Of all the mind-bending occurrences 2019 has brought us thus far, in hindsight it may well go down as the Year of the Deepfake—when the nascent technology collided with the mainstream. Over the past ten months alone, viral deepfakes of Nancy Pelosi, Mark Zuckerberg, Jordan Peterson, and Bill Hader have been viewed by hundreds of millions—if not billions. Yet the public is only beginning to grapple with what happens when seeing is no longer believing.

Things were so much more simple (albeit still gross) in 2017 when “deepfakes” was just the pseudonym of a Redditor who figured out a relatively easy way to use artificial intelligence to quickly and semi-convincingly swap the faces of A-list celebrities onto the bodies of porn stars.

Two years later, deepfakes—a portmanteau of “deep [machine] learning” and “fakes”—has been appropriated as the catch-all noun and verb used to refer to face-swapped videos and the AI-driven algorithmic models driving their creation, many times at the hands of amateurs and hobbyists.

Deepfakes fall along a wide spectrum that stretches from benign “remixed” entertainment in which new actors are swapped into the starring roles of classic films to sinister propaganda and disinformation campaigns created by shadowy entities. Deepfakes sit at the crossroads of a new audiovisual paradigm, with jaw-dropping legal, ethical, and sociopolitical implications in every direction.

Within five years, deepfakes will have advanced to the point that it will not only be possible but probable we’ll be watching the likes of Marilyn Monroe co-starring opposite Heath Ledger in entirely original feature films. This is according to professional VFX artists and amateur deepfake enthusiasts alike, such as the hobbyist deepfaker known as Sham00k (who, like most deepfakers, prefers to be referred to by pseudonym in the context of discussing their work).

“The tech is already there,” Sham00k told me over Discord, a popular gathering point for various deepfaking communities following Reddit’s decision to shut down the original, mostly NSFW deepfakes subreddits. “As long as the source material is available of somebody—i.e., video/photographic footage—of a certain quality, then it's entirely possible right now.”

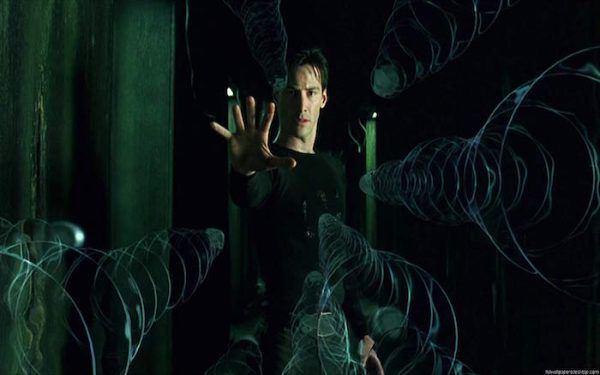

While it’s not quite that black-and-white in term of the tech being there, one look at Sham00k’s breakout deepfake—“If Will Smith Had Said Yes to the Matrix Instead of Keanu Reeves”—and it’s clear that the hobbyist deepfakes community is serious about creating entertaining content that both educates the public on the tech while pushing the technology forward one face-swap at a time.

For Sham00k, whose relevant qualifications are just two years of university-level computer science classes, he’s only been familiar with deepfaking models and scripts for the better part of a year. And, even then, he found the first software he stumbled on, Fakeapp, to be user-unfriendly.

“I think I saw a suggested video on YouTube by derpfakes,” said Sham00k, referring to one of the earliest deepfakers to go viral. “I believe it was a tutorial on how to create deepfakes. I thought it looked like an interesting challenge and that was how I got into it. It wasn't until after my first deepfake I decided to join a community of other people doing the same thing, there's only so far I could have gone without getting advice/help from other more experienced people.”

Over the past year, the deepfake community has exploded into a full-fledged digital subculture of sorts. Much of the attention has been centered on the prolific deepfaker known as Ctrl Shift Face. He’s the creator of the aforementioned deepfake of Bill Hader as Arnold Schwarzenegger, along with deepfakes of Jim Carrey as Jack Nicholson in The Shining, Tom Cruise as Christian Bale in American Psycho, and many other actor-swapped videos that reimagine seminal moments of modern cinema with view counts in the millions. (Ctrl Shift Face failed to respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Will we one day in the near future be citing this loosely aligned and pseudonymous group of pioneers as the arbiters of a new age of cinema? Or will we be cursing them for popularizing this user-friendly tech in a way that forever alters our perception of reality? Only time will tell. For now, those at the forefront of the community seem to have drawn their own line in the sand.

“I am deepfaking for entertainment,” Sham00k said. “That is it, if somebody contacted me asking to commission something illegal/immoral I’d have to say no.”

