The history of the Walt Disney Company is littered with tantalizing, troublesome what-ifs – rides, shows, attractions, and theme parks that were designed and planned but never built. Disney’s America, a proposed historical theme park nestled in the rolling hills outside of Washington, D.C., was one of those projects. It was unlike anything the company ever mounted, both in terms of its elaborate, educational theming and the firestorm of controversy that the very idea of the project was met with. The bloody battle for Disney’s America is one of the most fascinating, contentious chapters in the company’s history. And one that would leave its mark permanently.

In January 1990, Michael Eisner, Disney’s plucky, recently installed CEO and Chairman, formally announced The Disney Decade, an ambitious, 10-year project that would aggressively expand the Disney theme parks at home and abroad. "This is the '90s - the decade we re-invent Disneyland," Eisner enthused. (One of the keystones of the Disney Decade was a second gate to Disneyland, to be built either in Anaheim or Long Beach, as well as modernizing Disneyland proper.) But by the summer of 1991, the plan for the Disney Decade was already in jeopardy. Costs for the Euro Disney project (later renamed Disneyland Paris) were skyrocketing and a number of projects for the stateside park were being canceled or dramatically scaled back. Expansion was still necessary, but the idea was introduced for smaller, lower-cost parks that were cheaper to build and quicker to open.

That same summer (1991) Dick Nunis, one of the original employees of Disneyland who had eventually risen to president of the Outdoor Recreation Division (he was also a powerful board member who initially opposed Eisner joining the company), convinced Eisner and Disney President Frank Wells to accompany him on a trip to Colonial Williamsburg, the themed historical town in Tidewater, Virginia that had proven incredibly popular with tourists. Eisner, who had recently okayed development on an animated Pocahontas feature, was intrigued. But the strategic planning group, a shadowy, powerful cabal within Disney that had given the green-light to a Disney Cruise Line but dismissed other, just-as-outlandish ideas (like a Disney airline and a network of Disney daycare centers), said that the Williamsburg area wasn’t feasible. It was too out of the way and its business was seasonal.

Still, the idea of a historical theme park was an alluring one. And Eisner and Wells tasked Peter Rummell and the Disney Development team to scout for alternate locations in the area. Almost immediately they identified on a spot – the greater Washington, D.C. area. “It’s no contest,” Rummell told Eisner (who recounted it later in his memoir, Work in Progress). “It has a huge tourist population and they’re just the kind of people who would be interested in a historical theme park.” 19 million people visited the nation’s capital each year. It was a slam dunk.

In secret, Disney began buying up land just outside of the town of Haymarket, Virginia, in Prince William County including securing 2,000 acres formerly owned by Exxon, which the oil company had earmarked for a mixed-use development project but abandoned during the real estate bust of the early 1990s. Utilizing a tactic that Walt employed while purchasing the land for what would eventually become Walt Disney World in Florida, none of the sellers knew that Disney was buying – not Exxon, or the owners of dozens of smaller parcels of land that Rummell and his team were ravenously scooping up. This would continue through the fall of 1992. By the end of their buying spree they had close to 10,000 acres.

In January 1993, Eisner would hold a powwow at Walt Disney Imagineering, the secretive division of the company responsible for developing theme parks and attractions. The group at Imagineering, sworn to secrecy, was led by Bob Weis, a longtime Imagineer who had successfully overseen the Disney-MGM Studios project in Florida just a few years earlier. (Disney-MGM was a project that Eisner had instigated and championed.) “Whatever we ultimately do, it should be built around a small number of emotionally stirring, heart-wrenching stories based on important themes in American history,” Eisner told the group. At the conference many ideas were launched, with lands centered around the creation of the Constitution, another around the Native American experience and stories centered around slavery and the painful creation of the United States were spit-balled.

By the spring of 1993, the land around Haymarket was fully secured and in August, Eisner and his wife toured the site. The trip from Dulles International Airport to the land outside Haymarket took less than 30 minutes and the land was off Interstate 66, a frequently utilized thoroughfare. Eisner was convinced that Rummell (and the watchful corporate planning group) was right – this was the ideal location for the historical Disney park.

But by the fall of 1993, word had started to leak that the land now belonged to Disney. The company thought that they could announce it on their own timetable but that wasn’t the case. It would prove an early, catastrophic setback. “Our focus on secrecy in land acquisition had prevented us from even briefing, much less lobbying, the leading politicians in the state about our plans as they evolved,” Eisner wrote in his memoir. “The consequence was that we lost the opportunity to develop crucial allies and nurture goodwill. The secrecy also precluded seeking out prominent historians, whose ideas and criticisms would have helped us shape our plans, alerted us to potential controversy, and given the project more legitimacy from the start.”

When Eisner called newly elected Virginia governor George F. Allen in early November, the CEO was shocked to learn that Allen was actually in Walt Disney World. Allen called Eisner back from the Magic Kingdom and endorsed the project. (According to Eisner, Allen said: “It’s just the kind of project I want to bring to Virginia.”) Eisner also secured support from the outgoing governor, Douglas Wilder. Both men agreed to appear at the showy public announcement, slated to take place on November 11th.

On November 8th, though, The Wall Street Journal ran a vague story about how Disney was planning to announce a park in Virginia. It sent Disney brass scrambling to connect with local politicians and fill them in on the plans. On Wednesday, a day before the proposed announcement, the Washington Post ran a story with significantly more details. This initial coverage would set the tone for what would come from the paper for the next year – it was adversarial and dismissive. But it also laid out the opposition that would form around the project, almost from day one – the close proximity of the tract of land to the Manassas National Battlefield Park, site of two major Civil War battles; the possibility of local landowners (many of them wealthy and powerful) opposing a theme park so close to their hidden retreats; and fears of clogged roadways and increased pollution from the woefully underprepared Interstate 66.

