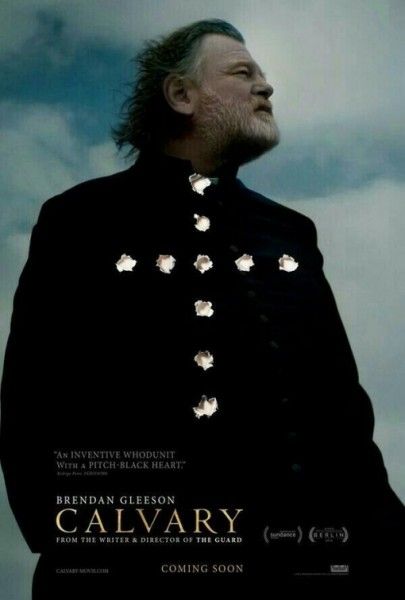

[This is a re-post of my review from the 2014 Sundance Film Festival. Calvary opens today in limited release.]

The Catholic Church can give absolution to sinners who feel true repentance. The Church is a vessel for God’s forgiveness. But their cover-up of sex abuse was, by the morals of any civilized human being, unforgivable. John Michael McDonagh’s Calvary is a dark, complex, and demanding meditation on faith, the limits of forgiveness, the necessity of compassion, the possibility of absolution, and inevitable reckonings. Anchored by yet another incredible performance from Brendan Gleeson, Calvary is the rare film that shows the intricacies of religion without becoming pedantic in the process.

Father James (Gleeson) is taking confession on a Sunday when a confessor says that he was sexually abused by a priest for years. The priest is now dead, and the confessor explains that killing an evil priest wouldn’t get anyone’s attention anyway, but killing a good priest will make people sit up and take notice. The confessor gives Father James one week “to get his affairs in order”, and then he’ll be killed. Rather than prepare for the end, Father James goes about his daily business of attending to his rural community, also bringing comfort and counsel to his daughter (Kelly Reilly), who has recently attempted suicide.

Whether Father James knows his confessor or not is unclear. We know that these priests can see the confessors (a fellow priest at the parish talks about a specific congregant’s unusual sins), but there’s also the possibility that Father James didn’t look through the confessional window (I’ve never been to confession, so I don’t know how transparent the windows are), doesn’t want to out the congregant (even though his superior says that the conversation doesn’t qualify as an official confession, so it doesn’t have to be kept confidential), and/or he believes that the confessor will change his mind.

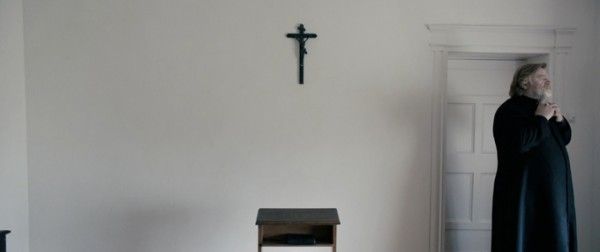

I like that last explanation because it is a true test of faith. Rather than bring in the police, Father James refuses to let his life be completely upended by this threat, not because he’s tough or thinks the threat is idle, but because he is responsible to his parish, not to his self-preservation. Thankfully, the film never overtly states that Father James is behaving Christ-like, and he certainly doesn’t have the attitude one would expect from someone demonstrating that behavior. As we see throughout the picture, actions are more important than appearances.

Going through his congregants, Father James meets with people tiptoeing around repentance, but looking for a shortcut. They want the absolution without the reckoning. Father James meets with a serial killer who half-jokingly says he can’t remember where he buried one of his victims; James tries to reason with an adulterous couple who brush him off completely; he barely tolerates a wealthy man who thinks he can buy his way into heaven even though the last time this service was offered, it led to the Protestant Reformation.

While these conversations could have been incredibly dry and (forgive the pun) preachy, McDonagh always plays to the characters’ feelings. There are no lectures or open meditations on the nature of faith. The emotions give weight to the themes because faith is incredibly personal. It relates to the soul, to salvation, and to damnation. Watching the characters grapple with their fate and the role of God in their lives is powerful when handled correctly, and McDonagh has the maturity and intellect to handle this topic respectfully without being stodgy or dogmatic.

The entire cast is terrific, but like his previous collaboration with McDonagh, The Guard, Gleeson is at his best. The range of emotions he has to play is astounding, but Gleeson is never showy even when the character is at his most fragile and frustrated. It a performance that is equal parts warmth and weariness, and that combination is key to understanding the character. With hardly any exposition, Gleeson’s performance lets us know his beliefs and his experience working at a parish where people attend church, but rarely follows its teachings. It is a life of futility as people come in for Father James’ approval instead of demonstrating true repentance. He’s trying to provide more than a function, but no one is willing to do the work, and what good would the “work” do anyway?

When the confessor tells Father James to get his affairs in order, it’s an impossible task. The movie asks if anyone can ever get right with God. If the only way to get right is through forgiveness, and the institution designed to provide forgiveness does something that any right-thinking person believes is unforgivable, then is salvation even possible? Calvary doesn’t opt for an atheistic approach where the solution is to turn one’s back on religion, although it does let the village’s atheist (Aidan Gillen) have his say. Rather, McDonagh is interested in forcing the audience to seriously wrestle with the nature of forgiveness and the limits of faith, which is far more rewarding than an angry screed against God and the Catholic Church.

Calvary is not an easy movie, but it’s not a punishingly harsh one either. It has moments of wry humor, people who genuinely want Father James’ help, the constant mystery of the confessor’s identity, and it’s all contained in the gorgeous Irish landscape. The beauty of the world never fades away even when faith begins to waiver, and it’s a reminder that damnation isn’t inevitable even when repentance seems impossible.

Rating: A-