We all know the economy crashed in 2008, but how many of us know why or how? Odds are, if you pulled a random stranger off the street they would struggle to properly define a recession, let alone explain the complex series of events that led to the economic crash – I certainly can't. In a world where economic theories and practices have come to rule of our personal lives (looking at you, credit scores) and dominate the sphere of political discourse, it's a bit unnerving when you realize just how little you actually know about what the economy is and how it works. Enter Morgan Spurlock and his production company Cinelan, who have partnered with numerous creative talents and economy experts to present We The Economy: 20 Films You Can't Afford to Miss, an ambitious short film series that explores complex issues like how human psychology causes recession, the struggle to define GDP, and the ins and outs of just what the hell the economy actually is. Livened up through performances, animation, dance, and varied cinematic approaches, the filmmakers behind We The Economy have found a way to make these often dull and confusing subjects accessible and entertaining to a wide audience.

In anticipation of the film series' release I recently joined a number of other journalists with Chris Henchy, director of GDP Smackdown, and his economic consultant Adam Davidson for a lengthy conversation that ranged from economic theory to wrestling lingo to animation technique. Check out what they had to say after the jump and click here to watch the short.

We know you guys had a lot free range on this can you talk about your process for sort of zoning in on one issue?

CHRIS HENCHY: It was kind of one of the topics that was on the list and I was kind of like, "I don't know, I don’t know." I have a degree in finance and these things kind of all go beyond me in a sense. I have a degree from a long time ago before computers. We had the HP 55, you remember those? Adam already had his topic and he said, "lets go out to dinner and see if there's anything that interests you with these." Then this Adam started talking about GDP with a passion and made it exciting and suspenseful. It was like a Tom Clancy novel. I was like, "And then what happened? You're kidding me!" And then we were just talking about like, how do you get that information out? Because it's very dry and not exciting information. I mean, as you start to scratch the surface – and that's what I think the intent of these films are. Here's a little bit of something if you're interested go read about it and it's a little bit more fascinating. It kind of is. It was the kind of thing where he made it seem very exciting and then McKay and I were talking and we had a couple ideas and he came up with wrestling and I was like, what a great venue or platform to get super dry information out from the mouths of wrestlers and then bring in the accountant and the economist and have those guys be the actual fighters. Once we started honing in on that it was exciting. Then there was a ll the information that McKay would send me to get into a script form that had some jokes that certainly seemed entertaining and then at the same time get all the stuff that you felt was important that we needed to get out.

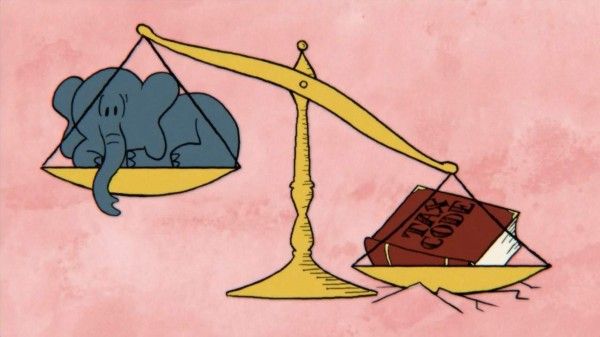

ADAM DAVIDSON: For me, that was one of the ones that nobody wanted – what is GDP? And that was one of the ones I wanted the most, because I feel like it is – I came into economics relatively late in life, but I've been doing it a while now, and GDP was one of those things that just seemed so boring. It's this number. What does it mean? I don't understand how that affects me. But there's actually a real drama behind it, there's real disagreement, it affects our lives in lots and lots of ways that we don't understand. So I had sort of the conceptual frame and I was able to tell them like, "So there were these two guys who had different views of what GDP should be in the '30s and they argued about it." [Laughs] Of course they didn't wrestle about it, they wrote boring academic papers about it and had chats at conferences. about it. So when they came up with the idea of making it wrestlers, it was so exciting. For me, that was the part that was so great.

HENCHY: I think we talked about this – what country is it that has a GDP definition that we go, "Oh, that’s a pretty accurate and all-inclusive and interesting way of looking at it"? Where would you say?

DAVIDSON: I mean there really isn't a best. The guy who we have in the film Simon Kuznets, who really is the father of the GDP, but then when he won the Nobel prize in the '70s his speech was like this bitter anti-GDP, "My child has morphed into this horrible thing," and the reason is – so, to an economist you want to measure the overall welfare of a country. How's the country doing? And some of the things that Kuznets thought needed to be included was the impact on the environment, the education, the freedom of women to find jobs, all these things that I think all of us intuitively -

HENCHY: He had these thoughts back in the '20s and all the way through there were environmental implications of having a healthy corporation come into a town and destroying the water - yeah, the corporation is doing great, but the town is now being run out and destroyed, but there's one building there, a monolith, that's making tremendous profits so the country's doing great. But that's not entirely the case.