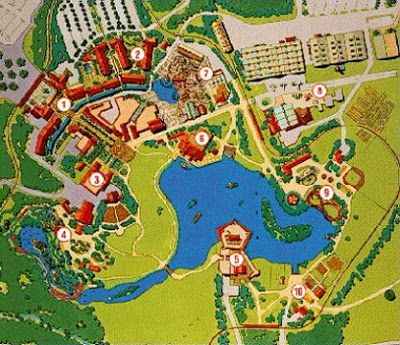

Disney’s America was formally announced on November 12, 1993, with a splashy press conference held in Manassas, near the site of the eventual park. As part of the announcement, Weis presented artists renderings and a scale model of the park. Weis and Eisner outlined the park’s distinct “territories” (Disney’s America’s version of “lands”) which I will now detail here (based on a brochure that was passed out to local Virginia residents to get them excited about the project):

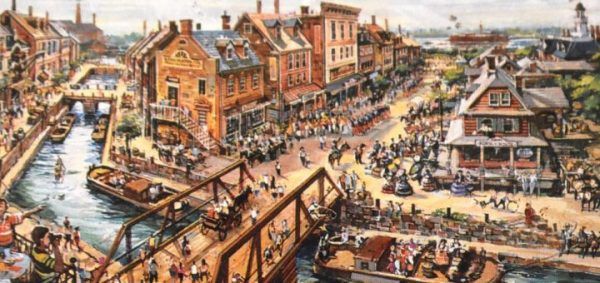

Crossroads USA (1800 – 1850): “A spirited portrait of mid-19th century commerce,” this was the equivalent of Disney’s America’s Main Street USA, flanked by shops and dining. “An 1840 train trestle bride marks the entrance to this territory and supports two antique steam trains that visitors may board for a trip around the park’s nine territories.” This was also the site of a hotel inside the park. “Visitors to Crossroads USA may live the American dream of the Civil War era – literally – by lodging amid the hustle and bustle in a themed 19th-century inn, with additional suites spread throughout the town.” Yes please.

Presidents Square (1750 – 1800): “From the struggle of the colonists and the War of Independence to the formation of the United States and its government, Presidents’ Square celebrates the birth of democracy and the patriots who fought to preserve it.” This area of the park would see the Hall of Presidents, “a moving account of the making of our nation,” relocated from Walt Disney World to rural Virginia, and be home to an outdoor amphitheater for live performances and demonstrations.

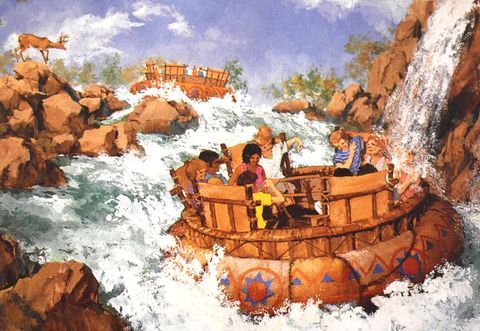

Native America (1600 – 1810): “Native America explores the life of America’s first inhabitants, their accord with the environment and the timeless works of art they created long before European colonization,” the pamphlet reads. Whew boy this one was going to be tricky. “Guests may visit an Indian village representing such Eastern tribes as the Powhatans or join in a harrowing Lewis and Clark raft expedition through pounding rapids and churning whirlpools.” The Lewis and Clark river raft expedition did sound fun and this area was tentatively earmarked for a potential Pocahontas overlay, should the Disney animated feature prove as big a hit as the studio was expecting.

Civil War Fort (1850 – 1870): “Emblematic of our nation’s greatest crisis, the Civil War Fort allows guests to experience the reality of a soldier’s daily life. Inside, the wizardry of Disney’s CircleVision-360 technology will transport visitors into the center of Civil War combat; outside, they may encounter an authentic reenactment of a period battle or gather along Freedom Bay for a thrilling nighttime spectacular based on the historic confrontation between the Monitor and the Merrimac.” Being completely surrounded for a movie about a Civil War battle would have been pretty intense, as would that violent “nighttime spectacular.” The bombs bursting in air indeed.

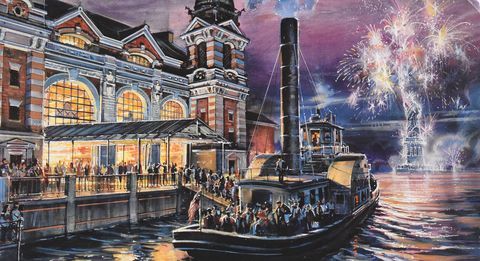

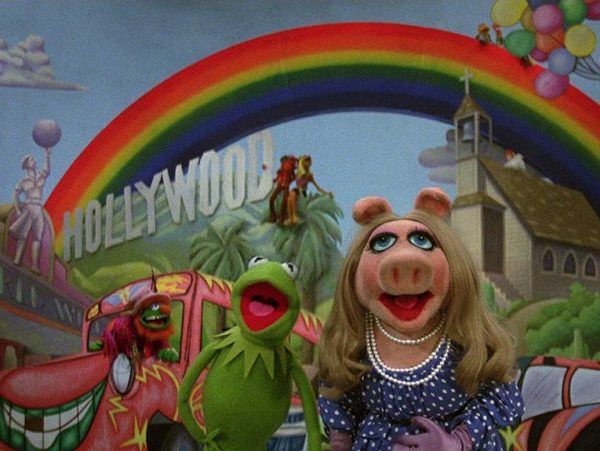

We the People (1870 – 1930): “Framed by a building resembling Ellis Island, We the People recognizes the courage and triumph of our immigrant heritage – from the earliest native settlers to the latest political refugees.” You can tell the Imagineers weren’t exactly sure what was going to go in this section of the park: “A powerful multimedia attraction, We the People explores and explains how the conflicts among these varied cultures continue to help shape this nation.” As Disney’s America was refined, this area of the park was to be home to an attraction featuring the Muppets, who would explain the immigrant experience in a warm and comical way (more on that in a minute).

