Is Deckard (Harrison Ford) a replicant or is he human in Blade Runner? It’s one of the most enduring questions in science fiction, and despite it being over forty years since the release of Blade Runner, there’s no indication that an answer is coming our way. There’s ample evidence for both sides, and even if the ending does lead the viewer down one road over the other (assuming you’re watching The Final Cut, that is), there’s enough ambiguity to keep both possibilities open. Combatants in the debate are some of the most passionate minds on the internet, and at this point the war seems destined to still be a contentious issue long after this futuristic depiction of 2019 Los Angeles starts to resemble a period piece. Even people involved in the film don’t know what to make of it, with the conflicting responses they’ve offered only complicating matters further. Ridley Scott says he’s a replicant, Harrison Ford says he isn’t, and countless others don’t know where to begin, but there is one controversial answer that doesn't come up as frequently: the answer doesn’t matter.

Now, it’s important not to misconstrue this as meaning that the original question is a waste of time. As with most aspects of Blade Runner, there’s too much thematic depth at play to allow for such easy summarization, but it does capture the essence of this topic better than any other response. The answer doesn’t matter because the question is pointless – the answer doesn’t matter because the question is the point. Throwing Deckard’s identity into doubt is the stroke of genius that elevates Blade Runner from brilliant to masterful, and trying to provide a solution sabotages that which makes it so effective. Screenwriter Hampton Fancher would go on to say in an interview with the Los Angeles Times for Blade Runner 2049 (where he reprised his role as writer) that “Deeming Deckard a replicant closes the door on the party… it’s got to be up in the air or there’s no dog fight." He follows this up by adding (somewhat ominously) that “life is ambiguous” – a quote that perfectly encapsulates this complicated debate.

'Blade Runner' Thrives on Mystery

But first, let’s take a step back from Deckard and concentrate on the dystopian version of the future we find him in. The world of Blade Runner is one that revels in paranoia. Anyone who’s anyone had long since abandoned Earth for the relative sanctuary of the off-world colonies, and those unfortunate enough to have been left behind are forced to contend with a planet ravaged by ecological destruction, brought about by a hyper-globalized version of capitalism that has seen corporations casting their oppressive net over every facet of society. Watching Blade Runner is like watching the final days of a dying planet with no hope of a final reprieve, and given that even the animals are now just electric copies of their former organic selves, it’s hard to imagine such a scenario leading to anything other than a civilization drenched in uncertainty.

Given humanity’s desire to always find something to blame their problems on, it’s no surprise that the last remaining citizens of Earth would direct their anger towards the one marginalized group that still exists – replicants. Despite being physically and biologically indistinguishable from humans, they still carry the moniker of being "different," and that’s all the excuse people need to justify hating their artificial counterparts who exist only as slave labor. Before long, derogatory terms like “skin-job” become common parlance, but eventually a bloody off-world rebellion causes replicants to become illegal on Earth, necessitating the creation of the titular blade runners to “retire” any that still exist (a fancy way of disguising the word “murder”). By 2019, the threat (real or not) posed by the replicants looms large over society, creating a land of confusion that is steadily building the foundations of its own demise.

'Blade Runner' Doesn't Suggest Deckard Isn't Human In His First Appearance...

