It's hard to overstate the cultural impact that Blade Runner has had on cinematic history. Directed by Ridley Scott and written by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples, the iconic film — a gritty recipe of sci-fi, neo-noir, and romance — was based on Philip K. Dick's 1968 dystopian science fiction novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Given its status today as one of the crowning jewels of sci-fi cinema, it's easy to forget that the film was a colossal box office failure upon its theatrical release in 1982, with critics and fans alike citing slow pacing, lack of action, and Harrison Ford's now infamous voiceover narration — a controversial Warner Bros. decision, much to Scott and Ford's disdain — as two major reasons for the flop. It also didn't help that the summer of '82 was an embarrassment of riches for sci-fi fans, with powerhouses like Tron, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, and of course, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial coming out within the same two-month span. Even John Carpenter's goopy masterpiece The Thing, which coincidentally was released in theaters on the exact same day as Blade Runner, utterly bombed with critics and audiences alike.

That being said, the reviews for Blade Runner were much more favorable upon the film's re-release in 1992. In this version, dubbed the "Director's Cut," Scott scrapped Ford's stilted voiceovers and inserted a 12-second scene that made for a much more ambiguous conclusion. There are in fact seven versions of the film known to exist, so it's not difficult to understand why Scott has gone on to say that Blade Runner is by far his most personal film. Only five versions have been released, with the latest being the 2007 25th Anniversary "Final Cut" version, edited by Scott personally. Now, we could debate for hours about which version is best, but for the sake of this review, we are taking a look back at The Final Cut.

