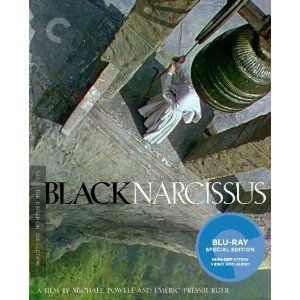

The Brits are best known for Merchant/Ivory-type films – adaptations of classic novels, Shakespeare, class. This is ironic for a number of reasons, perhaps most notably because neither Merchant nor Ivory are British. Though it might be fair to say that a number of the great British directors weren’t sensualists, but even there if you watch the films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, there is great passion, and great sensuality. Powell and Pressburger’s Black Narcissus practically drips with under the surface eroticism. Deborah Kerr stars as a nun sent to the Himalayas to start a school, but once there she fights against the environment to stay in control of her fellow nuns and herself. My review of Criterion’s Blu-ray of Black Narcissus after the jump.

When a rich general gives a large temple in the Himalayas to an English nunnery, five nuns are sent to colonize it and assist the locals. Sister Clodah (Deborah Kerr) is put in charge of the new convent, and though she thinks she's up to the task, she is viewed as too young and too arrogant for the assignment. Most of the nuns sent with her are meant to be helpful, but Sister Clodah is also given the difficult Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron), who acts and feels out of place in the nunnery. As the nuns move in, they are helped by a cynical, attractive white man Mr. Dean (David Farrah), who thinks that the women will not be able to adapt to a strange, new culture. He should know — he's seen the palace go through many hands, and perhaps because the temple used to be the home of the old rajah's kept women, something about the location makes it hard for people to remain dedicated to their passions while staying there.

Mr. Dean acts as an advisor for the nuns, and though they need his help, he frustrates them by not keeping his passions in check. Adding to the sexually charged atmosphere, the nuns are given a young girl to watch over (Jean Simmons), who is seventeen, of marrying age, and desperately looking for a husband. There's also a local prince (Sabu) who has come to receive an education, but unfortunately is an eligible bachelor — stylish and intriguing and wearing Black Narcissus, cologne from England. As the film progresses, the tension in the nunnery grows. Sisters Ruth and Clodah find themselves drawn to Mr. Dean, though Clodah can't admit it; Ruth is easily provoked and soon troublesome; one of the nuns plants flowers instead of food; and as the seasons change, Clodah is drawn to reflecting on her previous life, which makes it harder for her to behave like a nun, especially around the attractive Mr. Dean.

Using any religious group as a film's subject-matter has to be done carefully, as it is easy to fall into the trap of bad metaphorical content — among other obvious pitfalls. What Powell and Pressburger do in Black Narcissus is invest in the characters, and then illustrate their spiritual decay. Jack Cardiff won an Oscar for his color cinematography, and his luscious three-strip Technicolor imagery well deserved the award. But equally, it's Powell's use of the colorful Himalayas to imply the inner passions of the nuns that makes the photography so excellent — a brilliant creative choice, and the film smolders because of it. As the nuns slowly reveal their pent-up frustrations, Powell masterfully guides us through their desires, so that when the film reaches its harrowing climax, it never feels forced, although it is shocking and effective just the same. Black Narcissus even has a tenuous relationship with horror films — hard to believe, but there are shots of an insane-looking Ruth that must have been inspired by Val Lewton, and influential on both Herk Harvey and George Romero (the latter a huge Powell-Pressburger fan). She's practically a zombie. This is all the more impressive because the entire movie (save a handful of shots) was done on soundstages.

Also well-handled in Black Narcissus is the underlying subtext about British colonization — a potent subject, especially post-World War II. The British nuns arrive in this foreign land to change their new environment, but the film shows us that these characters are more affected by their surroundings, rather than having any effect upon them. Instructed from their arrival never to take serious medical cases from the villagers, from the beginning they are impotent; if they fail, they will be rejected out of superstition. And when they ignore their instructions (to help a dying baby), they are finally ostracized. Trying to control an unfamiliar environment provokes their own problems — being unable to adapt to their setting keeps them prisoner to failure.

The film is presented in its original academy ratio (1.33:1) and in a 2.0 monaural soundtrack. The film went through a recent restoration, and as such it looks much better than their previous versions, though not as excellent as their recent Red Shoes restoration. As a three-strip Technicolor film, restoration can be tricky business, and though there’s some minor shifting of colors, it’s kept to a minimum, while the images appear more vibrant than ever. Black Narcissus was one of Criterion's first Laserdiscs — released with analog audio, it had no extras other than an audio commentary with Martin Scorsese and Michael Powell. This track has been preserved for the new Blu-ray, and it is marvelous to listen to, as Scorsese - though muted - is obviously enthusiastic about the film. Powell was near the end of his life (he died in 1990) when the track was recorded, but he has some solid observations about the shoot. Carried over from the first DVD release is a 27-minute documentary on Jack Cardiff's cinematography on the film, which features interviews with Cardiff, Kathleen Byron (who still looks beautiful), Scorsese, and Ian Christie, among others. The feature is an excerpt of a longer career-profile documentary on Cardiff, but it includes some nice bits of information on the film, and on the Technicolor process as well. Also from the first release is a theatrical trailer. Not included are the production stills, and photos of deleted scenes. But now there is a Bertrand Tavernier video essay on the film (9 min.), and another Tavernier piece (17 min.) about the film and his relationship with director Michael Powell. Also included is a profile on the making of the movie with interviews with Byron and Cardiff (25 min.).