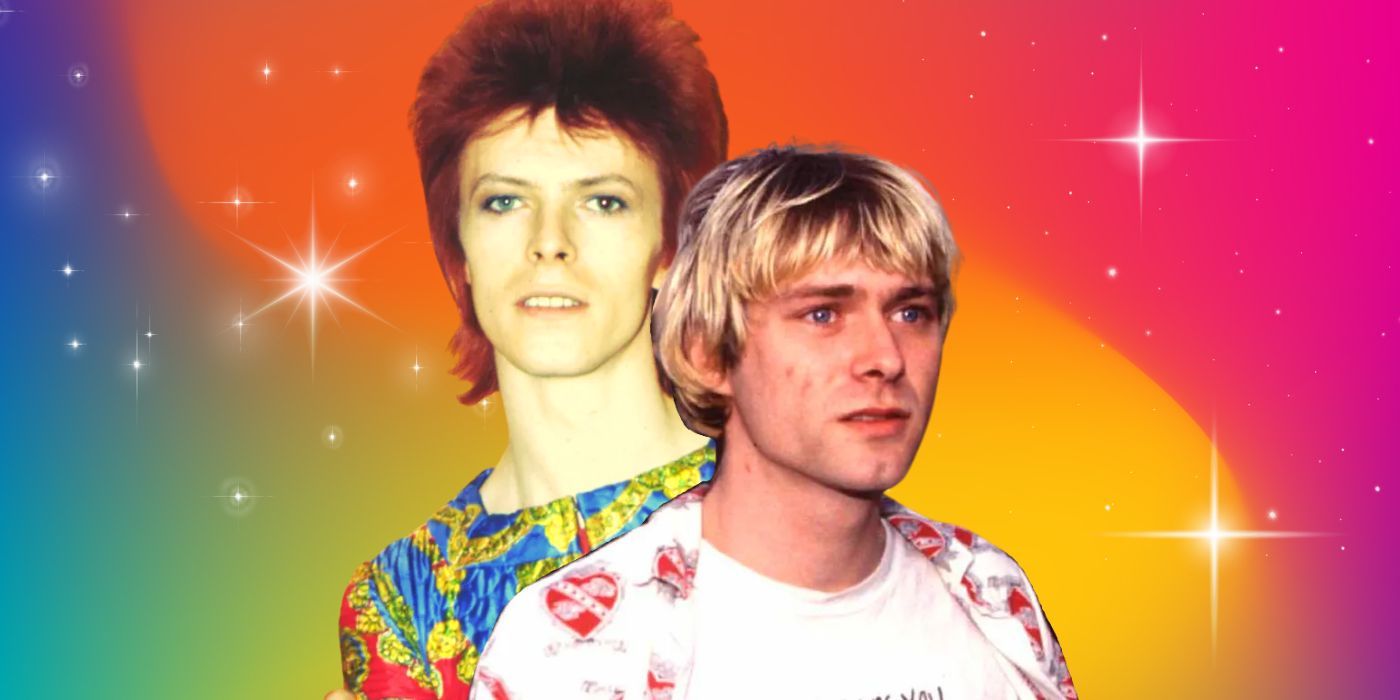

Documentary filmmaker Brett Morgen continually dazzles audiences with his immersive, loud, and spellbinding music documentaries. His creative use of archival footage, graphics, original animation, and interviews swirl together into movies that make viewers feel like they are inside the heads of his subjects. His latest doc, the David Bowie film Moonage Daydream, is a glimpse inside the mind of one of rock’s brightest stars, who always seemed to be on a journey to both understand and celebrate life. Bowie’s ever-changing life and public persona spoke to his belief that our time on this planet is a fascinating, thrilling, and complex journey.

By contrast, Morgen’s 2015 Kurt Cobain film Montage of Heck is almost an investigation into the psychology of a talented musician who tragically took his own life. While both films employ some similar creative choices, their subjects land on polar opposite ends of the spectrum, with one eager to keep living and the other feeling utterly despondent. By comparing and contrasting both of these films and their subjects, we’ll see how, paired together, these music docs make for a fascinating, existential, rock and roll double feature.

'Cobain: Montage of Heck' Challenges Visual Representation

Stylistically, Montage of Heck becomes both visually and thematically darker as the film progresses. Morgen’s talking head interviews with Cobain’s family and friends are initially shot with daytime lighting and end at nighttime. This serves as a visual representation of the story’s slow march towards Cobain’s untimely death. As other people help explain who Kurt was and how he saw the world, we also dive into his artwork, music, and writing to get a sense of how he saw himself. It’s an interesting contrast between Cobain’s narrative in his own mind versus the story being told about him.

The Immersive 'Moonage Daydream'

Moonage Daydream does away with third-person interviews and instead allows David Bowie to speak for himself via archival interview bites. At the same time, Morgen creates a visually stunning representation of Bowie’s mind. We see Bowie roaming the world, dancing, performing, and painting. Moonage Daydream is more immersive than Montage of Heck and even more subjective. The truth being revealed to us is entirely Bowie’s truth, not anyone else’s. This decision to represent only the protagonist’s subjective truth is reminiscent of Morgen’s 2002 film The Kid Stays in the Picture, which was his first experiment in an unorthodox documentary filmmaking style that has continued to evolve and become more radical, peaking with Moonage Daydream.

Morgen's Filmmaking Choices

These similar but notably different filmmaking choices may, in part, be the result of how Cobain and Bowie ended their lives, one with gusto and the other with a feeling of hopelessness. It’s not necessary for others to comment on Bowie’s death as he did it himself in his work. Cobain’s flame burned brightly and then was suddenly extinguished, leaving the world shocked and mystified. His decision to end his own life doesn’t feel like a satisfying conclusion or philosophical statement, it just feels more like a momentary lapse in judgment. Yet, Morgen does a superb job showing us how Cobain arrived at that moment by utilizing his immersive style to great effect. By understanding his perspective, it leaves the audience with a lot of questions as to how such a tragedy could’ve been averted. Why does someone decide to end their own life and is there something the people close to them can do to prevent such a decision? What exactly fills a life with meaning, and how can a meaningful life be sustained?

Moonage Daydream feels much less like a question to be answered and more like a definitive statement. Bowie tells us that life is a wonderful experience, and he wishes he could go on living it. The film opens with a quote from Bowie musing about what humans are supposed to do if God is dead, as Nietzsche once declared. After a lifetime of spiritual exploration and reinvention, the answer from Bowie’s perspective seems to be just that: journey, change, and curiosity. Moonage Daydream is about as life-affirming as a film can get. If there is any question whether life is worth the trouble, Bowie’s answer is an enthusiastic “yes!”

The very different tones of these films may resonate with different types of audience members. Perhaps some will identify with Kurt’s mental health struggles, while others practically leap out of their seats with joy during some of Bowie’s performances (at least a couple did at a recent IMAX screening in Los Angeles). Or perhaps the films will hit differently depending on what each individual audience member is going through in life.

Regardless of which film resonates more, they both take their audience on a roller coaster ride that makes the theatrical experience feel alive and vibrant again. And both films share one defining quality: they are loud. Not just turn up the headphones loud, but full-on Spinal Tap “these go up to 11” loud. It’s rare that a film screening has the same energy and assault on the senses as an actual concert but these two films definitely do. If at all possible, view them on a giant screen with the loudest speakers currently being manufactured.

Until you’ve seen a Morgen film, you haven’t really experienced what documentaries are capable of. So carve out some time to watch these films back-to-back. Taken together, Moonage Daydream and Montage of Heck are like a complete yin and yang of existential, rock and roll filmmaking.