[With Guillermo del Toro’s new movie Crimson Peak opening next Friday, I decided to take a look back at the director’s filmography.]

“What is a ghost? A tragedy condemned to repeat itself time and again? An instant of pain, perhaps. Something dead which still seems to be alive. An emotion suspended in time. Like a blurred photograph. Like an insect trapped in amber.” – Dr. Casares, The Devil’s Backbone

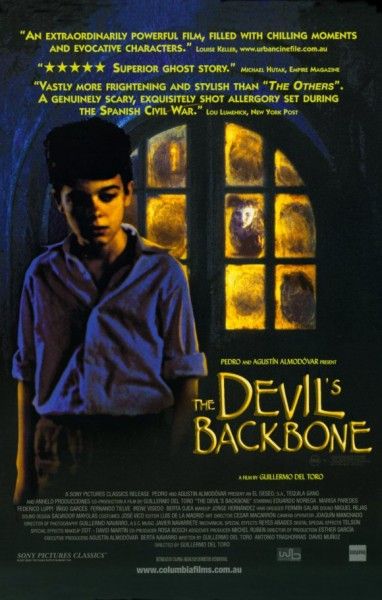

Despite the wreckage of Mimic, Guillermo del Toro was still being offered Hollywood films. Specifically, New Line Cinema wanted him for Blade II. However, he stressed that if they really wanted him, they would wait for him to make The Devil’s Backbone, a movie where all of del Toro’s talent comes together to tell a story of love and tragedy that’s perfectly mixed together.

The Devil’s Backbone is a beautifully told ghost story where the real ghost isn’t Santi (Junio Valverde) the dead boy wandering the grounds of an orphanage during the Spanish Civil War. Everyone is in his or her own personal purgatory as well as the purgatory of war just beyond the horizon. The unexploded bomb in the middle of the orphanage courtyard is a constant reminder that they’re all on borrowed time, and death surrounds them. It’s a story about broken people trapped by their circumstances, and the sadness and loss that pervade their situations. And yet it never feels overbearing because del Toro cleverly colored it with a supernatural flourish and put charming child actors at the forefront.

It’s a “ghost story”, but del Toro knew not to lean too heavily on the particulars of the supernatural, and instead focused on the human element. We follow Carlos (Fernando Tielve), an orphan who doesn’t even know how much of an orphan he truly is (he thinks his father, who fought for the Leftists, is still alive). Abandoned by his tutor at the orphanage, it’s not long before Carlos starts seeing the ghost, who the others call “the one who sighs”, and if del Toro had kept a fixed position on his young protagonist, The Devil’s Backbone would have been perfectly serviceable ghost story. It would be a gorgeous film, but it would lack the depth and nuance of expanding the story to the adult characters.

Where the story gets its richness is in showing how the adults—the ones who are supposed to have the maturity to take care of the young boys—are as deeply screwed up as their wards. Devil’s Backbone has a plot, but it’s not really a plot-driven film beyond the mystery of who killed Santi and why. Far more energy is put into the complicated web of relationships between Dr. Casares (Federico Luppi), the headmistress Carmen (Marisa Paredes), and the caretaker Jacinto (Eduardo Noriega).

These three characters could each fit Casares’ musing about what it means to be a “ghost”. They’re all stuck in their old relationships, nursing old wounds. Carmen is bitter that she now bears the responsibility of carrying on the cause even though her husband, who was the true “revolutionary”, is dead. Jacinto is the “sad little prince” who believes he’s entitled to a kingdom. And Casares pines for Carmen, but she will never love him back. It all comes right up to the line of being a soap opera, but because del Toro is so earnest and never plays it for melodrama, the aching honesty works.

The Devil’s Backbone counts among del Toro’s best because while his love of monsters may serve as a hook, it’s his earnestness and adoration for characters that have made for his best movies. That earnestness sells the moment where Casares recites a love poem to Carmen, the love of his life, while she dies. It’s a moment that could have come across as incredibly cheesy if del Toro didn’t have total conviction in the storytelling. Take away the director’s earnestness, and you just have a very enthusiastic designer.

While The Devil’s Backbone may not be as ornate as the director’s later pictures, the framing and design are just as impeccable as any of his studio films. There may only be one supernatural element—the ghost—but del Toro puts as much energy into the design as anything else he does. Depicting Santi’s head wound as constantly bleeding upwards as if he’s underwater stresses the “trapped in amber” description from the opening narration. It’s horrific, but it’s also thematically relevant, which is one of the many reasons Devil’s Backbone transcends del Toro’s previous films.

I don’t want to say that Cronos or Mimic are dishonest movies, but they’re compromised. Cronos is hurt by the director’s lack of experience, and interfering producers undermined Mimic. They’re movies that didn’t fully realize the director’s vision, and Devil’s Backbone feels like the first time we truly get that from del Toro. While he’s typically associated with fanciful monsters, it’s really more about wearing his bleeding heart on his sleeve.

While it can be argued that Pan’s Labyrinth is the director’s most “complete” film since it indulges the fantastical side that Devil’s Backbone largely leaves behind, I see them more as companion films rather than separate pieces in his evolution. The Devil’s Backbone just keeps its supernatural element tied into a thematic level. Casares’ opening narration tells us that we’re watching an all-too-human ghost story, so we don’t need literal monsters. The figurative ones we face daily are powerful enough.

Through The Devil’s Backbone, we see the crippling emotions of jealousy and fear spread throughout the orphanage, and it’s clear that while the ghost may be physically scary, he’s never as fearsome as Jacinto, a man who believes he’s entitled to riches and is willing to do anything to get them. Jacinto comes right up to the line of a moustache-twirling villain, but del Toro goes out of his way to make sure that there’s some ounce of relatable humanity in the character because it’s this failed humanity that interests del Toro.

Even though there’s a fleeting moment of “justice” by having the kids kill Jacinto, the movie ends on a melancholy note, and that melancholy is where del Toro ultimately lives even though he can’t resist his odd, deeply twisted touches (notably that the “limbo juice” holding preserved fetuses is being sold to the townspeople for erectile dysfunction). Both Pan’s Labyrinth and Devil’s Backbone have young protagonists, but Devil’s Backbone, far more than the fairy tale trappings of Pan’s Labyrinth, has a sorrowful view of human history and humanity as opposed to individuals. We’re all “insects trapped in amber” and while the surviving orphans begin with a walk to places unknown, they’ll likely arrive to the same kind of suffering—the same jealousies, regrets, and fears—we all do. The Devil’s Backbone places all of us in a living purgatory with only brief flickers of grace.

Following this massive leap forward not only as storyteller but also as a filmmaker (The Devil’s Backbone is a technically stunning film), del Toro stayed true to his word and would now move to lighter territory with the Daywalker.

Tomorrow: Blade II

Other Entries: