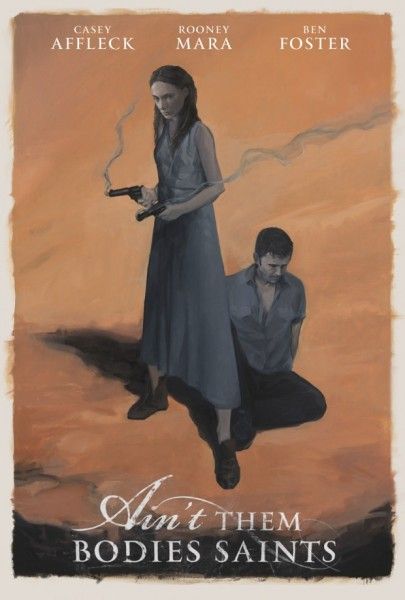

Opening this weekend in limited release is writer-director David Lowery’s Ain’t Them Bodies Saints. The film centers on a young outlaw couple played by Rooney Mara and Casey Affleck who are apprehended by the law and must deal with the consequences of their actions. Affleck’s character escapes prison years later and sets out to find his lover and daughter in 1970s Texas Hill Country. Loaded with amazing visuals and great performances, Ain't Them Bodies Saints is the type of movie that you should definitely see on the big screen in a movie theater. If it's playing in your area, I definitely recommend checking it out. For more on the film, watch the trailer, or here's all our previous coverage.

At the recent Los Angeles press day, I landed an exclusive interview with Lowery. We talked about how the project came together, moving from being an editor to director, if he made any changes since premiering the film at Sundance, the casting process, deleted scenes, film versus digital, future projects, and more. Hit the jump for what he had to say.

Collider: How are you doing today?

DAVID LOWERY: I’m good, I’m good.

What the hell has this process been like for you? You’ve been working for a while, but this is the first big ticket item that you’ve put out there, if you will.

LOWERY: Yeah, absolutely.

What’s it been like for you, this entire process?

LOWERY: There’s been an intense learning curve, but my entire career has been a learning curve of trying to figure things out and learn new things and get better at what it is that I want to do. I’ve also always been hoping that the movies I make get out to wider audiences, and one of the ways to do that to make a “bigger” film. This has been sort of like a culmination of what I’ve always wanted to do with my filmmaking, and also just the next step in the process. As crazy as it is, it also feels very natural because it’s what I’ve been pushing towards. I’m sure there’s more craziness around the bend that I have no idea what will happen. You just very quickly assess the lay of the land for each film, and with this one in particular, you have certain considerations like the scale of it and the budget of it and the people you’re working with, but very quickly it all boils back down to the work itself. Which would be the same on a $12,000 movie as it would be on a $50 million movie, I presume. I don’t know, I haven’t gotten there yet.

When you first came up with the idea, when you’re first doing it, how much changed along the way to the genesis to what ends up on screen?

LOWERY: The one thing that’s always stayed the same is that shot of Casey [Affleck] walking out of the woods after breaking out of prison. That was the very first version of the script ever, which was a completely different movie, still had that shot in there. It started off because I had made this very tiny feature called St. Nick that had no dialogue and was very quiet and very subdued, and in the interest of doing something different I would do an action film next. I started to write an action movie, and that did not get finished, but the seeds of it, which involved a guy breaking out of jail, fed their way into this script. I think the first draft of it ended with everyone dying. Other than that, it’s pretty close to the initial version. All of the ideas and creative instincts are still very much in tact. It was funny, when we were shooting, I went back and looked at that first draft where everyone died at the end and I was like, “That’s not too bad.” A lot has changed and I spent a year working on it, but it’s still the same movie on a very intrinsic level.

When you attach a cast, obviously all of a sudden the voices you have on the paper -- you’re seeing those people, and they’re practicing the dialogue, and you’re seeing it a lot more. Often many directors will alter some dialogue to fit the character or the actor playing the character. How much was altered once you cast your main cast, or was not much altered?

LOWERY: Not much was altered. What I did do is if they had their own spin on it, I would be happy to hear that or let them do that. I was never precious with the words, sometimes I was, but very rarely. Usually I’d be very happy to let them riff on whatever I’d written. I do that myself. If there’s a scene that’s not working, I’d rather just figure out a new way to do it and not stick to what’s on the page or what we’ve planned out in the shooting schedule. You can’t always do that, but I love trying to build in as much flexibility as possible, both with the cast and everybody else. Saying let’s try to improve what’s on the page now that we’re translating it to a new medium.

When you showed it at Sundance to what’s being released, did you make any changes?

