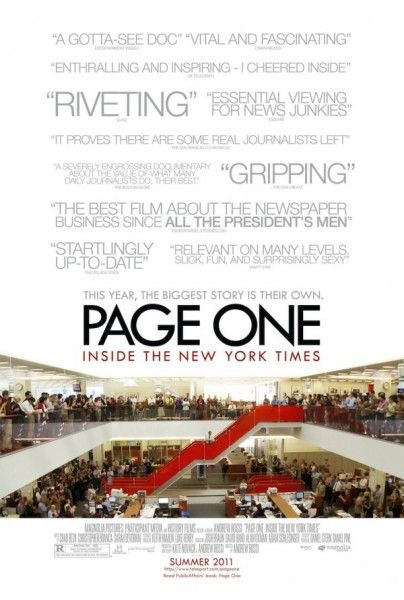

In the tradition of great fly-on-the-wall documentaries, Page One: Inside The New York Times deftly gains unprecedented access to The New York Times newsroom and the inner workings of the Media Desk. With the Internet surpassing print as our main news source and newspapers all over the country going bankrupt, Page One chronicles the transformation of the media industry at its time of greatest turmoil. The result is an exhilarating view into a world where Old School values are colliding – and sometimes converging – with a new future.

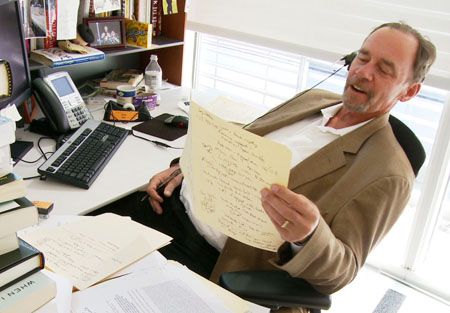

We sat down with filmmaker Andrew Rossi at a roundtable interview to talk about his new documentary. He discussed how he set about tracking stories with reporters David Carr and Brian Stelter and Media Editor Bruce Headlam on a day-to-day basis to capture the private debates and conversations that lie behind the making of the news. He also discussed the game-changing emergence of WikiLeaks and his interest in doing a documentary on the inner workings of the intelligence community.

Q: If the model for journalism that you portray in the film could exist online, would we still need to have a physical paper?

Andrew Rossi: My feeling is that the physical newspaper is almost irrelevant to the delivery of information of quality journalism. The point is really about having editors and writers truthsquad what’s out there, have boots on the ground in various places where the news is taking place and then have that processed in a manner that is intelligible for people to read on a daily basis. The biggest argument I think about keeping the page format has been the serendipity of opening the newspaper and forcing yourself to look at different things because you’re getting to the story on A11 and you’re passing through pages 5, 6 and 7 which have great stuff. I actually think that sources like Twitter have almost replaced that serendipitous function because you have a Twitter stream of people who you trust and who are curating the news for you and providing links to stories. So that’s become a new media form of seeing stories that you wouldn’t necessarily navigate to as a destination. But there’s a tremendously huge caveat to that position which is the fact that newspapers still allow for, as in the case of The New York Times, advertisement on the top of A3 from Tiffanys for which Tiffanys will every day pay tremendous amounts of money. And it is that money from the advertising that exists in the newspaper that keeps alive the whole news gathering function and the boots on the ground all over the place. So, until publishers are able to monetize their information online in the same way that they are in the newspaper, the newspaper is actually extremely important. There’s just this wrenching period of transformation now in which publishers and readers are both staring each other down and saying who’s going to flinch first or how’s this all going to work because readers somehow have been habituated into thinking that information should be free online. It’s not necessarily the case that a paywall is the right way to go, you know, like charging for news online. It’s unclear but something has to give. I think “Page One” hopes to enter that moment and that sort of void of standoff and provide viewers and readers with an ability to see what goes on behind those walls in a place like The Times, and it could be The Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post. It could be Reuters, AP, the LA Times. It could be really any place that great quality journalism is being done. It just so happens that in this case it’s at The Times. But people should know how difficult it is for those stories to come alive. Sometimes an entire day is spent with several people deciding to not run a story as we see in the film when they’re reporting about the end of the war in Iraq.

Q: Do you think public trust is being eroded in the newspapers?

AR: Absolutely. The fact is that there has been a really impactful sort of erosion of authority in some of these huge newspapers. “Page One” really goes to the core of that argument and deals with the failures and the run up to the war in Iraq, the reporting by Judy Miller and Michael Gordon that erroneously reported weapons of mass destruction existing in Iraq, the Jason Blair scandal. And it does that because it is important for people to not necessarily trust as the gospel what they read in The Times. The tagline for the film is “Consider the source.” That’s part of the Social Action Campaign and that’s really relevant, not just to the idea of oh well, if I read something online, is it true or is it not? But it’s also if you read it in The New York Times, you need to … The tools of the insurgency which allow us to produce web video and have our presence on line with blogs and stuff also allow us to truthsquad the information that we see in places as august as The New York Times. So I think that’s a very valid point. There are no sacred cows anymore.