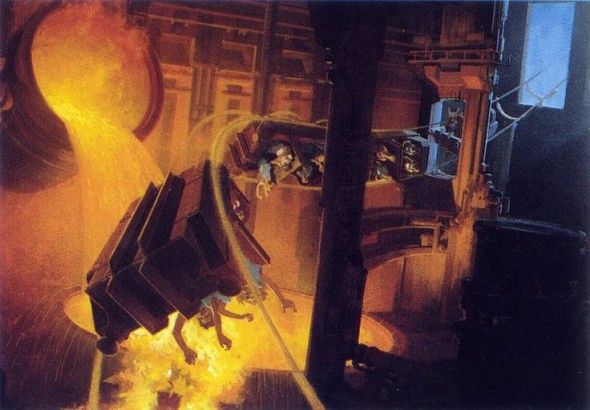

Enterprise (1870 – 1930): “The factory town of Enterprise plays host to inventions and innovations spawned by the ingenuity and can-do spirit that catapulted America to the forefront of industry.” Yay Capitalism! “Within Enterprise, those daring enough can climb aboard the Industrial Revolution, a high-speed adventure through a turn-of-the-century mill culminating in a narrow escape from its fiery vat of molten steel.”

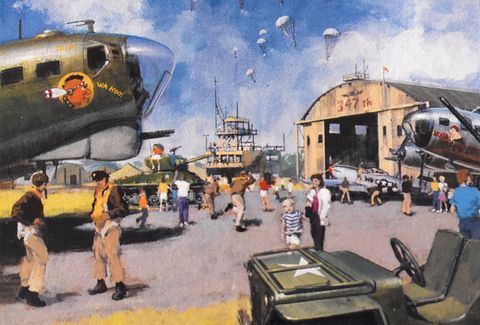

Victory Field (1930 – 1945): “The flight of the Wright brothers opened a new chapter in American history, bringing with it a thrilling exploits and military advancements.” Again, it’s pretty clear that the Imagineers weren’t sure what was going to go in this section of the park but they knew something would go there. “With the assistance of modern technology, guests at Victory Field may parachute from a plane or operate tanks and weapons in combat, and experience firsthand what America’s soldiers have faced in defense of freedom.” Victory through air combat, indeed.

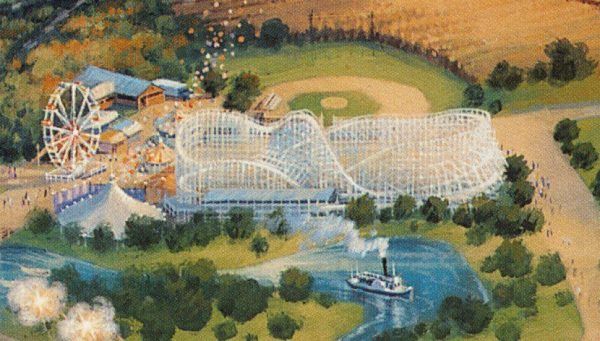

State Fair (1930 – 1945): “State Fair celebrates small town America at play with a nostalgic recreation of such popular rides as a 60-foot Ferris Wheel and a classic wooden rollercoaster, as well as a tribute to the country’s favorite pastime, baseball.” The baseball celebration is where things get really interesting: “Amid a backdrop of rolling corn fields, fans may have a hot dog and take a seat in an authentic, old-fashioned ballpark and watch America’s legendary greats gather for an exhibition all-star competition.” No clue how they would have pulled that one off but it’s clear the Imagineers were watching a lot of Field of Dreams around this period.

Family Farm (1930 – 1945): “Offering a cornucopia of pastoral delights and insight into their production, Family Farm pays homage to the working farm – the heart of early American families. Visitors see how crops are harvested, learn how to make home-made ice cream or milk a cow, and even participate in a nearby country wedding, barn dance and buffet.” Not sure about the country wedding but bring on the ice cream.

As far as the presentation part of the press conference went, things were pretty smooth. The Imagineers clearly had a vision for the new park, and it seemed to succeed in several of the ultimatums laid out by Eisner: namely that it was a more cost-efficient park (the budget would later be pegged at around $650 million, which is considerably less than parks like EPCOT cost) and that it would bring history to life in a vibrant, technologically sophisticated and above all entertaining way. But there was a hiccup when Weis addressed the crowd. “This is not a Pollyanna view of America," Weis told a room the Washington Post described as “packed [with] reporters, local and state politicians and community residents.” Weis continued: “We want to make you a Civil War soldier. We want to make you feel what it was like to be a slave or what it was like to escape through the underground railroad." Oof. This was a crucial blunder. “Within days, critics had seized on this statement as the height of presumption,” Eisner later wrote in his memoir. “I wish that Bob had phrased his answer more felicitously, but the point seemed to me a reasonable one. We had no intention of trying to replicate the experience of slavery for anyone. But we were committed to bringing history alive by telling emotionally compelling stories in dramatic ways. Somehow, we never successfully communicated that distinction. The more we tried, the more we stepped on our own toes.” Did they ever.

Another section of the press conference was devoted to questions about how Disney’s America might impact the local environment, which they handled well enough. “We fully intended to work with local officials to assure that we addressed local concerns and more than met environmental standards,” Eisner wrote later, pointing to the efforts the company had made to preserving wetlands and natural animal habitats at its sprawling Walt Disney World resort.