DAVIDSON: There is a big movement right now, it's often called the Human Development Index, so the UN has numbers that bring in many of these other factors. So the UN can rank countries by the Human Development Index. Right now there's an interesting development where people are trying to rank it. The guy Meehan that we have [in the film], who created the current GDP system, his argument all along was that all that stuff's great, but you can't measure it. What I've got, I can measure it – how many cars Ford sold, how much lumber and steel, how much people are earning – I can measure it. How can I put a dollar value on an extra year of school for a twelve year old girl? So one thing that drove Kuznets crazy, and drives a lot of economists crazy, is like if a woman leaves work to raise her child that's bad for GDP, but it might be good for the country if she has that freedom. Alternatively, if a woman has to leave work to raise her kids, if there's no daycare or anything – GDP doesn't measure many of the things that we actually care about. So once you leave the median world of just corporate profits and economic activity, you enter a world of kind of arbitrary decisions.

HENCHY: I never knew about that until we sat down and had dinner, so now I look at GDP differently. I don't know if the definition will change in this country, but when I hear these numbers or you look at a company that's doing great you go, "Alright, what else is going on around it? Is it really as great as we hope and want it to be?" So that's a long, long answer to how we got drawn to it. It was that kind of discussion. Having dinner with Adam, which you should all do, and in fact I can start arranging those right now [laughs]. He said a great indicator of a country is cement.

DAVIDSON: Yeah, it's a huge thing.

HENCHY: Cement sales tell you about the health of a country. But then if you go to China where they put towns up, but there's no one living there.

DAVIDSON: Right.

Was animation the go-to choice for this?

HENCHY: It wasn't, but it was to try and figure out how to get an arena and get fifty thousand people in it. Adam McKay and I play basketball a couple times a week and he goes, "I got a solution that's going to make you really happy – animation." And I was like, "Uh huh." He was like, "I thought you'd be happier!" "What kind of animation?" Then we sat down and described the look that we wanted and they were like, "Oh yeah, we can do that." Then they did a quick little test using one of their guys and I was like, "Oh this is going to be really funny." Just really static-y aggressive moves. We were in our greenscreens at our studios at Funny or Die and what we would do is do a reading of it with each actor and just have them read, and then kind of based on how they read it – tone and whatnot – then we would tape them, put them on camera, and just have them do movements. "Give me an angry face". Then also go through and do all the mouth movements that we need. There's like ten of them that are all you need – an "A" an "S", the guys at the animation company know which ones they need. Then it was just making them do different moves, different faces and then they just kind of cobble it all together. I say it like that, like it takes a few minutes, but it takes hours.

DAVIDSON: It's syllable, by syllable.

HENCHY: Yeah.

And Rob Riggle, his performance is hyper-exaggerated. Was that your direction to go really over the top?

HENCHY: Yes, but that was also – I mean, Riggle's a great actor who has many shades, but hyper over the top is a good one. I was telling him, "Rob, what I'm thinking here is you're an announcer." He's like, "Yeah, I got it." "You're big, a lot of energy." He goes, "Yeah, I got it." "So I don't know if you want to walk around the loft for a few minutes to get into it." He's like, "I got it, shut the fuck up!" [Laughs] "I just want to make sure we're on the same page." Doing a bit with him the whole time. It's so clear what he's going to do.

How long did it take form conception to completion?

HENCHY: The production part of it?

Yeah.

HENCHY: It was really fast, maybe three weeks.

Who's the professional wrestling enthusiast? You guys nailed the lingo.

HENCHY: You know, it's just....if you see a little bit of it, you know what they're going to do. You throw phrases out there, stuff we do day to day anyway, but no I don't think I've ever paid on pay-per-view – I don’t think wrestling wants to hear this, but I've seen a little bit of wrestling. I went on YouTube and watched some. I just used the internet, I'd go on the internet and go "top five moves", so yeah.

It's not that complicated.

HENCHY: It's not. A little bit of surface knowledge goes a long way.

DAVIDSON: That, and the team of linguists you hired.

HENCHY: Yeah, I didn't have to put a room together [laughs].

Since the economy went south in 2008 the average person will complain about it, but they probably can't articulate what's wrong. Did you guys feel almost obligated as filmmakers to do this?

HENCHY: I think that some of the movies that we do, specifically The Other Guys and The Campaign, we try to write these fun comedies and then put a little story into it. The Other Guys came out I think in 2010 so it was after '08, and '08 almost put a lot of these movies away and we had to rethink some things. But before that, while we were writing it, we didn’t want the bad guy to be – it was after Madoff, it was after the banks imploded, and it was the kind of thing where we were like, "Does the guy who's kind of like The French Connection, he's bringing ten pounds of cocaine with a street value of ten million to the city, is that a bad guy anymore?" Yeah, he's a bad guy, but the company that's going to steal a pension worth 750 million is still not even considered a bad guy. It made us think, let's redefine the bad guy. You go back and watch The French Connection and he's bringing in a million dollars of cocaine, it's almost cute, in a Lincoln Continental. It's like, "Let him do it. It's kind of cool what he's doing." [Laughs] He took out the floorboards.

