[This is a re-post of my review from the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival. Cloud Atlas opens today.]

"My life exists far beyond the limitations of me," a character notes in Cloud Atlas. By the same token, The Wachowski Siblings and Tom Tykwer's film exists far beyond the limitations of genre, narrative, identity, and time. It is a work of sweeping ambition, engrossing stories, compelling characters, and powerful emotions. The filmmakers have taken David Mitchell's novel, and rebuilt it into a captivating sextuplet filled with love, hate, redemption, damnation, bravery, cowardice, and more. Through skillful editing and astounding performances, Cloud Atlas is a cinematic experience like few others, and it will leave viewers in awe.

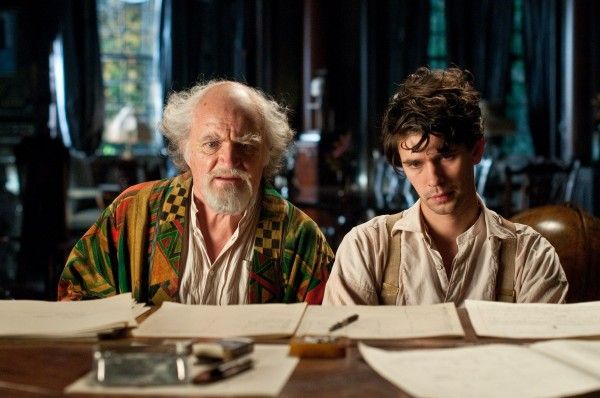

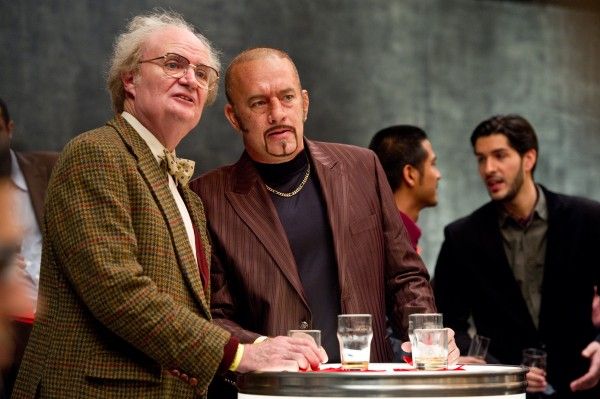

Cloud Atlas spans across six stories in six different time periods with the lead cast playing different characters in most or all of the narratives (I will use the names of the corresponding stories from the novel to make it easier to differentiate the tales later in the review) The six stories are: the voyage of Adam Ewing (Jim Sturgess) across the Pacific Islands in 1849 [The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing]; the relationship between amanuensis Robert Frobisher (Ben Whishaw) and composer Vyvyan Ayrs (Jim Broadbent) in 1936 Europe [Letters from Zedelghem]; reporter Luisa Rey's (Halle Berry) dangerous investigation into a nuclear power plant in 1973 San Fransisco [Half-Lives: A Luisa Rey Mystery]; the constant, but perhaps deserving, misfortunes of vanity publisher Timothy Cavendish (Broadbent) in 2012 England [The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish]; the fabricant Sonmi~451 (Doona Bae) and human Hae-Joo Im's (Sturgess) action-packed escape from authoritarian forces in 2144 Neo Seoul [An Orison of Sonmi~451]; and Zachry's (Tom Hanks) perilous journey with the mysterious Meronym (Berry) in Big Isle, "106 Winters after The Fall" [Sloosha's Crossin' an' Ev'rythin' After].

The movie opens with Old Zachry beginning a tale in front of an unknown audience, and then the filmmakers provide the opening scenes to the above stories in chronological order [To be precise, Tykwer directed Adam Ewing, Luisa Rey, and Cavendish while the Wachowskis handled Zedelghem, Sonmi~451, and Sloosha's Crossin']. From there, the film cuts between the narratives usually through visual rhyming, a shared moment (like a character entering a room in one story, and a character exiting a room in another story), or an actor who's playing two different roles (like cutting from Luisa Rey to Meronym). It sounds complicated, but the connections tend to flow elegantly, although it can be a bit distracting if there's no connective tissue. But these are minor bumps that are quickly forgotten as we're enraptured by the latest plot development in each tale.

