke propositions Mo to start selling drugs at his parties. At this point in the film, it can be easy to think that Zeke’s motives are just to make extra money. But the subtext seems to go further than that. Zeke wants to use Mo to evade any responsibility. Instead of Zeke selling the drugs himself, he uses Mo as a shield. Mo, still a child, is extremely reluctant. He even mutters under his breath when Zeke is out of earshot, “I seriously hate him sometimes.” Zeke’s new girlfriend Holly (Sydney Sweeney) laughs off the comment and insists that they in fact love each other. In this brief exchange, the complexity of their bond is clearly marked. Despite Mo’s evident frustration and exhaustion by Zeke’s antics, he feels like he needs Zeke to stay socially afloat. However, what’s interesting about Mo’s character is that he’s not just passively being swayed by Zeke. He slowly starts to develop his own unique charm and sense of humor while he sells drugs, clearly enjoying the attention it garners from older classmates. Rightfully so, Orley doesn’t place all the blame on Zeke. They have a complex, symbiotic relationship which, like many toxic friendships, is filled with both affection and frustration.

Mo becomes more and more reluctant about supplying drugs to his friends, but Zeke, charming as he is, convinces him to continue to sell. After years of friendship, Zeke has learned how to take advantage of how impressionable and inexperienced Mo is. Despite this, however, Orley maintains a strong love between them. In one scene, after a fight, they go to a museum together. Zeke and Mo are hot and cold. They love each other and then get mad at each other, but underneath it all there’s a bubbling layer of toxicity. It’s because of this consistent ebb and flow that Mo remains in need of Zeke’s advice. When Mo asks Zeke for help with his crush Sophie (Oona Laurence), Zeke ends up relaying advice to Mo that has destroyed his own relationships. He teaches Mo to make his crush feel insecure and lower her self-esteem in order to make her want him more. This feeds into another complexity in their friendship, which is that Zeke doesn’t learn from his own mistakes, and as a result he passes on advice that he doesn’t realize could destroy Mo. When Mo follows Zeke's tips and ends up losing Sophie's trust altogether, Orley continues to build an empathetic yet flawed character in Zeke. He indicates that Zeke often wants to help Mo, but isn’t conscious of the fact that his guidance is utterly destructive.

As the film races towards the third and most stressful act, it becomes clear that Zeke is incapable of letting go of his toxic behavior. At parties, people begin asking Mo for more drugs, and Zeke starts to supply him with ecstasy. As their business becomes semi-successful, Zeke at one point nonchalantly tells Mo that he quit his job in order to full-time sell drugs with him. When Mo is eventually grounded by his parents, Zeke yells at him, “I quit my fucking job for you.” Moreover, when Mo and Zeke argue about his crush, Zeke tells him, “You wouldn’t even be with this chick if it wasn’t for me”. All of these interactions emphasize one of the most central issues within their relationship, which is that Zeke gaslights Mo and manipulates him to serve his own interest. This cements our understanding as an audience of the intense toxicity that has become part of the fabric of their friendship. By the third act climax of the film, Mo’s drug-dealing scheme gets ratted out by a classmate, and when the police arrive at a party, he jumps out of the window and dives into a pool. Underscored by a beautiful 1960s ballad from Connie Francis, Zeke runs to Mo and rescues him from the police. In one beautiful moment, Orley illustrates the twisted conflict in their relationship: Zeke saves Mo despite the fact that he put Mo in a dangerous situation in the first place. In the classic way of coming of age stories, a protagonist underwater often signals a rebirth. In this case, Mo, dowsed in pool water and looking at Zeke in utter fear that he'll end up like him, has a moment of enlightenment when he starts to realize that their friendship might have to end.

In the final scene of the film, Mo runs into Zeke working at a restaurant months after the police incident. After a brief conversation, Mo sets a boundary with him, despite his clear difficulty in doing so. Mo drives off, leaving Zeke a blurry spot in the background. It’s in this final moment that Orley visually cements this crushing truth of life: some friendships, despite the love and memories, need to remain in the past. What’s so brilliant about Orley and Davidson’s work here is that they don’t pick a side with Zeke. Like any well written, multidimensional character, he’s both flawed and layered. The love for Mo is there, but Zeke cannot escape his old habits that he projects onto his friend. In a reverse coming of age style, Mo has learned not what a friendship is, but rather what it isn’t.