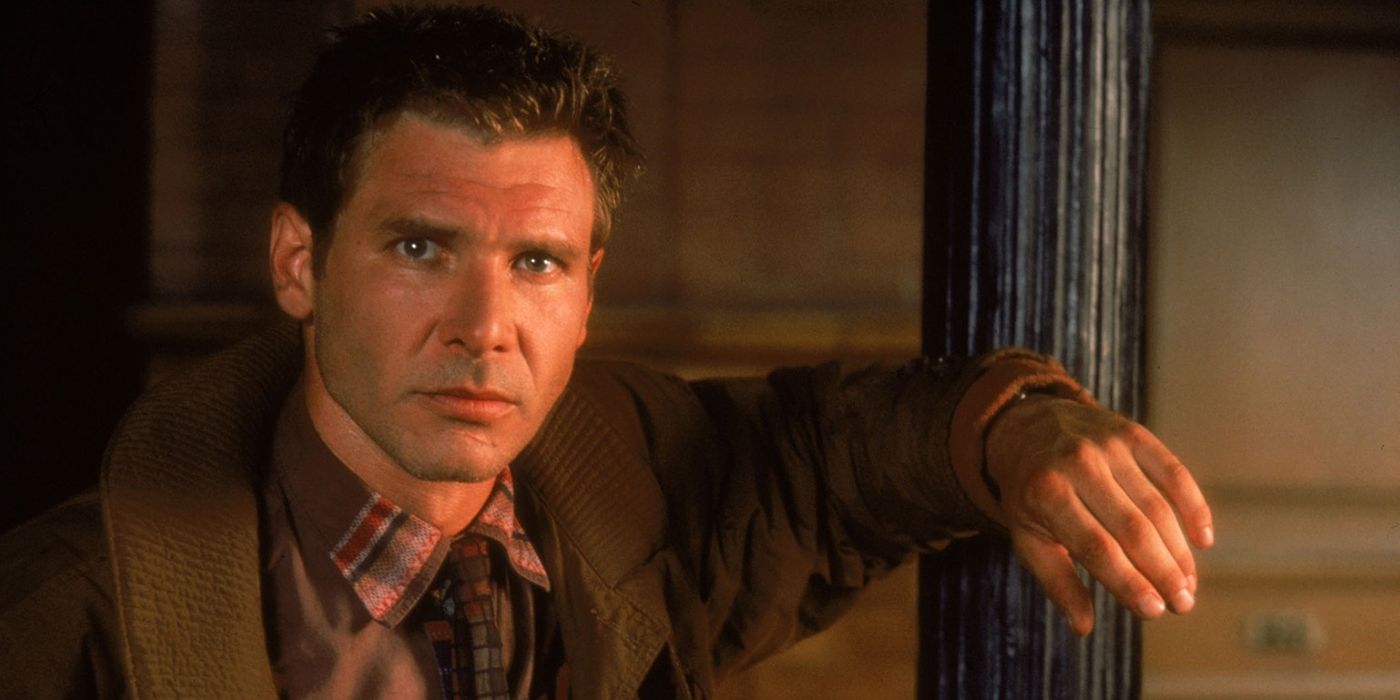

It’s amidst this turmoil that we’re introduced to Rick Deckard, a retired bounty hunter called back into service by the LAPD after four replicants – led by the enigmatic Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) – escape from their off-world imprisonment in search of their creator, Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel), in the hopes that he can extend their four-year lifespan. Looking at Deckard, you’d be forgiven for thinking he was a man lost in time. His gruff, self-loathing lifestyle that sees him casually ignoring the rulebook at the drop of a hat – all the while having to grapple with the mysterious femme fatale Rachael (Sean Young) – gives him the appearance of a classic noir detective who’s been left behind by a changing world, and now has become as much of an enigma as the cases he used to solve. Let’s put a bookmark on that thought.

Regardless of how cliché he may first appear, Blade Runner wastes no time establishing his verdict on the biggest issue of the day. “Replicants are like any other machine,” he tells Tyrell during their meeting. “They're either a benefit or a hazard. If they're a benefit, it's not my problem.” It’s a rather dismissive way of viewing his future targets, and it could almost be interpreted as him trying to rationalize his own heinous actions if he didn’t believe it so staunchly. But this is only the first of many instances where he makes his opinions on replicants known. From the way he treats Rachael like his personal property, to the way he “retires” his targets with no remorse despite them just searching for a way to extend their life, it’s clear that Deckard subscribes to the theory of replicants being second-class citizens. No wonder he was picked for this mission.

And yet, despite the nature of his job continually confronting him with the truth of how identical humans and replicants are (to the point that some, like Rachael, don’t even realize they’re not human), Deckard himself displays no concerns regarding his identity. He knows exactly what he is, and the notion that he could be anything else is absurd. Blade Runner never confirms that he’s human, but the way characters speak about his previous assignments or the abundance of photographs in his apartment certainly indicates him as someone with a far-reaching history. In addition, Hollywood films tend to put an audience surrogate at the forefront of such fantastical stories to aid the audience in relating to what’s happening onscreen (a notion Ford has repeated when referencing this very film), further implying that Deckard is human.