But it was too late. Five days after the press conference, more than a dozen of the wealthy landowners of the rambling Virginia estates to the west of the Disney’s America property had met to organize their opposition. Local environmental groups had also began to make noise. Disney’s America, just announced, was already a target. The news wasn’t all bad – the New York Times, strangely, noted the “utter exuberance” of the local community and the fact that the project could pump as much as $1.5 billion into state and local treasures over the first three decades of its operation. Tellingly, in the same New York Times report, they also acknowledged the report that Euro Disney had lost a whopping $900 million in its first full year of operation and that Disney was scrambling to restructure the park’s finances. The company was engaged in battles at home and abroad.

Undaunted, Imagineering persisted. The winter 1993 edition of WDEye, an internal magazine circulated to cast members who worked at Walt Disney Imagineering, had a cover featuring Bob Weis leaning over the model for Disney’s America, his chin just above a miniaturized Freedom Bay. Inside the magazine are a number of illuminating details: the project had an internal codename of “Project V” (the “V” stood for “Venezuela,” which some took to mean that Imagineering had begun plotting a South American expansion) and the work had been done in a restricted-access building that was a part of Disney’s Grand Central creative campus in Glendale, California, right next door to Imagineering. The building had been codenamed “the safe house.” Only a handful of Imagineers even knew of the project’s existence.

Weis began, in February 1993, reaching out to various Imagineers, asking them to do “little tasks.” He told Michael McGiveney to “research East Coast icons and collect material on the Civil War” and assigned Chick Russell the task of reaching “American innovation and baseball.” Russell made a trip to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, even though he still wasn’t sure what, exactly, he was working on. In April Weis brought the team together and told them about Disney’s America, with a warning: “What I’m about to tell you, you can’t tell others or the project will be in jeopardy.”

That level of secrecy applied to the trips the team would take to Washington, D.C. as well: “Disney insignia on luggage, baggage tags and clothing was banned, as was the use of company credit cards or anything else mentioning the Disney name. The same for discussions of their purposes in public places.” Even in this internal publication, they mention the somewhat excessive, highly critical Washington Post coverage and how the announcement was “spread across five columns of its front page.”

What makes the WDEye reporting especially exciting is that Bob Weis is quoted directly – and at length – about the project. “This is not in any way a Disneyland or Walt Disney World. It is a small-scale regional park which would be a fundamental part of what a family’s experience of seeing Washington is going to be about,” Weis began. Describing Disney’s America as “more interactive and a little more gutsy” than other Disney parks, Weis said, “We’re going to deal with real issues and the diverse population of this country as it was defined through struggles … so you’ll see some pretty rough issues dealt with in this park, as well as lots of fun things you would expect to be a part of one of our parks.” Weis continually stresses the mixture of entertainment and education, noting that in the same section of the park as the full-throated Industrial Revolution rollercoaster “will be exhibits of famous American technology that have defined our industry historically, and also new developments that will define industries into the future.”

There are also more specifics about attractions in Weis’ report – the Victory Field attractions will utilize “virtual reality technology,” while the State Fair area will “contain some of the classic wooden thrill rides of a bygone era.” This is where Weis first mentions moving the Hall of Presidents from Walt Disney World to the new park. “It will probably move to this location from Walt Disney World,” Weis wrote.

Towards the end of Weis’ remarks, he seems enthusiastic but also daunted: “I haven’t done anything like this before. It’s somewhat of an extension of what we started to do with Disney-MGM Studios and what others began with EPCOT Center, to combine education and entertainment in a new way, to try to strike a balance between a very cognitive issues-oriented park and something that’s still repeatable, fun, and interesting. It will be a challenge because we have lots of historical ground to cover, to research and to figure out how to sort through the huge historical library of what America is about and find icons we can recreate.” But other challenges loomed, something that Weis seemed to be fully aware of. He concluded his remarks by saying, “There is no way that a theme park, no matter how sophisticated it is, can truly represent a cross section of it, and we need the involvement of lots of outside people to do that. A big challenge will be to get them to come and embrace the project and feel like they have the input to be a part of it.”

Around the same time that the WDEye was published, Weis began to do just that: he and the “Project V” team began to fly to Washington, D.C. to court leaders of several influential groups to advise on the new project, including the Washington Indian Leadership Forum, the Congressional Black Caucus, the Virginia Historical Society, and the Smithsonian Institute. Most agreed to help. They even secured James Horton, an African American history professor at George Washington University, who had initially expressed skepticism, to help with a pavilion on slavery. (Months later, Horton would paint himself as the cynical voice of reason, noting that the sunny optimism of Main Street USA wouldn’t be found in Disney’s America: “I have no control, but I'll make a lot of noise if we see that kind of fantasy passed off as history.”) Eisner later wrote, “If Disney intended to build a theme park devoted to American history, they told us, they were eager to try to ensure that we did so knowledgably and responsibly.”

On January 15, 1994, Eisner convened an all-day meeting that assembled at the Imagineering campus in Glendale (it was, incidentally, a Saturday). The proposed 1998 opening date for Disney’s America was looming and the tangled mass of ideas that made up the park needed to be refined and stabilized. “The most difficult job,” Eisner told the Imagineers (according to his memoir), “won’t be to tell important stories about our history or to deliver an enjoyable experience for our guests, but to achieve both these goals without having either one dilute the other.” They began to hone the idea of Disney’s America and look at it more critically. The Industrial Revolution, the rollercoaster attraction housed inside the twentieth-century steel mill section of the park, was taken off the table because Eisner and the group feared that it would “trivialize and even demean the attempt to portray the steel mill realistically.” (The educational, interactive exhibit remained.) By the end of the day, Eisner was more committed to the concept than ever. “What we need is more edge and more depth,” Eisner announced, the general leading his team into the battlefield.

