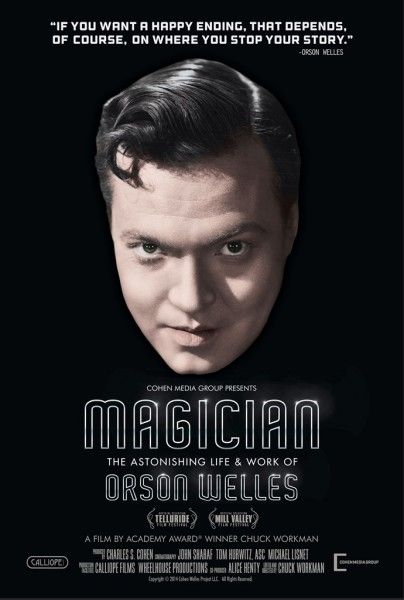

Academy Award-winning filmmaker Chuck Workman’s new documentary, Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles, takes a fascinating look at one of Hollywood’s most iconic figures. Welles’ remarkable life began as a musical prodigy at age 10, a director of Shakespeare at 14, a painter at 16, a star of stage and radio at 20, and a filmmaker at 25 with the groundbreaking Citizen Kane. Opening December 12th, Magician features scenes from almost every existing Welles film, clips from his television and commercial work, and detailed interviews with Welles, his family, and filmmakers including Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, Richard Linklater, and close personal friend Peter Bogdanovich.

I recently landed an exclusive interview with Workman whose documentary will be part of Woodstock, Illinois’ upcoming celebration marking Welles’ 100th birthday. He talked about what made Welles such a singular filmmaking talent, how he was an indie filmmaker working outside the system in an era when there was no independent film, the challenge of shaping the film without destroying its integrity, how what’s often considered Welles’ greatest masterpiece was also the first film he ever directed, Welles’ progression as an artist with each film, his unfinished projects, his legacy, and Workman’s next projects. Check out our interview after the jump.

How did this first emerge? What inspired you to make a film about Orson Welles?

CHUCK WORKMAN: I think he’s an incredibly important filmmaker, and maybe I feel that as an outsider and an insider also, because even though I worked totally in Hollywood commercial work, it wasn’t totally though. I worked in it, and I made a living out of it, and I raised a family on it. I still felt a little bit of an outsider. I felt like I guess Saul Bass might have felt, or somebody like that, where you were there in the middle. You were kind of the person that they would call every once and a while. Gil Cates treated me like that frankly in his wonderful way. I was like this crazy guy. He knew he had this guy in the corner that he could call up and I would do whatever he wanted. I knew him really well. We shared an office at one time. Putting me into those Oscars one after the other and getting behind me, even though I had already proved myself to some extent, that took a lot of courage. He was great. (Gil Cates produced the Academy Awards telecast a record 14 times between 1990 and 2008. Workman created short films and openings for twenty Academy Awards presentations and two Emmy Award shows, was nominated for an Emmy for Directorial Achievement for his work on the Oscar show, and has been nominated nine times for editing on the Oscar show.)

How much did this project change from inception to final film? Is it pretty much what you set out to do?

WORKMAN: Yes, I think it is. I had a script. I always write a script or a treatment anyway, 12 pages or so. I’m looking for an action in the film. I’m looking for something that is driving the film, me driving the character, whatever it would be. And I found that. It’s hard to articulate but it’s there in the film. It’s Orson Welles trying to stand out in a way, and knowing he can, and trying to do what he wanted to do, and knowing he could. That’s another problem, you know. So, structurally it’s more or less the way it was. There was a certain amount of editing that I did as I was editing where I’d say, “Okay, this scene should be here and that one should be there.” But basically, I’m following chronology. I’d never done a film that bang, went right into, “I was born…” but saying, “I was born” is what was in my mind. I’m thinking of David Copperfield, which started that way. When you read a biography, sometimes that first chapter where they talk about the parents and they grew up here, and they’re from an Irish family or whatever is the boring part. But he had such an interesting early life that I knew that wouldn’t be boring. So, I wasn’t afraid to just jump right in.

What do you think made Orson Welles’ vision so unique and distinguished him from other filmmakers?

