Directors come in all shapes and sizes. Some are incredibly hands on with their department heads, giving explicit direction as to what they want specifically in terms of each costume or prop or shot design. Others are more deferential, acknowledging that they hired these department heads for their expertise, and offering only general guidance while allowing them a significant degree of freedom. But the relationship between a director and a cinematographer can at times be the most intimate one on a set, as the cinematographer is quite literally the eye through which the entire story is being told.

Many filmmakers find a cinematographer they work well with and stick with them for the majority of their career (see: Steven Spielberg and Janusz Kaminski), while others like to change things up from film to film. But there are also some directors who decide to serve as their own cinematographers. This doubling of responsibilities can be incredibly taxing, which explains why it doesn’t happen too often, but for his new zombie movie Army of the Dead filmmaker Zack Snyder decided to do just that: become his own cinematographer.

So now seems like as good a time as any to take a closer look at filmmakers who have served as their own directors of photography, and to consider the pros and cons of such a move. Here are 11 notable filmmakers who have shot their own movies.

Steven Soderbergh

The most famous director/cinematographer is certainly Steven Soderbergh, who officially started working as his own DP on 2000’s Traffic under the pseudonym “Peter Andrews” (a name he now uses for all of his films). Soderbergh also frequently serves as his own editor as well, and the decision to shoot his own movies was one of economics – he created a workflow in which he can have a cut of his movie completed the day it wraps, as his DIY approach cuts out the various conversations a director might have with their DP and editor as post-production approaches. Granted, Soderbergh is a unique beast – this workflow would be disastrous in 99% of cases, but there’s truly nobody quite like Steven Soderbergh. Moreover, he’s clearly not phoning it in. He’s got a distinct aesthetic that works tremendously, with a confident and story-focused approach to his shot compositions. He’s not just one of the best directors working today, he’s also firmly one of the best cinematographers as well.

Robert Rodriguez

Another filmmaker noteworthy for his DIY approach to making movies is Robert Rodriguez, who began his career by writing, directing, shooting, editing, and writing the score for his debut feature El Mariachi. In many ways he never looked back, as he’s maintained some combination of those filmmaking jobs on all of his films since, save for a couple of exceptions. He worked with other DPs throughout the 90s, but resumed his own cinematographer duties in 2002 with the advent of digital photography, setting up his own studio in Austin, Texas where he could easily manage various responsibilities throughout production. Having been an early advocate of digital photography, Rodriguez embraced the boundless possibilities of shooting digitally with films as varied as Sin City, The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl 3-D, and Planet Terror. And yet for his biggest budget yet, Alita: Battle Angel, Rodriguez deferred cinematographer duties to the legendary Bill Pope, so he’s clearly not opposed to collaborating at this stage in his career.

Quentin Tarantino

One could probably safely assume that Quentin Tarantino’s friendship with Robert Rodriguez inspired him to pick up the camera for his 2007 film Death Proof (which was released alongside Rodriguez’s Planet Terror as part of the experimental Grindhouse release). To date, Death Proof is the only time Tarantino has served as his own cinematographer, but it remains an exciting outlier in his filmography. There’s a handmade quality to Death Proof that serves Tarantino’s intimate approach well, as the whole idea of the film was to make something that would feel like a grindhouse movie. As with much of Tarantino’s filmography, Death Proof feels like a “see, I can do this too” one-off of sorts – in more ways than one.

Reed Morano

There’s a not insignificant number of cinematographers who later made the jump to directing, but very few of those stayed on DP duties when helming their own movies. Reed Morano is one of those few, as the cinematographer behind films like The Skeleton Twins and Kill Your Darlings as well as episodes of Looking and Vinyl also shot her 2015 directorial debut Meadowland. Morano continued to serve as her own DP on 2018’s post-apocalyptic drama I Think We’re Alone Now, maintaining her striking naturalistic aesthetic throughout. And while the filmmaker has also hired DPs on films like The Rhythm Section, she’s more than proven capable of juggling both responsibilities and likely will again.

Alfonso Cuarón

Alfonso Cuarón did not originally intend to be his own cinematographer on his intensely autobiographical 2018 film Roma, and that “accident” ended up earning him an Oscar for Best Cinematography. Cuarón’s longtime collaborator Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki – the only DP to win three Best Cinematography Oscars in a row – was initially set to shoot Roma, but scheduling conflicts forced him to drop out at the last minute. Having gone through prep with Lubezki, Cuarón decided to tackle the film’s unique aesthetic himself. Presented in black-and-white but shot in pristine 6K with a locked down, controlled approach, the effect of this technique is as if you’re stepping into a memory. That was the point of Roma of course, as the film is an intensely accurate recreation of events from Cuarón’s childhood, and in hindsight it feels like no one but Cuarón could have shot this movie. A happy accident indeed.