And while Virginians by and large supported the project, citing improved infrastructure for the area (unclogging Interstate 66) and the millions of dollars it would pump into the local economy (not to mention the thousands of new jobs), the cultural critics began their attack. In February a damning New York Times editorial entitled “Virginia, Just Say No to the Mouse” ran. It largely set the tone for what would follow. “Make no mistake: What the kids would remember about such an experience would be the technology and the thrills, not the history. This is not an educational undertaking; it is a business venture,” the piece read. It mocked Governor Allen’s claim that the project was the centerpiece for Virginia’s “economic renaissance.” The piece concluded: “If Disney walks away, Virginia's economy will still be sound, and its role as a custodian of important national resources will be stronger. As for parents who want to give their children history, let them -- like generations before them -- make the trip to Prince William County. Let them sit still at Manassas and listen for the presence of the dead.” Cool. A month later, a rebuttal ran in the same section of the New York Times. Its title: “Disney Can Make History Fun.”

In April 1994, another crushing blow came to the Disney’s America project, to Michael Eisner, and to the company in general when Disney President Frank Wells tragically died in a helicopter accident in Nevada’s Ruby Mountains on Easter weekend. Wells was always seen as the gatekeeper for projects, someone who could pump the breaks on Eisner’s wilder ideas and offer helpful suggestions to get them back on track. He also fought for projects he cared about and believed in, and his more level-headed sensibilities helped win over critical board members or suspicious press. Eisner lost his closest confidant and fiercest creative ally and Disney’s America lost one of its most powerful commanders.

The kind of back-and-forth displayed in the New York Times editorial pages was becoming the norm and by the summer, the fight for Disney’s America would become all-out war, with Disney on one side of the debate and those lobbying for environmentalism, historical reverence, and the peace-and-quiet of their wealthy rural community on the other. On May 11, a group called Protect Historic America (not exactly the catchiest name) was officially launched. They were funded, in part, by the Piedmont Environmental Council, and led by ale University professor emeritus C. Vann Woodward and Duke University scholar John Hope Franklin, and had a number of well-known, media-savvy members, including Lincoln biographer Doris Kearns Goodwin, historian David McCullough (who had recently narrated the popular Ken Burns documentary The Civil War) and Richard Moe, head of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, someone who Eisner saw as something of a personal adversary. (The National Trust for Historic Preservation had already come out against the project, its funding coming from those wealthy families in the area.) Woodward said that Disney’s America "would be an appalling commercialization and vulgarization of the scene of our most tragic history, and I would deplore it." McCullough went further: "Would we as a country want a theme park at Normandy Beach? Would we permit that? Would we, in the name of creating jobs, make splinters of Mt. Vernon?" Disney responded by noting that they had several historical advisors on staff, paid $100,000 to the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Battle Sites before these attacks even began, and were committed to authentically capturing history and maintaining the surrounding environment. “"It's unfortunate that a group of historians would prejudge the project and draw conclusions about the historical content and potential impact of the park without having the necessary facts," the statement read.

These attacks did what they were meant to do: they weakened public support and called into question the validity of the entire operation. “It no longer mattered that the park didn’t really sit on a historic battlefield; or that by widening the highway that ran by our site we would be improving what had long been a nightmarish bottleneck for commuters; or that the road leading to Manassas already contained a dense, tacky strip mall development far more intrusive than the park we envisioned building,” Eisner later wrote. Opposing Disney’s America had become, in Eisner’s words, a “cause célèbre.” And he had a point. Magazines like Conde Nast Traveler ran splashy stories like “Making a Stand,” with members of the Protect Historic America group glossily framed in a beautiful, moody photo, storm clouds gathering in the distance.

Around the time of the Protect Historic America press conference, Weis and Eisner had convened his own group, which included James Billington of the Library of Congress; the Reverend Leo O’Donovan, the president of Georgetown University; Sylvia Williams, director of the National Museum of African Art at the Smithsoaian; Rex Scouten, the chief curator at the White House; and several other prominent critics and historians. Weis had the group meet at Walt Disney World, gave them the rundown of what Disney’s America could be, and let them offer their ideas and share their criticisms. Together, the group toured several EPCOT pavilions, including the American Adventure, a 25-minute, audio-animatronics-filled show that would act as the kind of precursor to Disney’s America, covering similar landmarks in American history including the Civil War. They weren’t exactly fond of the American Adventure, with George Sanchez, a history professor at the University of Michigan, telling Weis and Eisner, “My general impression is that it’s not the America I know, neither from the scholarship nor from my own perspective.” Others agreed and echoed the critiques that many were lobbing at Disney. “I was surprised by the intensity of their reaction, but not upset by it. Disney’s America remained very much in the early planning stages, and the whole purpose of this meeting was to solicit more input and make it better,” Eisner wrote later. He told the group that “Disney’s America has the potential to redefine the Walt Disney Company more than anything we’ve done,” urging them to help the company achieve excellence and accuracy. (They were more impressed with the Hall of Presidents at the Magic Kingdom, which had recently been reworked with the help of Maya Angelou and Bill Clinton.) By the end of the trip, the historians got the sense that Disney had really wanted their input and that Weis and Eisner were listening. Eisner felt “reinvigorated by the project,” he later wrote, telling the attendees, “I hope this is the beginning of our dialogue. We spent five years making The Lion King and still didn’t have it completely right. But we got a lot closer. This park will change and evolve over the next several years and we want it critiqued. It’s much easier to change something in the planning stages than it is once it’s built … This has been very valuable. It has simulated a lot of ideas. It has refocused me.” Eisner was at least right about one thing: Disney’s America would be critiqued, endlessly.

Eisner took a trip of historical sites in Washington, D.C., visiting places like Mount Vernon but also visiting the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, which impressed Eisner with its immersion and its emotionality. (“The museum’s creators used many of the dramatic tools and techniques that Walt Disney had pioneered – film, animation, music, voice-over narration – in this case to recreate and evoke the horror of the Holocaust. These were the same tools that we intended to draw on for Disney’s America,” Eisner wrote later.) He began to get a sense of how Disney’s America would fit in amongst the landmarks, libraries and historical museums.

