The Big Picture

- Zodiac breaks from the conventions of crime thrillers, offering a non-traditional narrative structure and subverting common expectations.

- The lack of resolution in Zodiac sets it apart from standard crime thrillers, reflecting the complexities and uncertainties of real-life investigations.

- Zodiac reminds viewers not to trivialize and minimize the horror and pain of true crime, highlighting the negative repercussions of violence and the importance of acknowledging the flaws and imperfections of the world we live in.

Right now, you’re probably thinking: “Oh boy, some online film nerd is doing a David Fincher think piece? How groundbreaking! That’s certainly not a director who’s been covered by every living film student, critic, and video essayist in existence.” Yes, it’s true, Fincher, along with Quentin Tarantino and Christopher Nolan, are perhaps the most over-discussed directors in modern film discourse, and so I apologize for only aiding and abetting such a phenomenon. As someone who creates analytical film content for the internet, I was required to swear a blood oath to the ancient gods of chaos that I would cover Fincher sooner or later, and so, today I pay that debt. However, I hope to offer you something different than your normal Fincher analysis with this article, just as one of Fincher’s films did for his filmography. Because, when it comes to Fincher’s film Zodiac, I think you’ll find that its construction and themes, as well as Fincher’s filmmaking decisions, offer not only an antithesis to the crime thriller genre, including previous Fincher films like Seven, but a critique of modern “true crime” culture as well.

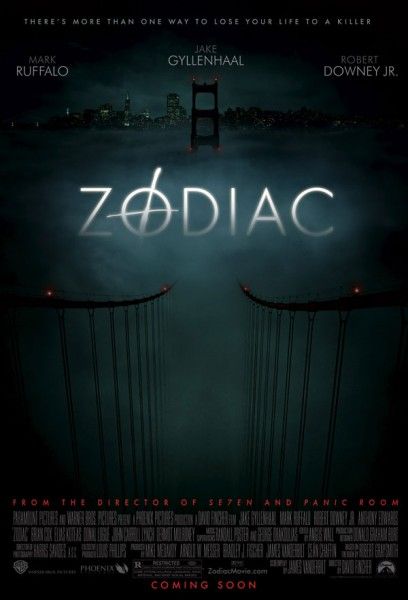

Zodiac

Between 1968 and 1983, a San Francisco cartoonist becomes an amateur detective obsessed with tracking down the Zodiac Killer, an unidentified individual who terrorizes Northern California with a killing spree.

- Release Date

- March 2, 2007

- Director

- David Fincher

- Cast

- Jake Gyllenhaal , Mark Ruffalo , Anthony Edwards , Robert Downey Jr. , Brian Cox , John Carroll Lynch

- Runtime

- 157 minutes

'Zodiac' Breaks From the Conventions We Expect From Crime Thrillers

Let’s start with the conventional crime thriller. Born out of classic detective fiction, like Sherlock Holmes, noir films from the post-World War II period, and TV crime procedurals like Dragnet, the modern crime thriller, as with its predecessors - and most of western storytelling - follows a traditional, Campbellian narrative structure. A traditional crime film, while peppering in red herrings and misdirects for the sake of tension and character development, focuses on the main clues which lead to the discovery of who committed a crime, some form of resolution for those involved, and a lead character who experiences growth or change through their involvement with the mystery. Even the films that flip the perspective to that of the criminal avoiding capture use the same standard structure of set-ups and pay-offs, offering satisfying conclusions and narrative cohesion.

While a movie like Fincher’s Seven bends the crime thriller mold, offering a tragic, more pessimistic payoff and conclusion, it still fits into a satisfying narrative format. The leads and clues Morgan Freeman’s Detective Somerset and Brad Pitt’s Detective Mills discover are productive and useful to the case, leading them straight to the killer’s lair. The place where Fincher exercises subversion is in that Det. Mills does not find positive resolution from his final investigative discoveries, but tragedy - a motif Fincher would expound upon in Zodiac. Though Seven presents this subversion, and a twist in the killer turning himself in due to ulterior motives, the plot still provides the audience with a pay-off to the investigation - revealing the killer, providing resolution to why he killed, and producing a dynamic ending that brings the two main characters' arcs to an end.

'Zodiac's Lack of a Resolution Makes It Different From Standard Crime Thrillers

However, Zodiac isn’t a fictional, plotted crime-thriller - it’s an adaptation of real events, real murders, and a real investigation. Fincher could have chosen to make a film about any number of real serial killer cases, like Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer, or Richard Ramirez, that would have fit into a narrative with a definitive end. Instead, for his first film to be based on true events, Fincher chooses perhaps the case most famous for being unsolved (at least until this very month, although nothing has been proven conclusively). This is a deliberate choice which shows the true aim of Zodiac: to display how, in reality, horrific murders and the subsequent investigations of them are not always direct paths leading to conclusion and a killer caught, but convoluted labyrinths of dead ends, lost accountability, obsession, an ineffective system of justice, and real-world pain.