Paul Thomas Anderson

So this entry is a bit controversial, as Paul Thomas Anderson maintains he was not the cinematographer on his 2017 film Phantom Thread. Indeed, the movie has no credited cinematographer, as PTA and his camera team took a collaborative approach to crafting the film’s visual aesthetic. The decision came after PTA’s frequent collaborator Robert Elswit had a scheduling conflict (and the two had butted heads on Inherent Vice), and speaking with EW at the time of Phantom Thread’s release Anderson explained how he views the film’s cinematography:

“That would be disingenuous and just plain wrong to say that I was the director of photography on the film. The situation was that I work with a group of guys on the last few films and smaller side projects. Basically, in England, we were able to sort of work without an official director of photography. The people I would normally work with were unavailable, and it just became a situation where we collaborated — really in the best sense of the word — as a team. I know how to point the camera in a good direction, and I know a few things. But I’m not a director of photography.”

PTA went on to say that if one could give credit on Phantom Thread, it would be his longtime gaffer Michael Bauman, but I think PTA qualifies for this list given that he was still leading the camera team on the film. And let’s be honest, this movie looks like a PTA movie. Clearly the guy knew what he was doing.

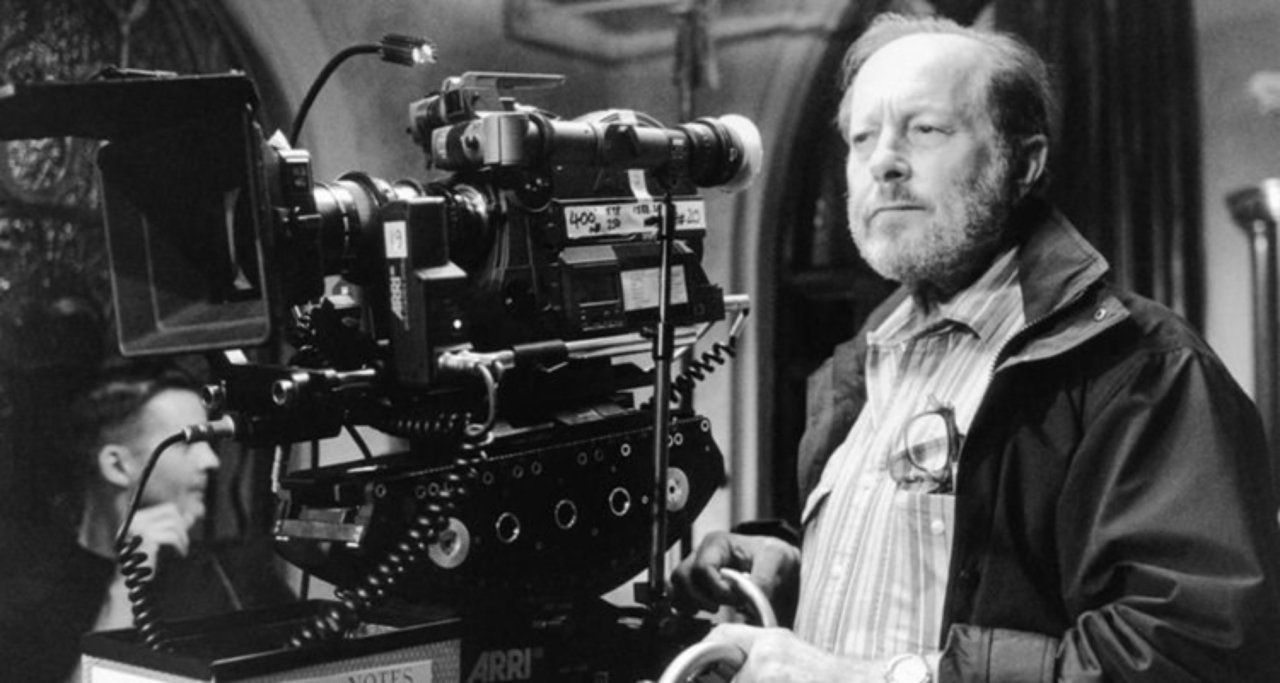

Nicolas Roeg

Filmmaker Nicolas Roeg got his start as a cinematographer before becoming known as the director of films like Don’t Look Now and The Man Who Fell to Earth. In fact, Roeg served as the second unit cinematographer on Lawrence of Arabia before being hired as the DP on Doctor Zhivago, so it’s no surprise that when he started directing his own films, he served as his own cinematographer. While it only lasted for his first two directorial features – Performance and Walkabout – Roeg’s experience behind the camera no doubt influenced his filmmaking approach as his career blossomed.

Cary Joji Fukunaga

Before Cary Joji Fukunaga made the jump to feature films, he directed a lot of short films that he shot himself. And even after his first two movies – Sin Nombre and Jane Eyre – were under his belt, he was collaborating closely with cinematographer Adam Arkapaw to craft a striking cinematic aesthetic for the first season of HBO’s True Detective. Indeed, one of the most memorable moments from that season was a stunning oner in which Matthew McConaughey busts a house, so it’s no surprise then that for Fukunaga’s next feature, he assumed cinematographer duties himself and did a fine job. That feature was one of the first-ever Netflix original films, Beasts of No Nation, and while Fukunaga hasn’t shot anything himself since then, it remains a striking film that serves as a reminder of Fukunaga’s versatile talent.

