From the politicized depression-era dramas of the 1930s to the nuanced voyeurism of films noir in the 1940s and 1950s, the history of American cinema is built upon a foundation of overt and covert ways of seeing, as the silver screen often served as a looking glass for reflecting and defining sociocultural anxieties. Following in a long tradition of Hitchcockian ruminations on the dangers of observation, both Brian De Palma’s Reagan-era meta-thriller Blow Out and Kathryn Bigelow’s Y2K science-fiction satire Strange Days cut to the core of late-twentieth-century anxieties of political conspiracy and digital paranoia through their critical visualizations of memory invasion.

While Blow Out taps into a sound-based investigation of the central characters’ lived experience of a possible political assassination, Strange Days continues the previous film’s subversive tradition through the virtual reality-based reliving of salacious scenarios and traumatic events, eventually revealing the role of police corruption in the death of a famous rapper. Although the two films stand apart as equally fascinating and foundational artistic statements in their respective director’s filmographies, their similar invocation of Hitchcockian intrigue à la Rear Window within unique genre frameworks of political mystery and science-fiction unify the films as a cinematic bridge between the disillusioned patriotism of Reaganite optimism and the convoluted communication of the early digital age, presaging the prominence of surveillance in the twenty-first century.

Although De Palma locates Blow Out comfortably within the framework of Reagan-era nationalism and the ensuing American insularity, it is essential to acknowledge the integral role that Nixonian disillusionment and the subsequent cinematic thrillers of the 1970s played in formulating the subtext for De Palma’s masterpiece. In the wake of Watergate and the atrocities of the Vietnam War, the New Hollywood leaned into a renewed manifestation of genre filmmaking that mirrored the political paranoia and personal discontents of the era.

Releasing revisionist thrillers that bordered on nihilistic like Alan J. Pakula’s conspiracy-centric stylized statement The Parallax View and Sydney Pollack’s annihilative mystery Three Days of the Condor to incredible acclaim and box office success, the cinematic landscape of the 1970s tapped into the disturbingly relevant well of national distrust and political turmoil to draw in audiences by empathizing with their existential fears. Perhaps more elegantly and precisely than its predecessors, Blow Out equally politicizes and personalizes both the fear of being watched and the anxiety of seeing something dangerous, incriminating, and potentially life-threatening.

Opening with a “movie-within-a-movie” sequence of the b-level horror film Co-Ed Friendly, De Palma immediately establishes the poetic paranoia that pervades the film by placing the audience into the first-person perspective of the sorority serial killer villain, indicting the audience of their own cinematic “surveillance as entertainment.” Although the point-of-view cinematography from the perspective of a serial killer stalking girls in and around a sorority house foreshadows the eventual government-backed, cover-up “serial killings” by Burke (John Lithgow) in the film’s second half, the opening sequence also builds an atmosphere of dread and doubt that functions as a critique of Reagan era optimism through a tragically honest approach to political corruption and lurid criminality throughout the film.

When Jack (John Travolta) is tasked to search for new wind for the fictional film’s atmosphere and a new scream to add to the Psycho-like shower murder in the film’s first, the first-person voyeurism that the cinematography evokes also becomes an auditory construct, as John Travolta’s protagonist invites us into his sonic perspective through his recording of nature sounds and accidental capturing of audio from a car crash.

In a manner similar to the accidentally photographed murder at the center of Michelangelo Antonioni’s groundbreaking arthouse film Blow Up, Blow Out sees Jack unravel at the seams as he attempts to uncover and bring to justice the assassination of Pennsylvania Governor George McRyan through his audio recording. Echoing the first-person perspective of the “film-within-a-film” opening, a sequence at the center of the film sees the audience take on the audiovisual point-of-view of Jack as he relives the moment of recording the potential assassination, aligning the audience within the protagonist’s multi-sensory perspective as he grapples with the government conspiracy in which he is caught.

While it is entirely possible to call Jack’s unintentional surveillance of the tragedy a positive example of seeing the truth in the midst of a dishonest political yarn, the psychic and bodily fallout of the recording suggests that his accidental anti-government observation is an impossible task in the midst of the corrupt behemoth of Reaganite American politics. The film’s final sequence at the firework-laden “Liberty Festival” sees the personal and political consequences come to the forefront, as Jack witnesses and records the murder of Sally (Nancy Allen), the former governor’s escort whom he liberated from the sunken car in the film’s inciting incident, by the government-hired assassin Burke.

By juxtaposing the death of Sally against the backdrop of a joyous patriotic celebration, De Palma finalizes the critique of the American political establishment as an ironic and corrupt force of destruction that wears a mask of individual freedom and nationalistic optimism. The haunting final moments see Jack forced to surrender to his own exploitation and personal paranoia as he offers Sally’s final scream as the sound effect for the film from the reflexive introduction, emphasizing a devastating poetic continuation of surveillance and conspiracy through the cinematic form.