Q: Can you talk a little about the process of making a documentary that is also a compelling piece of entertainment and how it took shape?

AR: Well that’s a fabulous question that I could go on and on about. I constructed the film with my co-writer, Kate Novack, who’s also a producer on the film, and with our editors, Chad Beck who was an editor on “Inside Job,” Sarah Devorkan who worked on the Stephin Merritt film, and Chris Branca who is a new editor. The guiding principles that Kate and I use when we storytell are very much informed by Robert McKee who looks at story structure from the perspective of Greek mythology and also scene structure in terms of plusses and minuses, these valences where you’re really engaging the viewer on an emotional level and so things pop and then things sort of subside and pop and subside. So, we try to do that cinematically with ideas and with scenes. There’ll be one scene that’s Brian Stelter watching a video of reporters being gunned down in Bagdad, the Reuters journalists who were killed in Bagdad and WikiLeaks leaked that story. There’s a very high energy to that story and thematically it’s all about the collision of old and new media. And then, there will be another scene that has a different type of valence, a more subdued one in which maybe we’re seeing David (Carr) report on the Tribune Company story, a story that he took the entire summer to report, and there were many moments where there wasn’t a ton of hugely exciting stuff going on but it provides an opportunity to see the more mundane or prosaic aspects of being a journalist. And so, we did not go with a chronological structure because we wanted to allow for that kind of cinematic journey. But that being said, we also tried to make sure that there was a fidelity to what had really happened and that it was accurate.

Q: What was it about David Carr that inspired you and made him the focus of your documentary?

AR: You spoke to him so you know. David just will not take BS from anybody and he has lived this life that has taken him to every high and low possible and so he’s come out on the other side. He’s also got an incredible sense of humor. He’s really just so insightful and I think a brilliant writer and he’s like the perfect Virgil through all these really heady ideas and intellectual debates where you have a lot of new media apostles proselytizing as if they know everything and sort of yelling at you. And then sometimes you have the risk of people who are just romantically attached to the old, traditional ways of doing things. David is like this perfect bridge between those two worlds. He’s somebody who came up through the alternative weekly culture of journalism in Minneapolis but now has over 300,000 Twitter followers. Somehow he strikes a chord with people when they watch online videos of him. He’s like a Max Headroom for today. So he just seemed like the perfect person to guide the film.

Q: Is there something about putting print people on camera? Do you have to tell them to not act and just be natural?

AR: My process is very low-fi in a way, meaning that I shoot all by myself with a shotgun mic on my camera and a radio mic on the subject. I don’t have any people with lights. There’s no field producers watching us. It’s just me and the subject. Typically what I do is there are several days of shooting in which nothing is happening but people are getting used to me being in their shadow and that’s great, because then when things really do perk up or flare up, there’s a comfort level that’s already been established.

Q: One of the things I particularly appreciated about the film is how it shows the importance of the role of the editor in traditional journalism when a lot of what passes for journalism online is unvetted and sometimes inaccurate or intentionally false. What about that sense of equivalence between news from the mainstream media versus online sources?

AR: I think that’s absolutely right. And I also think that a lot of the online sources don’t necessarily have, like I said, boots on the ground in far flung places. Just this week, Brian Stelter was covering the tornadoes that happened in Kansas and Joplin, Missouri. He’s someone who covers Media but the National Desk needed help and so he went down there and he was tweeting all about it and wrote this huge A1 story about it. All that information – someone has to go down there and has to have the insurance and has to have the office back in New York that’s taking in all the information and creating the story with him and then it gets amplified in videos on TimesCast. The details in those stories make their way to Brian Williams’ broadcast. Anderson Cooper was there too so CNN also has the resources to do that kind of work. But anyway, if we look at… not to name names but let’s say like the Huffington Post, that is a real aggregation website. I guess that’s really what it is, is that a lot of us get our news from aggregation websites and don’t realize that that original information is getting sourced in different places. That’s the whole idea of “Consider the source.” Just because you read it in a place that’s really entertaining and has flashy headlines and what not, it’s coming from somewhere else that sort of needs your help, otherwise it might die.

Q: Would you say the idea of The New York Times and what it represents is almost as good as the reality of The New York Times?

AR: Well I must say that that’s really for viewers to decide and if that’s how you came away from the film, that’s nice to hear because in my heart of hearts, after spending 14 months there, that’s also what I came to conclude. But when I started, I really disabused myself of any sort of preconceptions of thinking that The Times is some sort of vaunted, great institution. The one thing I did know is that their mandate, their brand, is premised on this idea of producing quality journalism, original reporting, not being a tabloid, not being an opinion-driven publication. But it was through seeing what they do that I came to really respect that form of journalism and know more about it. Again, that’s really what I hope viewers see.

Q: What about WikiLeaks? David Carr made a point of saying that everybody was in slow motion, like ‘What is this thing?,’ but that you recognized right away the energy of that moment. Can you talk about how it hit you?

