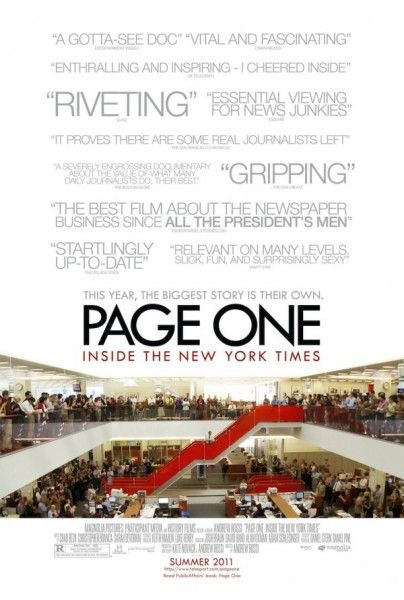

Veteran New York Times writer David Carr is one of the paper’s most colorful and passionate advocates and is at the center of director Andrew Rossi’s compelling new documentary, Page One: Inside The New York Times. The film gives us an up-close look at the vibrant cross-cubicle debates and collaborations, tenacious jockeying for on-the-record quotes, and skillful page-one pitching that produce the daily miracle of a great news organization. What emerges is a nuanced portrait of journalists continuing to produce extraordinary work under increasingly difficult circumstances.

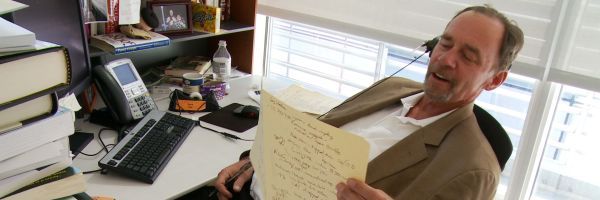

We sat down with Carr at a roundtable interview to discuss his thoughts on the fast-moving future of media and its impact on the fact-based, original reporting that has helped to define our society. He talked to us about print journalism’s metamorphosis even as his own paper struggles to stay vital and solvent and what it was like grappling with existential challenges from players like WikiLeaks and the impact of new platforms ranging from Twitter to iPads. He also shared his views on readers’ expectations that news online should be free.

Q: Did you ever have any qualms about becoming one of the central subjects of this documentary about The New York Times?

DC: Andrew and I met when he made a movie called “A Table in Heaven” that involved Sirio Maccioni and Le Cirque. I was out doing a video piece about him. I don’t know what I did in the movie. I can’t even remember, some hambone, whatever it was, just started talking and then I saw the movie and I thought boy, this movie is really good. He was interviewing me for another documentary he was doing about Web 3.0. I don’t know what it was – and he decided at that point “I’m going to make a movie about the media meltdown and I’m just going to shoot over your shoulder.” And I said, “That’s fine. Why don’t you talk to my bosses about it” thinking they’re going to say “No way!” And they’re like “Fine. Go ahead.” I was so surprised. So then, I had Andrew with me all day, every day for four days. And, after about the fifth source freezed up in front of him because the camera was there, I just turned to him and I said “You might get your movie and I think, by the way, it’s a crappy idea for a movie, but you might get your movie. I’ll never get my story with you here. So I can’t do it. If you would broaden out to some of my other colleagues, I’ll participate, but I can’t have you with me all the time.” It’s personally unpleasant, number one, even if you are like me sort of a little bit of a ham and after a while that wears off and all you see are these big cow eyes just staring at you. All you’re going to do is make a phone call and you feel stupid. I think that turned out to be really important for the movie that there were other characters in it. Now after he made it, then he kind of narrowed back in on me and turned me into this kind of action figure that resembles me a little bit but isn’t really me. I’m not that interesting. My daughter saw the movie and said “Dad, you’re always yelling at people.” And I said, “That’s just the way the movie worked out.” I was not convinced that there was really a film there. Newsrooms are really boring places and they’re full of pasty-faced white people and really long, drawn out discussions and phone calls that don’t work out, and I just thought where is the movie in this. And I didn’t really know until I saw the movie that somewhere in there things had happened and he didn’t just make a good documentary. I think it’s a real movie.

Q: The film presents almost an equivalence between internet-based news media and traditional, mainstream media as represented by The New York Times. But it seems to me a lot of the stuff that’s labeled as news on the internet is unfiltered and has not gone through the editorial process. What is your take on that?

