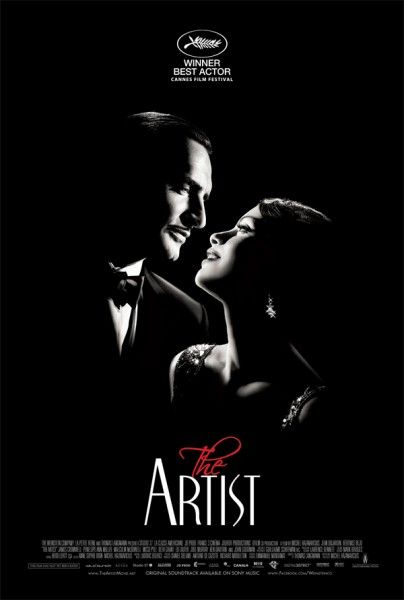

Mixing comedy, romance and melodrama to tell a story set at a pivotal moment in movie history, The Artist is itself an example of the form it celebrates: a black and white silent film that relies on images, actors and music to weave its singular spell. Having never written a silent film, Michel Hazanavicius immersed himself in the genre to gain an understanding of what did and didn’t work. Along with watching films, the director read cinema histories as well as memoirs and biographies of silent era directors, producers and stars, and he drew inspiration from the work and lives of such stars as Douglas Fairbanks, Joan Crawford, Gloria Swanson, John Gilbert and Greta Garbo.

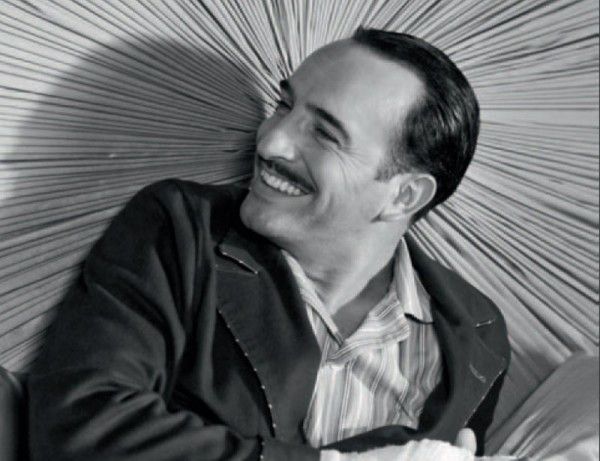

We sat down with Hazanavicius at a roundtable interview to talk about his heartfelt and entertaining valentine to classic American cinema. He told us how he immersed himself in the silent movie form, which artists from that era inspired the creative decisions he made, and why it was a moving experience for him to scout locations in Hollywood that still mirror what it looked like in the late 1920s. He also described his complicated collaboration with his composer, his thoughts on which of today’s modern actors could be successful in a silent film, and why he’s glad he didn’t have to do a silent film in 3D.

Did people think you were crazy when you said you wanted to make a silent film?

MICHEL HAZANAVICIUS: Yes, in a way. Crazy or unconscious or stubborn. But sometimes I think you have to try to do things that people don’t think are doable. I remember at the very beginning actually, the first person I had to convince was myself really because there’s a self-censorship. When everybody says ‘we don’t do silent movies anymore,’ you agree with everybody, and you say ‘yeah, you’re right.’ It was a fantasy. Actually, I met a lot of directors and most of them have that fantasy to make a silent movie because for directors it’s the purest way to tell a story. It’s about creating images that tell a story and you don’t need dialogue for that.

What about convincing the average viewer to go see a movie in black and white without dialogue?

HAZANAVICIUS: I can’t convince them. It’s not my job. The Weinstein company, it’s their job to convince people. My job was to make the movie. That’s what I did. I know what we did in France was to have the maximum screenings just to let people talk about the movie and say they enjoyed the movie. There are two kinds of audiences. There’s the ones who were in the theaters, and the ones who are outside and we want them to come inside the theater. And, it’s not the same. People inside the theaters usually, not 100 percent but most of them, enjoy the movie. Usually they come with a small negative view. In a way, they’re prepared to get bored because it’s silent and because it’s black and white. So they are much more pleased to be entertained in a way. They’re very happy when they go out. This was my job. For the other ones, I can do nothing except screen the movie and hope that they will say to their friends that it’s not so [bad].

So you’re relying on word of mouth?

HAZANAVICIUS: Yes, the only thing I can say is usually people are slightly confused. They think that silent movies are old. But, the fact is, they are old because they have been made in the ‘20s. That’s the thing that makes them old. Not the format. The format is just a format. It’s not an old format.

Anytime a movie does well, Hollywood copies it. Do you hope that if this does well they’ll make a spate of silent movies, maybe in 3D?

HAZANAVICIUS: No, no. I think Hollywood is cleverer than you think. I’m not sure they will do it. I don’t think so, but maybe I’m wrong. When we were doing the preparation of the movie, we didn’t have all the money so we were looking for all the solutions possible, and 3D was one option. All over the world there are a lot of distributors that have the equipment for 3D but they don’t have the movies really. The only source of 3D movies is Hollywood. Only Hollywood sends the 3D movies. So it was an option. They said ‘if you have a 3D movie, we’ll buy it’ because they want it. For maybe two weeks I really thought of a silent, black and white 3D movie and I thought it could be great. I imagined it as a very special image, a very new image, but fortunately, I didn’t have to do it.

Can you talk about immersing yourself in the silent movie form and how that informed the creative choices you made?

HAZANAVICIUS: First of all, it was not an idea, it’s very different. At the very beginning, it’s a desire and that’s not the same thing at all, because when you have the desire to do something, all the work you can do is a positive thing. It’s not something that you calculate. An idea is something you work on to make it work and a desire is much deeper in a way. The immersion, it’s classical, I watched a lot of movies. First of all, I had the desire for that format, and then when I was talking to people, I felt that people needed justification. Why are you doing a silent movie? Is it just for your own pleasure? I felt it was not enough for them so I realized I have to choose the subject that will make things easier for them and to tell the story of a silent actor makes sense for doing a silent movie. Then, I went to Hollywood. I put the action in Hollywood. I watched a lot of movies, maybe 100 or something close to that. I have tons of DVDs now at home. I don’t know what to do with them because they’re not useful anymore. My kids never watched them. I read a lot of autobiographies, listened to a lot of music by classical era composers like Franz Waxman, Max Steiner, Bernard Herrmann, Alfred Newman and Leonard Bernstein. I listened to only that kind of music the entire time I was writing, even at home. I looked at a lot of photos from Hollywood in the ‘20s, photographs of silent movies being filmed all over the world which are very specific and very evocative. Berenice, the lead actress, is my wife. She really followed the same path with me.

Finally, you’re right about one point, your entire way of thinking is predicted by what you’re immersed in so you know you won’t make a bad decision. You can make a bad decision but it’s still in the good sphere normally if you work well. You’re prepared to face a crew who wants to know everything and poses a hundred questions a minute, because you know you have good reflexes and can respond very quickly. I watched a lot of movies from all over the world. The Russians were very good at editing. They were specialists in editing. The Man with a Camera, if you know that movie, is incredible. I still don’t understand how it works. It’s a movie with no script, no actors and still it works. It’s really good. It’s really about editing. The Germans were much more graphical. The expressionism is much more than cinema. It was a movement with artists, painters, music and architecture, so it’s really graphic and visual. And the French were something else. I chose the American ones, more or less the last five years of the silent era, because those are the ones that aged the best in the way they tell the story. One, it’s about human beings with context. It’s a very classical story with feelings, with laughter, melodrama and it really works, the good ones— Murnau’s American movies, John Ford’s Four Sons, King Vidor’s The Crowd, or the (Josef) von Sternberg movies. You can watch it now and it still works. I mean they are really, really good pieces so this is where I tried to work.

What modern actors would you like to see do silent films?

HAZANAVICIUS: It’s not a question of the person. I’m not an expert at that, but it’s about the codes of acting. Robert DeNiro, who may be the greatest living actor, usually acts in a way which is very stone-faced, like Steve McQueen. For example, Steve McQueen, if you cut the sound, you don’t know what he’s acting really. He gives to the lines, to the text, something very special, and he’s very good. He was a great actor. But, to do a silent movie, you have to have more expressive actors. You see, John Goodman or Jean Dujardin or Berenice Bejo, they are very expressive, and when they talk, you can feel what it’s about without forcing it. I didn’t ask them to do pantomime. They didn’t mime the sequences. That’s not what I asked them to do. But I guess George Clooney would be a wonderful silent actor, and Leonardo DiCaprio is such a wonderful actor he certainly could do it.

How did you collaborate with your composer to create the tone of the film?

HAZANAVICIUS: I did it with him the same way as I did it with the other collaborators. First of all, for the composer, I gave him the references, the notes of the movie. I gave him the records of all the classical composers and also some of the great jazz tracks of that period—Duke Ellington, George Gershwin, Cole Porter. I wanted an American texture. He studied it while I was writing, and when I was shooting, he worked on that very specific sound. Actually it’s a mix of something very American and very European. There are a lot of composers who are Jewish, Eastern European composers who emigrated to Hollywood. So he worked on that. And, at the end, when I started to edit the movie, that was the most difficult part because he had the reference and he had the spirit of the music, but he had to respect the storytelling. I was in charge of the story so he had to obey me very precisely and that was very difficult for him. It was difficult for me as well because I had to say ‘from here to here, there is very light music and in the best world I would like that we don’t even notice that there’s music. Try to be very discreet. And here, there’s a conflict, I want you to mark it but not level four, let’s say level two. It’s not a huge conflict, but a small one. And then there’s a resolution, so please mark the resolution.’ He had to follow that very precisely and it was not obvious. It was also not easy because the editing process is something you’re improv-ing day after day. I gave him a narrative block that was 12 minutes, let’s say, and two months later it’s eight minutes. All the parts I gave to him, they moved, so he had to adapt his own music. It was really very challenging for him and he did a great job.

Did you find locations in Hollywood that still mirror what it looked like in 1929, 1930?

HAZANAVICIUS: I loved that part. Scouting for locations was very touching. We’ve been in very specific locations. I love the Hollywood tour, I mean, the cinema tour, The house of Peppy Miller is the real house of Mary Pickford. When George Valentin wakes up in bed, it’s the real bed of Mary Pickford. I’ve been in the office of Charlie Chaplin, the office of Harry Cohn, the studio on La Brea where Chaplin shot The Gold Rush and everything, and the theaters downtown, the Orpheum, the Los Angeles Theater, and the Bradbury Building, the Cicada restaurant, and we were in the apartments of the Cicada restaurant. We’ve been in the Douglas Fairbanks studio, the Max Sennett studio and all the houses. I don’t know if you remember Gloria Swanson’s house in Sunset Boulevard. That house has been razed. They demolished the house, but someone bought the fountain. The fountain is now in Pasadena and we went to the house and saw that fountain. That’s the only thing that survived from that house. I’m the hugest fan of Billy Wilder you can find. He’s a God to me. So, for me, it was really touching. Unfortunately, we didn’t shoot in that house, but just to see that fountain was very touching for me.

Before you thought about making this film, were you a big fan of the 1920s music, fashion and movies?

HAZANAVICIUS: Yes, but I’m not a nerd for that period. My next movie will be somewhere else in a different period. I like to shoot beautiful things. My two previous movies were one in the ‘60s, the other one in the ‘50s, and this one is in the ‘20s. This is a period that’s very cinegenic. The cars, the props, the suits, the haircuts, the dresses, everything, and it gives you pleasure to compose frames with that material. The music, I really love jazz, so for me, when you have good materials and nice things, it’s very pleasant. For this one, it was very important to do something nice for this specific movie.

Were you tempted to use old cameras from the silent film era?

HAZANAVICIUS: No, not old cameras. We used a camera that makes noises because we didn’t care about that. We didn’t try to find old cameras. That doesn’t make sense. We used some old projectors, spotlights, because they were very specific. Also, there are no more old lenses. There’s a guy at Panavision who’s a technical geek about those kinds of movies, and he did some alteration of the lens for us which gave us some distortion in the image. I used it, for example when the lead actor contemplates suicide, the shot of the gun and of the dog, there’s a small distortion. You can try to do it, but it’s not the same if you do it in post so we used that. It’s not so much about the technical aspects. It’s more about the way you conceive things. I didn’t use a Steadicam, for example, because a Steadicam shot doesn’t make sense to me in a period movie. For the crane shot, it was a very modern crane and it goes farther. When he walks out of the cinema and goes down the street and there’s a line and they’re all waiting to see Beauty Spot, when there’s a shot like this, it would be stupid to use an old camera, an old crane. It would take hours. Now we do it with remote control. The technician was really good. It’s not an easy shot to do, but with a modern crane, you get time and quality.

Are there any deleted scenes for the BluRay/DVD?

HAZANAVICIUS: Not so much I think because the first movie in the movie I shot some additional material but I edited almost all of it into the story and we are out of the sequence on the screen. The problem is I don’t have the music and also I need some special effects, a little bit, and I don’t know if it’s really interesting. Usually I’m not a big fan of showing the trash.

What will there be on the DVD/BluRay?

HAZANAVICIUS: I think there’s a very small behind-the-scenes featurette and also bloopers, silent ones. I don’t know exactly, but they’re working on it. ‘

I’m a fan of your work now. If I go to see any of your previous movies, is there anything comparable to this?

HAZANAVICIUS: I think there’s something in common with the OSS 117 movies. The big difference is there’s no irony in this one. It’s not parody. I tried to make it very simple. It’s a simple story, but to be simple, it’s very complex in the way it’s done. Usually, when you do a period movie, you just recreate what you are shooting. You don’t recreate the way you shoot it. I think I did the same thing here as I did in the OSS 117 movies. I recreated the way to shoot that period, because to me, like what I was saying about the Steadicam, there’s no sense to do a Steadicam shot in the 1920s because you have never seen the ‘20s like that. You can’t believe there was a Steadicam in the 1920s. I believe it’s a continuation of the OSS 117 in a way but without the irony.

With respect to the green aspect of production, was there anything done to reuse, recycle and reduce the carbon footprint?

HAZANAVICIUS: Yes, we did some. For example, that they gave us bottles for all the cast and crew.

They gave out canteens?

HAZANAVICIUS: Yes. You have to thank the producer, the American one. He decided to do it. I never would have. It’s not my job. I was here to make a movie, not to save trees, but I’m very happy that we did

What’s lined up for you next? Will it be something from the 1900’s?

HAZANAVICIUS: I have some things in the works but nothing concrete yet. It will be something from today’s era, I think.

The Artist is now playing.