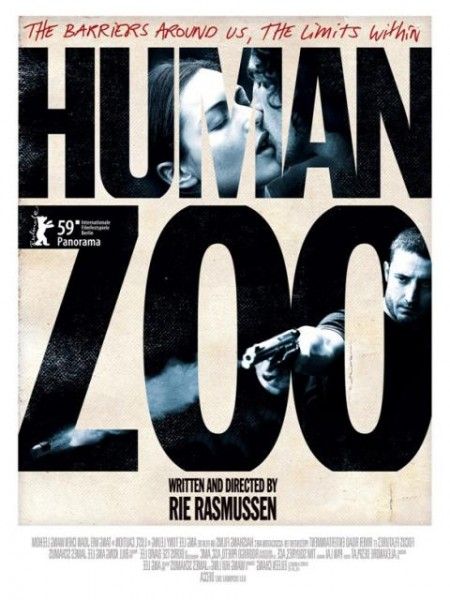

Hand picked by Quentin Tarantino to make its U.S. premiere at the New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles, starting on November 11th, Human Zoo marks the feature film debut of director Rie Rasmussen. The drama tells the story of Adria (Rasmussen), a half-Serbian and half-Albanian young woman whose past saw her in the war zone of an as yet undisputed Serbian Kosovo. Surrounded by violence and living with a sociopathic man, that life is in stark contrast to her life in present-day Marseille, as an illegal immigrant. The film takes audiences on Adria’s intense life journey, while illustrating the compromises we sometimes have to make, in order to survive.

During a recent exclusive interview with Collider, filmmaker/actress/model Rie Rasmussen talked about how the history of the development of this story, her decision to star in the film (as well as writing and directing it) because she knew the character so well, the challenge of not having Luc Besson as a producer on the film, how her view on violence in the film has been shocking to some audiences, and the compromises that she’s had to make in order to survive in her own life. She also talked about how she’ll next be directing Beyond Good and Evil, written by Nicolas Constantine and about serial killer Richard Ramirez, and what she’s learned from working with and watching such filmmakers as Brian DePalma, Luc Besson and Quentin Tarantino, and even called Tarantino’s next film, Django Unchained, which she’s read, a “magnum opus” that she’s astonished with. Check out what she had to say after the jump:

Question: How did this whole project come about? What sparked the idea for you?

RIE RASMUSSEN: There’s a lot of history to all journeys, or all destinations, I should say. There are a lot of autobiographical issues in this film. Human Zoo was looking back at my life, at 15, leaving a socio-political country like Denmark that is a very correct country. I come from a very well-educated university family, and went to Huntington Beach in Southern California, following a surfer, and I met the bad end of the surfboard/skateboard community. I met these kids who were basically Jackass, for real. Before Jackass was on MTV, this is what it was. This was when Big Brother was a skateboard magazine, and Chris Pontius and Jeff Tremaine were running and writing for the magazine, before the Jackass TV show. There were a really interesting coalition of events that happened in my life, which is very much like Adria in this war zone, and this young girl being raised by this war profiteer who’s a sociopathic lunatic. At the same time, he sounded reasonable, many times. It’s masturbation for writers to be able to write this absolutely outrageous personality, in a character that you somehow agree with, part of the time, at least. In the end, you’re like, “We have to kill this animal because it’s too dangerous.” But, that was part of the story.

Then, another part of the story was that the mother of Linh, who now has a Danish last name that is the same as part of my family, had been sold into prostitution in Moscow when she was four years old and she, herself, since she was a very little girl, had been imprisoned there. Her mom had gotten her out, but the mother did not make it out. So, she made it to Denmark and part of my family was trying to adopt her, which was an atrocious affair because Denmark was really resistant against any sort of humanity. That was so weird to me. If you’re born in America, you’re born in Canada, you’re born in Denmark, or you’re born in Sweden, you were born into a comfortable and rich country with a good social structure, and you won the ovarian lottery. If you’re born in Serbia or you’re born in Vietnam, your mother could be sold into prostitution, and you lost in the ovarian lottery. You’re looking at this stupid invisible line that’s surrounding you, keeping you from being an accomplished, fulfilled individual, or even from being a human being that has a right. That is just so baffling, to me. This invisible line made with the blood of men and their violent agenda actually keeps humanity at such a low. And, there’s no better place to tell a story about lines dividing nationalities and cultures than ex-Yugoslavia and Serbia and Kosovo. Men went over there and bombed because of the ethnic discrimination that was going on in Kosovo, and earlier the ethnic discrimination, purification and cleansing that was happening in Bosnia, which Angelina Jolie made a movie about (called In the Land of Blood and Honey). Good on her, for that. So, this is speaking about the injustices of the human zoo with its ovarian lottery.