Still, the only limitations to how advanced deepfakes can get are hardware and looming legal implications. For the estates of performers who might wish to see their famous relatives once again starring in new TV and film projects, the legal and business precedents for deepfakes are already well established thanks to the use of live “hologram” performances of Tupac and Michael Jackson from a few years back. This is why, of course, deepfakers like Sham00k must disable monetization of their YouTube videos and hope that Google continues to view what they do as parody (the law is safely on their side here—for now, at least).

“The only thing I see making deepfaking for pure nonprofit entertainment purposes difficult is copyrighting somebody’s likeness, which is already a thing,” Sham00k said. “In terms of a broader sense there won’t be any laws enacted to restrict the use/production of deepfaking. It’s too valuable a tool to large corporations for that to happen, but that’s opening another can of worms entirely.”

Before we’re watching deepfakes of James Dean or Audrey Hepburn machine-learned onto the bodies of actor-impersonators, the incorporation of deepfakes in features will be more subtle and largely relegated to supporting roles. And before that, apparently, we will be watching CGI composites of said actors like the just-announced Vietnam action film Finding Jack which features a resurrected James Dean in a supporting role. While Finding Jack does not appear to be relying on deep fake tech, at some point the technologies will converge and be interchangeable in ways that compliment one another. And we may not even notice the shift.

For example, deepfaking will drastically reduce the cost of digital wizardry that resurrected Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin and allowed us to revisit Carrie Fisher as a 20-year-old Princess Leia in Rogue One. Also, digital de-aging techniques of various players in the Marvel Cinematic Universe and The Irishman will become cheap enough to use in films with less than blockbuster budgets, with up-and-coming actors competing for roles with stars brought back from the dead or to their youthful prime.

Perhaps even sooner, however, the same AIs underpinning deepfakes will be used for much more nefarious purposes to create forged digital realities in which politicians and other public figures say and do things that never transpired in real life. Anyone with even a passing understanding of the technology agrees this is inevitable, if it hasn’t already happened.

Michael Accettura, a compositor at Vancouver’s CVD VFX studio, has patched together multi-disciplinary visual effects into seamless wholes for Stranger Things, Suicide Squad, Batman v Superman, Kong: Skull Island, and many other triumphs of digital sleight-of-eye.

Accettura has embraced the amateur deepfaking community in his exploration of how the tech can be applied to the professional VFX industry in ways that could help his teams avoid uncanny valley.

“Uncanny valley is a bad result when recreating stuff like a human face,” Accettura said. “It’s when everything looks right but it feels wrong because of abnormalities and missed micro-details, which clash with whats intuitive. Deepfakes would help recreate these movements in order to break away from the uncanny valley and further achieve photo real effects.”

Like many with even a passing interest in visual effects and CGI, Accettura became peripherally aware of deepfakes a few years ago alongside the controversy surrounding the pornographic exploitation of the technology. But it was only a few months ago that he took a deep dive into learning the tech himself.

“Now I find myself in several different communities hanging out with developers, programmers, and everyone who is trying to push it further,” Accettura said. “Some studios are already looking into [deepfakes], but they’re running into the limitations of it already. It’s lots of money at this level to even try things, so I feel that the first ripples are just coming out and it’s cool to see.”

In what may be the first instance of a major studio pushing deepfaking tech out into the wild, a trailer for Gemini Man ()—in which a hitman played by a contemporary Will Smith faces off against a younger, faster cloned version of himself—appeared on the star’s YouTube channel in late July.

While the film itself relies solely on the “traditional” VFX techniques we’ve come to know and love in recent years, this special Gemini Man trailer is bookended by promotional footage featuring grainy, blipped-out analog television footage of 1989-era Will Smith as the Fresh Prince of Bel Air. The camcorder-style footage has been deepfaked to depict the Fresh Prince giving “Old Will” sage advice as to what he should be doing 30 years into the future and is credited to Collin Frend, aka birbfakes.

“You should come back to Philly a lot and, you know, visit people,” says the deepfaked Will Smith in the introduction to the trailer. “But also you should do a movie, like, called Gemini Man, and you should, like, release the trailer so people can see it. So that’s my advice for the future.”

With all of the excitement surrounding deepfakes and its collision with the mainstream, Accettura is careful not to lose sight of its less-than-wholesome origins at the murky intersection of AI and porno—particularly because far more destructive applications of the tech are already being workshopped and counter-measured behind closed doors.

“There are [facial recognition] AIs far beyond the models and deep learning approaches that we currently find publicly,” Accettura said of the most advanced tier of the technology that makes deepfakes possible. “But those ones are usually locked down with the governments and university and such. For instance, they might be using AI to train AI and it’s just exponentially at that point.”

