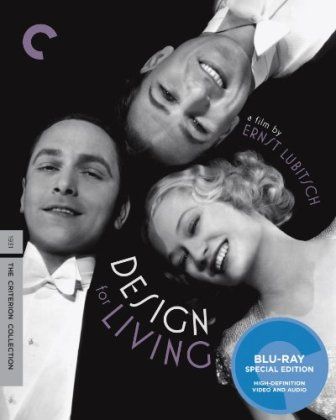

When those of us who have grown up watching modern cinema view pre-Production Code movies, it can be easy for us to ask, “What’s the big deal?” By today’s standards, much of what was considered “morally questionable” enough to spur the introduction of the Code in the 1920s would be considered laughably tame. Every now and then, however, one has the opportunity to watch a pre-Code film that causes one to understand (with a nod to differing historical norms, of course) how certain movies could indeed generate such uproar. Ernst Lubitsch’s Design for Living (based on Noel Coward’s play of the same name) is just such a film. Hit the jump for our review of the Criterion Blu-ray for Design for Living.

It is not that Design for Living is filled with nudity; there is none. Or foul language; nary a dirty word is to be had--although there is a certain frankness in the use of such ordinary, non-obscene words as “sex” (in terms of the act, not gender) that one suspects to be far more representative of the language uttered by everyday Americans than that of most intra-Code movies.

No, Design for Living’s taboos are purely of the situational.

Gilda Farrell (Miriam Hopkins) meets struggling playwright Tom Chambers (Frederic March) and struggling artist George Curtis (Gary Cooper) on a train to Paris. Tom and George are roommates, and both fall in love with Gilda—who falls in love with both of them. When Tom and George realize that she is seeing both of them, they agree to forget her, a promise that quickly vaporizes when she comes to their apartment. Unable to choose between them herself, Gilda makes a pact to be their friend and a muse of sorts to advance their careers—with no more sex.

Gilda is quickly successful in connecting a producer with Tom, who moves to London to oversee the launch of his play. While away, Gilda and George rekindle their romance to Tom’s chagrin. When he runs into Gilda’s stuffy boss Max Plunkett (Edward Everett Horton), himself a failed Gilda suitor, at a performance of his play, he learns that George has also achieved success. Tom returns to Paris, and as luck would have it, George is in Nice. That night Tom and Gilda sleep together.

George returns early and realizes what has happened. Once again unable to make a choice, Gilda runs away and marries Max, of all people. Back in America, Max hosts a party for some of his clients, an event at which Gilda is miserable. Tom and George crash the party. Max finds the three of them laughing on her bed, and Gilda announces she is leaving him. She, Tom and George decide to return to Paris and their unique living arrangement.

Sex (admittedly not shown, but discussed quite frankly), marital infidelity, and, most scandalous of all, ménage á trois, compounded by the fact that the character in the middle of these unusual relationships being a woman…Design for Living is a perfect example of just how racy pre-Code Hollywood actually was.

It should be noted, however, that, for all of the above, Gilda is never portrayed as a slut. She honestly loves both George and Tom (who themselves share a non-sexual friend love) and is very much their equal in their relationships. In perhaps the film’s most memorable line of dialogue—and all of Ben Hecht’s script glides off Hopkins, March and Cooper’s adept tongues onto the screen—Gilda comments on the differences between how men and women approach love and what society finds appropriate for each gender…and that she, in this complex case, loves like a man.

The Criterion Collection transfer is gorgeous, only marred by a projector line that appears for a short period later in the film. Sound quality—often (and understandably) the weak point of many early sound-era DVDs—is stellar. Although supplements are few, those extras included are excellent additions. They include the brief but humorous “The Clerk”, Lubitsch’s segment of the 1932 omnibus If I Had a Million; selected scene commentary by William Paul; an interview with Joseph McBride on Lubitsch and Hecht’s adaptation of the play; and a 1964 British television production of the play Design for Living (introduced by Noel Coward himself). The latter, a far more literal production of Coward’s work, provides for fascinating comparison with the Lubitsch adaptation.

Athough somewhat overlooked in Lubitsch’s ouevre, Design for Living is a highly entertaining film that exemplifies how daring Hollywood could be before the specter of the Joseph Breen-era Production Code censorship raised its ugly head.