LOWERY: I cut about eight minutes out of it, plus two minutes out of the credits which were egregiously long. It’s ten minutes shorter altogether. I hope people who have seen both versions can’t really tell what’s different about it. I felt there was a point when I was making these changes and I showed one of my producers and he didn’t know what was different. I felt that once I got past that litmus test, we’re on the right path. Everything was working within the movie, I just thought it could be a little tighter. There’s some material we put back in. In some parts it’s longer, there’s a little bit more dialogue here and there. There’s one scene I cut out, that to this day I’m like, “Why did I cut that out? That should still be in there!” It didn’t slow things down too much, but I’ll always regret one thing or another, so I’m happy it’s just that thing.

The eight minutes that you cut: was it just little fragments of each scene, or was it a scene or two?

LOWERY: There was only one scene that got cut out, and it was the one that I’m like, “Why did I cut that out?” It was only a minute long. Everything else was just ten seconds here, twenty seconds there. The scene were Rooney’s [Mara] daughter is opening Christmas presents was four minutes long, and now it’s a minute. It’s things like that, where you get the gist of it, and that point in the movie especially -- I use it as an example a lot. You don’t miss those four minutes because there’s a lot of stuff happening at that particular point in the movie.

You’re an editor also. I’m sure you’ve killed a lot of babies along the way. When were you cutting for Sundance, was it a rush to get it in, and then you showed it to the audience and it was like, “Oh, I see where it’s not working now” or “I see where I could do better?”

LOWERY: As an editor, in my head I was prepared for all the pitfalls I might have working on this film. I was perhaps at first too egregious about killing the darlings and murdering those babies, because I was just like, “Oh, this doesn’t work. Cut it out, cut it out, cut it out, cut it out.” I was cutting things left and right, and the editors I was working with were like, “Hold on, we just haven’t gotten it right yet! You don’t need to cut it out!” I was like, “You’re right.” We were down to the wire. We were shooting in October still, and we showed a cut to Sundance in the very beginning of November and got in. We found out we got in at Thanksgiving, and then realized we still had a lot to do. We were definitely down to the wire, trying to get it done. We cut our sound mix in half to have more time in the editing room, and because we did that we knew we would go back to our sound mix afterwards and reopen the movie and that we would have a chance to address we felt like we might want to address as far as the edit goes. Watching it at the Echols for the first time was really the first time we saw it with an audience. We did two friends and family screenings just to see it projected while we were editing. The Echols was the first time to really watch it. You instantly see things, you read the room, you see how things are going, you see things you maybe want to tweak or change. Then I spent about two months just not looking at it at all, and that was really helpful as well, because in that time I could digest those feelings and get over and take some time away from the movie, which I’ve not done at all since before we started shooting. Then go back and reassess things and see how they look, and at that point you start to rework with it and dig back into the movie, and find the things that needed to be addressed. That was really a wonderful luxury to have, to do that and have the support of IFC who had bought it were already happy with it to let me go mess with it some more. Then we got into Cannes, and once again it was a mad dash to get it done in time. We weren’t on any particular ticking clock until all of a sudden we found out that we were going to show there. It was like, crap, we got to finish this movie in a hurry again!

How long was your first cut?

LOWERY: 105 minutes, with credits. Oh wait, the very first assembly?

Yes, your first assembly.

LOWERY: The first assembly was two hours and 45 minutes. I watched it once and was like, “We gotta start over again.” We had it put together while we were shooting, and I purposefully didn’t want to look at anything while we were shooting because if I start watching footage I’m going to start directing how it’s cut, and I don’t want to worry about that right now. It was done in complete blindness, and I watch it once and threw my hands in the air, as every director probably does when they see their assemblies, and wonders what horrible thing they’ve wrought. Then you start from scratch, and then it gets goods.

How long was your first cut after that assembly, when you were starting to put it together?

LOWERY: Maybe, two-fifteen, two-twenty.

Is there a lot of stuff that you could put as an extended cut or a deleted scenes on the Blu-ray down the road, or is there some stuff that should never be seen?

LOWERY: There’s some stuff that never will be seen. It’s not that’s it bad, you’re not going to gain anything from having seen it. There’s a lot of stuff that I love that I would love for people to see, and we’re going to make sure people see it. I love what Paul Thomas Anderson did with The Master with putting out those teasers made up of footage that’s not in the movie. I’ve cut some things like that that we’ll probably put out. On the DVD, there’s a number of wonderful scenes that didn’t have a home, and I feel they would enrich the viewing experience having seen them, even if they don’t fit into the movie itself. I look forward to making those available.

Film or digital, and why.