At around the same time, Disney mailed flyers to Virginia residents. There’s a black-and-white cover of Governor Allen at a bill-signing ceremony that launched the partnership with Disney’s America (signed earlier that spring) and a letter from Mark Pacala, the General Manager of Disney’s America. It read, in part, “First and foremost – thank you for your support over the past several months. Since announcing our plans last November, we’ve spoken with over 10,000 citizens of Northern Virginia. We’ve had one-on-one conversations over coffee and broader discussions with larger groups. We’ve shared our thinking and listened to your concerns. In almost every instance, we’ve come away gratified and impressed by your enthusiasm for Disney’s America. The fervor and willingness of so many of you to make your view known to the news media and your elected officials have played a major role in winning support from the General Assembly.” Pacala went on: “Disney’s America is committed to working with public officials, citizens, and independent experts to address such issues as traffic and the nature of future development. It is also essential that those of us at Disney’s America continue to listen to your views and concerns as we move ahead with the project. It is important for you to know more about Disney’s America and the Walt Disney Company. That’s why we’ve created this newsletter.” Pacala encouraged residents to stop by the Disney’s America office in Gainesville (you could even see a model of the park and official artwork) and thanked the community for their support. “Disney’s America is determined to be a good neighbor, and we appreciate the open hands and open hearts that you have extended in welcome.”

Next to Pacala’s letter in the newsletter is a section devoted to “traffic facts” (included: extremely 90s clip art), mean to lessen the anxiety about threats of increased traffic and on the already overworked Interstate 66. The chipper tone is pretty encouraging. “The improvements will immediately provide a net increase in roadway capacity. The expansion in capacity will exceed traffic traveling to and from Disney’s America” is one of these “facts,” along with, “Disney’s America will generate 60 percent less rush hour traffic in the year 2000 than a 2,800-home residential project previous approved for the park’s site.” Yay?

Inside the newsletter are more articles from elsewhere in the company meant, designed to make Virginia residents more comfortable with the proposed project – one is about environmental initiative The Disney Wilderness Preserve, another is about Disney’s commitment to Community Service, and another is about The Disney Channel (“More than Mickey Mouse”), I guess to emphasize the range of topics and subject matters that the company can successfully navigate. On the back is a “Virginia History” quiz, a note that the county “should earn $11.9 million in park’s first year” and a small advertisement for Disney’s America Community hotline. There’s a little tab attached to the newsletter toor. “If you would like to keep informed about Disney’s America, please fill in and return the attached card,” it reads. There are three options you can check off: “I support Disney’s America. I agree that this project is good for the region,” “I would like to attend events supporting Disney’s America,” and “I will support Disney’s America by writing letters and speaking at public hearings.” Disney was looking to recruit some good soldiers.

All of the goodwill Disney had accrued from Virginia locals and politicians, plus all of the reinvigoration Eisner was experiencing, came crashing down in early June. Eisner was in Washington, D.C. to attend a senate subcommittee on public lands (and Disney’s America’s proximity to historically protected sites), urged on by the opponents of the project and instigated by Senator Dale Bumpers. The hearings would be public (they’d be broadcast live on CNBC) and Eisner was worried that public sentiment would take a hit. He agreed to an interview with the Washington Post, a publication that Eisner had perceived as overtly hostile to Disney’s America. He later admitted to entering the conversation with “a chip on my shoulder – never a good idea,” and the resulting article (“Eisner Says Disney Won’t Back Down”), which ran on the front page of the paper, was downright disastrous. "I expected to be taken around on people's shoulders," Eisner admitted (he later said this quote made him “cringe”). Of the historians judging the project, Eisner fired back: “"I sat through many history classes where I read some of their stuff, and I didn't learn anything. It was pretty boring." It didn’t matter that Eisner had some good points, like about how critics were harshly judging a project that was still in the model-and-mock-up stage (“This concept of reviewing a movie before the script is written or reviewing a book when you've only got the table of contents is pretty shocking to me”), he came across as entitled, boorish and déclassé. It was not a good look, for him or the project, already mired in controversy. “My comments made me sound not just smug and arrogant but like something of a Philistine,” Eisner wrote in his memoir. He also claimed, rather unconvincingly, that he thought the interview was on background and that he wouldn’t be quoted directly.

While in D.C., Eisner continued to lobby senators and congressmen, inviting many to a private screening of The Lion King. Exiting the theater, the senators and Eisner were met by angry protestors. He could not win. A week later the Senate Energy and National Resources subcommittee was held. Attended by “dozens of journalists and TV cameras and some five hundred curious onlookers” (according to Eisner), it saw critics like McCullough give impassioned testimony on the folly of the project and how sacrilegious it would be to have something so garish built next to a site as sacred as a Civil War battlefield (even though, it was established, they weren’t at all close). Most of the senators, both Democrat and Republican, sided with Disney and thought this was more of a local matter. Governor Allen gave maybe the most impactful speech, saying, “I think I’m on solid ground in suggesting that Senator Bumpers’ committee wouldn’t have held a hearing if opposition to this park had not become a crusade among the well-connected folks who don’t want it located within 30 miles of their neighborhoods,” he said, referencing the well-to-do landowners who were funding the groups fighting Disney’s America. “With all other arguments faltering, these opponents turned to historians who don’t like the idea of history-based theme parks … They have the same right as other Americans to express their points of view. But in arguing that this project ought to be blocked because they fear that the Walt Disney Company will not interpret history to their satisfaction, these folks are practicing censorship.” There were some notable detractors on the committee itself, including Senator John Chafee, but Disney had largely come out on top, either by the senators’ support or their indifference. The outcome was clear: the federal government would not interfere with the development of Disney’s America.