DC: There have been some films about journalism, some of them successful, some of them not. I think one of the really cool things about this movie is that it does a great job of demonstrating the role of editors in the news process in general and their value in the current age. I like to think that I’m a smart person with good instincts, but if everything I thought went flying out onto the web without any kind of intermediation (inner mediation?), you probably wouldn’t think so. You see Bruce (Headlam), my editor, in the film. I mean, stories come along and he’s like [makes sound of pulling trigger of a gun; pretends to be skeet shooting] blowing it out of the air and that’s a necessary act if you ask me. I’m a person with a lot of good ideas. Some of them are good – you know what I mean – and I think that the value added in terms of well I’m going to report two more weeks…now I am blogging and doing my column while that’s going on but I do get the two weeks and I did get to go up to a place I have in upstate New York and write that story for a week. I just did a big heave for Page One for him and right before I walked into the room the edit was there and it’s like “Your top is your bottom, your bottom is your middle, and your ending sucks.” It’s like “Wow, I thought I wrote a really good story.” But experience has shown me he’s probably correct. I give him 1500 words for my column every week. He gives me 1100 back. Now there are other writers like Brian Stelter in the movie. A lot of times he can just go to the web with his first thought and he’s a very clean writer and he’s used to being his own grandpa as it were. That might be fine for him. That’s not me though. And I think, in general, the idea that people are seeing information on the web, putting a little topspin on it and then keeping it rolling and thinking that they’re participating in the news ecosystem is baloney. That’s just putting some sauce on what someone else did. The web, in general, is sort of a self-cleaning oven in that things tend to move from wild rumor to what is known toward an actual narrative that we all hold in common. But what’s doing a lot of this usually, if you look into the links on Twitter, if you look into what people are talking [about] on Facebook, is phone calls that people like you or me make. The idea that we can all crowd source our way to some greater truth is a folly. It isn’t really going to happen. There has to be a model of coming to a newsroom where women and men in a room call people more interesting than they are, that know things that they don’t know, that are then written down and conveyed to the general public in a comprehensive way.

Q: When there were cameras on your colleagues, did you notice the effect of being on film?

DC: One of the things you’ll notice in the film is that it’s mostly men on camera. There were at least two really talented women in the Media Department – Stephanie Clifford and Motoko Rich. Both of them, I can tell you just from a standing start, are probably smarter and better than I am, really well spoken, brilliant journalists. Andrew worked them and worked them and they’re like “No thank you.” So, there’s that effect. Is there a gender difference that men are more than willing to conduct themselves as banty roosters and strut around and self-promote and feel what they do or say is really important? I think so. In terms of are you seeing the real, actual people on camera? Totally. The guy was there 14 months so he starts to become wallpaper. If you spend time in newsrooms, there are some very authentic newsroom moments in there. For instance, Brian Stelter is working away on his WikiLeaks story, typing away really, really fast. Bruce is there and says “Did you send it?” “Yes.” “You sent it?” “Yes, I sent it to you.” Bruce just pivots and looks at the camera and says “He’s lying.” Now that is the fulcrum of what news is about. You’ve got the guy or girl in the corner typing away, trying to make it better. That’s what Brian’s doing. He’s just trying to make it a little bit better. He’s up on deadline, trying to make it better, better, better. The other guy is trying to, number one, get it in the paper, but number two, make sure it gets there in an efficacious way. Both of these are virtuous pursuits. Both of these are appropriate goals. They’re in conflict at that moment. As somebody at the newspaper and very high up was saying, “I don’t like that he’s saying one of our reporters is lying. That’s bad.” And I just said, “This is the crux of what we do. It’s the absolute.” It’s my favorite moment in the film because everybody’s trying real hard to make it good. Right?

Q: If the model of journalism that you talked about could be preserved -- the traditional way of a reporter ferreting out the facts and an editor pressing him to make sure that it’s relevant, understandable, and accurate -- is it so important to preserve the physical newspaper?

DC: One thing I would point out is all those assets arrayed over a very talented group of women and men at The New York Times doesn’t always ensure that things work out. As the film points out, there have been significant breakdowns in our organization. Jason Blair was a good friend of mine. I never knew what he was doing. Judith Miller was a huge asset to the paper until she was not. So, however noble that process is, it’s not foolproof. We’ve learned things. In terms of, is that a necessary correlate to a physical artifact that plops out every day? No. It’s about a brand called The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal or the Los Angeles Times or Slate or whatever. It’s branded information put together by people that you trust such that you believe it when it is said and I don’t think that that’s something that is necessarily a byproduct of the physical production of an artifact that goes plop on your doorstep every single day. But I’m a sucker for the daily paper and not just ours. I get four papers every day at my house. I’m as webbed up…I mean, it’s sort of a trope of filmmaking that I be somewhat of a luddite and a defender of old media in the film. But, in fact, I have 300,000 followers on Twitter. I was one of the first bloggers at The Times. I’m deeply involved in the so-called digital revolution that is underway. Nonetheless, what looks like a silly exercise, that Page One meeting where they’re deciding what are the seven most important stories in the Western Civilization that day, I find extreme value in that. I find [value in] the curation, the ordering, the creation of a hierarchy in which we preserve a certain idea that we all hold in common about what is important now. In fact, we make it up. It’s just a guess. But I find value in it so there’s a discipline that goes with making a physical artifact that is not the same as the web but has a significant value both to me as a consumer and to the broader culture at large.

