As the director of some of the best films over the past fifteen years (Fight Club, Zodiac, Seven, The Game, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, The Social Network), David Fincher is considered by many (myself included) to be one of the best directors working in Hollywood. Unfortunately, while he makes some of the best movies, he rarely grants interviews and is reluctant to talk with the press. So when I was offered the chance to sit down with him earlier today to talk about his latest masterpiece, The Social Network, I jumped at the chance.

While the interview was scheduled for thirty minutes, we actually ended up talking for almost fifty! During our lengthy conversation we discussed making The Social Network (which gets released on DVD/Blu-ray January 11th), the way he makes movies, future projects like The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and why he does so many takes. If you're a fan of this brilliant director, hit the jump to either read or listen to what he had to say. I promise, this is one interview you don't want to miss.

If you're a film nerd like me, I'm sure you'd rather listen to what Fincher had to say rather than reading a transcript. So click here for the audio.

However, I know a lot of you might not have the time to read/listen to the entire interview. Here's a few bullet points from our conversation:

- The Game is coming to Blu-ray! Criterion is working on it right now. He's been sent the first 3 reels to watch but hasn't had the time yet to actually watch them. One of the big holdups is because Gramercy was purchased by Universal, Criterion has limited funds to work with. Also, he doesn't like to revisit his movies, which delays the process.

- I asked him if he might ever direct a romantic comedy. He said, "I sort of thought Fight Club was a romantic comedy [laughs] but albeit very homoerotic..."

- During the commentary track for the Blu-ray, he gave out Aaron Sorkin's email address. Sony, of course, beeped it out.

- Many other things were beeped out even though the disc comes with a warning that protects the studio. Fincher was frustrated with the beeps.

- Talks about how he was going to do American Gangster when it was called Superfly. He thought the movie needed a budget close to 100 million dollars. The studio thought it should be 45. That obviously didn't happen.

- Answers why he got a thank you in the credits of Wall-E

- Since he shoots so many takes, on the Blu-ray I learned that they had shot 268 hours of film on The Social Network.

Regarding the way he shoots and the amount of takes:

"I want stuff to play as wide as possible. I want to be able to see… if I could play the whole thing in a master and it could be compelling enough, that’d be great. Then it simplifies my day, it simplifies life for the actors when you could just focus on that. But by the same token I don’t want to be forced into coverage. So I want it to be as good from every angle and I need to get as many of the kind of shadings that I want from every angle. So, 40 takes is… again, there is so much hyperbole when it comes to this and I think we probably average a little over 20, 23, 24 takes, on average, per shot."

Talks about how he'll keep track of the takes on set and they enter it in a system called PIX. What they end up doing is using parts of certain takes to create what you finally see. Explains that he'll use the beginning of take 14, the audio from take 18 and the ending of take 20. He said,

"We have a system called PIX that allows me to not only make circle takes but really, really intricate notes and then I get the dailies. I may not even print the first eight takes. I may not even have it. I may just go, “I just didn’t feel it. It felt mechanical. But take 14, they really snapped in.” So it’s really those six takes, from take 14 to take 20, those are what I want on that side." He goes on to say, "So you might shoot 20 takes and in those 20 takes with two cameras, you might say I love take 14 for most of it, but you’d gotten off on the wrong foot. So take 17 actually has the best sort of beginning, and that’s kind of the skeleton of the thing. I want to build the scene around this so I’ll say that my star take is take 14 for most of it. I love the beginning of take 17. And take 19 and 20, they nailed the ending. We know we’re going to be ending on that. So now, for the most part, the scene is being built around those things and now you’re shooting other pieces that support those takes."

Another thing he talked about was making concessions to put more money into performance. He describes how some directors like to have a Technocrane on set at all times. But a Technocrane is $3,000 a day. Fincher explained:

"Well, $3,000 dollars is a meal penalty. So, if you don’t have that (a Technocrane), you can go another 15 or 20 minutes right before lunch in order to allow for that person to do something better. So I look at it as, I’ll always trade helicopter shots, steadicams, and that stuff in order to have the time to let somebody fail upward."

Talks about that while he wants to be as accurate as possible, you just can't make everything perfect. A great example is when Jesse Eisenberg's crossing the street in Harvard Square in The Social Network. While the movie is supposed to take place in 2003, cars from 2007 and 2009 are driving by.

For fans of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, he says they are also going through the same thing on that film. Meaning you have to make choices on what time frame you're going to work in. He says:

"What year does it take place in? Well the books are delivered in 2004, so he’s probably thinking in terms of 2003, it’s not published until 2005, 2007 is the iPhone, so all those apps that would be available to the iPhone are probably something that Salander would have access to ‘cause she’s a bit of a Mac junkie. So you kind of go, “Well where do we draw the line?” So we just said, look everything has to be pre-iPhone technology, because otherwise they would be sitting there going “Well we just go over here.” They would have a compass; they would be able to tell what the weather was like. So there’s all that stuff, you just have to make a decision [that’s] fairly arbitrary, basically everything in the movie is pre-iPhone."

