It was shortly after the promotional campaign for Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame had concluded. Directors Kirk Wise and Gary Trousdale and writer Tab Murphy had been summoned by producer Don Hahn to a crummy Mexican restaurant in downtown Burbank that is, mercifully, no longer there. “Don made it clear to me and Gary that if we wanted to work on another project and work with the same team, we had to come up with a project right away,” Wise remembered. Trousdale echoed the sentiment: “It was Don Hahn who pulled us together and said, ‘You’ve done a couple of movies, the studio is happy with you now, this is your chance – if we want to do another movie together, keep the crew together, and do something that we want to do, we’ll have to sit down and think of it or the studio is going to tell us what to do.’”

Over nachos, salsa and “god knows how many pitchers of margaritas” (according to Trousdale), they threw around ideas for what they wanted to do next. They were fatigued, not just from making a movie as huge and complex as The Hunchback of Notre Dame, but of the formula that had settled into what was then known as Walt Disney Feature Animation. They wanted to steer away from the big, Broadway-style musicals that the studio had been making, more or less uninterrupted, since the so-called Disney Renaissance began in the late 1980s, to something that Walt Disney himself would have made in live-action in the 1950s or 1960s – movies like 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea or The Island at the Top of the World. This new animated feature would be a big, boisterous action movie. They even came up with an ingenious way to describe (and ultimately sell) the project. As Wise said, “We wanted to make an Adventureland movie instead of a Fantasyland movie.”

It was a quietly revolutionary idea that would fuel the project that would eventually become Atlantis: The Lost Empire, a movie that looks and feels unlike anything else in the history of Walt Disney Animation Studios (as it’s known today) and, had it been as successful as everyone thought it was going to be, would have changed Disney forever.

Over the nachos and margaritas, they talked about concepts they wanted to explore. “We started spit-balling what subject could we built this around. We decided it should be a period film. We loved the combination of late Victorian or early 20th century technology being applied in a futuristic fashion. And that’s something that all of those stories had in common. We also talked about team movies,” Wise said. “We thought, 'What if we cross-pollinated the idea of an adventure/quest movie set in the early 20th century/late 19th century with a ‘guys on a mission movie?'" Initially they considered a straightforward adaptation of Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth, until they actually read it. “It’s a great concept but it just doesn’t go anywhere,” Trousdale said of Verne’s original story. “They don’t get to the center of the earth, they run away, and a third of the book is in total darkness.” Still, the idea of tunneling to some mystical subterranean destination appealed to the team. Quickly, the idea of exploring the idea of Atlantis bubbled to the surface.

Unbeknownst to the team, Joss Whedon, then best known as the creator of the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer, had developed an Atlantis project a couple of years earlier during his brief, uneventful stint at Disney Animation. Whedon, who wanted to work on the type of elaborate animated musicals the Atlantis team was shying away from and completed a draft (with songs!) for a Marco Polo musical, described the Atlantis project as “Journey to the Center of the Earth meets The Man Who Would Be King.” The final film doesn’t contain any of these elements and the eventual Atlantis: The Lost Empire team never read his draft, but Whedon received credit anyway. “We weren’t aware of [that script’s] existence until Joss Whedon showed up in the end credits as a writer and we went, ‘The fuck is this?’” Trousdale recalled, matter-of-factly. “Then we found out, oh he wrote something with Atlantis in the title and the attorneys thought it would be easier to just cave in and give him credit instead of fighting his agent.”