Q: What’s your opinion of The New York Times using WikiLeaks as a source or a partner? How would you characterize that relationship?

DC: I think we’ve had a very complicated relationship with WikiLeaks. First, they were a subject. What are these crazy guys doing? They aren’t anarchists. What are they up to? And then, WikiLeaks decides it isn’t ubiquity of information that drives the bounce that creates an appetite. It’s scarcity. And so, just plopping it out where you or I or anybody could grab it doesn’t make much of a noise. And then they decide, you know what, we’ll give it to certain media outlets. We’ll partner with The Guardian. We’ll partner with Spiegel. We’ll partner with The New York Times. And not only will we get the advantage of their megaphone, but it’ll engage the competitive instincts of journalism. And the other thing we can do is we can harness their muscles, and so, although we don’t necessarily believe in redaction, we know they will redact and limit the damage of this information coming out so it’s a way for them to create a kind of ad hoc hybrid form of media. And WikiLeaks’ view was they were a co-equal partner in that information. I don’t think that was our organization’s view, and when I say that, I only know what I’ve written or what I’ve reported. It’s not like they consulted me. They usually listen very closely to me and go the other way as fast as they can. So then we’re sort of partnered with them and then we get in a fight with them and they don’t want to partner with us but then some of their partners partner with us. And then, the final pivot is back to subject again when Julian Assange becomes a subject of significance. What’s interesting about the movie is Andrew saw it right away as soon as that WikiLeaks stuff started. We’re all like “What is WikiLeaks…?” and he knew. He knew! And that scene where you see Brian looking at the Apache video, and Stelter knew to his credit, but the rest of us “What is this?” as we’re really trying to come to grips with it. What this is, is a paradigm shift. And when Bruce talks about somebody who wants to take a closed system of information and crack it open, I think it’s a really good example because WikiLeaks … We are not, as a media organization, reflexively against the State. We don’t believe that the State should not exist. I mean, State Capital apparatus, but Mr. Assange believes that all State apparatus are intrinsically corrupt and that they’ve got to throw sand in the gears of what’s going on. So we end up in sort of a weird place where we don’t really have objectives in common but we’re working with the same information.

Q: So many people get their news online or from TV these days. How much longer do you think the print medium will continue and will we still hear the plop of the newspaper on our front steps?

DC: I don’t think it’s that important that there be a physical artifact. I’m of the belief that print product will be a luxury artifact going forward and if you want to signal to people that you’re a person of a certain temperament, you’ll have a very expensive, nice newspaper tucked under your arm when you get on. The iPad will not convey that. It will not. But it’s important that these evolving business models including our metered model begin to point a way forward where the same level of news gathering is supported whether there is the plop of the newspaper. The reason we’re all hooked on that plop sound is that’s how we eat. We put the white paper out so we can get the green paper back. Economics on the web, there’s no equivalence between a digital customer and a print customer and until we create a kind of scarcity in ads. I mean, the problem with the internet is information ads double two times every year and of course spaces are going to go down. So we have to make brands mean something and part of what we do when we erect a wall around our content is we create a new business and say “You know what, these people have opted in, and if you want them, it’s going to cost you a little more money.” So we’re expecting more value for the consumers and from the advertisers as well. I’m a romantic about the plop. I like the plop. But it isn’t really why I go to work every day. If I’m on Page One or if I’m on Most Viewed, they’re both pretty exciting moments for me.

Q: You were among the first bloggers at The Times. What about the relationship between the online version vs. the print version of the material? Does someone check back to compare it with the original source material?

DC: I think the muscles we have in print are on manifest display in digital realms and I think that our second iteration of the web in like 2002 demonstrated that the men and women who make The Times website are in fact Times men and women and that we have 40 million uniques because we happen to be good at the news business no matter what the platform is. That’s my little infomercial but I strongly believe that.

Page One: Inside The New York Times opens in theaters on June 17th.