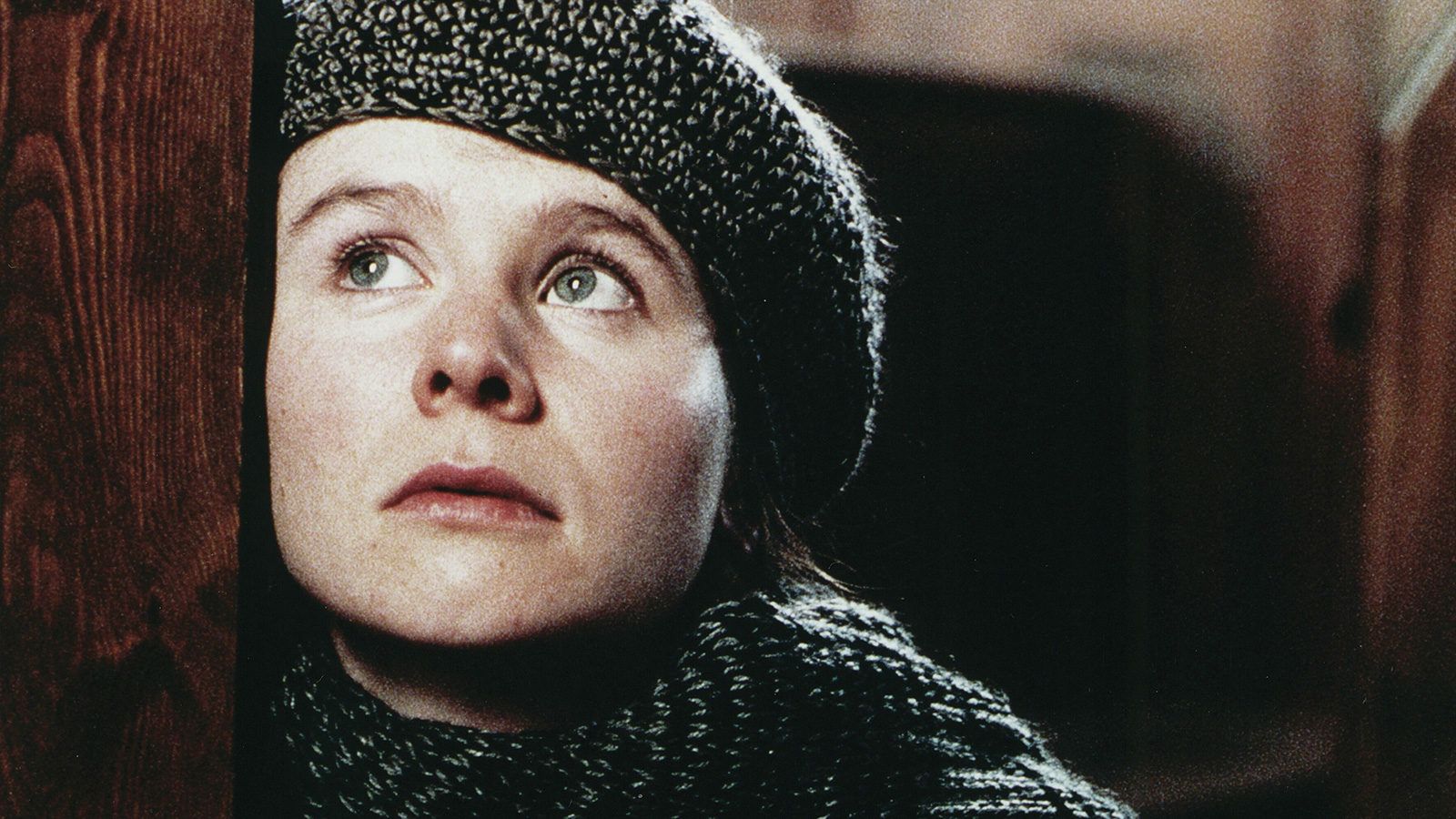

A wide-eyed young woman, battered and bruised, advances on turbulent waves in a small boat. Her destination is a barge, on which some alarming men await her arrival. They stare her down like predatory animals. It’s certain that she’s entering a very dangerous situation, but she glares boldly, directly into the lens of the camera—undaunted, determined. The uninformed might call her naive, but by this climactic scene in Lars von Trier’s classic Breaking the Waves, the viewer is aware that she is a Knight of Faith.

This committed, peculiar character is Bess McNeill, brought to life in a passionate performance by Emily Watson. Watson and von Trier each rose to international prominence with the 1996 release of this film. They did so against all odds, as it's a deeply challenging work. Its formal experimentation, numerous ambiguities, and uncompromising brutality make it a tough experience, but an undeniably powerful one. A religious epic by no means, the film employs a very stripped down, minimal aesthetic to profoundly examine concepts of faith, doubt, love, and God. As such, von Trier’s film manages to approach the divine through the tangible, the spiritual through the natural.

