“Ah, how one is starved of Technicolor up there!” sighs an angel in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death as a red flower brings life into the world. In that film, wartime England is rendered in color and heaven in austere monochrome — a reversal of The Wizard of Oz’s trickery. In a decade when most cinema was still black and white, the development of Technicolor promised a vibrant new experience. Two of the most technically brilliant filmmakers of their time (or ever), Powell and Pressburger were early adopters. In 1947 they went full Technicolor in Black Narcissus, a story of repressed desire among nuns that cried out for crimson red.

In Black Narcissus, Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) of the Order of the Sisters of Mary is sent to a remote palace in the Himalayas to set up a monastery. As tensions with the local population and the isolated location take a toll on their mental health, the sisters must face buried memories and forbidden passions – many of which focus on Mr. Dean (David Farrar), an Englishman in the employ of the local ruler. Ultimately, Clodagh faces off against a fellow nun, Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron), who has become dangerously unstable.

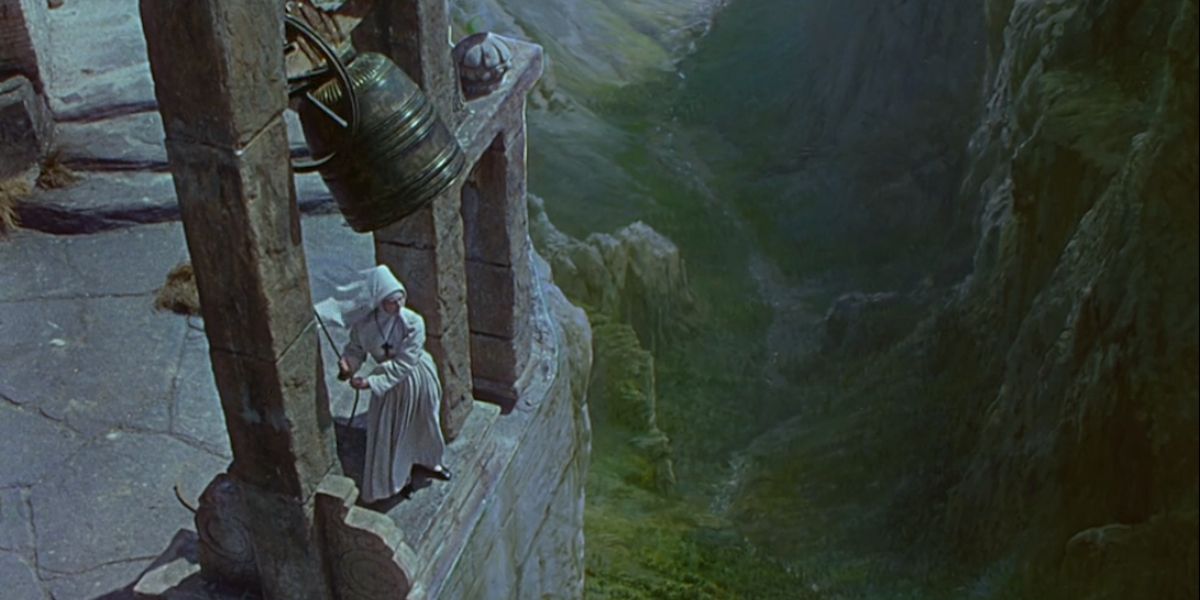

As a film of the 1940s, Black Narcissus feels out of time in many ways, not least because of the Technicolor. Jack Cardiff’s color cinematography is stunning and deservedly won an Oscar (at a time when there was a separate award for black and white). Shot mainly at Pinewood Studios, England, it achieves an illusion of India (albeit a hyper-stylized one) through a mix of incredible sets, models, and matte paintings. Aside from the beautifully detailed and convincing mountain vistas, the film’s greatest composite shot is of the monastery bell. The bell is a relic from the palace’s pre-colonial past, hanging next to a vertiginous, thousand-foot drop – a metaphor for everything in the film that also provides a stunning climax.

The monastery is a character in itself, realized by incredibly detailed and realistic sets. The paintings of orgies and the naked statues (which the nuns significantly cover with white veils that fly away in the unrelenting wind) prefigure the urges that will surface throughout the film. Co-director Powell said that the decision to shoot extensively in the studio was part of the rigorous color control of the piece. The palace, the mountains, and the landscape provide a mix of earth tones, blues, and greens that suggest a natural order.

The sisters, meanwhile, attempt to impose a cool, conformist white on the environment, most significantly through their pristine habits (clothes, that is). Sister Clodagh, the most uptight of the group from the outset, becomes increasingly pallid as the film progresses – a symbol of an unhealthy determination to keep her desires buttoned down. These are the buried memories of the English countryside and her former lover that arise whenever she’s supposed to be praying. She displaces her concern onto Sister Ruth, who is genuinely spending too much time in her room. When Ruth is on the verge of madness, framed in red light against a window, Clodagh sends her a glass of milk that burns with white radiance. Laughing, Ruth pours it away.

