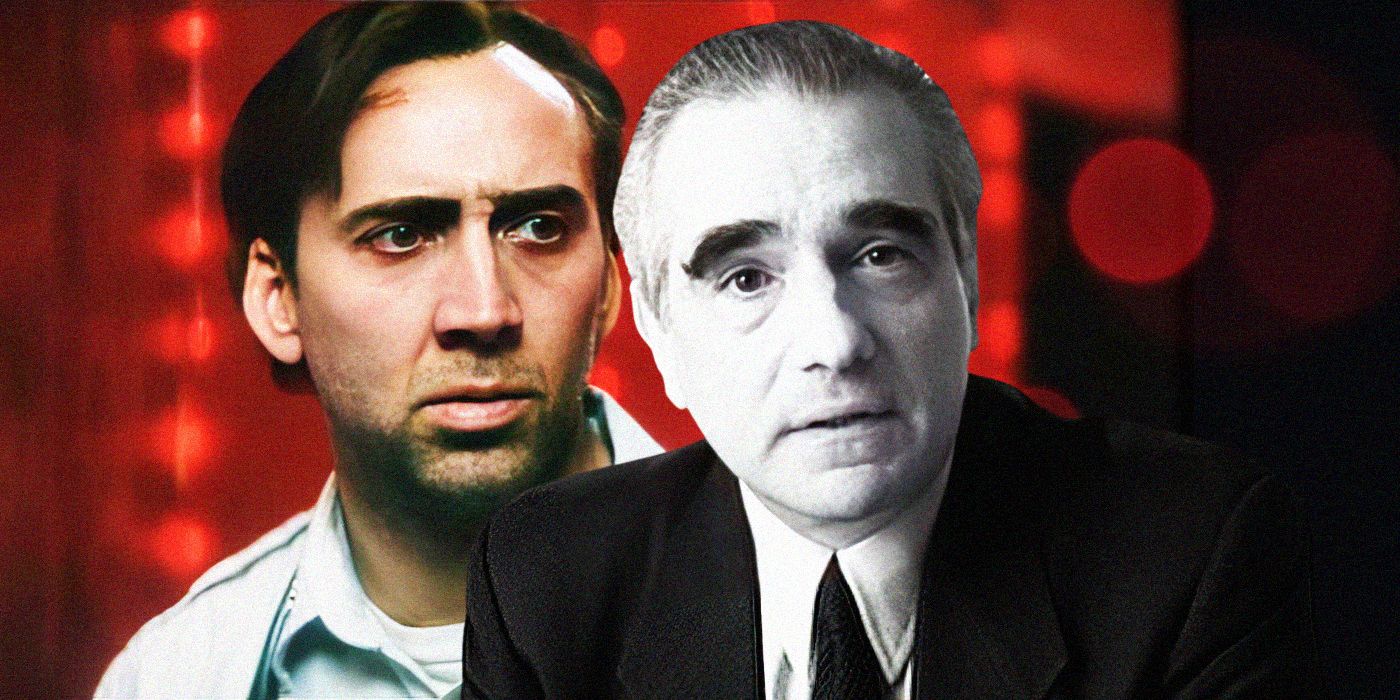

When counting down Martin Scorsese’s top five, there’s no doubt that the likes of Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and Goodfellas will crawl into pretty much every fan’s list, but his lesser-seen, wildly unhinged Bringing Out the Dead was actually dubbed by its star Nicolas Cage as one of the best movies the superstar actor has ever made. No matter how you feel about the A-list star, and regardless of the method used to rank his movies, when the list includes the likes of Face/Off and Leaving Las Vegas, that’s no small feat of praise. But what is it about Bringing Out the Dead that makes it so revered by its fans? More importantly, with a lukewarm critical reception and box office performance, what held this one back from being appreciated among Scorsese’s best?

Written by Paul Schrader (who’s now flourished as a director) and released in 1999, Bringing Out the Dead follows a depressed, burnt-out, insomniac paramedic (who else but Cage) as he rides through the streets of New York City attempting to save as many lives as he can, all the while haunted by the ghosts of those he’s failed. The world of New York’s 24-hour healthcare staff that lives by night is shown in grim and grimy detail. Certain characters are slaves to bureaucracy, others are slaves to drugs and alcohol, while some have incredible faith in the fact that they’re doing the Lord’s work, saving the lives of sinners throughout New York City (and you can bet that when Paul Schrader writes New York City, he’s emphasizing the sinners).