Adam, in your expert opinion, what would you say drives the economy? Is it consumer spending, investment, savings or all of the above?

DAVIDSON: Yeah, ultimately in any short term, consumer spending, especially in the US economy, is the main component of GDP. It's what drives the rest of the train. But long term you need to balance consumer spending with investment or else ten years from now we wont have anything to consume. So in China where – it's a bizarre thing to think from an American perspective – but they save too much, they invest too much, they don't consume enough. So ultimately China's growth has been driven by our consumption. We buy stuff that's made there, and we know that's an unhealthy thing, long term that can't sustain. Ultimately consumption is – and consumption is broad, it just means spending money on stuff, it doesn’t have to be physical goods, it can be services, but ultimately that's all the economy is about. So everything else is like kind of figuring out the time frame over which you can consume. So imagine let's just spend a year spending everything – spend it all, fire sale – and then next year we'd have nothing. So that's why investment and savings are important.

What's the biggest lie you think we've been told about the economy?

DAVIDSON: Honestly, for me, the biggest lie is that the people who talk about the economy like it's a science where people really know what they're talking about. I think economics has valuable tools and I like economics, but what I like about economics is that it allows you to think through problems creatively. It does help you understand, but it's not – just like with GDP – you hear about GDP and it sounds like this stable given, but beneath GDP there are all these assumptions, there are all these short hands, there are all these things that kind of prefer some groups over other groups and that’s the truth of all economics. It's not physics. When you weigh this [glass] you're actually weighing something that exists in the world. With economics you're not weighing anything, you're conceptualizing a tool, like GDP, for a purpose, but it has failings.

HENCHY: That gets into the whole world like credit default swaps and all these things that are just theories and formulas that billions of dollars are based on. It's air.

Like getting an 850 credit score, for example. Can anybody achieve that? The math behind that.

DAVIDSON: Right, and even the assumptions behind that and how it has this incredibly powerful impact on so many people's lives. The thing is, I think most economists know all this. If this was a room full of economists they'd all be like, "Yeah." It's the handful of economists who assert absolute certainty that become famous, so I think there's a distortion. But that was what was so cool for me about working with Chris and getting this done was that economists have been arguing about GDP for ninety years, it's not new, this has been going on, and pretty intensely, for ninety years and nobody else knows [laughs]. It's just this conversation that the eggheads have.

HENCHY: Yeah, it's this weird battle that has taken place that we all kind of are either rewarded or punished, I guess, by it. I don't know if that's the right choice of words.

DAVIDSON: Yeah.

HENCHY: But a lot of what happens on our day to day between what we buy, how we can buy things, the housing market, all these things are all based on these things and it's just because one person had an opinion that was stronger than somebody else's at the time. it's whoever is writing the history books gets to write history in a sense.

Chris, you mentioned that you try to include an undercurrent in your comedies that's a little more serious or weighty.

HENCHY: Yeah, a little something.

Is there anything about this experience that you learned or saw, or maybe your conversations with Adam, that will change how you write movies from now on? Or maybe has inspired a future film?

DAVIDSON: You told me you're doing a movie about me, is that not-?

HENCHY: [Laughs] It kind of reinforces stuff that we've done. A lot of that you pick up from Adam and Will, things that are important to those guys and important to myself, but that kind of help you write a comedy so they're not just a comedy. You're able to kind of hang the whole story on these little facts or stuff like that, about the economy or about politics, things like that. You try to – especially with The Campaign – we try to make it as nonpartisan, show both sides. If you can write a comedy where people go, "Oh, that's interesting." There's money in politics and if from both sides of the aisle you can look at it and go, "Yeah, maybe there is too much money in politics." Same thing with The Other Guys. It was Adam McKay's great idea with the credits just to show disparity in this country with wealth, what a CEO makes and what a worker makes. It's all out there. Its just - do people know or not? If people know and they're fine with it, then you've done your job. There's nothing you can do. If people go "I want to change it. I want to vote differently. At least I know what's going on." Then we're better for it.

Is this a different kind of fulfillment from when you make those other kinds of movies?

HENCHY: Yeah, it's interesting. I do get excited when people like a comedy and they think it's funny and quote jokes. At the same time I'm also happy that at least they watched something that hopefully had another level to it. I went to a party and somehow got cornered by twelve college guys who knew The Other Guys more than I did. I don’t think they realized what kind of comedy we were making [laughs], but they certainly had fun. Before they handed me the giant bottle of tequila they were yelling for Other Guys 2. It's funny because they were all quoting lines and their softball team was named "The Other Guys", but one guy did bring up the credits. It was like – Oh good, out of these twelve frat bros one of them walked away like, "The credits were like, eye-opening."

We The Economy is available now for free on more than fifty platforms, including Netflix, Hulu, and iTunes.