Doug Liman

Having directed The Bourne Identity, we can reasonably credit filmmaker Doug Liman for the “shaky cam” aesthetic that became prevalent in action films throughout the 2000s. And while he didn’t officially shoot The Bourne Identity himself, Liman has been known to operate the camera on his own movies, and officially served as his own cinematographer on two key early films from his career: Swingers and Go. Liman wouldn’t officially DP his own film again until 2010’s Fair Game, but he’s a filmmaker known for changing things on the fly and bringing a visceral quality to his aesthetic approach – even when he’s not the cinematographer, he’s a boots-on-the-ground kind of director who’s intimately helping shape what ends up onscreen.

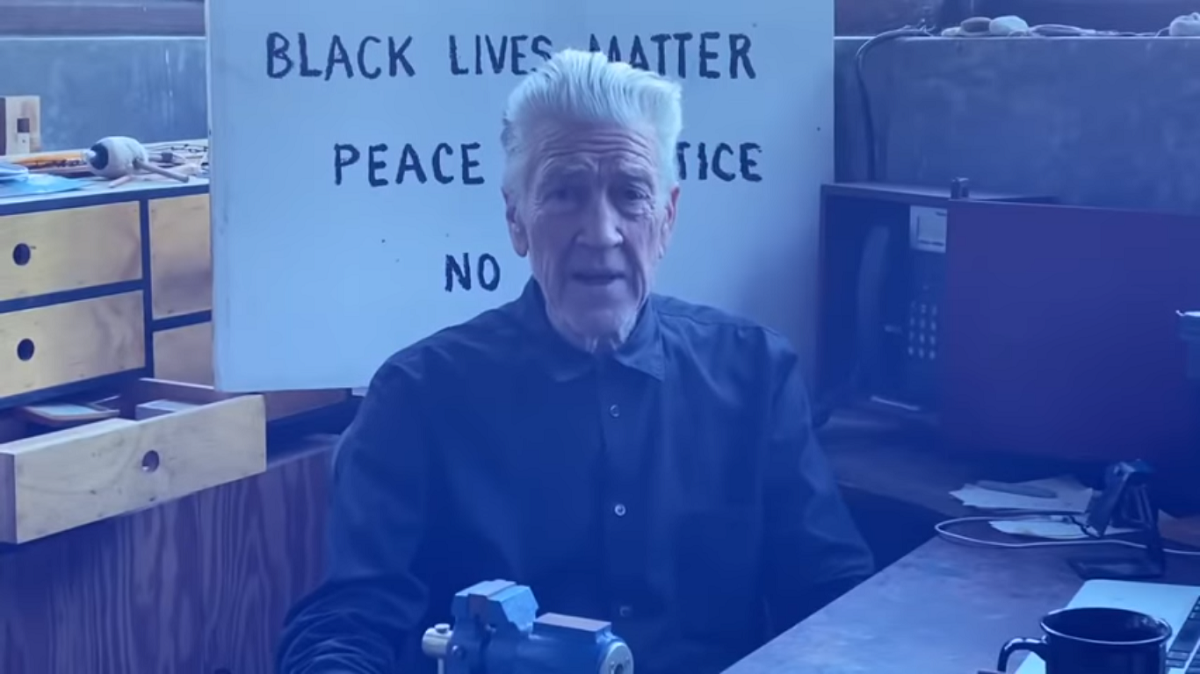

David Lynch

One would be forgiven for thinking David Lynch has shot most of his own stuff, given how quintessentially “David Lynch” each of his projects feels. But to date he has only officially served as his own cinematographer on one film, 2006’s Inland Empire. The decision to shoot (as well as edit) the movie himself came about as part of the switch to digital filmmaking in the early 2000s, and the result is somewhat experimental. This wasn’t Lynch’s first rodeo as he’s been DP’ing his own short films since 1969, and handled cinematographer duties as recently as 2018’s short Ant Head.

Zack Snyder

And this of course brings us back around to Zack Snyder, whose feature debut as a cinematographer was long overdue. The Dawn of the Dead filmmaker first burst onto the scene thanks to his striking commercial work, but as early as his first film it was clear that Snyder was a tremendously gifted visual stylist. For his second feature, 300, the ambitious aesthetic was all Snyder’s idea (gorgeously composed by cinematographer Larry Fong), and the director has made great use of very specific storyboards and shot compositions throughout his entire career. His first credit as a cinematographer came on the 2017 short film Snow Steam Iron, and for his Netflix zombie feature Army of the Dead, it’s no surprise that Snyder beautifully captures the film’s visuals as his own cinematographer.