A week later, the Protect Historic America group took out a full-page ad in the New York Times, reprinting some of Eisner’s more incendiary quotes from his Washington Post interview with the headline “The Man Who Would Destroy American History.”

In mid-July Eisner underwent emergency quadruple bypass surgery after the CEO complained of a tightness in his chest and doctors discovered “coronary blockages severe enough to warrant an immediate operation.” Eisner was clearly under a lot of stress – Wells’ death had initiated a power struggle between Eisner and his lieutenant Jeffrey Katzenberg that led Katzenberg, who was overseeing the resurgence of the Disney animation unit, to strategize his exit, and Eisner had just unsuccessfully lobbied prominent board member Sid Bass to okay a costly acquisition of NBC. While unexpected, the surgery wasn’t a complete surprise. As Eisner woke up after the surgery, climbing through the foggy haze of anesthesia, he later said he had a single thought: That’s the best night’s sleep I’ve had in a year.

After the surgery, Eisner was forced to cancel a number of important, Disney’s America-related trips he had planned for the following month – to regional theme parks like Fiesta Texas in San Antonio; cultural events like the Pueblo Indian Dance Ritual in Santa Fe; and important conferences like one Bob Weis had arranged with Maya Angelou and prominent black leaders and historians. On Friday, August 5, exactly three weeks after his surgery, Eisner attended a meeting about Disney’s America at the Disney lot in Burbank. They discussed a possible name change to Disney’s American Celebration, since the name Disney’s America rubbed people the wrong way (Eisner admitted it was their first mistake) and a series of protests that the various organizations had planned for mid-September. At the end of August (right before announcing that Katzenberg would be leaving the company), Eisner was handed an updated financial projection on Disney’s America.

This thick, bound “Feasibility Review,” dated August 16, 1994, is incredibly insightful, offering a rare peek behind the corporate curtain. It’s broken down into several segments, including Revenue, Investment, Operating Costs, Summary Economics, Schedule and Next Steps, and contains numbers you’d never publicly see, like the $66 million the company spent for “entitlement and concept development efforts” to deflect the opposition or the new, 1999 opening date. There is also a page that details the “Key Changes from October 1993,” when the project was originally launched (and announced the following month). The 10/93 assumption for the park’s creative positioning was “Regional Park with history theme;” the 8/94 assumption had changed to “National History Park with extremely high expectations for historical accuracy and sensitivity.” Under reinvestment, there’s a note: “WDI believes significantly more needed.” And most tellingly, under performance, the following: “Domestic parks down in attendance, Poor Euro Disney results, 5.7 million steady state attendance, no real price increase.”

In the product description outline for Disney’s American Celebration (as it is repeatedly referred), the lands have been re-named and new/different attractions detailed. Victory Field has become Service and Sacrifice, with Soldiers Story, described as a “time machine through American conflicts;” Immigration Story was to be “1/2 ride, 1/2 Muppet film;” Streets of America would be broken up into region and food; and Disney’s America Live would feature a State Fair Arena, to be home to “hog calling, races, roping demonstrations.” There’s also a weird reference to the Honey, I Shrunk the Audience theater. The report includes sobering statistics about the area’s winter climate, with a projected 8-week closure from “Jan. 2 to March 1,” with another “47 weekdays in late November, early December and early March” (they stress that they’d still be open in late December “to capture vacation market Christmas/New Years’ weeks”). It’s noted that during this time they’d lose “national and half of regional tourists during winter close” and that it would be a “challenge will be to retain base cast members,” with a break-even attendance on base day being 2,200 guests. The report compares the mixture of attractions to Disney-MGM (referred repeatedly in the document as “Studio Tour,” its original conception) and the soon-to-open Animal Kingdom park in Florida. And you could tell Disney’s American Celebration was lacking in every department.

By the end of the report, which also alludes to the golf courses that would have been on property and the possibility of selling Disney Vacation Club rooms at the hotels, the conclusion was made that the park would take more time and cost more money than they anticipation. They could even be operating at a loss, like Euro Disney. There are a pair of “alternate scenarios” at the back of the report. “In order to improve both long-term repeatability and project economics, it may be necessary to re-orient the concept either towards live entertainment and festivals or a higher mix of rides,” the report summarized. Disney and the Imagineers would have to either stick with Disney’s American Celebration and “increased entertainment and festival emphasis,” with a reduction of “capital investment in favor of operating entertainment,” or pivot to something they refer to in the feasibility review as Disney’s America Plus, with “increased ride emphasis” and “increased capital investment.”

Eisner considered sending the team back “to conceive a scaled-down version of the park that made more economic sense.” Disney was winning key decisions when it came to transportation and environmental issues, and in early September, 10,000 local supporters came out for a county fair that Disney held in Prince William County “to rally the troops and counter the critics” (according to Eisner). A few weeks later, however, Eisner decided to pull the plug. “Largely through our own missteps, the Walt Disney Company had been effectively portrayed as an enemy of American history and a plunderer of sacred ground,” Eisner wrote later. “The cost of moving forward on Disney’s America, we reluctantly concluded, finally outweighed the potential gain.” On The Imagineering Story, the terrific documentary series on Disney+, Eisner said, “We were at the wrong place, at the wrong time. And the people we were fighting had the ink. They came after us every day in the newspapers. Had Frank been alive and had I been healthy and had we not just bought ABC, we would have plowed through. But I just didn’t have the stomach.” Interestingly, Disney didn’t buy ABC until the following summer, on August 1, 1995. Eisner probably meant that he was still fighting with Katzenberg, which was very true at the time. Either way, he had more than enough stress.