Since I’ve traveled so much, my entire life, it’s something I became acutely aware of, and it bothered me. Part of the story was taking myself, who came to New York at 15, and then explored the world and ran into the wrong kind of male animals. In that sense, male animals raised me, after that. I was raised around this very sociopathic character who was extremely charming and very endearing, in many situations, but at the same time, didn’t have the point of views on life that are beneficial for society. The same actor who plays Shawn in Human Zoo, was also in Thinning the Herd. He says, “All things are more beautiful when set on fire,” which is this dialogue of destruction. The actor who plays Shawn has been my creative partner for the last 15 years, and also the inspiration for this character. All of that is very autobiographical, or things I’ve seen happen, like the scene in the bar where Shawn takes off his clothes. In real life, the actor did that. I’ve seen that. That’s a scene where people are like, “That’s really not believable,” but I’m like, “Well, that actually happened.” Obviously, in no uncertain terms, this is a very personal film, even though it’s as aggressive as it is. I’ve been in some crazy situations in life, especially being surrounded by this alpha male, animalistic energy.

When you wrote this, did you always know that you were going to direct it and star in it as well?

RASMUSSEN: I wanted to direct it, for sure. I wasn’t sure about starring in it. I based a lot of the character on my friend’s girlfriend, at the time. She was Croatian, and a lot of the characteristics and the way that I played Adria was very her, when I first met her. But, I wasn’t sure that I was going to act in it. It just became easy because I had just been in Angel-A. Everyone was like, “Oh, my god, that’s so much,” but for me, it was easier than having to deal with an actress who didn’t know her lines or didn’t understand the character. But, say that it’s harder ‘cause I get more props.

What were the biggest challenges in making this film, and what did you find the most rewarding about the experience?

RASMUSSEN: The biggest challenge was that I ended up not having Luc Besson as a producer. Being a first-time filmmaker, I wish I had had him as the producer. That was a really big challenge, and that’s one thing I will never repeat again. I want a really good producer who’s there for me. That’s one thing that I will not make a mistake on again. It was a challenge, and it was also the downfall. The most rewarding part is to speak to the audience at the film festivals. I did a lot of film festivals and a lot of Q&As and a lot of traveling with this film, and there’s nothing better than being with a film festival audience and getting into a discussion with them, even the people who don’t like it. It’s fun. I love that. That’s just awesome. That’s my favorite part of it. You want to convince the people negative about it otherwise. You want to poke holes in their negativity. That’s fun. I love that. It’s like going out at night and flirting with a hot girl or hot boy, and getting that hot boy or hot girl. You’re like, “Right on!” That’s exactly the same thing. It’s really rewarding.

Are you finding that American audiences are able to relate to this film and subject matter?

RASMUSSEN: Yes because it’s bad-ass and entertaining enough that boys are like, “Woah, this is cool dude!” And then, the girls get the sensitive love story and the poor girl who’s trying to raise herself in this male world, and trying to become a woman, and trying to find her sexuality in all of this mess. A lot of females relate to that. And then, the sensitive males catch the whole package. I feel that they do relate to it because it’s entirely influenced by the American filmmakers who brought me up, being a child watching movies. It’s entirely inspired by my experience in America with the American culture. Americans fuck around because they have easy lives. The rest of the world doesn’t fuck around that much because they have really hard lives. Life is hard, in the rest of the world. You’re worrying about surviving, and you’re worrying about class systems, and there’s a social structure that’s very innate, in these traditional communities. In America, and especially California, it’s just balls-to-the-wall.

I grew up in a very responsible, social, Democratic community, and destruction was a bad word. But, in California, destruction is a rad word. The juxtaposition of the two is really what made me into who I am today, in my battles with how fun it is to be bad, and how wrong it is to be bad. My barometer switches. I got in some trouble, in my day, mainly by being around male elements of extremely controversial actions, all the time. I got in a lot of fights. I was on the sidelines of a lot of craziness, which was very interesting.

Did you find that people wanted you to tone down the violence and the sex in this film?

RASMUSSEN: I was nominated in Cannes with Thinning the Herd, my short film in 2004. In 2005, I made Angel-A with Luc Busson, instead of making my own film. And then, I traveled with Angel-A for two years because I was the only one who spoke English. So, me coming in with Human Zoo and wanting to make it, they trusted me. It was such a minimal budget that it didn’t even matter. I’m a first-time feature filmmaker and they were like, “There’s less money, and you get to deal with it.” In the scope of what they were dealing with, no one cared what was going to happen. And then, I was their first Berlin selection, opening in Berlin in 2009. I think it actually happened because I fell through the cracks. I was allowed to meander in my crazy universe.

Are people only shocked by it because you’re a woman?