He went on to say one of the reason he took the job directing Dragon Tattoo was that Sony wants to make a "franchise movie for adults." This was after he got over the fact that he originally thought "you cannot make another serial killer movie…you’ve got to fucking stop this.”

On other future projects, he said that Chef is dead. He calls The Reincarnation of Peter Proud a "great script." Confirms 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea will be in 3D, and he also talked about Rendezvous With Rama - which he hopes to do with Morgan Freeman. Regarding Rendezvous With Rama, he said:

"Rendezvous With Rama is a great story that has an amazing role for Morgan Freeman who is an amazing actor and would be amazing in this thing. The question was can we get a script that’s worthy of Morgan and can we get a script that is worthy of Arthur Clark and can we do all of that in an envelope that will allow the movie to take the kinds of chances that it wants to take. ‘Cuz we want to make a movie where kids go out of the theatre and instead of buying an action figure they buy a telescope. That was the hope. The hope is, let’s get people interested in the fucking movie. So there have been people that have been interested in this idea and we have never been able to get a script."

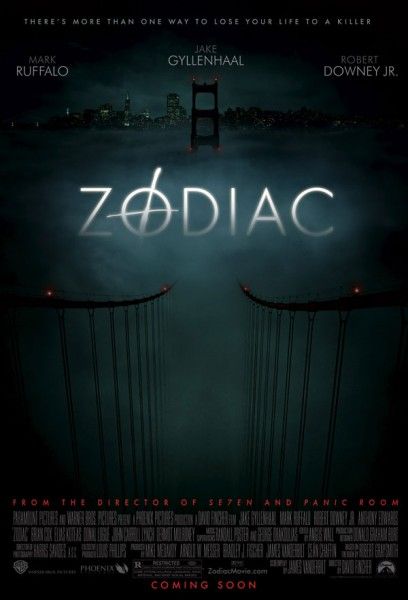

And for fans of Zodiac, he talked about how he had to make certain choices to make that film work. He said:

"So in doing all of the leg work and trying to turn over as many rocks that were, would either kind of tear up the fabric of what Graysmith was the proponent of or support what he was a proponent of. You know, you would get stuff where you just go “We can’t include this. This is a really interesting, dramatic fisher that we’d love to follow, but we don’t have enough data to support it as being part of our narrative.” So even though it was maybe 3 or 4 chapters of Zodiac Unmasked, we couldn’t go there."

Finally, after talking with him, if I were a betting man, I'd say that he's doing 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea as his next movie after he wraps The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. While he didn't exactly say it... just the way he answered my questions made me think that was his next project.

And with that... here's the full interview. Let me know what you think in the comments. Are you a Fincher nerd like me?

One last thing, a HUGE thank you to David Fincher for giving me so much of his time while he's busy on another project and to everyone that made this interview happen... thank you! And if you haven't seen The Social Network, what are you waiting for?

Collider: I usually have fun with my first two questions, and my first one is: so what did you really think of The King’s Speech.

Fincher: You know what, I just recently saw it and I thought it was beautiful.

I agree. A lot of people in town, and I know awards are whatever, but a lot of people in town are saying it’s your film and The King’s Speech, that’s what everyone’s talking about—

Fincher: Black Swan is pretty amazing.

I agree, I think the film’s unbelievable.

Fincher: And I love Winter’s Bone, I thought that was, I thought she was stunning.

There are some amazing films.

Fincher: So, you know I don’t know, I mean more power to everyone. You know, if you’re gonna hold a pageant…

(laughs) Are you sort of surprised though, at the critical acclaim for your film? Because you never really know, I mean it’s such a modern story, and it seems to be universally loved [by] critics, audiences, were you sort of prepared for that?

Fincher: No, you know I wasn’t prepared for it and I actually wasn’t here for it. I mean we finished the movie probably 3, 4 weeks before the New York Film Festival, and I got on a plane and went to Stockholm, and then I got on a plane [and] came back for the opening, and then went to work. So I kind of haven’t really had a chance to assess, cause I’ve really been (laughs) on to other things. So, it’s always nice to be liked.

Jesse Eisenberg has told me that you read a lot of stuff, that you’re aware of things. Is that true or not true? Do you read what people are saying online? Are you an online junkie?