Thousands, including, unsurprisingly, Ralph Nader, streamed into Washington, D.C. on September 17, 1994, to protest Disney’s America. People held signs that read “Mickey didn’t free the slaves, learn the truth” (did anyone actually think that?) and chanted “Hey Hey, Ho Ho, Disney’s Got to Go,” briefly pausing in front of the White House for a charged photo op. Nader criticized Disney’s “philosophy of becoming its own private government,” citing the controversial Reedy Creek district in Florida that houses Walt Disney World. “If it’s not stopped, Disney will be a model for other corporations,” Nader warned the angry throng. Courtney Gallop-Johnson, founder of the Black History Action Coalition, disliked Disney’s secrecy when it came towards their approach to slavery. But by the time the protestors filled the streets of Washington, D.C., Disney had already made its decision to abandon the Virginia theme park.

On September 28, 1994, Disney publicly waved the white flag of defeat. In a statement, Peter Rummell, said that, "Despite our confidence that we would eventually win the necessary approvals, it has become clear that we could not say when the park would be able to open, or even when we could break ground." Just like the announcement to build Disney’s America had leaked, so too had the announcement that they were giving up, which meant that key allies to the project, like Governor Allen, weren’t briefed beforehand. "I would characterize our reaction as absolute shock," Robert T. Skunda, the state Secretary of Commerce and Trade, told the New York Times. Skunda had, just the week before, won the approval of the Prince William County Planning Commission and the regional Transportation Planning Board, clearing two substantial hurdles to the project’s development.

Those who opposed the park were overjoyed. “"We do feel good about it," James M. McPherson, from Protect Historic America told the New York Times. "Disney recognized what it was costing them in terms of image, public relations and the potential for a long, drawn-out controversy and lawsuits from environmental groups. They decided to respond to all the criticism and what we have emphasized all along, location." (Weis reflected on The Imagineering Story, “It almost didn’t matter how good we got at the ideas, the land was always going to drag it down.”)

In announcing the end of the project, Disney (and Virginia) still remained optimistic. In the official statement, Rummell said, "In our mind, Virginia would still be an ideal place for this park." And Skunda told the paper that Disney was hopeful they would find a new spot for the project in the state. Eisner sought to broker peace with some of the project’s most outspoken critics, including McPherson and McCullough, who agreed to advise on a future iteration of the historical park.

Less than a week after the park cancelation was announced, officials from Pennsylvania began to woo Disney. “We are putting together a presentation package for the governor to send to Disney," said Dennis Curtin, a state Commerce Department spokesman, told a local paper. The report noted that West Virginia and Maryland had already made bids on the project, so far unsuccessfully. Claudia Peters, a spokesperson for Disney’s America, reiterated their commitment to Virginia. “"Virginia is still our first choice and we are committed to finding the appropriate site in Virginia," Peters told the outlet. Nothing panned out, anywhere.

Years later, Disney also briefly considered buying Knott’s Berry Farm, down the street from Disneyland in Buena Park, and turning that park into a version of Disney’s America, which made sense given that park’s already strong commitment to Old West iconography and theming. When the park was up for sale in 1997, Disney made a go of it, but the property was ultimately sold to Cedar Fair, owners of the coaster-heaven Cedar’s Point in Ohio. Legendary Imagineer Tony Baxter has recently said that, when Disney’s acquisition of Knott’s was on the table, Disney was going to expand the monorail line, connecting Knott’s and Disneyland via “the highway in the sky.” Ah to dream.

And eventually Disney’s America did get built – sort of. When Disney’s California Adventure opened on February 8, 2001, it contained a number of elements familiar to those who had followed the saga of Disney’s America. Condor Flats, complete with a blockbuster, aerial-themed attraction (Soarin’ Over California) and a vague, World War II-ish theme, was a variation on Victory Field; Disney’s America’s Lewis and Clark river raft attraction became Grizzly River Run, a Gold Rush-set adventure that would leave you sopping wet; the State Fair area of Disney’s America was transformed into turn-of-the-century Paradise Pier (with the “wooden” rollercoaster and Ferris wheel); Bountiful Valley Farm was a decidedly more boring spin on Family Farm. Somewhat tellingly, all of these areas of the park have either been radically altered or removed completely – Condor Flats became Grizzly Peak Airfield, Paradise Pier became Pixar Pier (its old-timey rollercoaster became an Incredibles-themed attraction) and Bountiful Farms was demolished, becoming home first to A Bug’s Land and later Avengers Campus, which was set to open earlier this summer

Another idea from the proposed Disney’s America that had an unlikely resurgence was the idea of staying inside your favorite Disney theme park, which would be utilized at the Grand Californian in Anaheim, with rooms that buttress the Disney California Adventure resort, and more staggeringly with the Hotel Miracosta at Tokyo DisneySea (both hotels opened in 2001). Unlike the Disney’s America plan, though, these hotels are centrally located and not scattered throughout the park.

Fallout from the death of Disney’s America was swift and lasting – project architect Bob Weis was dismissed from the company, only to return years later (he’s now President of Walt Disney Imagineering), Pacala was gone by the end of 1994 and Rummell left the company in 1997. Wells and Katzenberg were gone by the time of the project’s defeat. Eisner was left alone and heartbroken. This was, after all, a project that Eisner thought could transform the company and would be key to insuring his legacy. “There was no project during my first decade at Disney about which I felt more passionate about than Disney’s America,” he later wrote. At the end of his chapter on Disney’s America in his memoir, Eisner mused: “A good idea never dies and I had no intention of giving up on a historical park permanently.” It’s questionable as to whether or not Disney’s America was ever a good idea, but like any war, the battle for Disney’s America left deep, aching scars. Eisner lost his nerve, instead investing in more conservative, smaller-scale projects that lacked the ambitious and the lunacy that made Disney's America such a unique gamble. The project also holds a special place in the history of Disney themed entertainment. 25 years later, no project came closer to completion or was mired in more controversy than Disney’s America.

For more on the past, present, and future of Disney Parks, check out our interview with The Imagineering Story director Leslie Iwerks.