Getting the greenlight for the project came surprisingly easy. “It was an odd time,” Hahn said. Disney chairman and CEO Michael Eisner, who was a big supporter of Wise and Trousdale, was bitterly feuding with Roy Disney, Walt’s nephew and a powerful member of the board, for control of the company. And executive Peter Schneider, the president of Walt Disney Feature Animation, and Thomas Schumacher, Disney Studios present, were focusing more of their attention on Disney Theatrical. Hahn continued: “I don’t feel like we were under a microscope at all. Because of the distractions at the time, the political distractions at the highest level, I think people were like, ‘This could be a cool idea. Let’s try it.’ We weren’t under scrutiny for the story aside from just trying to make it work.” It was not unlike the situation with animation in the early 1960s, when Walt was busy with live-action and Disneyland and creating a futuristic city in Central Florida. “There was definitely a different vibe at the studio. It didn’t feel like Eisner was gone all the time. He was just distracted,” Trousdale said. “There was the whole machinations with Roy and the board and a power struggle. So he didn’t have as much time. We had Peter and Tom, who were watching over us a lot more, and they were his eyes and ears – which they always were. But he didn’t show up as often. And Roy, of course, was not as present.” Wise pointed out that Eisner was the executive at Paramount who gave the greenlight to Raiders of the Lost Ark and teamed with George Lucas for the Indiana Jones Adventure at Disneyland. “I think he had a real appreciation for the genre and got how it would be a good fit for Disneyland, because of his involvement in those movies and those attractions,” Wise said. As for that scrutiny and oversight, avoided initially, it would eventually be felt by the entire Atlantis: The Lost Empire team.

As production got underway, they added a key member of the team: John Sanford, who served as the artistic supervisor for story. He was finishing work on Mulan at Disney’s Orlando satellite studio. Uninspired by the projects that he knew were in the pipeline, he called Trousdale and asked what he was working on. When Trousdale explained the project, Sanford knew he had to be a part of it. “It was unlike anything I’d ever heard of,” Sanford said.

And as much as they knew that they wanted Atlantis: The Lost Empire to feel different, the creative team wanted it to look different too. As Hahn said, the project “was trying to do something more comic book,” and Wise and Trousdale found chief inspiration in the work of comic book creator Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy. Emboldened by the experience the Hercules team had with legendary illustrator Gerald Scarfe, team Atlantis brought Mignola in to provide character designs, work on design elements like the Atlantean temples, and work on story beats. “When Mike was brought into the process, we had already started breaking down and analyzing his style and incorporating motifs and elements of it into the background of the characters,” Wise said. “And it was really gratifying that he jumped on it with such enthusiasm. He got along great with us and our whole team. He contributed tons of sketches and ideas.” One day, Mignola drew left a drawing on Wise’s desk. It was a “blind, stone flying fish with lighting shooting out of its mouth.” Under the sketch, Mignola left a note. “I have a really cool idea! Call me!” Mignola wrote. “That’s pretty much how the climax of the movie evolved,” Wise said. They further differentiated the look of the film by presenting it in the CinemaScope widescreen format. Initially executives worried about the size of the paper that would be needed, since the format contributed to the expense of costly Disney flops Sleeping Beauty and The Black Cauldron. The animators who worked on Sleeping Beauty were drawing on paper the size of bedsheets and there was talk of moving the entire Atlantis team to a different building, equipped with specialized desks. But a compromised was reach: the characters and backgrounds would actually be smaller, which worked due to their highly stylized nature.

Everything about Atlantis was huge, beginning with Murphy’s script, which concerned an eccentric benefactor named Mr. Whitmore (John Mahoney) who tasks a team led by nerdy cartographer Milo Thatch (Michael J. Fox) and a band of morally nebulous mercenaries headed by Lt. Rourke (James Garner) to find the lost city of Atlantis, populated by technologically advanced natives, including the beautiful Kida (Cree Summer).

“It was the biggest animation script I’d ever seen,” Sanford said. “It was massive.” Wise remembers screening the first two acts of the movie, in storyboard form, and it running over two hours. “Everybody had to sit back – our bosses and us and our team – and we all said, ‘We have got way too much stuff in this movie,’” Wise said. “The animation studio at that time was a machine that was specifically designed to crank out 90-minute movies. And that’s on the generous side. It was designed to crank out 85-minute movies. So the notion of doing anything that went beyond that running time, the machine was just not designed to produce and that boiled down to number of artists, manhours involved and release schedules.” A number of characters, including a phony mystic that went on the journey, “Mr. Whitmore’s stupid nephew” (according to Trousdale) and Milo’s pet rat Plato, were deleted (in part because it felt too similar to the cute animal sidekick trope of the other Disney animated films). And the number of action sequences and monster attacks were dramatically pared down. Mignola, who we must remember created Hellboy, called the movie a “monster parade.” “If you run into a monster, that’s great. If you run into five monsters, not as great,” Hahn said. “The journey to Atlantis became less important than getting to Atlantis.”