WORKMAN: That he’s an artist. I don’t think he did this consciously, but he was looking at cinema as art in the same way that he would direct Macbeth or adapt a Dostoevsky story for radio. He felt that this was all part of an artfulness that was part of his life that started when he was 8 years old or before. I don’t know if William Wellman who was a pilot had the same experience, or John Ford. I think that those people making films in those days were not necessarily interested in that. Maybe John Huston was. So that was one thing that distinguished him, and I think his goals were different, that he didn’t want to just keep the job. He did want to keep the job, but it wasn’t like he was just trying to do some piece of mass entertainment and then go to Europe and take some time off. This was really an art form that he felt was very important, and he wanted to work in it the way he worked in theater, the way he worked in radio even, the way he wrote when he wrote things. He wrote about Shakespeare, for instance. The Hollywood world for him was like the acting world he did. It was like Jane Eyre. It was like romantic nonsense in a way where you can make some money. So, I think that was one of his problems, and why he didn’t fit in was because he didn’t see it as that. He kind of dismissed it.

I remember when I first started working on the Oscars, there was a very serious woman who had made a documentary about some political subject, and she said, “It’s almost bad for me to win the Oscar.” She felt that this was some frivolous world. I don’t know if he felt like that, but what certainly came out was that he wanted to be nice to the people that were paying for him, and he wanted to do it well, but he still wanted to be Orson Welles. He was already a star before he got to Hollywood. James Naremore said that he was a bigger star in 1938 than Hitler was. He was more well-known than Hitler at the time. I don’t know why… I shouldn’t have taken it out, but for some reason I cut that line and I didn’t use it. So, here he is, he’s the master bringing his own ship through the canal and it’s suddenly a different world. He’s not in that world anymore. He’s in a world where the goals are different, and so he ended up sometimes on the shoals.

Richard Linklater called Welles the patron saint of indie filmmakers. Was he too audacious for Hollywood or was he simply misunderstood?

WORKMAN: In the past 20 or 30 years, you could be an independent filmmaker even in Hollywood. You could raise your own money. After you were finished, you could go to Sundance and show the film. Every year there’s something else. Now you can go online and find money. So, there were always ways to do that – to find money or to put your own money into things – but that was not done in 1942 or 1948 or 1955 or 1965 very much. He was an independent filmmaker when there was no independent film. He wanted to just have somebody put up the money, like they would in the theater, and he’d put on the show. Thank you very much. And that wasn’t happening in Hollywood. They had a different agenda than him. When he clashed with them, I think it was because there was a streak of him that just didn’t understand that, another streak that wouldn’t and didn’t want to understand that, but also, there was a stubbornness. “Hey, I’m Orson Welles. This works for me. I know I’m only 25 years old, but this seems to work.” I think that hurt him and caused him to say after a while, “Okay, I’ll do what they want. If it works, fine. If it doesn’t work, let them finish, whatever they want to do.” It’s being superficial and glib to put it that way, but in a way, that was what he was like.

What I find fascinating is that the first film he ever made was Citizen Kane, which became so iconic, and yet he says in your film, “I didn’t know how to make a film. It just seemed that would be the way you would do it. So that’s what I did.”

WORKMAN: And then what happened was the next 10 films or 11 films or 15 films, because some of them weren’t finished, he did know. He did learn how to do it, because with each film, he would learn something. He learned a lot about photography in the first film with Gregg Toland (cinematographer on Citizen Kane). He was not a photographer. He was a stage guy. Suddenly, he learns all about photography and how to shoot a scene and how to light a scene, so that you see this amazingly rich photography in The Magnificent Ambersons, his second film, where Stanley Cortez is now the cameraman. Gregg Toland wasn’t available. You see a progression, and then you see a progression in editing later on, and you see a progression in the way he uses actors. He wasn’t using himself so much. He was using other actors. He made certain mistakes probably in casting in Ambersons, so he learned, “Okay, I’m not going to do that anymore. I’m going to do it my way.” So, when he couldn’t get Agnes Moorehead for The Stranger, he got Edward G. Robinson, and that was not the same at all. Also, they cut a reel out of The Stranger. That was his third film when he was trying to really make a Hollywood film. That didn’t work either.

What did you find was the most difficult aspect of making this documentary?

WORKMAN: There was just so much to get to and to work my way through. It wasn’t physical. It wasn’t like there was a lot of physical material. That, I’m used to. It was just trying to get my head around how to make a movie out of it, rather than just compile it, one thing after another. I was trying constantly to work it into [a story]. A documentary is hard enough. It has no story. So, if you have a documentary with this kind of chronology, it could be a very straightforward biography. Or it could be something that’s got its own drama to it. And that’s what I was trying to do. It was to bring something to it without destroying its own integrity, so that it was true to the Welles story and to what I was trying to say about it, but at the same time had a shape. And that, to me, was something that I was constantly worried about in making the film.

What was the biggest surprise or discovery you made about Welles in the process?