Fincher: No, I mean I think when you’re marketing a movie you have to be—I certainly was aware, when we went to Mark Woolen to do the trailer for The Social Network, we knew that we had a perception issue, if not a problem. People thought we were making The Net or we were making, you know what I mean? That we were making something that was slavishly beholden to technology, and so I said to him, and he’s exactly the right guy to kind of give the most obtuse of brief that you can, cause he’s more than kind of a genius. So I said to him at the time, “I’m not giving you a huge task, you just need to make a trailer that makes sense out of why anybody would make this movie, go do it.” So I was aware at the time that there were people saying, “A movie about Facebook? What the fuck?” I think that they thought that we were making a roller-disco movie or something, that we were kind of fad-hopping or something. And to be honest, when I read the script I didn’t really—I mean my daughter’s on Facebook, so I’d seen it, but I wasn’t versed in what it does or what it could do.

And when I read the script, at the end of it I had even less of an idea about what the technology itself did, as much as I was aware of the acrimony behind the development of it. So I try to be aware of hurdles as it relates to perception, if you’re trying to play in or play against, or what you need to inform the audience of. But once the movie’s done, you’re kind of like, if you read the good reviews you gotta read the bad reviews. I kind of think of it as like being a quarterback: you get way too much blame when it’s bad and way too much credit when it’s good. I kind of try to keep it all in perspective, so I’m not that up on prognostication, and I’m not that up on—I was aware of when you go on press junkets they tend to go, “here are the journalists and here’s what they’ve written” but I haven’t really done too much of that, and I didn’t really have time to do when I was in Paris and when I was in London doing press. I wish I did more, but I don’t.

I understand. How does the final film compare to what you originally envisioned before you started filming?

Fincher: It’s pretty close. You know, always with a movie that’s so specific to a time and place, you know we wanted to capture the feeling of Harvard. We wanted to capture the feeling of what it was like to be a sophomore in the dorms at Harvard, in as much as, we want it to feel like that even though that we weren’t being allowed to shoot there.

If I can interrupt, I wanted to follow up to that. I love your movie Zodiac, and it’s such a stickler for authenticity, and you were not allowed to film at Harvard, and I know that that must have hurt. Was it ever a deal-breaker for you?

Fincher: No, and this goes with part of what I ended up gleaning from the experience [of Zodiac]. You know Zodiac, there was a piece of material that was purchase that for no fault of the author was not embraced by a lot of Zodiacologists. So, you know a lot of people thought that Graysmith’s take was—you know that he was a crackpot or that his view of it they didn’t share, but that’s the movie that we were making. So we did the research from that standpoint, here’s the story that we’re telling, you know here’s the Dave Toschi story, it’s the Robert Graysmith story, it’s the Arthur Leigh Allen story. So in doing all of the leg work and trying to turn over as many rocks that were, would either kind of tear up the fabric of what Graysmith was the proponent of or support what he was a proponent of. You know, you would get stuff where you just go “We can’t include this. This is a really interesting, dramatic fisher that we’d love to follow, but we don’t have enough data to support it as being part of our narrative.” So even though it was maybe 3 or 4 chapters of Zodiac Unmasked, we couldn’t go there. As it related to what Aaron [Sorkin] was doing—I think the thing that was depressing about not getting cooperation from Harvard was, when you really go to Cambridge and you walk around you go, “Oh my God!” you know with a 2000 ASA camera and a very very small crew, if they would give me access to what’s behind the walls here, I could make this movie really really cheaply and efficiently. But then you go, “Alright well we’re not gonna be able to do that, so now colonial architecture that looks like, okay so now we’re in Johns Hopkins, now there’s a unit move and we have to do that stuff there, and then we can’t shoot in any of the dining halls so we have to shoot a dining hall at USC.”

So we end up cobbling stuff together that’s thousands of miles away or that’s near the soundstages [where] we’re gonna shooting. So as much as we would have liked to have had the authenticity of being able to shoot in the Kirkland dormrooms it wasn't in the cards, so you kind of go, “Is it my job to recreate everything down to the n’th detail, or is it my job to tell the story of four or five points of view on the same issues?” So having gone through it on Zodiac, and trying to have been as—and again I had a couple of advantages, one that I grew up in that area and I remember what it felt like to see that Oricon 16mm reversal footage of kids on the bus being driven to school, and being one of the those kids, and remembering what the kitchens were like at my friends’ houses and what the cars were like, and the kind of space you felt like in the Pontiac Vista Cruiser of the day, you have an advantage of knowing—the feeling of this is important, but the actual details of it are not. You know I’ve never been to Harvard, I’ve never been to college, so I don’t know what dorm life is like. I mean I was interested in different kinds of fraternities than a lot of kids my age, because I wanted to be in the movie business. But I comport some of those feelings and that sense of wanting to be allowed into the sandbox, or wanting to have control over one’s vision or dream for what something could be. So I could relate to all those things, although I have no idea what it’s like to write HTML or code anything, you know I don’t do that. So I could look at that stuff and go, “I think this is an important part of the sequence, but I also know that people typing on computers is boring so we need to get through that part of the film as quickly as possible.”