RASMUSSEN: It’s no more violent or graphic then movies that men make. I’m not ill-informed about movies. I like movies that take it to that next step. We’ve seen the movies that have done this, so this movie is going to do that. It’s not that it’s more violent then any male movie out there because it’s not. It’s more my take on the violence and my way of shooting the violence, and then that I am trying to bring it to that new level. It’s more the innovative view on the violence, then anything. And then, you add in that it’s a woman, and they are just on their ass.

If a man had made this, everybody would be like, “Oh, this a cool way to shoot this. This is fucking violent!” But, I don’t know if a man would have gotten away with it. It’s NC-17. I don’t know if other men would have been able to sell it. Somehow, I look innocent enough that people think it can’t be as bad as it was, on the page. And, it’s not just violent. I like to say that it’s Badlands mixed with Chopper. It goes crazy, and then it’s poetic. It has this human story of Adria, and what’s going on with her, and then this sociopath that can only exist in this war environment. He would be in jail or dead, otherwise. That’s why the war ends, and then he ends. It’s both a human story, and this explosiveness in between.

This film really shows the compromises made in life, in order to survive. Do you feel that you’ve had to make compromises in your own life, either personally or as a filmmaker?

RASMUSSEN: Not at all, as a filmmaker, which is great. I’ve made compromises to survive in life, and to be able to do what I want to do. But, once anything has been put on screen, I’ve never made a compromise. In my personal life, to get to make that sort of art, I’ve made a lot of compromises. I don’t live comfortably. I’ve lived out of a suitcase for the last 15 years. I have lived without a dime to my name, for a very long time. I have eaten canned beans, and I have slept on floors. And, I’ve also lived in obscure environments. We were in Kosovo. I went to Afghanistan. I’ve been in Serbia. I’m always on the road, and there’s a very male-dominated energy where I am. There’s that aggressive energy surrounding me, all the time. So, in personal peace and harmony, I’ve totally made a gazillion compromises. On screen and on film, I haven’t made any compromises. Not yet.

Do you have any idea what you want to do next, as a filmmaker?

RASMUSSEN: I have a script that’s by Nicolas Constantine. It’s called Beyond Good and Evil, and it basically looks into the issue of whether we’re born evil or taught to be evil. Is it societal, or is it genetic? It’s based on Philip Carlo’s book, The Night Stalker, and it’s about Richard Ramirez’s life. You really get to see choices and things that happened in his life, where you really get to pose questions and answer questions about the evil within men and the evil that men do.

Are you looking to continue writing and directing your own films, as well as acting in films that you don’t direct?

RASMUSSEN: I’m directing Beyond Good and Evil. I’ve got three scripts that I’m burning to tell, but Beyond Good and Evil is one of the most well-written scripts I’ve ever gotten, in my lap. The fact that they even want me to direct it has me over the moon. So, I’m doing that next, but after that, I have three scripts that I’m absolutely wanting to do. And, if anybody wants to stick me in a film and they’re dumb enough to do it, then I’ll do it, anytime, anywhere, any place.

Film is my passion. I had no money, after Human Zoo. I was completely broke. It was horrible. My film was in Berlin on opening night, but I couldn’t even get to Berlin. And then, Quentin Tarantino invited me to the set of Inglourious Basterds. After coming from directing, I just went and got him coffee on set, so that I could live with the cast and be at the Berlin Film Festival. If something rad is going on and it has to do with film, I want to be there. If it’s getting coffee, I don’t care. It’s a passion of mine.

What do you feel you’ve learned from working with and watching people like Quentin Tarantino, Luc Besson and Brian DePalma?

RASMUSSEN: At the time, Brian DePalma was such a hard-on for me. I was just really losing my shit, to work with him (on Femme Fatale). I was on set for as much as I could be, which was probably a month, and I only shot for four or five days. But, I did do that one, long steadi-cam shot that is the Brian DePalma signature. That was so awesome for me. It was following me! Who even cares about the rest of the movie? No. In my formative years, Brian DePalma taught me by watching him. From when I was 18 to 25, there was nothing better than Brian DePalma.

From 12 to 15 or 16, there was nothing better than Luc Besson, with Big Blue and La Femme Nikita. That was it. With Angel-A, he wanted to prove to everybody that he could make a feature film in six weeks, put it out five months later, package it and distribute it for no money.

Watching Quentin Tarantino write his new magnum opus, motherfucker of a film, Django Unchained, has been more than a lesson in writing. I always knew that the man was genius, but I have been astonished at what comes out of him. He’ll read me the scenes. He’s like, “I just had to redo this scene and I want to read you this new dialogue I wrote.” He read me this dialogue, and I was just on my ass. Just to watch him rattle it off like that, he’s genius. So, yeah, you learn. I pay attention. My eyes are wide open, and my eyelids are pinned to the back of my head.