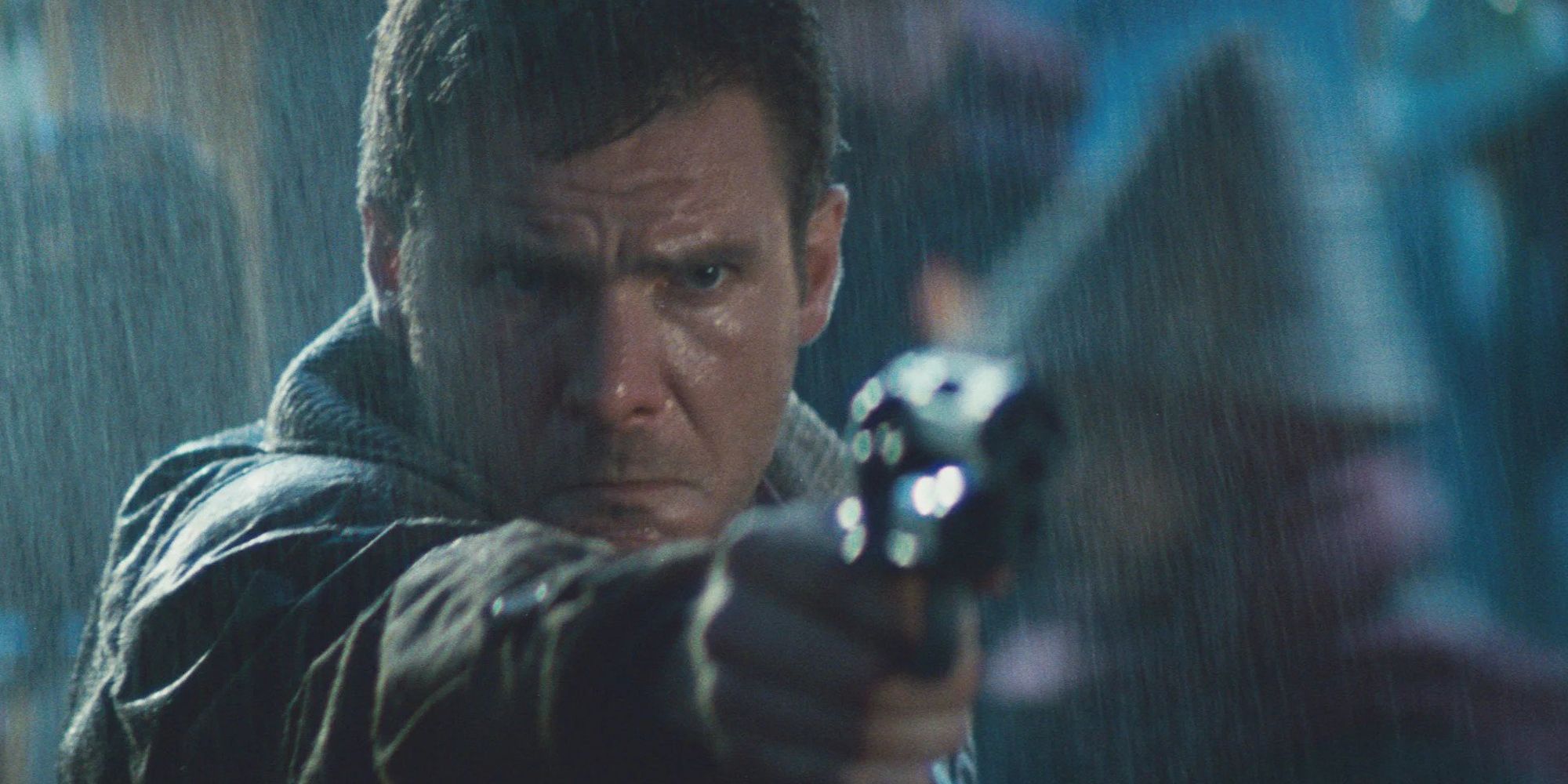

Blade Runner takes place in the rainy tapestry of dystopian gloom that is Los Angeles in the future of 2019. Harrison Ford plays burned-out LAPD detective Rick Deckard, who is tasked with hunting down and killing four fugitive "replicants" who have returned to Earth illegally from off-worlds. Replicants, bioengineered humans created by the powerful Tyrell Corporation, are gifted with superior strength, speed, agility, resilience and intelligence. The fugitive group of replicants are products of the "Nexus-6" (the supreme replicant) upgrade, and are revolting against their pre-programmed four-year life span. With Deckard hot on their heels, the leader of the replicant fugitives, Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), is on the hunt for their maker, CEO Eldon Tyrell (played by the fantastic Joe Turkel, who sadly passed away earlier this summer) to negotiate their life span.