There’s a shot that I love in the film, and I’ve watched on the extras and how you put it together, it’s when Jesse is running through Harvard Square, with a mime with lights in the archway, you have three cameras on the roof across the street. Did you ever think you were gonna get shut down really? Or was it sort of like, “we can pull this off?”

Fincher: No, you would never spend the kind of money that we spent, with the notion that in all probability that they were gonna come and the police would hand you a ticket and ask everyone to leave. That’s probably as close to anything that we did that we need—well no actually we stole a thing at Lowell that we didn’t have permits for. But no, you know it’s all calculated risk. You’re always looking at it going, “Do I really think, in the end, that anybody on the Harvard side of the wall gave a shit that we were on the bank across the street? Probably not.”

Were they watching you across the street? Did they know that you were there?

Fincher: No, no. We had to pull a permit with the city to put a 5k up on a roof that could possibly beam people’s eyes, cause it’s a safety issue. So in-between takes, when Jesse’s going back to one, we had to flag that light or turn it off. And you know there’s just certain things we have to do, because we’re in the flow of traffic, we don’t own all those vehicles, they’re not all ours. But the question—you know it’s supposed to be 2003, there’s cars from 2007 and 2009 in that shot, and it’s not like we said “Okay stop, sort through, I don’t want anything past 2003 on the street!”

(laughs) I didn’t even think about that.

Fincher: Well you get asked these questions, you know we’re going through this with Dragon Tattoo now, what year does it take place in? Well the books are delivered in 2004, so he’s probably thinking in terms of 2003, it’s not published until 2005, 2007 is the iPhone, so all those apps that would be available to the iPhone are probably something that Salander would have access to ‘cause she’s a bit of a Mac junkie. So you kind of go, “Well where do we draw the line?” So we just said, look everything has to be pre-iPhone technology, because otherwise they would be sitting there going “Well we just go over here.” They would have a compass; they would be able to tell what the weather was like. So there’s all that stuff, you just have to make a decision [that’s] fairly arbitrary, basically everything in the movie is pre-iPhone.

On the extras, I learned that you guys shot 268 hours of material on your film. Obviously, you’re not going to sit there for 268 hours and rewatch everything. I’m curious, you’re known as a filmmaker that does a lot of takes. When you’re on set, say you do 40 takes or something, do you know on set that take 38 and 39 are the ones I really care about or are you giving all those takes to somebody—you’re editing team—and saying watch them all, what do you think?

Fincher: No. It’s like you’re building a creature from the marrow, out. You are starting at the center of each limb. So you’re deciding, “OK, well, this scene, the important part is the intent.” The marrow is sort of the intent of the thing. It’s supposed to do this. But then, look, it needs to really have powerful legs so we need bigger bones back here. And now we’re going to need a lot more muscle on this part. So you’re building what each scene has to do based on… in a rehearsal you’re going, “Well, what’s being done in terms of the psychology of where people are sitting and how they should be presented.” Whether they’re in the eye-line or outside the eye-line and so you rehearse based on that and then you decide on the coverage. Based on the coverage—and I have a couple of rules of thumb—I want stuff to play as wide as possible. I want to be able to see… if I could play the whole thing in a master and it could be compelling enough, that’d be great. Then it simplifies my day, it simplifies life for the actors when you could just focus on that. But by the same token I don’t want to be forced into coverage. So I want it to be as good from every angle and I need to get as many of the kind of shadings that I want from every angle. So, 40 takes is… again, there is so much hyperbole when it comes to this and I think we probably average a little over 20, 23, 24 takes, on average, per shot. Maybe even in some cases a little bit less. If you’re talking about somebody running from right to left, you’re talking about in the teens.

When it gets into the performance stuff, we may have six people at a table so you have master, 3/4s from this side, which is over one guy’s shoulder seeing the other three people on the other side of the table. We may do a complimentary of the same thing on the other side. But then you go, “OK, most of the lines are being delivered by him.” So Zuckerberg’s lawyer is talking for the most part, and Zuckerberg is being less than interested. So we know that that coverage is going to pivot mostly off of that guy, but we want to be able to see an over-the-shoulder from here and an over-the-shoulder from here, to tie him into these people. So, we’re going to do those. And now we’ve got to do a special just on Zuckerberg and the foreground in focus and his attorney out of focus. What you find as you’re shooting is, “That’s a really interesting thing that you’re doing there. I think you should do one that matches the master but also do one where you go ahead and steal the tension by looking at your notepad or writing something and sliding it over to somebody else.” That’s a nice idea. So, each bit becomes a further exploration of the scene. So you’re starting wide and you’re moving in and so I may have six setups for something that’s a page, page and a half, which is short for an Aaron Sorkin scene. A lot of the scenes are six or seven pages. So you would go in and you kind of explore; it’s vivisection. You want to stay alive but you also want to see how all the parts work. I will go through and probably the first four takes I’m not giving much direction. We’ve done a rehearsal and we’ve talked openly amongst everybody about what the intention is, so they’re doing their thing. And then by take four or five, I’m going, “OK, I feel like the guy who’s leading the whole thing seems like he’s behind the eight ball, so I need to concentrate on getting him to move–everything’s pivoting on him—so I need to refine him.” And then as I’m refining him, I’m seeing what these guys are doing over here and I’m going, “OK, when I get into coverage, I need to make sure that I’ve got stuff where they’re not interested and stuff where they’re pretending to not be interested and stuff where they’re really interested in what’s going on.” So I know that I need those three options when I get onto this side.