LOWERY: I think it depends entirely on the project. Digital is my safety net. I know how to use it, how to operate those camera, it makes sense to me. Film is much more mysterious. There’s a rigor to it that I need other people to help me with. I had to sit down with the bond company and explain why we had to shoot this movie on film. It’s such an abstract at this point, because digital is so good and of such high quality that you have to speak in abstractions such as, “It really just feels right.” You’re saying, “Every single frame, the grain structure is slightly different and that means something on a very intrinsic and hard to define level.” Whereas with digital, every thing’s going to be exactly the series of ones and zeroes, and the light responds the same way in each frame. You have to decide whether or not each project needs that ephemeral quality that film at this point can provide. I love digital. There’s a movie that I’m writing right now that I have already that this is a movie I’m going to shoot in digital, but I hope the choice remains. There are some stories -- not even stories, some feelings -- that you can’t accomplish in cinema without using cellulite. I’m sure it’ll all change. I’m sure digital will advance, continue to advance. For the time being, as much as I love it, I’m not just going to embrace for every movie. I hope to embrace both.

Your opening shot has a lot of sunlight coming in behind your main characters. Were you nervous shooting that on film, because you never know what sunlights going to do. Too much sunlight comes in, you might lose -- you know what I’m saying.

LOWERY: You just trust your cinematographer. For that scene in particular, we were waiting around for two hours for him to say that the light was at the right point. We were just sitting there waiting, waiting, and then we was like, “Okay, we can shoot now.” That happened a lot. He knew where he wanted the sun to be. He had an app on his iPhone to tell where the sun was going to be at any given time on any given day, and so we planned the shoot around that. The nervousness of not knowing if it was going to turn out or if you got too much sun in the lens and if it all washed out, you trust your collaborators to know what they’re doing and they’re professional enough to not make mistakes. There’s also the excitement of if you don’t quite know. There might be a mistake, there might be something you didn’t expect, or maybe something better. Maybe it’ll flare in a really cool way. That’s fun. It’s hard to qualify that again in a budget or to a bond company by saying, “I like not seeing the dailies right away.” That’s really kind of nice. I like not knowing what we’re getting.

A lot of filmmakers want to see it right away. It’s interesting to hear the other side.

LOWERY: They’re both appealing to me. It’s a win-win situation. I edit stuff on set, that’s fun too, but there’s a strange thrill to not knowing what you’ve gotten until a few days later. To see it for the first time and see things you didn’t expect is exciting. A couple days we had one lens that was out of focus, and that’s not the kind of thing you want to find out a few days. You deal with it.

You have some great actors in this, high profile actors. How was it that you first got them attached? Obviously everyone wants to land these actors. Was it that you gave the script to an agent? Describe how you landed that and put it together.

LOWERY: An agent at William Morris read it, and he asked, “Can I sign you?” I was like, “Let’s talk about that later.” He was like, “Can I send this out to some of our actors? Aside from me wanting to go for a deal, can we try to get this to some of the actors?” He asked who I would be interested in, and I gave him a few ideas, and Casey was one of those, but for the character of Ruth, I thought that I would find an unknown actress. Then Rooney’s agent asked if we could send it to her, and that was sort of a lightning strikes moment, because The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo had just opened a few weeks prior. She was someone who I thought was a tremendous actress from the three films of hers I had seen, but I couldn’t tell you what she looked like in person or what she really looked like, because every role was so different. I was really excited about the idea. We sent the script out, I wrote a little note to each actor, and we sent it out with my short film Pioneer. I think it was the combination of that short film and the script that got them excited about it. Also, just their personalities. They all like that type of material and wanted to tell that type of story, and then conveniently had a window of opportunity in which they could all do it. It was all a serendipitous combination of right material, right time, and them taking a chance on me.

I’m sure I have to wrap up in about a second, so let me just ask you with the stuff you’re writing now, are you envisioning more indie? More Hollywood actors? What are you thinking about for the future?

LOWERY: It’s a little bit of both. You always want your movies to reach the widest audience possible. Some of the things I’m writing right now -- a great way to get things out to audience is to use actors they recognize. Right now I’m writing things with people in mind, I’m writing something I want to do with Casey again. The are other ideas I have where maybe the right approach is to go make another $30,000 movie with nobody it. It’s more personal, it’s more risky. I don’t want to spend someone else’s money on something that might never make it back. The riskier it is, the better I think it is to spend less money on it. It just depends on the movie. I really hope I’m lucky enough to continue making a living off of this, but I also don’t want to limit myself to one thing. The $12,000 movie I made before this one, the feature, I love that movie. I think it’s a great film. I had such a good time making it, and I think I would love to do another movie like that as well.