WORKMAN: It was how he progressed from film to film and how strong his films were at the end, even though a lot of them were generic pieces. Even Touch of Evil, in a way you can look at it as a film noir and most people do, frankly. He would just move along. Everything that we do, what you do or what I do, people think, “Oh, you did it the same way 10 years ago, 15 years ago, as you do it now.” But you don’t. You’ve learned after those years. You learn how to change and how to do your job, whatever it is. He learned in the films, so that the later films are very, very rich. I learned a lot about that. I also learned about all these unfinished films. I didn’t know he had so many. That was encouraging because I have a lot of unfinished things. Everybody does as they pointed out. So that part, to me, was very interesting, that all these films were floating around.

I was always aware he had unfinished films that were in various stages of progress, but I never realized how many until I saw your documentary. What do you think that says about him?

WORKMAN: For one thing, it says that he’s working outside the system. The system would not let him do that, because there’s interest to pay on those films, and there are release dates. It’s not like when you go and you paint a picture. Picasso put his pictures that didn’t sell right away against the wall and let them sit, and then they became the most important paintings ever made in the 20th century after a while. But Welles couldn’t do that. Normally, a filmmaker was not supposed to do that. You’re supposed to turn it out. I had a friend, a documentary filmmaker, who said, “If you can’t make a film in three months, and get it out in six months, you’re wasting your time and you shouldn’t make the film.” I said, “That’s the opposite of what I think. It should take four years if you need four years.” If the funders are patient, you should do that. If it was a good idea in the beginning, it’s worth going into. So, that’s what he did. He was trying to figure out the movie. You know Philip Roth has a great line about when he starts a book. He said, “What do I have to do? I have to solve the problem of the novel.” In other words, he has an idea, but he doesn’t know exactly how he’s going to do it. I don’t know it either frankly. You need the time to go through your process. And so, that’s what Welles did, and sometimes he just didn’t finish.

How was your experience going to Woodstock, Illinois to visit the Todd School for Boys that Welles attended and filming inside the theater where he made his American debut as a professional theater director and put on his first Shakespearean productions?

WORKMAN: That was fun. It was one of the things I was trying to do for the film. I wanted to try and get a look at what is happening today with Orson Welles, and the tremendous importance to him of this school -- and he admits it in interviews -- and what was going on there now. I found out they still have a society. They revere him. There was this coincidence of the Woodstock Opera House Stage being named [in his honor], and I thought okay, I’ll go shoot there. That’s where I found his classmate, the 90-something-year-old woman you see in the film. She was very nice. She lives near Woodstock, too. We went out and we shot that. We had a couple days in Chicago where we did a lot of stuff. It was a good experience, and I wanted it in the snow. I kept saying, “I’m going to come in February. Is it going to snow?” I wanted it to snow because it would be like…

Rosebud?

WORKMAN: (Laughs) Rosebud! Exactly! It just felt right that it should be in the snow. And it was a rainy snow, but it was snowy enough that I got some of it in there. That’s where they shot Groundhog Day, that city.

When I saw the beautiful snowy setting, I immediately thought of Citizen Kane.

WORKMAN: Exactly. Well, I was trying to do that. They’re having a 100th Birthday Party there for him in May and they’re going to show this film. I’m going to go.

Of all his films, what’s your personal favorite?

WORKMAN: I always thought Citizen Kane was my personal favorite. People would say, “What’s your favorite?” and I’d say, “Oh, it’s Citizen Kane.” It’s amazing. But as I’m working on the film, I see these later films. There’s Falstaff and F for Fake. I’m an editor, and F for Fake is a flamboyant editing piece. I like The Trial. Peter Bogdanovich claims that he didn’t like The Trial and neither did Orson. But then, Orson came around and said he liked The Trial and he invited Bogdanovich to a screening. He said, “Come to a screening of a film that I know you don’t like.” And that was The Trial. When I look at The Trial, I think it’s just terrific. It’s very amazing. Each film seems to have something, even the lower end like Mr. Arkadin and that sort of thing. I like Touch of Evil also. It’s an extraordinary film.

I love Touch of Evil. That’s my personal favorite with that amazing opening shot.

WORKMAN: Yeah, and people laughed at Touch of Evil. My lawyer, when I started the film, he said, “Oh, you mean that fat guy who was in Touch of Evil? That’s what you’re going to do a film about?” And I said, “Yeah.”

What do you think is going to become of The Other Side of the Wind and Welles’ other unfinished films like Don Quixote and The Deep?

