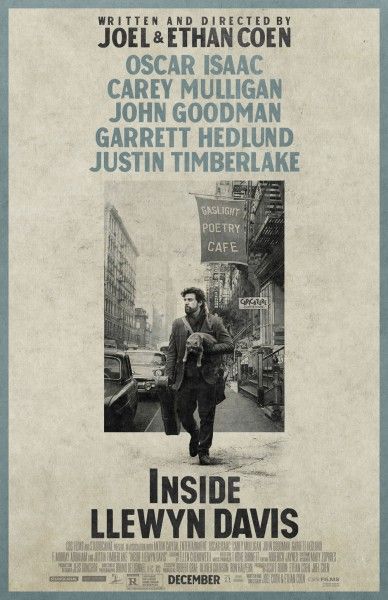

From Academy Award winners Joel and Ethan Coen, Inside Llewyn Davis follows folk singer Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac), who is struggling to make it in the Greenwich Village folk scene of 1961. Relying on friends for a couch to sleep on and scrounging for whatever work he can find, Llewyn attempts to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles, many of which are of his own making, while never really catching a break. The film also stars Carey Mulligan, Justin Timberlake, John Goodman, Garrett Hedlund, F. Murray Abraham, Adam Driver, Stark Sands and Max Casella.

At the film’s press day, cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel (Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, A Very Long Engagement, Amélie) spoke at this roundtable interview about what it’s like to collaborate with the Coen brothers, doing his own research and giving suggestions, where he got his vision for the film, creating a mood, working with filmmakers he can communicate with artistically, his desire to work with directors who use cinema as a language, and the most difficult scene to shoot. Check out what he had to say after the jump.

Question: When you collaborate with the Coen brothers, do they give you reference material, or do you do research yourself?

BRUNO DELBONNEL: Whoever I work with, I do my own research and I suggest things. Their main reference was to have a New York, slushy, wintery feel to it. That was the only reference they gave me. And then, they let me do my own research and I brought them some ideas.

In the course of your research, what gave you your vision for the film?

DELBONNEL: It’s funny because I was shooting Dark Shadows when they called me for this, so I was really busy on that. They said, “Okay, read the script and we’ll call you in a couple of weeks.” I had to work because I couldn’t have another phone call with them without having read the work. So, I did some research and I found The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album front cover of New York, which is what I thought they were looking for. And when they called me, I said, “I saw this album,” and they said, “Yeah, that’s exactly what we had in mind.” It was easy because that front cover was exactly what they were talking about. It was like I was bringing something that was a perfect match. After that, it was all about the research I did. I’m really interested in abstract painting, and things like that. It was about the color palette and the density. I brought some Mark Roscoe paintings. The feeling in his paintings is absolutely brilliant and beautiful, so we discussed that. I asked what they thought of those color compositions and that kind of framing. It was more like that than a straight reference. If you use straight reference from the ‘60s, then you’re locked into something that is a period look, which is not interesting.

How do you use color and shadow to create an atmosphere for your movies?

DELBONNEL: I try to create a mood. What is a mood? A mood can be sad, happy, or whatever. But, on all the movies I’ve done, I’ve tried to find a concept. It’s very intellectual, but it’s not, in some ways. For example, I was shooting the sixth Harry Potter movie, and there were five previous movies, so it was about, “What can I do to make it look different?” I thought it could be like a music score that is just a variation of something. And then, you add some very bright colors to break the monotony of everything. On this one, it was very dark and bohemian. It was all about Oscar, on stage. It wasn’t about the audience. So, Oscar was lit, but there were shadows. You want to see something, so it’s not totally silhouette. And there was smoke because they were smoking like hell. There were some references you needed to see, and that’s how I light, as well. It’s about the story. One shot has a purpose, and that purpose is the story. It’s about what the shot is saying. I’m just telling the story with light.

How did you get yourself to a place where you could work with the directors that you wanted to and communicate artistically with them?

DELBONNEL: I don’t know. That’s how I started. If you see my resume, in 20 years, I think I only did 12 movies. I just pick the ones I want. I’m just trying to do something where I’m happy. I don’t want somebody telling me, “You’re gonna put the camera here. You’re gonna light this way.” That’s boring. It’s like working in a factory, but with a high salary. I think photography is an art. When I read a script, I try to find a good script where I can do something that is not noticeable. The purpose is not to be noticed. It’s just to give something to the movie, so that it becomes a piece, like a painting. I’m fortunate that I’m a really lucky man because I’m working with these guys.

This is your second collaboration with the Coens. What is it about their style that stands out for you, and that you gravitate towards?

DELBONNEL: I don’t know. They are unique. That’s a very hard question. I don’t know how to answer that. I’ve worked with Tim Burton and Aleksandr Sokurov, and they are the opposite. What is interesting is that they are aiming towards something, which is using cinema as a language. There are maybe 20 amazing directors in the world, and that’s it. The rest are crap. When I say crap, they just do coverage, and then they edit the movie and expect that it’s going to be a success. But, people who use cinema as a language are the masters, and I’m fortunate to have worked with some of them. What was surprising when the I read the Inside Llewyn Davis script was that it was a very sad comedy, but was nothing special. When I saw the movie, I said, “Oh, god, those guys are brilliant.” There is the script, and then you shoot, and then you see the final product, and there can be a big gap. With this, suddenly, the movie just opened up and it was stunning. I was really shocked.

As a cinematographer, how did you adapt the way you shoot to best recreate the 1960's for this film?

DELBONNEL: That’s a good question. I don’t try to recreate anything. I’m looking forward, not backward. The ‘60s in Paris were totally different than in New York. New York is a very special city, as Paris is a very special city. They have their own vibes. I grew up in Paris, which has nothing in common with New York. Paris in the ‘60s was far from New York, in distance and in culture, as well. So, I didn’t try to do a period movie. When I did Across the Universe, it was a period movie in the ‘60s, but it’s not interesting to recreate that. Should we use Kodachrome or a vintage camera to recreate something? That’s dull. It’s more about the mood. The mood is much more interesting. So, the mood of Inside Llewyn Davis was about a sadness. That’s what I tried to do, on this movie.

What was the most difficult scene for you to shoot?

DELBONNEL: The most difficult was the shot at night with the car, when they are on the road. It was freezing. It was difficult because it was a low-budget movie. Harry Potter was $250 million. This one was $11 million, or something. I was like, “Okay, I’m going to do like Harry Potter and put light here,” and they were like, “What are you talking about? We don’t have the budget for that.” So, it was just about trying to find something very efficient and fast and beautiful. I was lucky. It was a foggy night, which helped everything. But, it was difficult because I took a lot of risks. It really was on the verge of seeing nothing. That’s a bit risky. They could have fired me after that.

Inside Llewyn Davis is now playing in limited release, and opens nationwide on December 20th.