The film is set in a severely repressed and oppressive Calvinist village in early-1970s Scotland. Women aren’t allowed to speak in church here. The opening scene has Bess attempting to gain the approval of stuffy church elders in her intention to marry an outsider. It’s made immediately clear that these bearded old men care less about any sincere spirituality than they do crass judgement and empty ritual. Their church doesn’t even have bells. Despite their objections, Bess marries foreign oil rig worker Jan (a warm, kind Stellan Skarsgård). When Jan is late to their wedding, Bess tearfully hits him in the chest with loose fists before he wraps her in a hug. She leads him into the bathroom during the ceremony, unable to wait for the promises of the wedding night. She looks directly into the camera with astonishment as her virginity is taken, appearing to receive a kind of sacred transcendence.

Bess is deemed simple and childish by the community around her, but instances such as these prove that both Jan and director von Trier don’t see her that way. Bess lives in a world where everyone is afraid of speaking their minds, where no one can see the world past rigid church traditions and social hierarchies. In contrast to this, she expresses exactly how she feels at all times, and has a vast appreciation for life itself, without consideration of how others feel about her. Having lost her brother before the start of the film, her faith in God is true and tested, unlike the old men who surround her. In a word, she lives with authenticity. Her purity in this respect seems almost otherworldly, but Watson embodies the role so completely that the character is kept in the realm of believability.

Cinematographer Robby Müller regards her with a sense of this credible life. Much of the film is shot in a very raw and spontaneous documentary style, fixated almost entirely on emotion. The shaky handheld camera follows acting over all else, mirroring the movements of actors to express the subjective experience of their characters. Scenes are given a jittery immediacy as constant jump cuts punctuate shots, sacrificing even basic rules of continuity for the sake of this unbroken concentration on acting choices. A great deal of the shots are intimate close ups, mostly on Bess, allowing Watson’s strong emotional rhythm to be captured beat by beat.

As can be gathered, she is granted the freedom to look directly into the lens of the camera at will. Sometimes this communicates playfulness, sometimes pain. Usually, it’s a profound sort of knowingness, which further establishes a unity between her and the lively style of the film. Superficial beauty is avoided at all costs in these visuals, with Müller even converting the 35mm negative to videotape and then back to film to deaden its color. Much of these jarring visual choices were brought over from von Trier’s Dogme 95 movement, which focused on eliminating the artifice of production value in films for the sake of emotionally honest storytelling. Though Breaking the Waves doesn’t fully conform to the Dogme manifesto, it unmistakably shares the movement’s spirit.

Bess, sunken into a deep despair over her husband’s extended departure to the oil rig, prays for his return at any cost. Jan is quickly sent home—after suffering a severe head injury during work on the rig. He is left paralyzed from the neck down, and Bess is left blaming herself, having asked God for his hasty return. It’s at this point that Jan, unable to make physical love due to his condition, makes her a dubious and unsettling request. He demands that she sleep with other men and tell him about it afterward, claiming that it is the only way he can recover. The remainder of the film has her grappling with the weight of this bizarre, perverse responsibility.

Jan’s request initially seems to come from a lack of hope in his own recovery. Thinking he may soon die, he wishes to help Bess move on. Knowing her piety and devotion to marriage, however, he understands that she will only do so if she thinks it will help him in some way. Thus, the impossible promise that it will somehow help cure him. But with his mind progressively rotting away from his injury, he seems to lose faith in this reasoning just as the viewer does. Jan becomes something like an enigmatic and incomprehensible God to Bess. She decides she must maintain her faith in him—that acting on his word must be right, even without being able to fully understand it.

And so, the film takes a deep dive into some rather depraved and humiliating sequences, with Bess’ faith in Jan tested at every corner. The hyperrealist style further serves to help the audience get a sense of the weight she carries, the despair in her decisions, by showing it all quite uncompromisingly. But even as the community around her shuns her for her actions, she never falters. This all leads to the fateful moments as she approaches the dangerous men on the barge.

The ugly, discolored, and raw style of the majority of the film is contrasted by title cards that separate each section. Beneath the chapter titles, each one is a static shot of a relevant landscape, from the oil rig to the rolling Scottish hills to Bess and Jan’s home. These shots are digitally manipulated by artist Per Kirkeby to bring out vibrant color and unspeakable beauty. In a film almost devoid of music, these cards are punctuated with especially moving pieces of ‘70s pop, by artists ranging from David Bowie to Rod Stewart. Though temporally insignificant in the film’s two and a half hour runtime, these moments lend an important mood to the film. Their perfection reassures the viewer of God’s presence in the naturalism of the rest of the film, easing the weight of Bess’ actions even as she descends into Hell.

Bess isn’t likely to resemble most viewers of the film. Her faith is hard to imagine being matched in the real world. The film is constructed so that these recurring cards allow the viewer into her mindset during more realistic moments, helping them to perceive a natural world in which God seems silent through the eyes of someone of pure faith. Only then can one see her martyrdom; the true meaning of her, perhaps everyone’s, suffering.