Ostensibly, the open-world video game aims to give the player as much freedom and control as a video game can offer. And in many key examples, in many wide-varying subgenres — from Grand Theft Auto to Breath of the Wild to Witcher 3 — this hypothesis is proven correct, submerging the player into a transformative, all-encompassing world where they truly can make deeper and wider decisions than in their “on rails” brethren. However, one giant, highly anticipated, and highly controversial recent release lays bare the seemingly paradoxical limitations of the open-world video game form; the loss of depth that occurs when you try to go as wide as possible. And it’s particularly ironic given that it comes from a studio that gave us Witcher 3.

Everyone’s dunking on Cyberpunk 2077, for a reasonable reason. Thanks to a toxic, crunch-filled work environment and corporate need to both make a financial splash in Q4 and satiate their vocal fanbase after years of anticipation and delay, Cyberpunk 2077 has come out unfinished. CD Projekt Red’s work plays with a shockingly pervasive amount of bugs, surreal glitches, game-breaking hiccups, and straight-up software crashes. I’m playing the game on a PlayStation 5, and literally every single play session has ended because the game has crashed on me; by all accounts, experiences on current-gen consoles like the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One are even worse. We’re all now unwitting, unpaid quality control playtesters, being foisted upon these bugs, comparing notes with each other online, telling CD Projekt Red what elements they need to fix about the game despite the game already being out. It’s been such a boondoggle that CD Projekt Red refused to give sites like us access to console versions until after the release, and is now offering consumers apologies and refunds. All of this is, again, particularly ironic given that the game itself tries to be about the corroding of experimental technology and the destructive nature of corporations being given free rein.

But when I can actually play the game, it is undeniably compelling… to a point. Well, more like a giant wall that the game’s design itself slams into over and over again. Cyberpunk 2077 is lucky that I came in loving the cyberpunk genre, as I am more than willing to tolerate its shallow engagement with that genre’s rich world. Like the characters trading around copies of copies of insertable shards, underground-manufactured tech, and trippy pieces of visual engagement, Cyberpunk 2077 only seems interested in wearing how pop culture has copied, re-manufactured, and tripped up “cyberpunk” as a set of aesthetics rather than a gateway to a slew of topics worth exploring.

