A frequent theme in the oeuvre of writer-director David Cronenberg is how we become alienated through the ubiquitous. We fail to notice how everyday facets of our lives are changing us on a fundamental level, and causing us to be alienated from ourselves and each other physically, mentally, and emotionally. In Videodrome, Crash, and eXistenZ, Cronenberg explored how technology warped our relationship to the world to the point where technology became organic and the organic became mechanical. In his last movie, A Dangerous Method, Cronenberg explored how psychotherapy causes people to become distanced from their emotions and psyches. In his latest film, Cosmopolis, Cronenberg turns his eye to capitalism, and has created a darkly comic, coldly calculating look at a world where everything is for sale and nothing has value. Like A Dangerous Method, Cosmopolis suffers from the lack of an emotional impact, which is the inevitable result of a story where characters have become disconnected from emotion, but the story will still leave your head spinning.

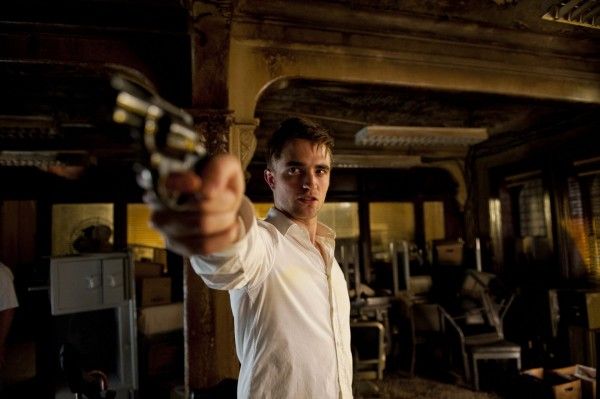

Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson) is going for a haircut. It's an innocuous errand except Packer is the billionaire head of a financial institution he inherited from his father. Packer has maintained his wealth the same way many modern financial titans do: he moves around numbers. But today, he has moved the wrong numbers, bet on the Yuan, and his money is disappearing by the millions. But this doesn't faze Packer, and nothing really does. And as he rides in his limo towards his haircut, he has casual, emotionally vacant conversations with various acquaintances. He can only really be bothered to exit his posh vehicle to converse with his wealthy new bride, Elise (Sarah Gadon), and their marriage is just another empty transaction that continues to decline in value. Meanwhile, the rat becomes a symbol of economic protest, and an unknown assassin is trying to kill him.

Cosmopolis is able to maintain its dry conversations because the raving lunacy isn't in the dialogue. The madness is outside the limousine. It's in a diner where two men can enter, hold up two dead rats a piece, and loudly chant, "A spectre is haunting the world!" before tossing the dead vermin at the restaurant's patrons. But that kind of bizarre behavior is nothing compared with how Eric and his cohorts view the world. In his limo, Eric undergoes his daily doctor's examine, not because he's sick, but because he wants it. And while receiving a proctologic exam, he carries on a conversation with an associate. Neither seems to mind Eric's doctor being elbow-deep in his patient's anus.

It would be inaccurate to call Eric and his various acquaintances "robotic." These characters speak in allegory, symbols, double-speak. They cling to the last vestiges of what humanity, but they no longer understand it. It's like a dead language without the romanticism. The reaction is similar to how characters behave in Videodrome and eXistenZ except the alienation in those movies is represented in organic videocassettes and game controllers. In Cosmopolis, the alienation is represented in the characters' souls in a world where everything is nothing more than a price tag. At one point, Eric inquires about purchasing a cathedral so he can put it in his home. He no longer understands that religion is for the masses or that it's meant for spirituality. It's something to be possessed and nothing more.

And what do you get for the man who has everything? You get him nothing, or rather, you get him to lose everything. Cronenberg has always been interested in following his themes to their disturbing conclusions, and in Cosmopolis, the world reaches the point where the numbers blur together and it all becomes meaningless. It's not simply "money can't buy you happiness." Money can't buy you sadness, anger, or any emotion.

Cronenberg has crafted a richly layered examination of capitalism where the broad themes will be apparent to everyone: the Occupy-like protests, the man in his limo who can't be bothered by the outside world, etc. And then you can dig deeper into the larger symbols, the broader societal commentary, and intellectually engage with a movie that provides no easy answers, but is meant to provoke discussion in a meaningful way. There's no half-hearted grasp at exploring our turbulent economic times with regards to the power of Wall Street. The movie is based off Don DeLillo's novel, which was published in 2003 and takes place in 2000, but Cronenberg's film is born out of 2008 crash and has no time period. The movie is timeless yet it functions as historical document.

It also functions as a superb meta-commentary on the value of celebrity by casting Pattinson in the lead. There could be no better choice, because not only does Pattinson break free of his romantic-lead mold, but by the very fact that we note his freedom. Robert Pattinson is a commodity. He first gained value by getting cast in Twilight, he has maintained his value by appearing in other romance films like Remember Me and Water for Elephants, and Cosmopolis is a calculated 180 for the actor. It's the only way his career continues to grow, and it's the smart move because he has attached his value to an indie feature, and split his risk by having David Cronenberg at the helm. Pattinson gives an intentionally stilted performance, but no one will be able to walk away from this movie thinking he can't act. He acts to the piece, and we'll have to wait for another role to "test" him.

This is how we measure a person. One could argue that we're valuing his talent and not him, but he carries the Twilight franchise with him. The industry will write about this move, his fans will decide if they want to see him in a role that couldn't be further away from Edward Cullen. Is Pattinson trying to lose everything like Packer? Of course not, but he also shares his character's desire for freedom. I can only imagine the feelings of a Pattinson fangirl who sneaks into the movie only to see her on-screen crush engage in act after act of meaningless sex. Hopefully, it will drive her to see Cronenberg's other movies and observe that sex is always a primal force rather than an expression of love.

There's no room for love in this world, nor any other emotion, which is what leaves Cosmopolis cold like A Dangerous Method. It's built that way, and the movie isn't dull because it's perfectly built, and Cronenberg has installed dark humor and comically bizarre dialogue like Eric telling his new bride, "You have your mother's breasts," and neither remarking on the strangeness of such a comment. However, the intellectual explorations of Cosmopolis shouldn't put up a wall between the audience's feelings for the characters or at least feeling some emotional resonance with the world Cronenberg is depicting. We can laugh at its strangeness, but it's tough to be pulled into its drama. We can react to what we're seeing, but we can't feel it.

Cronenberg can't be criticized for putting us right where he wants us, and where he wants us is to think about the alienation our economic collapse has caused. There's no attempt to make us pity Packer or his financially obsessed ilk. There's no room for pity in his movies about alienation. If anything, we're meant to marvel at the grotesque so that we can't ignore the issue it presents. The problem is that emotions drive us as much as our intellect if not more. Cosmopolis has the power to entertain and to enlighten, but it fails to recognize that we're not dead inside like Eric Packer. Not yet, anyway.

Rating: 8.4 out of 10