For those who have somehow remained unaware of the culture-shifting case, the Zodiac was the self-given moniker of an unidentified serial killer active in the greater San Francisco area in the late 1960s. With five confirmed victims and more alleged/suspected, the Zodiac gained notoriety for the taunting, anonymous letters of admission he would send to local newspapers, which were often encrypted via cyphers or cryptograms, as well as for the fact that, to this day, the case remains officially unsolved. With the film, Fincher takes the viewer into the Zodiac Killer case through the lens of San Francisco Chronicle cartoonist Robert Graysmith, who, after being privy to the ongoing investigation at the Chronicle, took interest in the case himself. Taking heavy influence from Graysmith’s 1986 book of the same name, Zodiac follows the case from the Zodiac Killer’s second murder on July 4th of 1969, through the ensuing years of on and off fear and chaos that gripped the Bay Area, all the way into the 1980s when the case had gone completely cold and unsolved. Fincher himself had a connection with the case, having been a child in the Bay Area during the killings, calling the killer “the ultimate boogeyman.”

Part of what makes the Zodiac case, and by extension the film, so antithetical to the standard crime film is its lack of resolution. On the subject, Fincher explained that he was drawn to the initial draft of the screenplay, based on Graysmith’s book, saying: “I liked the idea that there was not a neat ending, But I also find the ending satisfying, because it’s real, it feels true. Some things just don’t get wrapped up neatly.” Zodiac follows the twists and turns of the investigation, from copycat letters and phone calls, to conflicting physical evidence, all seeming to lead to dead ends. Part of what aids the convoluted, unsolved nature of the case was cross-department bureaucracy and stubbornness, as rival police departments for different jurisdictions refused to share evidence and information with one another. Even the music reflects the theme lacking of conclusion, as composer David Shire points out, “The first chord you hear is an unresolved note.” Though Graysmith’s book, and the film, provide a reasonable theory, one favored by many involved with the investigation, to the identity of the killer, Arthur Lee Allen (a theory that has since been contested), Fincher leaves the end of the film ambiguous, drawn from his own doubt, claiming “with someone like Zodiac, even [Graysmith] couldn’t provide an answer.” Fincher made a movie in which there are no solutions, based off a case in which there are no conclusive answers, in an attempt to reflect reality.

With the violence in Zodiac, reality is again enforced. While Fincher opens with a murder that is in slow-motion and traditionally cinematic, the violence in other parts of the movie, like the harrowing lakeside murder, is blunt, realistic, and lacking any sort of flash. It’s almost as if Fincher teases the traditionally cinematic with the opening, only to pull the rug out from under the audiences. Writing for Film School Rejects, Aurora Amidon describes this tease of style saying “Maybe, like Graysmith, you’ll think you’ve got a shot at catching [the Zodiac]. But you won’t think that for long.”

The Zodiac Case Makes Everyone's Life Worse

Compounding on the tragic, complex character arcs Fincher established throughout his career, Zodiac furthers this theme, as all the people the film follows have their lives made worse by the Zodiac case. The Chronicle’s star reporter and a mentor to Graysmith, Paul Avery, played by Robert Downey Jr, is threatened by the Zodiac personally, leading to him giving up the case and becoming a washed up drunk. The detective assigned to the case, Dave Toschi, played by Mark Ruffalo, is able to solve nothing conclusively, eventually being accused (though later acquitted) of forging a Zodiac letter, leading to his removal from the case and the homicide department. Finally, Graysmith, played by Jake Gyllenhaal, is shown to become obsessed with the case, consuming his personal life. In his research, he interviewed hundreds of involved parties, and at one time even going through an entire phone book in search of a single matching number. While he gained success and praise for his book, he seemingly lost two marriages as a result of his all-encompassing fixation on the case. Of the characters and Fincher’s attraction to them, Ruffalo said, “Everyone involved in this spent years working it. They became obsessed with it. Then they became haunted by it. [Fincher’s] interest is the toll it took on people.” There is no open and shut investigation, there is no conclusive suspect. The audience is left with a pile of loose ends, and all those involved in the case, from the victims themselves, to those trying to solve it, had their lives categorically impacted for the negative because of the Zodiac’s terrible acts of violence.

In its antithetical rejection of neat conclusion and satisfying structure that forms the common diegesis of the stories we consume, Zodiac reminds the viewer of one thing - in reality, serial killers are not entertainment, they’re violent people commiting violent acts that have widespread negative repercussions - and I believe such a theme is incredibly important to remember right now. True crime media, and fiction taking inspiration from true crime, is at an all-time high. The current top earner on the crowd-funding platform Patreon is a podcast called True Crime Obsessed, in which two hosts open episodes screaming like peppy, camp counselors, cracking cringeworthy sitcom-esque banter on how excited they are to talk about horrific crimes and people murdered. My apologies to the hosts for being harsh on them, but they conduct themselves with a gauche and morbidly detached positive energy for such serious topics, about real victims and violence, that it feels equivalent to if there was a drag-show on the war crimes of the twentieth century.

With murder-centric cultural phenomena like True Crime Obssessed and the glut of Netflix true crime docuseries, I think a film like Zodiac is important because it reminds us not to trivialize and minimize the horror and pain left in the wake of real world killing. True crime is not fun fiction without consequences; it’s a genre built upon the suffering and death of innocent people. While it’s completely fine to indulge in an interest in true crime or a love of crime thrillers, we should not become pacified and tranquilized by media to be so ignorant we forget the problems and suffering of the real world, letting ourselves be callous and crass to the morbid subject matter it entails. Zodiac was a special movie for Fincher because it was him rejecting the fictional, the pretend - if only for a moment - and acknowledging the flaws, frustrations, violence, suffering, and imperfections of the world we live in. We should all try to keep such a perspective in mind.

Zodiac is now available to stream on Fubo in the U.S.