The filmmakers’ attention turned from throwing monsters at the explorers to giving the Atlanteans more dimensionality. “We wanted to make them characters and interesting and give conflict to the crew that they really did think they were going to waltz in, loot the place and waltz out,” Trousdale said. Wise continued: “Ultimately, we decided to sacrifice several big action set pieces and keep sequences where Milo bonds with the explorers, where he learns more about their backgrounds, where we show the developing relationships between him and the team.” It was instrumental in Hahn’s sense of storytelling. “The lesson I learned is that people don’t really care about a place, they care about the people,” Hahn said.

But there were also elements that dictated the deletion of key set pieces – their budget was dramatically diminished. “Our budget got slashed at one point and we had to make more tough choices on sequences where we got rid of all the shadows so the animators wouldn’t have to animate them,” Wise said. The team had started out making a movie of a certain scale when the movie began, and wound up with a much different movie. “When they initially started to make the movie they were given a certain budget so they were planning for a certain level of complexity in animation,” Sanford said. “They saw this big movie and I know they called the guys in at one point and said, ‘I know we said this is what you could do but now we’re saying you’re going to have to do it with this.’ I remember Kirk telling me that story a few years later. He said, ‘All they kept saying was that they were really sorry.’” The executives might have been sorry, but the cuts remained.

Along with the action sequences, Atlantis, imagined as a harder, rougher action adventure, continued to lose its edge. During production the Columbine shooting happened. Executives scrutinized on what they referred to as the “level of activity,” corporate-speak for gunplay. “It was decided during production that we should scale that back. We didn’t want to give everybody a gun and have them shooting all the time. Let’s just not go that direction,” Trousdale said. After Columbine, crew members wondered if the movie was too intense. The adventure remained but the man-eating monsters and muscular shootouts became a causality of the process. (Watching the movie now, the most striking thing is that one of the characters smokes cigarettes throughout the entire movie.) “The hard edges got rounded off little by little, just because the company was used to making a certain type of film. And there were certain aspects of storytelling that made people at the time really nervous,” Sanford said. There were certain realities, too, that the production needed to face. “We were aware it had to be a Disney movie, PG or less,” said Hahn, acknowledging that the throughout the process “the edges do get knocked off.”

Another late-in-the-game production hiccup occurred when the team realized that the movie’s gorgeously animated prologue, showing a group of Vikings looking for Atlantis and using the same ancient manuscript that would guide Milo and his team, wasn’t working. “The Viking prologue set up a movie about finding a book and two sequences later, it’s not about finding a book, it’s about finding Atlantis,” Sanford said. He devised a new sequence, which would showcase the destruction of Atlantis – how it “used to be above the water and now it’s below the water” – and introduce us to a young Kida, who witnessed the cataclysm. Sanford calculated that the Viking prologue had cost $5 million to produce (it was fully animated and color-timed) but sheepishly pitched the new idea to Hahn. Hahn agreed and told Wise and Trousdale, who immediately took to the idea. Trousdale storyboarded the sequence overnight and pitched it to executives the next day. They got the go ahead.

Elsewhere in the company, there were big plans afoot for Atlantis: The Lost Empire. “There was a lot of interest from elsewhere in the company because it was so different,” Hahn said. At Disneyland, there was an ambitious plan to redo the Submarine Voyage, an attraction originally themed to one of the Atlantis touchstones: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. A poster hung in the park for what was known as the Atlantean Encounter, warning guests, “Don’t waste your air screaming.” (The most elaborate version of the attraction featured a full-sized volcano that the Disneyland Monorail would pass through.) “Gary, Don and I had the pleasure of going to Disneyland after hours to the submarine attraction, covered up by barricades and scaffolding and going into one of the submarines and looking at a demo of what was to be, at the time, a planned retrofit of the submarine ride,” Wise said. “The voyage was going to be narrated by Preston Whitmore. There would have been an encounter with the Leviathan. Other characters were going to make appearances by squawking in on the intercom. It was going to be much more focused around mystery and adventure and excitement, rather than a casual tour of underground ruins.” Sanford was brought in to consult on the script, since multiple characters would be talking over the submarine’s communication system. “They were going to retool the sub to make it look like the [expedition’s submarine] Ulysses,” Trousdale said. “It was very cool, I have to say,” Hahn admitted. “It was sad to see that go.”