Black Narcissus is a far cry from the most famous melodramas of the decade, Brief Encounter and Casablanca. They’re also about thwarted desire, but in those films duty (whether to a marriage or a cause) wins out. While they’re equally passionate, it’s in the mannered style that’s expected of the time, particularly Brief Encounter. Viewed for years as the ultimate expression of British stiff-upper-lip reserve, Noël Coward’s story of an illicit affair now seems an obvious metaphor for homosexuality, an ultimate taboo at the time. The monochrome cinematography of both that film and Casablanca perfectly suits their tone and themes, although Black Narcissus would only be lessened without its Technicolor.

More than just an early experiment with the technique, Technicolor is used by Powell and Pressburger to develop a growing intensity that would have been hard to convey otherwise. The reds that slowly overtake the film say everything that couldn’t be directly expressed in 1947. Of the decade, perhaps only Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious pushes the boundaries of eroticism as far. In that film, Hitchcock subverted the censorship of the Hays Code, which limited kissing to three seconds, by having Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman repeatedly lock lips. There’s no kissing in Black Narcissus, with the filmmakers focussing more on the eyes of characters as they gaze on or fantasize about objects of desire. Those looks say it all.

The film’s ultimate expression of lust comes when Clodagh confronts Ruth, who shockingly appears out of uniform wearing a brilliant red dress and lipstick. In a film laden with metaphor (as it had to be given the time) it leads to the most symbolic scene, as the two women sit across a table from one another – one in white and one in red. Clodagh ostensibly wants to pray for Ruth, who has become sexually obsessed with Mr Dean, although the complicated play between the women is only too clear. Throughout the film they've looked startlingly similar, and now Ruth embodies the unleashed id (to use the Freudian language of the time) that Clodagh secretly craves. Ruth has stolen a gold chain from one of the candleholders and turned it into a necklace. In Clodagh’s surfacing memories, she recalls being given such gifts by her lover.

Dean is the ostensible lust object in the film and Ruth is apparently jealous of the natural attraction between him and Clodagh. However, he’s a reluctant romantic lead and is frequently made to look ridiculous. He sings drunkenly, wears an unflattering hat, and rides around on a pony (a contrast to Clodagh’s memory of horse-riding in England). Dean’s a love-interest by virtue of being the only eligible man on the mountain, but in a moment of candor Clodagh admits that it’s the Young General (Sabu) who reminds her more of her lost love. When Clodagh and Ruth sit down together, the surface tension might be about Dean, but he’s a lackluster proposition. Their silent confrontation is more about one another and their potential.

Inevitably, it comes down to a physical confrontation between white and red, as a rejected Ruth fights Clodagh at the bell. The death drop for one of the characters would play out again in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, another Technicolor lust story that directly references Black Narcissus. Powell and Pressburger would take color even further in the service of story in their masterpiece, The Red Shoes. Powell would use it towards more Hitchcockian thrills in his gloriously tacky solo-effort, Peeping Tom. Meanwhile, Kathleen Byron’s dangerously empowered woman in red would echo through color film, not least in Carrie and Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

As a footnote, it’s impossible to view Black Narcissus from a modern perspective and not pay attention to its more problematic use of color. While most of the extras in the film are native Indians (sourced locally from England’s immigrant population) and the Young General is played by Sabu, the key roles of Kanchi (Jean Simmons) and Angu Ayah (May Hallet) are portrayed by white actors in brownface. It’s indicative of the period in which the film was made, as is the stereotypical portrayal of the incidental Indian characters. The film is implicitly critical of the rigid structure the nuns try to impose on the landscape, but it’s not an attack on colonial rule by any stretch of the imagination. India achieved independence shortly after the film’s release, but Black Narcissus is about the personal turmoil of its characters, rather than the cultural reckoning in store for Britain in the wake of empire.

The detractors of Black Narcissus in 1947 were concerned about its sexual suggestiveness, not its representations. Most notable was the Catholic Legion of Decency, quoted in The New York Times as condemning the film’s depiction of the religious order as “an escape for the abnormal, the neurotic and the frustrated.” They objected most strongly to the depiction of the inner lives of the nuns, demanding that Sister Clodagh’s flashbacks to her time in England were removed in for the American release. Given the later scenes with Sister Ruth, that piece of censorship suggests the Legion really didn’t get where the action was happening. Ultimately, wherever the viewer stands on nuns and their habits, Black Narcissus remains a technical marvel and a foretaste of a single color that would dominate cinema as a signifier for passion – red.