Why are nation states and their institutions of higher learning devoting such secretive resources to understanding how deepfakes work? Aside from digital forgery being used for propaganda and disinformation, the abuse of facial recognition technology by authoritarian countries like China are already imminent threats to human rights. On a lesser level, the irresistible temptation of easy-to-use faceswapping apps seem to be packed with malware and viruses originating from places like Russia.

What may seem like a sudden interest in deepfakes has, like the widespread adoption of many emerging technologies, been years in the making. While several models and scripting packages that allowed relative novices to create deepfakes have been around since at least mid-2017, it was the confluence of events surrounding a user-friendly open-source package called DeepFaceLab that sparked the exponential growth of deepfakes in 2019.

DeepFaceLab was put together by an elusive and purportedly (but unconfirmed) Russian national known only as Iperov. When reached via email for comment on his impetus and purpose for creating DeepFaceLab, Iperov didn’t respond beyond: [sic] “sry I have no time for that.”

The lore surrounding Iperov is cryptic as the origins of the original deepfake algorithms themselves. “I could be entirely wrong here, but from my understanding he took on the tech and developments of previous people and made into one that just sort of worked, Accettura said. “With the advancements of peoples work and addition of user friendliness, more people were able to get involved. The timing of this combined with people’s interest in the technology was the mix needed for it all to happen.”

Like many operators in the somewhat shrouded (and certainly layered) world of deepfakery, Iperov is known to be prickly yet ultimately good-natured. Everyone in the deepfakes community seems to agree that his presence looms large over the current generation of deepfakes.

DeepFaceLab is the engine that has driven interest to this unprecedented level that has demanded an immense amount of respect and resulted in fear of how this sort of tech—which literally gets better and smarter by the day, as its AI models eat more and more images of faces—can be abused by anyone and everyone.

“The greatest threat with any of this would be the mass automation of less than morally correct content where it doesn’t even need a person anymore,” Accettura said, referring to a method of deepfaking that can create unholy amalgams of faces that do not actually exist in the real world. “It scrapes from the internet, throws it together, and publicizes it. If there were ever some, like, sci-fi level baboonery it could be: ‘Oh can you trust this evidence in court because it could be fake?’”

While most deepfakers who aren’t actively attempting to mislead the public agree that more must be done to keep malicious actors in check, the concern surrounding the misuse of deepfakes in the wild seems reactionary to some.

“I feel like there's a huge amount of fear-mongering surrounding deepfakes, but was it not the same when CGI started to blow up?” Sham00k said. “There are and all ways will be ‘artifacts,’ or clues in deepfakes that give them away. You’ll never be able to create a 100 percent undetectable deepfake.”

Unlike metadata embedded in digital photography that can be easily checked to determined whether a digital photo has been altered, deepfakes cannot be proven false from the underlying data alone. Discernibly fake or not on a technical level, like “fake news” the real threat of deepfakes doesn’t (yet) stem from the accuracy or convincingness of the underlying information. The danger lies in how new forms of disinformation are carefully crafted and distributed to influence belief on a psychographic and highly targeted level.

“You could put out a deepfake right now and it doesn’t even have to be at a professional level,” Accettura said. “It’s just the way our world works now is that you could put out a video and it will spread like fire, and people won’t care if it’s real or fake.”

Thankfully, at the moment, it seems that the “good guys” (a highly debatable label, given the context) are winning by staying two steps ahead of the algorithmic curve. In September, Facebook announced the Deepfake Detection Challenge, a multimillion-dollar partnership with Microsoft, MIT, the University of Oxford, and others with the goal of producing “technology that everyone can use to better detect when AI has been used to alter a video in order to mislead the viewer.”

For the time being, however, the ability to re-cast movie stars in films in which they never starred in and the seedy underbelly of digitally forged propaganda seem to be destined to become ever more intertwined.

This summer Corridor Digital, a Los Angeles-based production studio known for its massively viral and hilariously subversive online videos, was contacted by protesters in Hong Kong who asked for Corridor’s assistance in determining whether a video of the leader of their government was the real deal.

“One of the Hong Kong protestors reached out to us, recalled Corridor Digital business manager and producer Christian Fergerstrom. “And they said, ‘Hey can you guys lend us your expertise and let us know if this video of Chief Executive Carrie Lam speaking is deepfaked? We’re not sure if we trust it, you guys know what you’re talking about.’ Our final result [of the analysis] was that it wasn’t deepfaked. If you’re really looking at how the throat moves when somebody’s talking, you can kind of tell.”

One of the reasons the Hong Kong protestor reached out to Corridor Digital was because of their recent and highly viral deepfaked short-form videos. Unlike the community centered around Ctrl Shift Face and his cohorts, the deepfakes Corridor has achieved are based on original productions and not preexisting footage.