So it becomes kind of fractal. You’re kind of discovering the space between moments where you go, “Oh, it’s actually really interesting to watch the other attorney and how the attorney doesn’t seem to be at all afraid of what Zuckerberg’s attorney is saying.” He’s just waiting to talk. He’s not even listening. He’s just waiting for the guy to get done. And the Winklevosses are over here going (thud), “I just want to scream. Can you believe what this guy is saying?” and their attorney is going, “Guys, this is what depositions are about. They’re going to try and show you what they have and decide whether or not you want to continue with this process.” So, all of those things are what you’re juggling. To answer your specific question, you might get four or five takes where you’re letting… Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom. You’re just letting the actors go. And then you start to refine. In the process of refining you find other things that are interesting; “that’s good. Play that. I need you to go back to that thing that you were doing at the beginning where you were sort of rushing through this. That one thing that he says, I want you to snap to that and be interested in it.” So that informs that and then you build toward this coverage and then you turn around. So you might shoot 20 takes and in those 20 takes with two cameras, you might say I love take 14 for most of it, but you’d gotten off on the wrong foot. So take 17 actually has the best sort of beginning, and that’s kind of the skeleton of the thing. I want to build the scene around this so I’ll say that my star take is take 14 for most of it. I love the beginning of take 17. And take 19 and 20, they nailed the ending. We know we’re going to be ending on that. So now, for the most part, the scene is being built around those things and now you’re shooting other pieces that support those takes.

Are you noticing on set that take 14, 17, 19 and 20; “those are my takes.”

Fincher: I’m building this entire scene around that.

So it’s on set that you’re figuring out what takes you’re very happy with?

Fincher: On set I’m going, “We hit a groove at about take 14.” The majority of the coverage is going to be this idea. And we’re going to do everything now to support takes 14 through 20 with take 17 really being the beginning of what I like. And takes 19 and 20 are where they really nailed the ending. So now we’re doing that. Now I’m adjusting what everybody’s doing to support that idea. So now we’re going into coverage on these guys and we’ll shoot four or five takes where they get to do whatever they want and then take six through ten, we’re refining what his attorney is and then we’re going, “OK, now we’re in our groove on this side, let’s do you. I need to get this from you.” I’ll sit there all day to get that little moment where I go, (snaps), “That’s the response I wanted from take 14 on the other side.” Those notes go… we have a system called PIX that allows me to not only make circle takes but really, really intricate notes and then I get the dailies. I may not even print the first eight takes. I may not even have it. I may just go, “I just didn’t feel it. It felt mechanical. But take 14, they really snapped in.” So it’s really those six takes, from take 14 to take 20, those are what I want on that side. Then we go into the close-ups, and there’s a great little moment on take two where he does this little thing, so I’ll keep the whole take but it’s really for that moment. You go through and you sort of make this potpourri. Then that gets shipped off and then Angus [Wall] and Kirk [Baxter] will go through and off those takes they’ll go, “It’s interesting what you’re talking about in take 14 but there’s also this thing happening in 12.” They send it to me and I go, “Oh, that’s true. That is an interesting exchange and I like how the head turn worked on that, so that’s an option.” Then we build a version of the scene from every single angle where it’s just the selects; the best line. And it can often times be just for the audio. “I love the way his voice sounds when he says this. Can it work with one of the takes we end up using?”

I was watching on the extras the way you guys sort of Band-Aid take 14 and take 17, with the visual of 19… How often does that happen in your films? Is it a few times in the movie or is it quite often where you’re doing what you’re talking about?

Fincher: It’s the entire movie.

So it’s quite often?

Fincher: I think Fight Club is a pretty good example. I mean, we have… because there’s so much voice over, and the voice over was recorded two or three times, you may like a read from the February recording voice over for this one line and you may go back to that. So there’s probably, for Edward [Norton], there’s probably 1,300 shots in the movie, and there’s probably 1,800 different pieces to make up those shots.

I’m just thinking about all of that.