‘Bringing Out the Dead’ Is One of the Best Depictions of Burnout Ever Put to Film

It’s easy to see why Cage responded so well to his role in Bringing Out the Dead specifically. The film is one of the greatest showcases of burnout in an unforgiving job of all time, resulting in a character that perfectly encapsulates the leading man’s over-the-top eccentricities with a plot so tonally heavy that it also demands a subdued sensitivity. This is a performance entirely at odds with itself, but in a way that fits within the character of Frank Pierce’s particularly hellish concoction of problems. Cage looks nothing less than absolutely exhausted throughout, haunted by the demands of the job which is slowly sucking away his soul and his character knows it.

Staying in the job is certain death and Frank does whatever he can to get fired, whether it’s turning up late, calling in sick, or pushing back on taking rescue calls at nearly every turn even though someone’s life is always at stake. Even after intentionally putting himself in a position where he’d be fired, literally reminding his boss of his “promise” that he’d fire him if he were late again, his boss blows him off, falsely promising to fire him the next week instead in a darkly comic reversal of employer/employee dynamics.

'Bringing Out the Dead' Draws a Powerful Analogy Between Altruistic Jobs and Fatal Drug Use

This begs the question, why doesn’t Frank just quit? In spite of the fact that he was once known as ‘Father Frank’ for his altruism, the answer isn’t entirely moral. In his opening narration, Frank states that “Saving someone's life is like falling in love. The best drug in the world.” This makes for a remarkable conflict of character. Frank is literally addicted to the rush of saving a life in spite of the fact that he knows it’s killing him. With every soul he saves, a little piece of his is regained, but with every life lost, that’s another failure that becomes increasingly hard to justify as just a bad day at the office.

The film solidifies its metaphor through a new brand of heroin introduced onto the streets, so fatal it’s dubbed "Red Death." If you think that name alone would put the populace off to its consumption, think again, as Frank finds himself saving several people from the drug throughout his nightly excursions. As with any dangerous drug, the lows always outweigh the highs, yet millions in spite of that knowledge fall victim to its prey every day. It’s an unflinching look at addiction that rivals even the best, using a habitual practice entirely unique to express it.

Fitting for a Movie About Death, Religious Metaphors Run Throughout 'Bringing Out the Dead'

It wouldn’t be a Scorsese/Schrader joint without a heavy dose of religion interspersed throughout. Scorsese, who always wrestled with his Roman Catholic roots, is candid about how often he was ill in his youth (crediting his frailty to the sheer number of movies he was able to consume). When describing his own personal connection to the film’s subject matter, Scorsese stated, “I had 10 years of ambulances. My parents, in and out of hospitals. Calls in the middle of the night. I was exorcising all of that. Those city paramedics are heroes — and saints, they’re saints.” What’s interesting here is the implication that Scorsese grew up among the mania of frantic paramedics attempting to save a city’s worth of people every night, as well as the religious language he uses in describing his connection to the piece, something on full display in the piece itself.

Aside from the obvious allusion to faith in the character’s former moniker ‘Father Frank,’ Ving Rhames plays an evangelical paramedic who literally saves a victim’s life through a mass prayer (in another scene that’s oddly humorous as well). More importantly, the character through which Frank’s soul is saved is appropriately named Mary (Patricia Arquette), who embodies the role of both Mary Magdalene who Jesus cleansed from seven demons (Frank finds Mary in a drug den after her father is put on life support), and the Virgin Mary (embodied in their final resting position as Frank’s connection to Mary has lifted him from his guilt). Scorsese reinforces the religious connotations visually as well, constantly painting his scenes with an ethereal white light that increases in intensity throughout.

The divinely white lights can be interpreted a multitude of ways. When they’re on Frank, it seems to suggest that like the patients he’s been unable to save, Frank is becoming more and more of a ghost as the job devours him. What’s also interesting is the source of these lights, often motivated by the lights of New York City, the likes of which is depicted as overwhelmed by sin. Towards the end of the film, there’s a moment when a dying drug dealer confuses the sparks made by a cutting tool with fireworks, marveling at their beauty. This goes to show that even in the most desolate and filth-ridden of situations, beauty and by extension, God, can be found.

Legendary editor and long time Scorsese collaborator Thelma Schoonmaker states that part of the reason Bringing Out the Dead didn’t find the audience that other Scorsese movies did is due to the fact that it was falsely marketed as a car-chase movie. Even if the film features enough adrenaline to contend with the likes of Fast & Furious, with such dour subject matter and an ending that’s just as morally controversial as what precedes it, it’s easy to see why this wasn’t as broadly marketable as The Departed or The Wolf of Wall Street. Nevertheless, for proper Scorsese fans, the film is a must-see. While it may be dissimilar to what the director’s fans expect, there’s no denying that he’s never taken a swing this visually, tonally, and thematically bold.