And they're all terrific stories. In terms of their narrative breadth, they're relatively narrow. They're basically short films contained to a particular genre. There are two period pieces (Ewing and Zedelghem), a pulpy thriller (Luisa Rey), a comedy (Cavendish), and two sci-fi yarns (Sonmi and Sloosha's). Like all good adaptations, the filmmakers have streamlined the plots from the book, and come away with propulsive narratives that never lose their momentum. Anthology movies are almost always a mixed bag, but Cloud Atlas is the exception to the rule. The Luisa Rey story is a tad weaker than the others because it lacks an emotional arc, but there's not a single plotline where we check our watches and wait to go back to a story where care about.

Even if there was such a plotline, it would swiftly fade. The sweeping pace of Cloud Atlas is perfectly timed down to the second. Editors Alexander Berner and Claus Wehlisch have worked a miracle, and used cinema's unique quality—the edit—to its full potential. The film positively sings as it moves between stories and crescendos at narration that breaks the bounds of time and space. It is the most crucial element in the film's central theme of how we are all tied together through our actions and our fates.

Notions such as past lives and intertwined destinies can come off as hokey, and if they're to be explored, then the artist (or artists, as the case is here) must leap with complete abandon and total confidence. There is no half-measure in a film of this size, and the filmmakers' wholehearted commitment is why Cloud Atlas manages to transcend new-age notions that would be worthy of derision. Furthermore, such a reading is far too literal and misses the point shared by each story; a point perfectly summed up by one of the characters: "our lives are not our own." It is not simply a matter of the individual repeating throughout time. It is how he or she treats others.

Distilled into their basic element, each actor's major characters share a single defining trait. Hugo Weaving's characters are sadistic, Berry's characters are inquisitive, Sturgess' characters help the enslaved, etc. But not everyone is locked into a single trait throughout lifetimes. Before Cavendish, Broadbent's characters are selfish. It isn't until his experiences in Ghastly Ordeal that he is finally able to change. This isn't a matter of karma. It's a matter of giving to others rather than taking for one's own survival. Broadbent's overarching character makes this change in one story, but it's what Hanks' characters wrestle with over the course of the entire film. His characters move though thieves, liars, cowards, and finally to someone who must resist a devil that's followed him throughout time. Hanks' characters are not the center of the universe nor are anyone else's. None of these characters are giants of history. They simply continue to criss-cross across not only time and space, but also race and gender.

Cloud Atlas is greater than the sum of its parts, and its parts are stunning. Cavendish is hilarious, Sonmi is pulse-pounding, Zedelghem is melancholy, Ewing is treacherous, Luisa Rey is exciting, and Sloosha's Crossin' is something else entirely. Sloosha's Crossin' was my least favorite story in the book due to its unbroken length and the difficulty of reading through a slang-filled dialect. But in the film, it works marvelously and becomes a beautiful, unforgettable tale where we happily accept characters who call technology "smart" and call truth "true-true". Translating the story directly to film and leaving this bizarre dialect intact requires a glorious mixture of fearlessness, insanity, and unbound imagination.

This kind of imagination—to transcend genres, settings, and identities—requires a certain kind of genius. Lana Wachowski, Andy Wachowski, and Tom Tykwer have shown that genius with Cloud Atlas. It is an ambition rarely seen in modern cinema, and rarely realized due to budget constraints (the film was independently financed). The audacious, daring vision of Cloud Atlas is to be cherished because it pushes the bounds of what we've come to expect from movies. It is a forceful reminder of cinema's power, and why it stands apart from other art forms.

For all the complexity of its editing, its actors with multiple characters, and the jumps between genres and setting, Cloud Atlas is beautifully simple in its central theme. The characters narrate their philosophies, but it doesn't come across as moralistic. All of the characters are writers. They use different forms, but they're all narrating their lives. They're looking inwards to create connections, and in so doing, forge a legacy. They leave behind more than they were in a single lifetime. Even if their messages are misunderstood or reinterpreted, the authors' bold, declarative words still echo through the lives of others across time and space. Through the gorgeous, life-affirming lens of Cloud Atlas, our lives exist far beyond our limitations.

Rating: A