Fincher: Yea. But it sounds like three-dimensional chess, but it’s not as elaborate as that when the pipeline is setup to do it this way. You cast a wide net over the whole thing and then you start sifting. It happens rarely, but there are times when we get down to the final cut of something and we go, “We’re going to have to jettison this back half of the scene, as much as we like it, because we can’t get into it; we just can’t make this shift.” You sacrifice a gem for the whole. This isn’t to say that the performance is constructed, but performances are enabled. If I’m going to make people do it that many times, they got to know that if they give me something great, it’s going to be there. To me, the idea is to free people up. I want the mistakes. I want the thing that they do when they are caught not thinking about what they’re supposed to be doing.

I have to be honest with you. A while ago when I heard about your way of doing business, for filmmaking and doing so many takes, I sort of questioned it. But the more I’ve learned about the art of the industry, you have a very rare luxury of having the time to do this many takes and the way you describe your editing process, I don’t think you could do it with only four takes.

Fincher: Well, I’ll go you one further which is… “What the fuck are you doing?” If you’re flying out actors from all over the fucking place, because they’re the right person to read that text, and you’re spending weeks with them in rehearsal, and then you get there and you’re going, “OK, trained monkey, do that thing.” How unbelievably disrespectful is it to everybody’s time? I look at it this way. There are a lot of directors who like having a Technocrane on the truck. So if they decide they want to do a crane shot, Technocrane’s there. OK, well, Technocrane’s fucking $3,000 a day. Well, $3,000 dollars is a meal penalty. So, if you don’t have that, you can go another 15 or 20 minutes right before lunch in order to allow for that person to do something better. So I look at it as, I’ll always trade helicopter shots, steadicams, and that stuff in order to have the time to let somebody fail upward. To let somebody… they know what they’re doing, they’ve figured out who their character is. They’re coming from a solid place of contributing, and now you want to get them to a point where they are no longer thinking about, “Which hand is it? I didn’t pick up the thing…” It’s like, you do something 16 times, you can do it in your fucking sleep. Now, once you can do it in your sleep, now let’s get the words to come out of your mouth like it’s the first time you said it and you always talk like this. That’s what we were doing. So you sit there and you go, “Couldn’t the Winklevosses’ attorneys’ conference room be more marble, more carved wood?” Yea, it can be a much more elaborate thing. Does it need to be? No. Would I rather have eight days in there to shoot that stuff than six days? So if I take some of the elaborateness out and I don’t relight as much, and if I take some of the green screen stuff that I wanted to see out the windows of San Francisco and I take that out of my budget. I go, “OK, the windows can be blown out and just be a glow outside because that’s often what it looks like when you try to balance exposure for the real world to the real outside world.” Am I OK with that? Does it get me two more days with Andrew Garfield? Yea. OK, well, I’d rather have two more days with Andrew Garfield. I’d rather give him nine more bites at the apple on every setup.

It actually makes a lot of sense to me. I know I’m running out of time. The commentary track on your Blu-ray has a lot of bleeped out moments. Are you aware they were bleeped out?

Fincher: Yeah – well they were going to remove some of the stuff that I was saying. Look, you know, I don’t swear that much but over a course of four or five hour commentary that gets edited down to two – I guess the most interesting stuff I say usually has fuck somewhere in it.

I wanted to get a little more specific and say did you really give out Aaron Sorkin’s email address while recording the commentary.

Fincher: (Laughter) I did. Yeah… yeah… but again why do company’s put these things that say the views expressed are not necessarily [of the studio] and then ask you ‘why are you saying that? You don’t need to say that’. It’s like – but I did say it so fuck you and you already said when I put the disc in I can’t even fast forward past the fact that Interpol is going to punish me and that the people who are speaking are not speaking on behalf of Sony Pictures. We got into something about it’s a PG-13 movie and you can’t talk like that and I was like fuck that. That’s the way I talk and if you want to use my commentary, you’ll just have to bleep it.

I completely agree. What are your thoughts on test screenings and what has changed in your films from friends and families screenings?

Fincher: (Pause) Two kinda separate things…

Do you do test screenings on any of your movies?

Fincher: Yeah – I have. I didn’t on this movie because of websites.

I don’t know what you’re talking about.

Fincher: Here’s the thing – there’s no doubt that the blogosphere is an important part of becoming part of a conversation. It’s a place where it’s very democratic and everybody gets their chance to leave their message and chime in. The thing that it has done is reduced the notion of honing. Filmmaking is a…it’s… you gotta have a fucking preseason; you gotta have out of town previews. It’s a communal enjoyment hopefully and so you’re going to have to show the thing to a group of people and it’s become such an incredible clusterfuck as to who sees what first and who’s the first to offer an opinion. It’s a very dangerous, very slippery slope. I know of situations where message-boards are bombarded by publicists that work for movie studios only to be able to bring you a hard copy of see this. This is not just us.

But, I’m just curious, in my opinion you’ve reached a level with your filmmaking and your art that it would seem like you would have a little bit more ability to say no to certain studio people and say we’re doing it this way.

