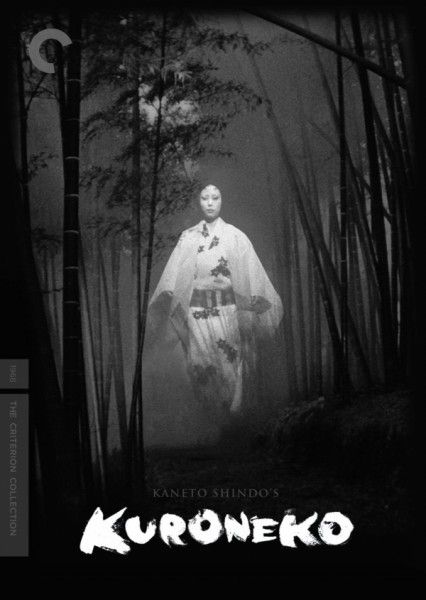

Criterion most recent output is a treasure trove for fans of films and the collection. 2010’s Carlos is Olivier Assayas’s portrait of the terrorist Ilich Ramírez Sánchez who took the moniker Carlos to hide himself when he plotted violence throughout much of the 1970’s, while 1962’s Harakiri and 1968’s Kuroneko are two Japanese films that delve into the rich traditions of Japanese cinema: the samurai film and the ghost story (respectively). All are presented in pristine condition by the Criterion collection on Blu-ray. Check out our reviews of Carlos, Harakiri and Kuroneko after the jump.

In Carlos, Edgar Ramirez plays the main character, and he’s on screen for almost the entirety of the film’s five and a half hour running time. The film starts as Carlos first becomes involved in terrorism in 1973 and he quickly moves to shooting – though not killing - a politician. He feels successful and the film sets up the terms of that success. Shortly thereafter he wanders around his apartment naked. It’s one of cinema’s most striking uses of male nudity - in that moment you can see how his prowess and ego are wrapped up in his success.

Assayas uses sexuality and the times to define the character. He hops from woman to woman as his rise in infamy begins. Of course, the incidents in which he’s involved rarely go according to plan. He helps the Japanese red army (who come across as mostly incompetent) by throwing grenades into occupied buildings, and attempts at using a rocket launcher to shoot airplanes goes comically wrong twice. But though many of the people he works with are fumblers, Carlos is a cold blooded killer at heart, and when he and a lover are investigated by the police when betrayed he wastes no time in killing the cops – who he gave drinks to moments before – when cornered.

Carlos’s biggest coup as a terrorist was kidnapping an Opec convention, and it’s the centerpiece of the film where the plotting and unraveling of their plans commence. They’re given a plane eventually, but once they’re in the air where they can land and how they can succeed with their political prisoners become questionable. Through this Carlos achieves his greatest fame, but is no longer as accepted by his movement for his decision-making (though jealousy also enters into it).

As his power beings to wane, Carlos settles down as much as he can with Magdalena Kopp (Nora von Waldstätten), but his later years are filled with a lot of ideas (and gun running), but little success. One of the film’s greatest strokes is showing Carlos teaching a class on terrorism as his star power has waned. The film concludes with his eventual arrest at the point in which he’s no longer much of a threat to anyone.

Though the film follows the structure of the gangster story – that of a man who rises to the top only to fall – what gives the film its weight is the length. Though there was a theatrical cut of the film, the longer version shows Carlos age over twenty years, and it achieves a great natural rhythm in the longer version. Ramirez puts himself and his body through the ringer as Carlos balloons up when he goes inactive. Ramirez’s work here is master-actor stuff; it’s a career performance. And though other films of this type show sharks who cannot stand not moving forward, here Assayas connects Carlos’s work to his sex drive, and that comment on masculinity gives the film great strength. Ramirez plays that perfectly. Though all the acts are political, the film frames everything as about power and fame and not ideology. Belief is mostly secondary, which is framed by the film’s soundtrack – mostly punk and new wave. For these guys it’s about being a rock star, and the women react to Carlos as a famous figure.

Assayas also gets a ground level “you are there” approach, and the time allows him to go into the minutia of the Opec kidnapping - you can see how the characters get into situations where they are completely out of their depths. Perhaps because of the length and the TV-miniseries structure, the film is broken into three sections, and the last section - where Carlos is becoming exceedingly irrelevant - is the hardest to watch (though they find good humor and details to make those sections pop). It’s still engaging, though I’m curious to see if it plays stronger if the film is broken up over three nights of watching, versus watching the whole thing in one setting (which I’ve done twice). It’s a great work, and was one of 2010’s best films.