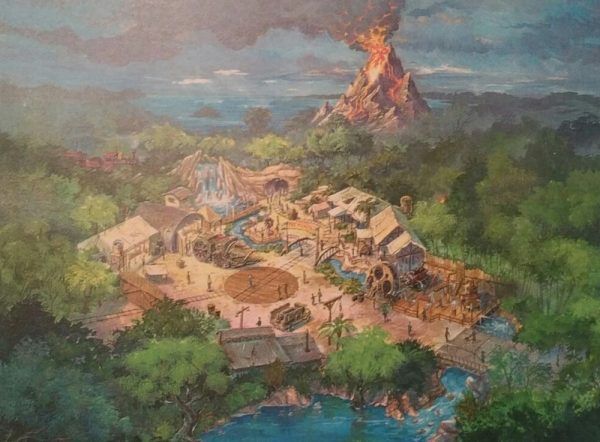

Another project on the docket at Imagineering was Fire Mountain, a rollercoaster and new entry in the legendary chain of Disney “mountains” (Space Mountain, Splash Mountain, Big Thunder Mountain Railroad, and Expedition Everest: Forbidden Mountain). This attraction would be located in Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom in a section of the park that had inspired the entire Atlantis: The Lost Empire endeavor – Adventureland. The Fire Mountain Intent Scope Document, produced for Imagineering, describes the plot of the attraction: “To prove the world that Atlantis is real, Whitmore Industries has created an amazing transportation system that not only retraces the original route of discovery but enlists the experienced help and expertise of some of the surviving members of the first Expedition.” “They had a whole ride system that they had acquired that was basically a rollercoaster that you would hang from like you were on a hang glider. You’d hang from your back with your stomach facing the earth and the track above your head,” Wise explained. “In a sense it would duplicate the sensation and the design of the gliders that are used in the final battle of the movie. That was going to take you through the exploding volcano and various other scenarios but it was going to be a flat out rollercoaster thrill ride incorporating this new ride system.” Hahn described the Fire Mountain project as “great.”

And there were plans to expand the world of Atlantis: The Lost Empire for the small screen, as well. It was intended to be a “dramatic half hour” series, and Disney Television Animation’s answer to The X-Files, with Milo and the Ulysses survivors investigating otherworldly phenomena and ancient cultures every week. (There were also plans to, at some point, do a crossover with Disney’s popular animated series Gargoyles.) While Trousdale and Wise were not involved with the television project, they understood that the show was hugely ambitious. “They were going all over the world and checking out all the different things that were offshoots of Atlantis,” Trousdale said. “They played with the idea that we’d planted, which was that Atlantis was the cradle of all civilizations and everything spun off from there and they were going to all of these different places.”

But like the proposed attractions for Disneyland and Walt Disney World, the animated series was quietly canceled. The first three episodes of the television series were cobbled together and packaged as a direct-to-video sequel called Atlantis: Milo’s Return, released almost two years after the original film (you know, when interest had really peaked). The Submarine Voyage at Disneyland was re-themed, only the attraction that opened was connected to Pixar’s blockbuster Finding Nemo. And the Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World is still damnably mountain-free.

And the reason was simple – Atlantis: The Lost Empire simply didn’t perform. “We could kind of seeing coming, a little bit,” Trousdale said. He cited the stiff competition in the form of Tomb Raider, a live-action video game adaptation that was attempting to hit the same action/adventure sweet spot, and a soft minority that claimed Atlantis, with its explosions in place of musical numbers and lack of animal sidekicks, was the anthesis of what a Disney animated movie should be. Wise knew that all of those grand plans (which included an honest-to-god theatrical sequel) were over almost immediately. “Opening weekend. Everybody had the best intentions, the studio really supported the movie, I think they marketed it very well but even the best intentions can’t make up for the fact that if you release the movie and people don’t go,” Wise said. “All the spin-offs and rides and comics and things that were planned for the movie, those get wiped off the table in one stroke.” Hahn said that the company “backed off,” and bemoaned the fact that they didn’t have faith. “In Walt Disney’s day, he would build Sleeping Beauty Castle in the middle of Disneyland four years before the movie came out. It was the promise that that would be part of the experience. That wasn’t the case anymore,” Hahn explained.