Corridor is responsible for this deepfake in which Keanu Reeves stops an armed robbery at a convenience store and an earlier deepfake in which Tom Cruise appears to visit the company’s offices.

With this pair of videos, Corridor is one of the few studios in the world actively producing original, scripted deepfakes. The production apparatus behind what they’re doing is prototypical of how Hollywood might approach deepfakes in the future.

For the Tom Cruise video, Corridor hired professional Tom Cruise impersonator Evan Ferrante, aka Not Tom Cruise, for a performance that was later deepfaked with Tom Cruise’s face. With an impersonator of Ferrante’s caliber—who sounds exactly like Tom Cruise—creating a convincing illusion of the genuine article visiting Corridor’s offices became infinitely more achievable.

Since then, Ferrante has been tapped by Ctrl Shift Face and Collider’s very own Frank Lucatuarto to perform in an alternative-universe reimagining of what Iron Man would be like if Cruise were cast instead of Robert Downey Jr.

“I consider it cautionary entertainment,” Ferrante said about his deepfake work. “A lot of people are waking up to what deepfakes are, and that’s a good thing. I think it’s important that we see more and more of it, so people know what to expect when it’s used in a political manifestation or machine—because that’s scary. I think anything done in the entertainment space is a good thing and should be done by these technicians.”

When Corridor first contacted Ferrante this summer about participating in their video he had never heard of deepfakes but was nonetheless enthusiastic about the experiment. From there, it was just a matter of blocking the correct angles and relying on Ferrante to nail his performance.

“When you’re in the room with Evan Ferrante and you close your eyes, it sounds like you’re in the room with Tom Cruise,” Fergerstrom said about Corridor’s work with Ferrante. “From there we just took the footage we had with Evan and scoured the internet for Tom Cruise angles—whether it’s from movies or interviews, basically you have to load up the AI system with a bunch of faces so it can work. And the longer you let it bake the better it can find the matches between those two faces and make it work.”

Ferrante said he thinks that while deepfake tech will have implications for professional actors, they’ll just have to adapt.

“Actors, I would say, generally speaking, are a difficult breed,” Ferrante said. “If there’s a way to avoid working with actors, Hollywood will figure out how to do so. I think it’s inevitable, especially when it gets so good the quality of the visual effects and vocal work. There’s also going to be loopholes… I can see if it’s a Frankensteined version of Tom Hanks or Tom Cruise or Christian Slater or somebody where they’re taking pieces of them and making [new] actors of them.”

Speaking of loopholes, inevitably Hollywood, lawmakers, and hostile actors looking to spread disinformation will continue to try to outrun one another when it comes to deepfake tech.

Although Hollywood wasn’t happy when New York, Virginia, or even Congress took passes at laws regarding deepfakes, it seems that Texas’s persistence has become a legislature bellwether regarding AI-forged videos.

In early October California passed AB 730, making it illegal to create or distribute videos in which the face or speech of a candidate has been manipulated to discredit them within 60 days of an election. Also signed into law was a second bill, AB 602, which allows Californians to sue deepfakers who incorporate their image into pornography.

“Drafting AB 730 was more difficult because of the First Amendment protections afforded to political speech,” said California Assemblymember Marc Berman and principal author of both of deepfake bills. “Additionally, we had to choose our words very carefully to articulate the kinds of editing/manipulation we intended the bill to regulate, while avoiding unintentionally capturing images and recordings that, for example, do not appear to be authentic or that, most simply, could not or would not deceive a voter into voting for or against a candidate. As it relates to AB 602, there was more consensus about what constitutes sexual conduct.”

How the definitions of terms like “discredit” and “image and likeness” may be interpreted in the legal context of deepfakes may mean we are already sliding down a particularly slippery slope. At the very least, it’s uncharted terrain.

“Voters should have a right to know when video, audio, and images that they are being shown to try to influence their vote in an upcoming election have been manipulated and do not represent reality,” Berman said.

One thing’s for sure: the entertainment industry will not sleep on this technology, and they may also be at the forefront of developing ways to detect it in the wild that could save us from an international incident sparked by a digital forgery.

Still, the takeaway is that the integration of deepfake tech into feature films are mostly a plus for the visual effects industry.

“I don’t think it will ever replace or remove the current positions,” Accettura said. “The next step after introducing it to smaller-level productions would be the combination of the two—you’d work with them together. You’d try to introduce the AI in situations that are far away or small or not as detailed—easier to approach—and you’d still need the full VFX team for the hero ones. It would work together; you’d maybe take patches of AI, and in places it doesn’t work you’d patch from a constructed CG face. If anything you’d make more jobs because you’re adding a whole other department into the scene.”