WORKMAN: The official story is that it is being recut, and all the rights are resolved, and it will come out in May. I know Peter Bogdanovich is working on it. I know Frank Marshall is working on it. Those are two very reliable guys, and I think they’ve worked out the problems of who owns what. So, let’s hope that it will. That’s one of the few films, and it may be the only one, where you could say that Welles left enough of the film and enough script and enough instructions that you can put it together the way he wanted. And certainly, with Peter and Frank Marshall, they’re Wellesians in their way. They both worked on The Other Side of the Wind so they would follow the instructions. They wouldn’t try and say, “Oh, we’ll make it our way.” They’re going to try and make it his way. I’m hopeful that that will be finished properly and will come out. I think it probably will.

Some of the other unfinished films may just never happen. There wasn’t enough of them shot or they’ve already been mangled. Don Quixote, which was a big project for him, was sold off to some Spanish group, and they added all these other scenes, and they kind of messed it up. That one was also close to being finished and isn’t finished. Some of them require a voiceover, a recut, or some other scenes that Welles would have done. There’s no question that Welles worked that way towards the end of his life. He would just look at something and say, “I’ve got to do a scene. Let me call my cameraman up.” He’d say, “I need a shot where I can say this.” And he would do it. He would shoot the shot. You can see that all over F for Fake. They might have needed that and he didn’t have that. Some of them needed dubbing where the people got a little too old to dub the lines. Jeanne Moreau, for instance, never dubbed her own lines in one of the films. And people died. Laurence Harvey died before he finished his film. They were both on The Deep. They just don’t happen. It’s like these people that leave novels and they’re interesting. I mean, it’s interesting to look at them, but they’re not real films.

How was it working with Orson Welles’ family?

WORKMAN: The family is careful. His eldest daughter (Christopher Welles Feder) is really nice. She’s a woman who lives in New York City. Her husband was a teacher, the kind of teacher that would come home with papers to correct every night. She also worked in academia somewhere. She was involved in some sort of children’s puzzle that was popular. Anyway, she was very nice. She wrote a very good book about her and her father called In My Father’s Shadow: A Daughter Remembers Orson Welles, and I would recommend it. She talks about the ambivalence of having a celebrity father like him as a very charming, big figure in her life and being this daughter who wanted to be a good daughter and at the same time wanted to have her own life. That was tricky for her. She lives with all that. She’s about 75 now.

There’s a younger daughter (Beatrice Welles) who didn’t want to participate in the film unless she could have some idea of what we were doing in the film. It was more than that she wanted. They wanted me to “present the film to them,” meaning I would pitch the film to them and they would decide. I didn’t want to do that. They could say they didn’t want to do an interview and I would understand that. So, we didn’t do much with the younger daughter. I found some stock footage where she’s talking about Othello (Orson Welles’ 1952 film which he directed and produced and also played the title role). That was all.

And then, there was a middle daughter. He said he had three daughters like King Lear. There was a middle daughter (Rebecca Welles Manning) who died and that was Rita Hayworth’s daughter.

And then, there was Oja Kodar, the girlfriend for the last 20 years of his life who he lived with while his wife and daughter lived in Las Vegas mostly and also Sedona. He was living right off Hollywood Blvd. with Oja most of the time. She was very cautious. She really protects his reputation and is very careful. She’s totally sincere, I think. She’s 73 now. She finally consented to an interview after a lot of back and forth. I went to Croatia and we shot it there.

How does the final film compare to what you originally envisioned?

WORKMAN: It’s a richer film than I thought it would be. I mean, I always have high ambitions. I knew it was an important subject. I didn’t realize how important a subject it was frankly. I thought, well I’m a film buff. I’ve worked in film my whole life. Of course, everybody is going to know who Orson Welles is and why it’s important. But I didn’t realize how significant it would be, especially with this 100th birthday. I thought I’d be done last year so I never thought I’d be this close. I had extra time and I think the film for me is as good as other films I’ve done that I’m really proud of. I did a film on Andy Warhol called Superstar that I liked very much. I did a film on The Beats called The Source that I liked very much. And this one I think compares with that. So I have that, and my friends tell me, “Oh, it’s your best film.” Okay, fine. It came out the way it came out. A lot of it is subject matter when you do a documentary.

What would you say is Orson Welles’ legacy?

WORKMAN: He’s one of the greatest artists of an art form that has no canon yet. So he is part of the canon in a way. His work is something that we can look at and remember the days when Gone with the Wind was the greatest movie ever made. Things move on, but I think that’s his legacy. It’s a touchstone of great cinema.

What are you working on next?

WORKMAN: Over the past five years or so, I’ve been playing with experimental narrative and shorts and things like that. I have a feature that’s not necessarily mainline narrative, but is a little off and for me a little more interesting. So I hope I can get to do that. It could be that I get called to do another job. We’ll see.