Atlantis, the filmmakers had hoped, would open up an alternate stream of Disney animation. Had it been a success, there could have been just as many Adventureland movies made as Fantasyland movies. “That was the hope. That was what we thought might happen,” Trousdale said. “Disneyland has a whole land dedicated to this kind of thing, why not go there?” Sanford agreed. “We would have made more movies inspired by Adventureland. I think that was the moment. There’s an alternate reality somewhere where Atlantis hit with the public,” Sanford said. “And Disney is making a different type of movie. They’re always going to make musicals but I think there’s another kind of movie they could have been involved with.”

Aladdin directors Ron Clements and John Musker were hard at work on Treasure Planet, a fantastical, space-age reinvention of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic novel that the directing team had been trying to make since before The Little Mermaid. Treasure Planet shared a certain sensibility with Atlantis: The Lost Empire, considering the 1950 Treasure Island movie was Walt Disney’s first completely live-action feature. (It also shares a vaguely steampunk-ish aesthetic that mixes classical and cutting-edge technology.) The team behind Treasure Planet, led by Clements and Musker, watched the fate of Atlantis anxiously. “I imagine that [the performance of Atlantis] probably worried them,” Wise conceded.

If Atlantis: The Lost Empire had been a smash, it would have potentially transformed Disney, pushing forward the boundaries of television animation and Imagineering and pushing the company’s beloved animated output in a bold new direction, potentially extending the longevity of 2D hand-drawn animation at the studio. Alas, it wasn’t meant to be. Or maybe Atlantis just sunk below the surface of the earth, still alive, still active … Because the damnedest thing happened – in the years since Atlantis: The Lost Empire was released, it’s become a genuine cult classic.

“It blows my mind. I am hugely gratified that fans of the movie who love it when they were kids, grew up into adults who still love the movie and have shared it with their kids and have created a whole new generation of fans for it,” Wise said. Trousdale said he didn’t realize there was a cult appreciation of the movie until relatively recently. “I didn’t realize it until a few years ago,” Trousdale said. (He, like Hahn, Wise and Murphy, regularly post to a Facebook group dedicated to the movie.) Hahn had an amazing experience at the D23 Expo, the all-Disney convention held every two years. “I came across a bunch of cosplay people who were the entire crew of the Ulysses. They were spectacular,” Hahn remembered. “I walked up to them and said, ‘Hi, you don’t know me but I produced this film.’ The girl who was playing Kita started crying and said, ‘You really made our childhood with this film, can we have a picture with you?’ So I just thought, really?!? It was this emotional thing with these kids of a certain age.” For Sanford, he was working on a DreamWorks Animation project when he noticed that one of his story artists was watching the movie at his desk. The artist told Sanford that it was the movie that made him want to become an animator. A production assistant pointed him toward the conversation about the movie on Twitter and Tumblr. “She pointed out this amazing fandom that has grown up around the movie,” Sanford said.

As for where Atlantis: The Lost Empire fits into the legacy of Disney Animation, Wise has an idea. “We fit into this lull period, this brief experimental period between what people call the Disney Renaissance and what is popularly referred to as the Disney Revival, where the studio was experimenting a little bit with genres and styles in the 2D animation world,” Wise said. “I feel grateful that they gave us so much rope and we were able to go against audience expectations in terms of what a Disney movie looked, sounded and felt like. But at the same time I don’t think we were reinventing the wheel.” And it’s true. While there might have been concessions made and corners cut, there is nothing that looks or feels like Atlantis: The Lost Empire in the history of Disney Animation. The filmmakers took the lack of oversight from Disney executives and used it to their full advantage. In Trousdale’s words, they wanted to “try something a little more beefy, a little more adventurous.” And you know what? They did.