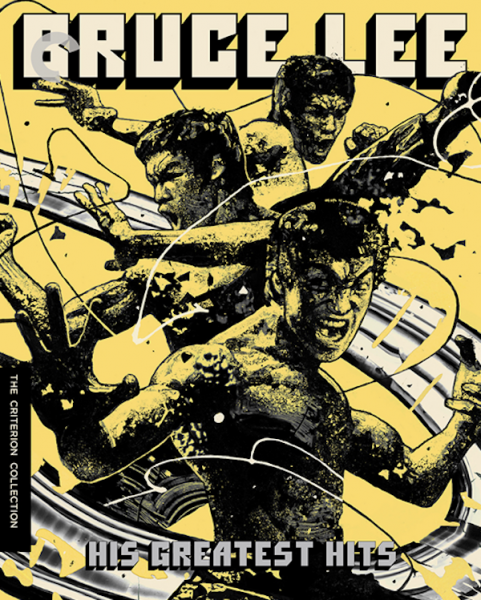

Even if you’ve never seen a Bruce Lee movie, you know who Bruce Lee is. That’s the impact of an icon. You probably know the vague outline of Bruce Lee as a martial artist who died young and would notably caterwaul as he fought his opponents on screen. But when you make your way through Criterion’s new Blu-ray collection, Bruce Lee: His Greatest Hits, you get the full picture of a man who changed action cinema forever, and the tragedy that we only saw a glimpse of what he was capable of doing. I’ve spent the past week watching Criterion’s box set, which, like all Criterions, includes a wealth of special features, but what really jumped out at me were the movies themselves.

Before we continue, a brief bio on Lee: he never really belonged anywhere he went. He was a child star in Hong Kong, but because he was born in America, he was considered too American. When he tried to make it in Hollywood, he was considered too Chinese. The biggest splash he made was as Kato in The Green Hornet, but that show was canceled after one season. It wasn’t until he went back to Hong Kong that he discovered that The Green Hornet had opened the door and gave him an opening to make movies that would allow him to present his martial arts philosophy of Jeet Kune Do, which is a mix of other martial arts driven by an individual’s own style and what’s needed to win the fight.

While in Hong Kong, Lee would make three movies: The Big Boss, Fist of Fury, and The Way of the Dragon. Each movie would shatter Hong Kong’s box office records and further establish Lee as an international star, especially The Way of the Dragon, which Lee wrote and directed. These films were big enough to finally get Hollywood’s attention, and they made the star vehicle Enter the Dragon. Lee died of a cerebral edema a month before Enter the Dragonopened, and never saw it become a massive success. Before Lee died, he shot about 30 minutes of usable footage on his next project, Game of Death. Five years later, that footage was repurposed into a Bruce-sploitation picture that relies heavily on a body double and footage from Lee’s previous movies until you get to the famous pagoda sequence where the real Lee emerges.

When you watch all five films in sequence, they tell a story about Lee’s origins as an icon. Again, there’s a fuller picture here that the Lee documentaries and biographies reveal about a kid who didn’t really fit in anywhere, who got into street fights, who trained celebrities in martial arts, and finally made an impact with martial arts cinema. But if you were to watch only these five movies, you’d still get a clear picture of who Lee was on screen and what he represents.

In The Big Boss, you can see a studio still uncertain if Lee can carry a picture. For the first act, you have a two-hander where Lee shares the screen with James Tien, and it isn’t until Tien’s character is killed off at the end of the first act and Lee’s character, Cheng Chao-an, is allowed to fight, that the power of Lee emerges. You can also immediately see that Lee isn’t here to draw out a fight. While his contemporaries in martial arts cinema were about grace, movement, and choreography, Lee wants to show how to win the fight. He’s about quick, brutal movements that instantly down an opponent, and it gives all of his fights across his movies a hard-hitting impact that was foreign to movies until that point.

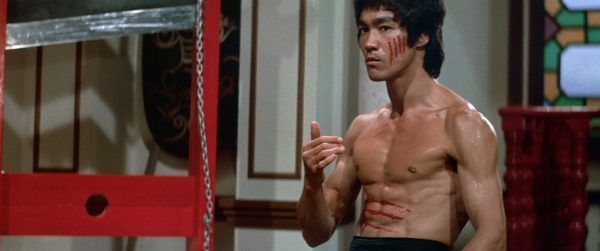

When you move to Fist of Fury, you can see that the studio is giving Lee a lot more latitude to make the kind of movie he wants to make. Gone is the tonal schizophrenia of The Big Boss where a guy gets cartoonishly knocked through a wall and his outline remains. Instead, Lee really leans into the “fury” of the title, and his character, Chen Zhen, goes on a mission of revenge against the Japanese martial arts school that poisoned his master and attacked his fellow students. When you watch Lee take down a dojo full of martial artists, you can see that he’s a fighter like none other and that everyone who followed is kind of standing his shadow. Movies simply weren’t made like this, and Lee combined movie star charisma (I can’t stress enough how much the camera loves him) with martial arts expertise.

The fullest expression of Lee that we got in his all-too-brief career was in the film he directed, The Way of the Dragon. The plot, like all other Lee martial arts movies, is very clear about the good guys and the bad guys, but with its Italian setting and Chinese heroes, you can see Lee clearly setting up a work of international cinema to make himself a star on the global stage. What’s astonishing here is that it never feels like Lee is making a retread of his previous movies. Perhaps on a long enough timeline, Lee would have repeated himself, but the fights here feel fresh, especially when Lee squares off against a hired goon played by Chuck Norris in the Roman Colosseum. The Way of the Dragon is the clearest expression of Lee showing that he can use fights to inform character and develop the plot, not just as an empty set piece.

Enter the Dragon is Lee’s most successful movie in terms of box office and recognition, and yet I have a bit of ambivalence towards it. It’s the movie where Hollywood showed they were finally ready for Lee, but even here, you can see them hedging their bets by setting up three protagonists with Lee having to stand alongside John Saxon and Jim Kelly. Rather than trusting that audiences would respond to Lee solo, we have to sit through scenes with Saxon and Kelly, which take us away from the beating heart of the picture, Lee playing a James Bond figure who’s going to take down a criminal mastermind. There’s an undercurrent of frustration that runs through Enter the Dragon, which is good in a vacuum, but when you look at it as part of Lee’s filmography, it feels like it’s failing to give its strongest aspect the full attention he deserves.

Since Lee died so young (he was only 32 when he passed), you can’t help but feel an added tragedy to these pictures. You can see that there was so much more for Lee to accomplish, and instead his memory was exploited for something like Game of Death. That film stands out among other Bruce-sploitation movies since Lee was actually involved with the project at the time of his death, but the finished project is pretty gross. It relies heavily on a body double and the plot, which is about an accomplished actor faking his death to go after the bad guys, uses footage of Lee’s real funeral. The whole endeavor feels crass, and it can’t help but leave a sour taste even as you appreciate when the real Lee shows up at the end to wail on his opponents.

When you look at these five films together, you see someone changing the game through his artistry. It took someone like Lee who didn’t “belong” anywhere to show that he belonged everywhere, and that cinema would never be the same after he made his mark. Action cinema as we know it owes a huge debt to Lee and his philosophy of personal expression through martial arts. It’s easy to parody Lee because he’s an icon, but this box set shows why his iconography matters. He completely changed how Chinese actors were allowed to be presented on screen. No longer were they dismissed as servants or nefarious villains, but they could be the hero and a sex symbol. Lee had to work to carve out a place for actors like him, but cinema was never the same afterwards.