The Criterion Collection Blu-ray presents the film over two discs, with the first two episodes on disc one, and the third on the second. The film is presented in widescreen (2.35:1) and in DTS-HD 5.1 master audio. The transfer is perfect – there are no flaws to note, and since the mini-series was conceived of in cinematic terms it looks and sounds great with rear channels in use. Disc one offers the film’s theatrical trailer, a documentary on the shooting of the Opec sequence (20 min.) and selected scene commentary by cinematographer Denis Lenoir on six scenes (9 min.) in English.

Disc two offers the rest of the supplements, and it’s a mother lode. There’s interviews with Olivier Assayas (43 min.), Edgar Ramirez (20 min.) and Denis Lenoir (13 min.) on the making of the film which are very insightful on to the working relationships and their process on making it. This is followed by the 1997 French television documentary “Carlos: Terrorist Without Borders” (59 min.). It’s followed by an interview with Hans Joachim Klein, who palled around with Carlos during the 70’s (39 min.). The set concludes with “Maison de France,” which covers a 1983 terrorist incident orchestrated by Carlos (89 min.). From this set you get a great sense of not only how the film was made, but some historical perspective. Or, to be more precise, exactly what one would want or hope for from a Criterion edition.

1962’s Harakiri is a truly gripping yarn. The film begins with a samurai Hanshiro Tsugumo (Tatsuya Nakadai) showing up at the home a feudal lord, hoping to use his home for the location of his hara-kiri (ritualized suicide). As the lord prepares the space, Hanshiro is told of Motome Chijiwa (Akira Ishihama) who came to kill himself and did so hoping to be given money to go away (a routine masterless samurais pulled often back then). Motome was then forced to commit hara-kiri with his sword, which – since he sold his real one – was made of bamboo. Hanshiro was told this to make sure he wasn’t wasting anyone’s time, but as he sits down to do it he asks for a second (the person who makes sure he finishes) who isn’t around. Such then leads him to tell the story of his life, and it turns out he has many secrets and a relationship with Motome that explains why he’s there.

What’s amazing about Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri is how it unfolds, and it does feel like a parchment revealing information bit by bit in the most exciting of fashions. Much of the action is told in flashbacks, cutting back to storyteller, building up to a samurai supposedly going to kill himself. As his narrative unfold it builds greater tension about the climax: Is he going to kill himself, or is this all an elaborate ruse, and then what is his plan? When the film concludes with Hanshiro taking on a whole house full of samurai, it’s one of those great action moments, made all the more awesome by it never feeling like he’s a superman.

And as revered as Akira Kurosawa is (and rightfully so) or how many have heard of Zatoichi, this is a master class samurai epic that is gripping from end to end. If you haven’t heard of this film, it’s worth running out and checking it out as soon as possible.

The Criterion Blu-ray presents the film in widescreen (2.35:1) and in DTS-HD 2.0 mono. The DVD release was a two disc set, and all the supplements are replicated here. The film comes with an introduction by Donald Richie (12 min.), and a 1993 interview with director Masaki Kobayashi (9 min.) that’s pretty boss. The section “A Golden Age” (14 min.) interviews star Tatsuya Nakadai and talks about his role in the film and his entire career. This is followed by “Masterless Samurai (13 min.) which interviews screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto. The set is rounded out with the film’s theatrical trailer.

Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko (translation: Black Cat) is a late 60’s ghost story, but it feels old fashioned - more drawn from the Val Lewton style ghost stories than anything approximating the R-rated sensibilities that would shortly grip horror. A period story, it too tells of samurai who find an out of the way estate where two women tend to the house. One is Yone (Nobuku Otawa) - a mother of a samurai - the other Shige (Kiwako Taichi) - the wife of a samurai - and both have long awaited the return of their kin to the home. But those who spend the night never leave, as the two are ghosts that made a deal with the devil to exact their revenge.

Once men begin disappearing, the local lord gets Hachi (Kichiemon Nakamura) to investigate. Hachi survived a heinous battle and has been made into the samurai Gintoki for his efforts, but the assignment he’s given is considered dangerous grunt work. When he comes to the house, he realizes that the two women are his mother and wife.

Moody and well shot, Kuroneko is a horror film that is, in its heart, a great tragedy. These women were killed a long time ago, and traded their souls for revenge – one of whom reneges on the deal once she comes in contact with Hachi – and so whichever side defeats the other, there is no winning. The film has a great sense of mystery, from the little subtle effects like a hair twitching like a cat’s to the severing of a hand that turns into a cat’s paw (cats are often shape-shifters in Japanese culture). Horror is made by mood, and the look and feel of this film is stronger than its third act, where the pieces must fall into place. But director Shindo was a great craftsman, and if this is the weakest of the three, it’s still a keeper.

The Criterion Collection Blu-ray presents the film in an excellent widescreen (2.35:1) transfer and in 2.0 DTS-HD mono. Extras include an interview with the director (60 min.) from 1998, thoughts from film critic Tadao Sato (17 min.) on the film and its director, and the film’s theatrical trailer.