...Until 'Blade Runner's Final Scene Makes Us Question Everything

And then the final scene happens. With the four replicants dead, Deckard returns to his apartment to collect Rachael, but just as they’re about to escape Los Angeles, he finds a small origami unicorn left by Officer Gaff (Edward James Olmos). Earlier in the film, Deckard had daydreamed about a unicorn while drunkenly slouched over a piano, but there’s no indication that he has ever told anyone about these dreams. The implication is that Gaff knows Deckard’s most private thoughts, and given that it has already been established that the Tyrell Corporation implants false memories into replicants to make controlling them easier, who’s to say that Deckard hasn’t been hunting his own kind the whole time?

Ridley Scott has confirmed that this was his intention with the scene, and while there are other hints towards Deckard being a replicant – he never provides Rachael an answer when she asks if he’s taken the Voight-Kampff test himself, and during one scene his eyes appear to glow (although this could have been a lighting mistake) – the unicorn is easily the biggest clue. It’s amazing that such a simple inclusion could alter our entire perception of everything we’ve just watched, and crucially, Blade Runner never elaborates on it. Instead Deckard just silently walks away until the closing of an elevator door smashes us to the credits, leaving the viewer to ruminate on the implications of the ending themselves. If we’re taking Scott’s view of the scene as gospel (and given that he’s the director, that wouldn’t be too outrageous), then the ending is pretty clear-cut, but since when has critical analysis extended only to how the original author interpreted their work?

'Blade Runner's Ambiguity Is What Makes the Question So Impactful

At its core, Blade Runner is a film about personhood – what it means to be a human and whether we can extend this definition to other beings. A replicant may be designed, not born, but that doesn’t stop it from conveying the basic desires of a human with such pinpoint accuracy that only a machine can tell the difference. It can be argued that these desires are constructed rather than something it creates naturally, but if the emotions being generated feel just as genuine as the real thing then does the discrepancy even matter? Besides, we’re continually told that replicants lack empathy (one of the essential ingredients of humanity), despite the ones Deckard encounters displaying the most warmth and compassion in the whole film. Deckard himself spends most of the runtime as a cold and heartless individual, only shedding this frigid exterior after falling in love with Rachael, a character who is explicitly confirmed to be a replicant. Tyrell describes his creations as “more human than human," but as it turns out, he was closer to the mark than he realized.

The origami unicorn is not supposed to be a last-minute trick, but the moment that encompasses the themes we’ve spent the past two hours contemplating. Up until then, most viewers will have happily believed that Deckard was human without considering that he could be anything else. And then, just when you think you’re done, a seed of doubt is planted in your mind. Some will dismiss it, others will let it grow into a forest… the reaction itself is irrelevant. What’s important is that initial moment of doubt – that moment when the line between humans and replicants becomes utterly blurred, and you find yourself wondering if the man before you really is what he says he is. We’ve already seen evidence that memories and photographs – once sacred objects that tethered us to our past – are now just another tool for corporations to weaponize against us, and their effectiveness in making Rachael believe she was human has already been demonstrated. If they’ve done it once, why can’t they do it again? And if Deckard is wrong about his identity, then how can we be sure what anyone is?

We don’t know, and that’s the beauty of it. Blade Runner raises a lot of questions without providing many answers, and it’s because of this atmosphere of ambiguity that the film has retained its lasting influence on the sci-fi genre. Its exploration of the human condition in a world where technology has birthed a new form of life is endlessly fascinating and increasingly relevant, and whether or not people’s opinions on Deckard change following the film’s conclusion says a lot about where they stand on this contentious debate. Providing a definitive answer undermines the openness that makes Blade Runner so enticing, and while there’s no denying that Ridley Scott played a crucial role in making Blade Runner the masterwork that it is, his commitment to making his interpretation the only interpretation brings to mind his decision to direct two Alien prequels while failing to understand what made the original work. Most things in life are a mystery, but as long as you’re still happy, why should that be an issue? The last time we see Deckard he doesn’t seem too concerned by the origami unicorn. He knows what he is, and that’s what matters.