Fincher: But it’s not even about that. It has to do with no one lives in a vacuum. It would be great, if you could, but you can’t. The fact of the matter is somebody, I don’t know who I was thinking of – maybe Martin Scorsese – was saying ‘It’s not about having final cut because that just means that the studio executive can’t talk to you but they can always talk to your wife.’ You know what I mean? And I’ve watched this happen – when somebody asks you the same question thirteen times it’s really hard to stay true because you can answer it ten times but then you’re in the thick of something. Producers, production managers do this all the time - ‘Do you really got to do that? How many extras do we need for that scene?’ and they keep asking you and the more times you get asked you go ‘Fuck, I don’t need twenty five. I can do it with eighteen.’ And before long – ‘Alright, sixteen’. And you start whittling this thing down and in a lot of cases that can be a positive part of keeping the blade sharp. You can’t stay sharp without friction. You got to have it.

But it’s a tricky thing to manage because the people who are paying for the thing that you’re supposed to be qualified to judge and be the final arbiter of have no problem when you say ‘mehhh let me think about it’. They have no problem with that. The second you say ‘you know what, I’m going to go my way’ – that’s what they remember. They always remember that as this ingratitude. It’s like wait a minute this was a discussion – the second it’s no longer a discussion it becomes an issue. So it’s a very difficult thing and I try desperately to make sure that – and this is probably why I’ve walked away from as many movies as I have and why I have movies that I was unable to get started – because I don’t believe in getting people pregnant and sorting it out later. I don’t feel like being held responsible for something and this happens on every movie – I’ve never had it not happen, where they say ‘Why does it cost so much?’ and you say ‘Because of this, this and this.’ And they say ‘Why can’t you do it for seven million dollars less’. Invariably what the question is: ‘why can’t you pretend to do it for seven million dollars less’ – because when you sit down and actually go through, the guys who are the pit-bull and the heads of production at movie studios they’ve done this, they’ve seen movies go over budget, they understand what it is to throw good money after bad, they know what that looks like, they’ve seen that erosive nature of something that trips and stumbles. You trip up and stumble with ninety people, the ripple effect of that is a big deal.

So I always go into the stuff going ‘Let’s decide the envelope and within the envelope, I’ll round from peter to paid paul [the amount] that I can be responsible within. But I can’t lie to you and tell you that I can do this for seventy million dollars when it’s really going to cost seventy-six and turn the balance of power over to you on a daily basis when I say can I have some more period cars, can I have a rain tower, can I bring in a rare projector?’ Because on an hour-by-hour basis, if you’re calling the studio to ask that, then they’re going ‘Fuck. That’s why I’m paying you to make these decisions. I’m paying you to manage the money. I don’t want to manage the money for you via remote.’ And yet they invariably get into the situation where their bosses are saying we’ve made an arbitrary decision in our head that this is worth X to us. I had read Steve Zaillian’s American Gangster – it was called Superfly at the time and I had wanted to do it. I had a phone conversation with the studio head and she said to me ‘how much do you think this movie’s going to cost?’ I said ‘I think it’s probably close to one hundred million bucks. I think it’s probably about ninety million dollars.’ And she said ‘Well, we think it should cost forty-five’ and I’m sitting there going I’ve done Zodiac and you’ve got Harlem, period, Vietnam War – I don’t know how you get there.

You know when you start laying it out, this is what I think it’s gonna be and you start to…invariably if you’re that far off, you know, the discussion never goes further. But if I had been at – if it had been at 90 and 80 – there would have been a lot of pressure from both sides; from my production side and their production side to go “let’s find a midway point.” And that last five million dollars between the 85 if we could have agreed or 80 or the last 10 million dollars…is really…you’re no longer talking about trucks, you’re no longer talking about lights, you’re no longer talking about manpower. You’re talkin’ about the last 10 percent, the finesse, the thing that- those moments...the ability to have the time to get those moments. And I look at the time that the actors are in front of the camera – that’s what we’re all there for…that’s where it has to happen…you know a lot of people look at film production and they go “let’s see…crane’s here, okay. Bathrooms are here, okay. Production trailers are over there, okay. Stars got their trailers okay, makeup’s got power, they got their hairdryers that’s all working, okay. Our job’s done.” It’s like…no…that’s where it begins. When everything arrives is when it begins not when it ends and a lot of people look at production as, as long as everything is there, it’s done…Now it’s his problem you know what I mean. So I protect for a different thing than a producer protects for. A producer protects for, does he have everything that he needs? Okay, well then now it’s on me…

I know I'm running out of time so I want to ask some fun questions…

Fincher: Fun!

Yeah. You get a special thanks in the credits of Wall-E. Why?

Fincher: (long pause) Well I don’t know.

I think I stumped you.

Fincher: Jim Morris brought some people down to the set of Zodiac. I think they wanted to meet Harris and I think that they were trying to kind of figure out how to paint with light in the way…they wanted to be able to think about things in terms of how do you accomplish it in live action as opposed to…and he was very generous with his time and sat down with him, and I may have been collateral thank you on that because…did they thank Harris on that?