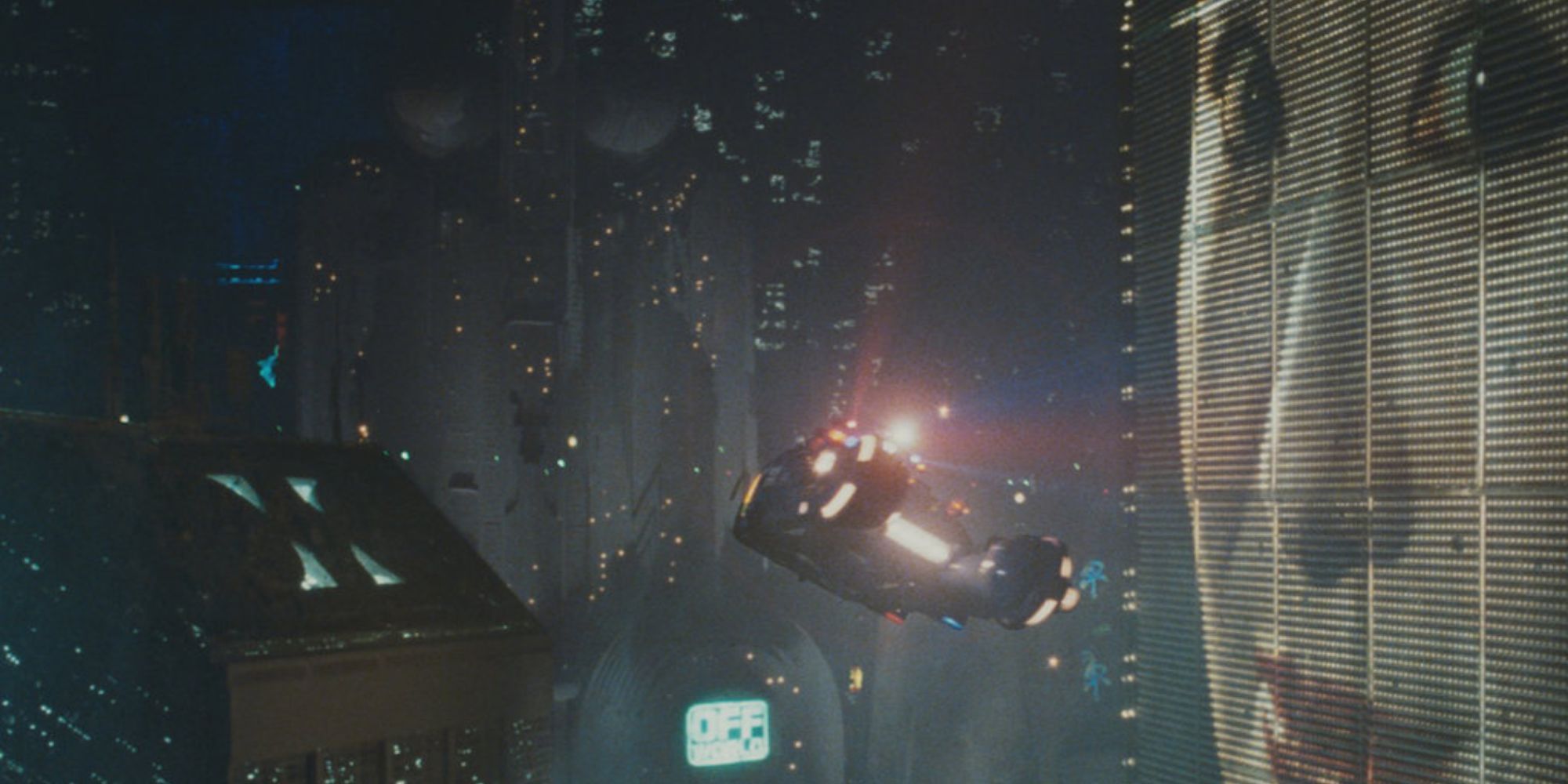

Ford, never one to shy away from voicing his curmudgeonly displeasure, hasn't historically had the most glowing things to say about Blade Runner. He told the Boston Globe in 1991, "I played a detective who did no detecting. There was nothing for me to do but stand around and give some focus to Ridley's sets." While it's safe to say that many would disagree, Ford was not wrong about one thing: the visuals of Blade Runner are the star of the show here, even 40 years later. Scott's futuristic Los Angeles is drenched in dystopian gloom. The skyscrapers may be towering, and the cars may fly, but as technology soars, social order crumbles. The overcrowded city is grimy and streaked with constant rain, the streets reflect the neon glow of massive billboard advertisements. Visually, Blade Runner is a dystopian dream.

The critique from audiences of the original theatrical release about the film's slow pacing is not entirely inaccurate. Blade Runner's pacing is indeed slower than your usual major blockbuster and there are noticeably long lapses between the action. However, this is where the futuristic landscape shines. It's not hard to see the visual influence that the film has had on the genre. Bursting with cyberpunk aesthetics, you can see Blade Runner's fingerprints all over films like The Matrix, The Fifth Element, and Ghost in the Shell. Scott's set is an appropriate visual backdrop for a film that so intricately ties together the dark, corrupt world of neo-noir with the social decay of dystopian science fiction.

Thematically, Blade Runner ruminates on the question of what makes us human. And there's no better moment in the film that captures this fundamental question than the final showdown between Deckard and Batty. After unexpectedly saving Deckard from plummeting to his death, Batty delivers his now iconic death soliloquy, often referred to as the "Tears in Rain" monologue. In Batty's last lines before his death (penned by Hauer himself), he says, "All those moments will be lost in time... like tears in rain." Hauer is magnificent in the film, but particularly here in Batty's final, deeply poignant moment, his parting words a reminder to Deckard that human or not, replicants love, lose, and die just like everyone else. Their lives — all four short years of it —are rich with experiences, some actualized and some implanted, which will be lost in time when they fade away.

Hauer's performance as Batty is poetic, a welcome respite from admittedly, the more one-dimensional traditional masculinity of Ford's Rick Deckard. This is not meant as a dig against Ford, but rather, a reaffirmation that the masculine "hard-boiled" detective/action hero archetype always leaves much to be desired (and yes, I know, Deckard may or may not be a replicant, and yes, that does make him more interesting. But for all intents and purposes Deckard fits the traditional masculine hero stereotype, and no, it isn't that interesting.)

And on that note, I do have to pull out the "this didn't age well" card for a brief moment. Blade Runner is a visual feast even four decades later, but if there's one moment the film does not transcend time, it's the sex scene between Deckard and Rachael (Sean Young). Before sending Deckard off on his mission, Tyrell introduces him to smoldering, but tragic femme fatale figure Rachael, a replicant who doesn't know she is a replicant due to implanted false memories. The two strike up a romance, in which Deckard, presumably, realizes that Rachael is not simply an android, but the woman he loves. Deckard and Rachael share an ambiguously consensual sex scene that most certainly is meant to be seen as romantic, per the cheesy saxophone crooning away in the background of the scene. In reality, the moment is anything but. In said scene, Deckard kisses Rachael, who promptly flees the room. He follows her, then slams the door and forcefully pushes her against the wall, preventing her from leaving. Then, he commands her to tell him to kiss her. A scene that perhaps was meant to convey passion conveys quite the opposite.

Yes, there will be a chorus of readers who will argue not to bring my 21st century feminism in to the sacred realm of classic cinema, and to these readers I say this: Blade Runner is a film about being a human. Being a woman — specifically a woman who is struggling to understand and assert her own humanity after making the horrific discovery that she is in fact, inhuman — is relevant to the conversation.

Now, this scene could be interpreted in a few ways, but what it really boils down to is intent. At the heart of Blade Runner is the question of whether or not replicants are machines or living beings. Some have argued that the purpose of this scene is to make us ask the morally gray questions: do replicants have agency? And furthermore, are replicants capable of love? However, with the whole smoky noir romanticism of the scene, what is more likely is that this scene is simply indicative of the '70s-'80s sexual norms, romanticizing the aggressive male conqueror who has "won over" an unwilling woman.

But, I digress.

Taken as a whole, Blade Runner easily stands the test of time as a pioneer for the science fiction genre. With its sweeping visuals and philosophical underpinnings, this cult classic relies not on fast-paced action, but an all-encompassing atmosphere and mood, to tell a complex story about humanity. Blade Runner gets to the heart of a timeless question: what makes us human? And furthermore, what makes our lives — our feelings, our relationships, our experiences — more valuable than others? Blade Runner is timeless, yes, but looking at these questions, Ridley Scott's sci-fi masterpiece is more relevant than ever before.

Rating: A