AR: I don’t know what it was but it just hit me, like I had a pit in my stomach that whole day when Brian Stelter was watching the video of the Reuters journalists getting gunned down in Bagdad, and Bruce Headlam, the editor, was so engaged, inspired and talking about this collision of old media and new media and I just knew immediately. As a documentary filmmaker, there was over 250 hours of documentary footage. Sometimes you’re sitting there and you know that you’re getting coverage. You’re getting shots. Let me get a shot of the phone because at some point we’ll need an insert of a phone. But, at that moment, I knew that everything, a lot of it, was going to make it into the film just because I think primarily the visceral nature of that video is something that speaks volumes. But, of course, I didn’t realize that then The New York Times would become a collaborator. It’s very hard to parse the exact, correct language to describe the relationship between The New York Times and WikiLeaks as it evolved with the Afghan War Logs and the Iraq War Logs and then the State Secrets that came out like the rest of the year. The New York Times got some of their hugest scoops from information that leaked from WikiLeaks. So it turned out to be a pivotal day because it was in that moment, as David was saying, everybody was sort of in slow motion. People couldn’t understand whether WikiLeaks was just an advocacy group or a legitimate publisher and how could they occupy both spaces at once which they do, and that’s just part of the hybrid future in which we live now, that people have agendas but they also have information and they have leverage to get their information out there because they can put it online. So this very awkward dance took place that whole summer and then into the fall between Julian Assange and Bill Keller and Alan Rusbridger at The Guardian. I think that will prove to be, when we look back 20 years from now at the evolution of journalism, I feel like that’s going to be a huge moment, either as a metaphorical moment, also just the information. Obviously, the Arab Spring is being informed by many different factors. It’s in the ether. It’s part of the conversation and so it was really great to capture that.

Q: Did you ever feel at any time that The Times might want to manipulate what you used and didn’t use? Was there anything at the management level that suggested they were a little wary of a documentarian coming in and looking over the shoulder of the Media Newsroom, especially after the Judith Miller and Jason Blair scandals?

AR: The Times had no editorial control over this film whatsoever. I agreed to uphold high journalistic ethics as a journalist in making the film so I presented myself as somebody who is not doing a satirical piece. It wasn’t like The Daily Show coming in and making fun of them. I didn’t have an agenda. I wanted to do a film in the tradition of cinema verite which is observational, and on that basis Bill Keller said yes, because he said “I’m proud of my journalists and I want the world to see them.” He really felt that if my motives were sincere and not skewed, that the journalists would come off the way they are and that would be fine. So I never felt any sense of being encouraged to film something or not or being manipulated in any way. I was actually really impressed with the transparency. It took six months of meetings and meetings about meetings and discussions, but once I was inside I think they realized if there was ever any inkling of that, that would be a scandal which would eclipse any conceivable thing that they could protect. They’re all earnest, sincere people doing their jobs and it was nothing more complicated than that.

Q: Based on your observations and experience over 14 months, watching their process and approach to journalism, did you see anything that supports the point of view that The New York Times is advocating from an editorial standpoint a particular view of politics or the world?

AR: The Op-Ed page and the editorial side of the paper is located literally in a different elevator bank than the Newsroom. There’s a really discrete wall between the two things. So the news gathering takes place on floors 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 and then all the opinion people are in another area. So nothing I shot had anything to do with opinion or politically oriented journalism. I can’t speak to that at all. But, as far as them as human beings, what I observed is that they are all intellectually curious and David seems to be a person who – I don’t know how he voted in the last election but he seems like a fairly liberal guy. I mean I think he probably supports gay marriage and other tenets in the Democratic Party tent. There’s something that he says too that those politics never seem to bleed into the journalism, into the reporting.

Q: Has this whetted your appetite for more coverage in this particular industry or do you want to examine something else? What are you interested in now?

AR: I love being able to gain access to worlds that are somehow considered off limits and typically, as a result of that, seem kind of impenetrable, and finding a really humanizing keyhole into them. I’d love to take a look at the education world, maybe at a university to see how the admissions process works, like let’s bring the cameras into Harvard University or something, or even in the intelligence world which has many different prongs. But both of those may be impossible. I think in every case it’s all about people, so if the right people are engaged at the right time, maybe it will happen, maybe it won’t.

Q: What are you working on next? What about WikiLeaks which kind of thrust you into the intelligence world?

AR: Those are some ideas that I have but the process of launching this film and the Social Action Campaign are really what I’m doing for now. There are already so many WikiLeaks movies. I would like to do a movie where you have this conventional wisdom that everything should be known and there should be no privacy. The world will be a better Utopian place. That’s almost like the conventional wisdom that at one point was saying “Who cares if The New York Times or The Post go out of business? New media is great.” I think it’d be fantastic to tell a story of how the intelligence community is saving lives and doing a lot of important work by keeping things secret in a way where you see what they’re doing the way you see the journalists at The Times, but it kind of makes my head hurt to think about it and how to do that.

“Page One: Inside The New York Times” opens in theaters on June 17th.