Funky, oddly mixed prog-rock blasts the eardrums, sometimes cutting off abruptly during a particular smash cut. Martial artists and actors brawl each other in run-and-gun wide shots that sometimes careen into crash zooms, their rubber weapons obviously bending, their sound effects unsynchronized and inaccurate. And Bruce Lee, during one mini-climax, fights a series of flying dogs — canines trained by the villain, canines sold to us via choppy inserts of obviously stuffed paws being flung at one of our greatest screen presences of all time.

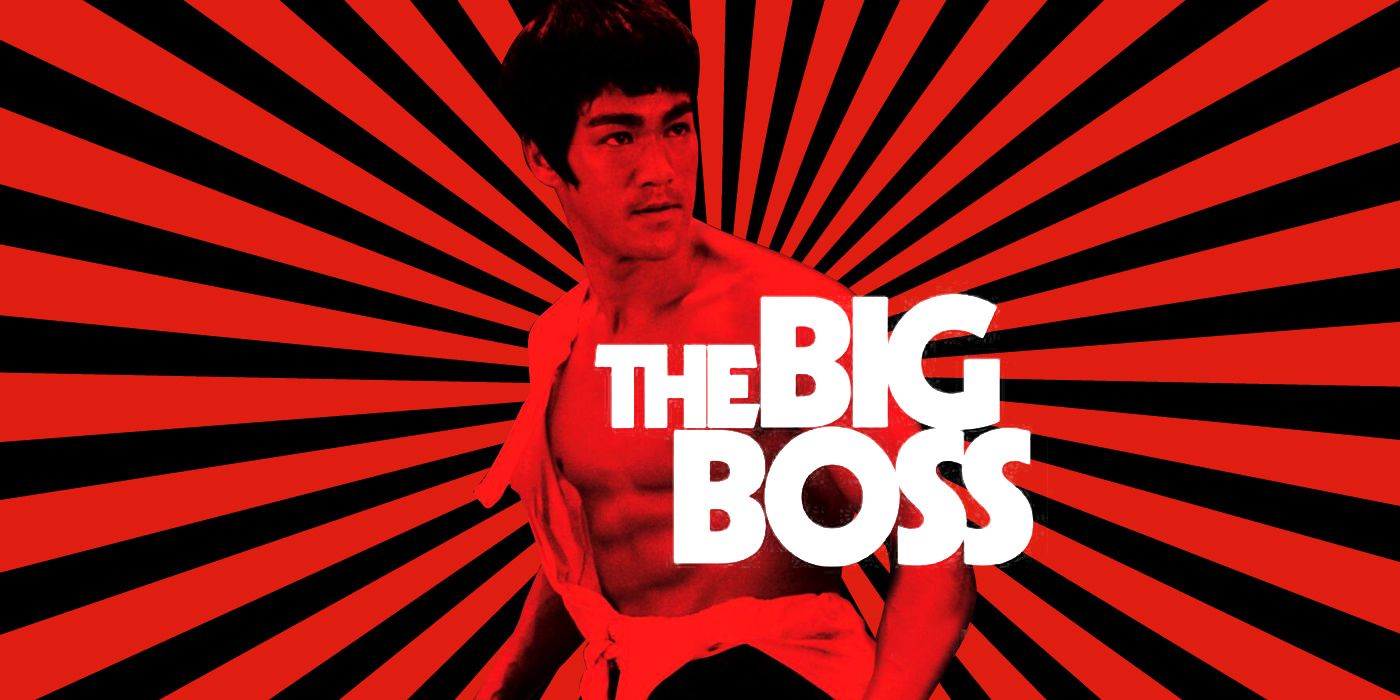

The Big Boss sounds like a deliriously campy, entertaining, and fluffily fun action flick, no? It is all of those things, to be sure, and an essential watch for martial arts fans who haven't dived as deeply into Lee's career as they'd like to. But among these signifiers of goofiness lies — pretty gosh-darn explicitly, actually — a pained, incendiary, screaming treatise against the exploitation of the working class by the financially elite. The Big Boss promises you the bubblegum of a grindhouse kung fu flick, then gives you the medicine of radicalized political progressivism. It's quite the feat, making for quite the unique action experience.

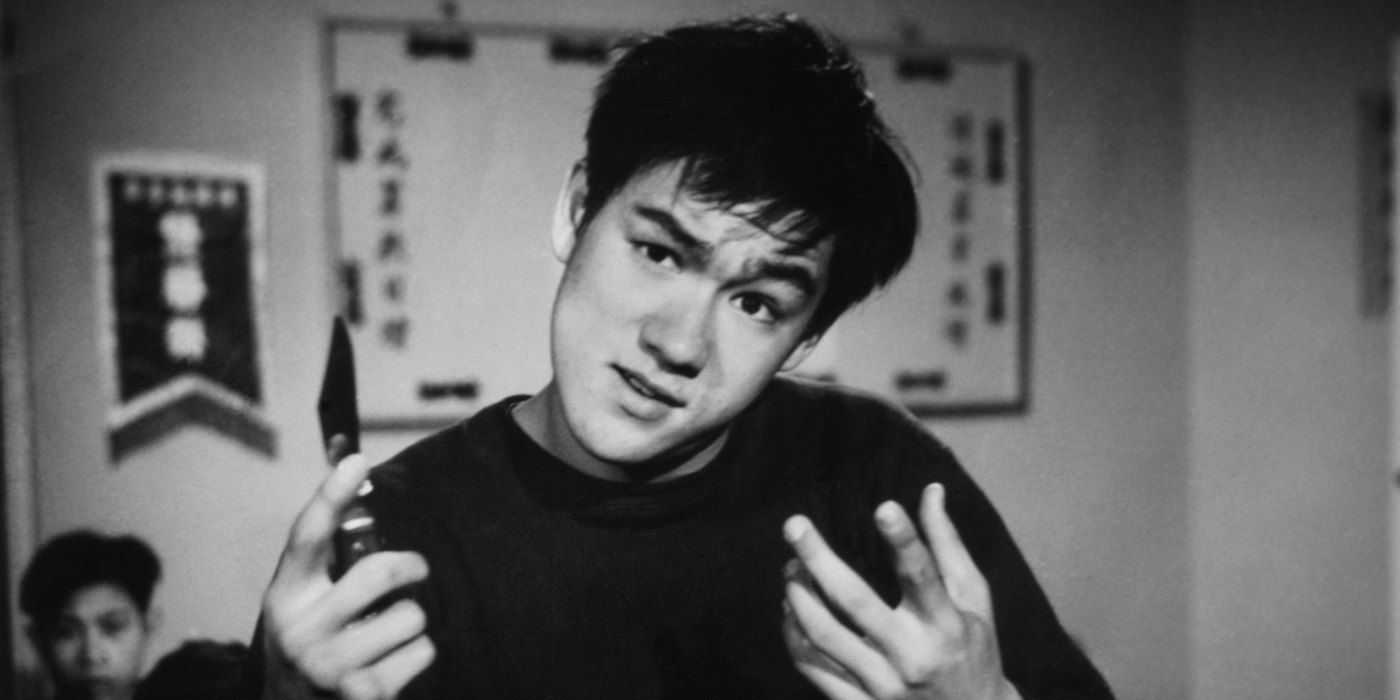

Lee does not play the titular big boss. That (dis)honor belongs to Han Ying-chieh, whose Hsiao Mi is the head of an ice factory that Lee's poor, humble, and ostensibly non-violent Cheng Chao-an finds a job at just to stay afloat and help his family as best he can. From the gate, director Lo Wei aligns us with the plight of the working class, casting an incredibly charismatic, talented figure as our low-status hero and making our high-status villain as lecherously rendered as possible. Wealth and power do not equate a level of spiritual success in The Big Boss; we see much more aspiration in the simple-but-gritted life of Cheng. We want, from frame one, our working-class comrades to win and our elite-class enemies to fail (and what exactly happens in frame one? A big bully smacking around a little kid just trying to sell food for his family, refusing to pay him, wanting instead to hoard wealth and resources while exploiting the labor that made it possible).