I don’t know, I was looking at your IMDB credits today…

Fincher: Yeah I don’t know…

Well next thing. I as a fan want The Game on Blu-ray. There’s rumors that it’s coming to Criterion. Is it true?

Fincher: Uh yes.

Do you know when?

Fincher: I don’t, because I haven’t had time to look at it. Here's what I know...I’ve seen two reels of it or the first three reels and it looked good but I think it’s a question of – because Gramercy was purchased by Universal, I think it’s gone under the Universal home video banner and that they have released very limited funds to finish. And I think that Criterion is having to cobble together…and they’re lovely people and they do amazing work. So I think they’re having to pull every favor that they can in order to be able to make the number work so, I don’t know when that is and I should.

So it’s in the future though…it is coming?

Fincher: I thought it was first quarter of next year, but I’m sure that it won’t happen if I don’t look at the stuff…

I would say that you’re probably involved in it in some way…

Fincher: No, I saw some stuff that looked…you know, again I don’t like revisiting stuff. That’s why I like to put as much effort into finishing it the right way the first time so that you don’t have to go back ‘cuz when you go back it’s like oh my God.

I think the movie stands up though, but again I’m running out of time. Do you ever think – this is really off the wall – you’ve made a number of specific films. Do you ever see yourself making a romantic comedy?

Fincher: Ummm…I sort of thought Fight Club was a romantic comedy [laughs] but albeit very homoerotic and about narcissistic…Yeah you know look I don’t…Dragon Tattoo came along and I was like “Awww fuck man you cannot make another serial killer movie…you’ve got to fucking stop this.” And it wasn’t really even…it was Michael Lynton and Amy Pascal and Scott Rudin to an extent but mostly from the studio side that they were committed to this idea that there could be…that there was a hope that you could do a franchise movie for adults. And I thought “fuck man, I’ve been working my ass off for twenty years, hoping that somebody would say something like this.” And I just thought, you get an opportunity to hopefully pave the way for something like that to happen…you know, that would be a great thing.

Well okay, and I have to say again, huge fan of yours, and as you can see I’m running out of time. I speak for all fans when I ask you about this…you’re listed to a number of projects that are like, for example, Heavy Metal, 20,000 Leagues, The Killer, Chef…

Fincher: Chef movie is dead.

Oh there we go. I was curious also, The Reincarnation of Peter Proud.

Fincher: I’d love to make that movie. It’s fucking great. Great script.

And my question is, do you see any of these projects, like a lot of people get linked to…Guillermo is linked to like 8 different things but he’s clearly making At the Mountains of Madness.

Fincher: Yeah.

So my question to you is, are these projects that are currently being rewritten for you?

Fincher: Yeah.

And it’s just a question of…will one of these pop?

Fincher: It’s a question of things lining up, I mean, you know Rendezvous With Rama is a great story that has an amazing role for Morgan Freeman who is an amazing actor and would be amazing in this thing. The question was can we get a script that’s worthy of Morgan and can we get a script that is worthy of Arthur Clark and can we do all of that in an envelope that will allow the movie to take the kinds of chances that it wants to take. ‘Cuz we want to make a movie where kids go out of the theatre and instead of buying an action figure they buy a telescope. That was the hope. The hope is, let’s get people interested in the fucking movie, you know…ether. So there have been people that have been interested in this idea and we have never been able to get a script. So the answer is, you know, is the story good enough, is the script the best telling of the story, is there an undeniable person to hang it on, is it technologically feasible. All those things come into play.

I’m curious your thoughts on this thing called 3D.

Fincher: I think it’s cool…when it’s done right.

Exactly. Do you envision yourself, in any of your future projects right now, doing 3D?

Fincher: Yeah. 20,000 Leagues will be 3D.

This goes back to what I was saying a second ago. Basically this is what I wanted to ask you. Sony obviously envisions what you’re working on right now as a big franchise. Probably wants to make two or three movies. The question is, would you be able to, after you finish this first one, do something else?

Fincher: I believe that there’s a script that has to be written for the second movie. We have to have an audience that wants to see a second movie. We have to make room for another Bond movie. So there’s a lot of elements that come into play.

So I guess my final question is do you think 20,000 Leagues could be your next film?

Fincher: I think that there’s a lot of movies that could be my next film.

[Laughs] You could be a politician with that answer.

Fincher: Well I mean, it’s the reality of it.

Again, thank you to David Fincher for giving me so much of his time. Finally, I got an early copy of The Social Network Blu-ray to help prep for this interview. It's truly a gem of a home video release and I learned a ton about the film and how Fincher makes movies by watching all the supplements. I'd give the Blu-ray an A. Definitely worth owning. Look for a full review soon.