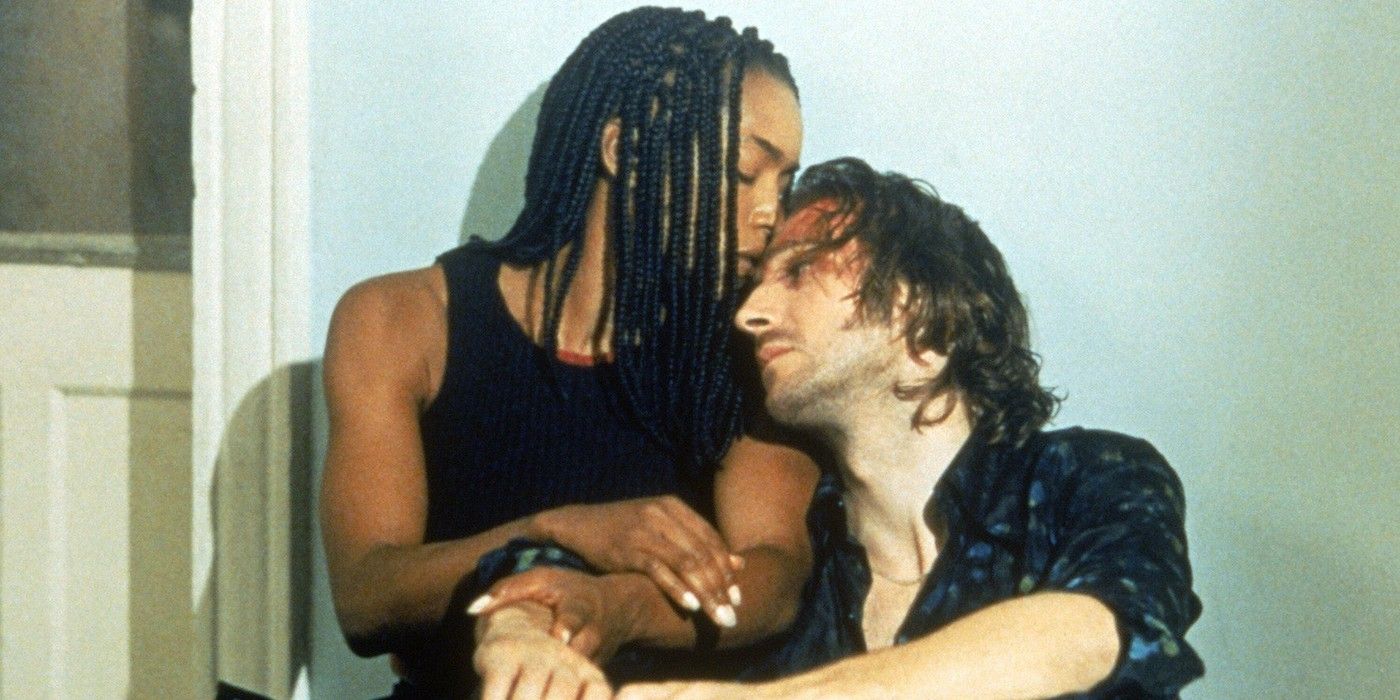

Building on the foundation of Blow Out’s approach to voyeurism and political intrigue, Kathryn Bigelow’s underrated and unfortunately difficult-to-find Strange Days extends the structures of surveillance into the realm of human memory, as the film’s policeman-turned-illegal memory dealer protagonist Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes) is forced to confront the ethical fallout of his VR-style memory archive. In a manner similar to Blow Out’s meta-cinematic opening, the introductory sequence of Strange Days showcases the first-person perspective of a restaurant robbery as recorded on the memory-sharing device. While the scene ends in the tragic death of the memory’s “protagonist,” the camera cuts from the point-of-view memory to Lenny’s shocked removal of the memory-viewing apparatus.

Immediately upon Lenny’s rejection of the content in the memory as particularly exploitative and unnecessarily violent, Strange Days establishes the moral compass of the alternative 1990s world in which the characters find themselves. Although the film goes on to visualize first-person memories of various acts of lurid sexuality and extreme violence, Bigelow’s use of the first-person nuances the narrative information to critique the increasing desensitization of the public through the 24-hour news cycle and the early internet, connecting fears of surveillance directly to the rise of the digital sphere four years before The Matrix.

Although Bigelow’s revisionist manifestation of first-person filmmaking probes more directly into the space of memory rather than the locus of personal observation, the climactic “memory clip” discovery of the murder of fictional rapper Jeriko One by the LAPD fuses the psychological bent at the center of the film’s understanding of surveillance with a post-Rodney King critique of American police corruption. While the film’s finale features an end-of-the-century celebration similar to the Liberty Festival in Blow Out, Bigelow’s conclusions are far more hopeful, as Lenny’s public revelation of the Jeriko One tape leads to the murderous police officers being brought to justice.

Perhaps the anxious optimism at the center of Strange Days positive surveillance-based conclusion may be attributed to the newness of internet connectivity and the hopefulness of digital innovation; however, Bigelow never compromises on imbuing the film with her signature skeptical tone, which helps maintain the film’s particularly relevancy concerning racial justice and widespread corruption in policing. By prioritizing memory as the ultimate manifestation of truthful sight, Strange Days looks toward the future as a possible yet complicated horizon for liberation from conspiracy and political manipulation.

While many contemporary viewers may dismiss Strange Days as a dated science-fiction exercise, it may be said that the film was made with the knowledge that it would be a time capsule of turn-of-the-century paranoia. Nevertheless, the ideas at the center, particularly the preservation and erasure of memory as well as the convoluted concept of free will in an Orwellian future, are a glorious mid-point between the memory-centric masterpieces of Alain Resnais and the digital age psychological intrigue of contemporary films like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Mindscape. As with all great science-fiction films, Strange Days works because it prioritizes reflecting its own time through a vision of a future and alternate reality rather than attempting to predict the future through speculation and special effects. By elevating the technological artifacts of its mid-90s moment as embodiments of atemporal anxieties, Strange Days leans into the moment of its creation aesthetically and ideologically, establishing the film as a timeless critique of police corruption and the exploitative structures of surveillance.