Granted, by 1971 when this film originally was released, there were already countless films using this proportional position of power and sympathy as a default (and, like, storytelling since ancient times). But The Big Boss takes it all further by centering its plot moves and fight scene justifications around clearly-stated labor disputes, power struggles, effectively-utilized strikes, and an obvious opinion on state-sanctioned, money-oriented power being a force for evil.

When Cheng joins his fellow workers at the ice factory, the way they communicate with each other speaks of their inherent humanity for one another. Cheng is cousins with Hsu Chien (James Tien) who also begins working at the factory before getting murdered for poking around where he shouldn't be poking (a violent heightening of an experience that has already been rife with micro-exploitations and bald-faced labor violations). As the rest of the workers organize and investigate, they all begin using the honorific "Brother Hsu," regardless of any actual blood relation. They aren't just co-workers; they're bonded together in opposition to unspeakable forces of oppression. Conversely, whenever our workers speak to their superiors, they only use job titles like "Manager" or "Boss." And when these higher-ups speak about their employees, they specifically use dehumanizing language (i.e. "Keep an eye on that one!" instead of a personal pronoun). Whose side are you naturally gravitating toward?

Cheng eventually organizes his fellow workers into a strike, demanding better working conditions and information on their missing brother Hsu, earning advancements for the workforce and becoming a foreman in the process (did he have to fight people with his fists and feet to earn this? Who can say). But this victory is soon seen as pyrrhic, The Big Boss revealing the depths of its honest cynicism about how corporate interests and the greedy propagators therein use vessels of "change" for their own devious machinations.

Now that Cheng is a foreman, he does his best to leverage this new power into securing a meeting with the Big Boss to find out where the hell Hsu is. Instead, his manager, whom everyone simply refers to as Manager (Chan Chue) invites him to a fancy dinner and tempts him with the earthly pleasures of money, alcohol, rich food, and easy sex that come with such exploitative practices. Cheng, whose upbringings we've seen as being so humble, is indeed swayed by this evening, forgetting to put his foot down and demand the return of their comrade, instead getting drunk off his tuckus and bedding a provided prostitute (Marilyn Bautista). When Cheng returns to his workers with nothing to show for his "inside track," they berate him, rightfully so. "Dinner?" they passionately shout. "So you forgot about your brother Hsu?" He did, indeed; he became so swept up by the elite class' weaponized distractions of fun that he briefly sold his morality (worker solidarity) to the devil (the rich promising false victories for a lucky few).

Cheng vows to never fail in this matter again. And when finds out this ice factory murdered brother Hsu and is, in fact, a heroin-pushing facility (a whistle blown by Bautista's character who reveals she used to be their maid; another example of the film showing how the working class can and should destroy an elite class sworn to destroy them), he vows to get revenge by any violent means necessary. Their climactic showdown (not the one with the aforementioned flying dogs, mind you) is lensed and fought with a kind of balletic brutality, full of intention and blood and kineticism. It ends as you might expect a film in which Bruce Lee fights a bad guy to end — until one final, politically acerbic twist of the knife.

For our most powerful, corrupt, state-sanctioned systems to keep functioning, exploitation of the working class is necessary. So when Cheng, a muckraking fighter who has the ability to kick ass by himself while also organizing his fellow workers into units of change worth fearing, destroys this high-profile symbol of the degraded elite, the state-sanctioned systems come down on him. The Big Boss' final frames before hitting us with that "The End" title card are not those of celebration or catharsis. Instead, they are of Cheng, covered in blood, sweat, and tears, defeatedly putting his hands up for the police to arrest him.

It's a paralyzing, somber, and breathtakingly dark ending to a kung fu flick about stuffing heroin in ice. It's a stark taking of our societal temperature about the structures of wealth and power we let rake us over the coals, taking their scraps of money and pleasures as "good enough." And it's a rabble-rousing call to arms for the people to recognize that they have the power to ensure a happier ending for their siblings in arms.

And it has flying dogs. Perfect movie, 10/10, no notes.