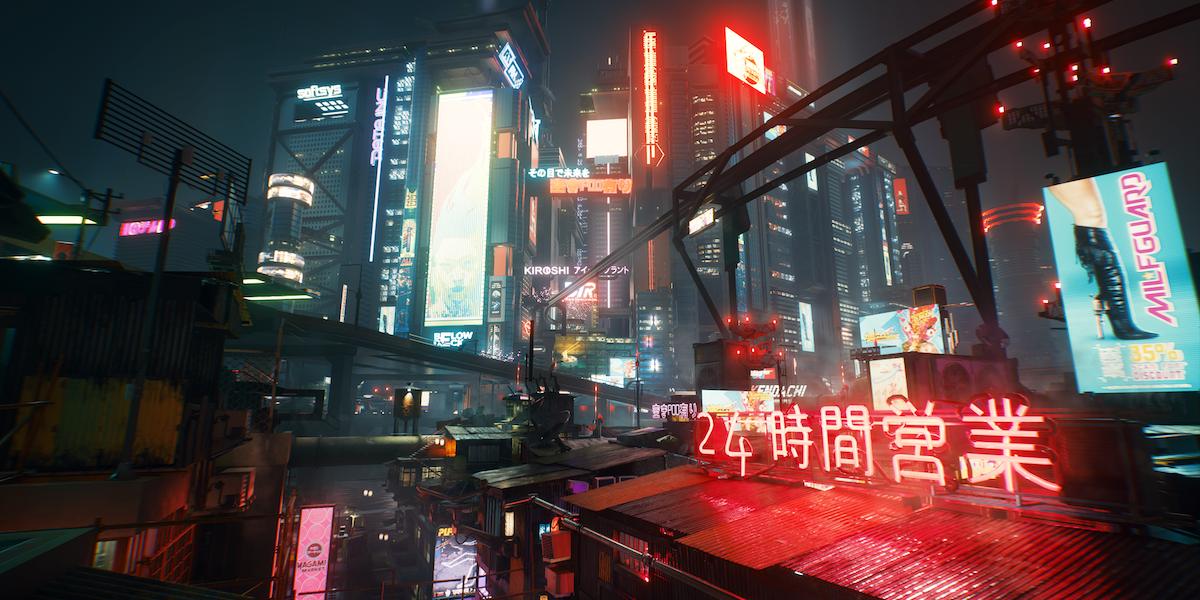

There are bleary neon lights, there’s a giant mega-city with oddly colored skies, there’s crime on every corner, there’s a wonky way of language crossing pervasive cusses with technobabble slang and hardboiled detective posturing, there’s a fusion of, and problematic obsession with, “Japanese culture” in every facet, there’s an icky fascination with the commodification of the female body, there are future people wearing future clothes with future cybernetic implants, and there’s lots of talk about corporations. All of this brings to mind our ethereal — well, let’s call it “cloud-based” -- pop culture data set of influential cyberpunk material like the Blade Runners, Akira, Hackers, The Matrix and Johnny Mnemonic (down to casting Keanu Reeves), and, like, the Kanye West “Stronger” video. But by trying to open up its aesthetic and genre worlds as widely as possible, instead of choosing one avenue to burrow deep into, it feels merely like a patchwork quilt of a postmodern stew; a cursory glance of the “cyberpunk Wikipedia” personified into a video game; an open world whose openness shuts me down.

Now, do I like blasting or slicing or hacking my way through a group of cyber-psychos with a smart-gun or katana or cybernetic implant as synth-pop blares at me? Of course I do, I’m only human (for now). But I don’t love it. If it had committed itself to only these junk food pop culture “chintzy on purpose” pleasures (like, say, DOOM Eternal), perhaps I would’ve grown to love it. But Cyberpunk 2077 is trying to say more beyond what we see on the surface; it’s just saying it all so superficially, constantly getting marble-mouthed in its desire to be so open, so encompassing, so “everything.”

It has the desire to talk about society’s descent into a technocratic corporate-controlled dystopia, the ever-increasingly flimsy argument of our corporeal bodies being synonymous with our souls, the way we capitalistic humans use and abuse each other for our own pursuit of more capital, more gains, more everything. It even takes the first steps into these examinations, mentioning these types of ideas semi-regularly, especially in the excerpts of lore, NPC diaries, and straight up excerpts of cyberpunk novels you can find and read throughout Night City. But it can’t commit the time to going any step further than a mention, an obligation, a checking off from the list of cyberpunk tropes. It has too much other stuff to show you, too many nooks and crannies to populate with more cyber-weirdos spouting cuss-filled cyber-slang, too many opportunities for leveling up and sidequests and all the other trappings on their list of open-world video game tropes. I don’t want to happen upon a genuine cyberpunk statement in the middle of the story; I want the story itself to make the genuine cyberpunk statement.

And, well, even when the story tries to make a genuine cyberpunk statement, the shoehorned tropes of open-world games get in the way regardless. The transition from Act 1 into Act 2 is genuinely surprising, engaging, interesting, and feels authentically and originally cyberpunk. Doing my best to avoid spoilers, this moment blasts Reeves into a position as main character about as literally, abrasively, and engagingly as I’ve seen in a modern video game, flinging you into a sequence that plays differently than everything that’s come before. When we come back to our previously set up base reality, with our previously set up main character of V, the explanation for what just happened is appropriately mind-bending, gut-punching, and game-changing. It corrupts the heretofore standard first-person perspective into something more, making a compelling argument about how a cybernetic future can and will confuse our ideas of identity, consciousness, and ownership. It adds a new piece of narrative stakes that shatters the trope-laden ground covered thus far. I could not wait to dive into the story of Act 2 now that these elements were present.

And when I tried to, I was, simply, bombarded. “Don’t forget this is an open world!” the game shrieked at me, blasting me with a wild amount of side job notifications, many of which were for the utterly stakes-deflating task of “buying a new car”, completely ripping me out of the newly found sense of immersion communicated. It’s hard to engage with an excellent storytelling decision, full of intention and muckraking, when the very next moves of the game constantly ask me to disengage, to keep exploring the shallow width instead of diving deeper into any sort of previously stumbled-upon meaning.

In this moment, a moment I’d not experienced in any other open-world game I’ve ever played, I had my “Matrix unplugging moment,” the largest and most painful running into a wall yet. Cyberpunk 2077’s wielding of the open-world genre inadvertently exposed a fundamental limitation: It’s hard to move forward when the genre itself wants you to move sideways. For players who are more interested in milling around, engaging with Night City and its various side jobs, and focusing on “exploring” in sacrifice of every other compelling facet of video game storytelling, this likely won’t be an issue; it will be a feature, not one of Cyberpunk 2077’s many other bugs. But for me, even compared to the game itself crashing in every play session, this is the biggest reason of them all to stop playing.