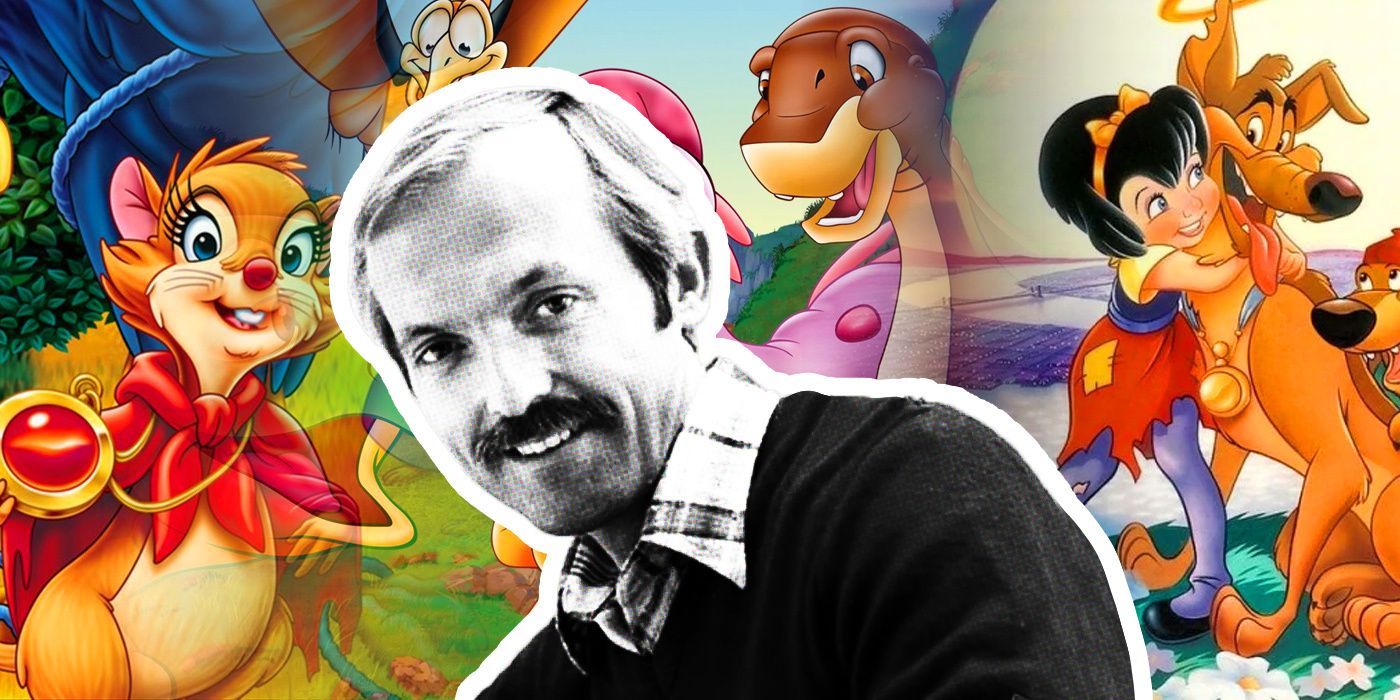

It is difficult to imagine a time when Disney Animation stood on the precipice of decline. Timeless cartoon classics from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to Encanto seem to bookend an age of film history that calls to mind words like innovation and success. Looking back, however, one may find it shocking that in 1979 a young animator, hailed by many as the next Walt Disney, decided to abruptly leave and start his own studio. Over a dozen animators left with him in a mass resignation, and they left a hollowed-out Disney Animation in their wake. A disastrous fate seemed all but sealed. The animator in question? Don Bluth.

As the Greatest Generation entered their golden years in the 1970s, so too did many of the original animators responsible for Disney’s massive success in the 1930s and onward. The remaining members of the Nine Old Men, a cadre of artists known for their pioneering work under Disney himself, were preparing for retirement. As their era came to a close, new artists were ushered in to pick up where they left off.

Bluth arrived at the studio in 1956 at the age of 18 to work as an in-betweener on Sleeping Beauty for one of the Nine Old Men, John Lounsbery. He was responsible for the drawings that came between keyframes in Lounsbery’s animation. Bluth left Disney shortly after to partake in religious mission work, but returned to the studio for summers through 1962 and rejoined full-time in 1971.

Bluth soon grew frustrated at Disney. He lamented that the process of making an animated film mystified him. “We didn’t know how to create ‘texture’ in a film, to place a slow sequence next to a fast one, or how you put a sad sequence next to a happy one,” he remembered in On Animation: The Director's Perspective Vol 2. “We could only do individual scenes.” He bemoaned the fact that animators couldn’t even touch production equipment because only union workers were allowed at the time. At one point he asked one of the Nine Old Men, animator Frank Thomas, how they made the water effects in Fantasia appear so clear and realistic. Thomas responded, “You know, no one ever wrote that down.” To that, Bluth recollected, “I was just astounded.”

In response to this, Bluth doubled down on his study of animation production. It started as a small filmmaking project in the garage of his home in Culver City. The first iteration was The Piper, a short animation based on a limerick written by Bluth’s brother Toby. After recognizing the flaws in The Piper, Bluth went back to the drawing board on a new project called Banjo the Woodpile Cat about a kitten who runs away and ends up on an adventure in Salt Lake City. In his pursuit of cinematic knowledge, Bluth enlisted other Disney animators to learn with him. These animators became known as “Bluthies,” converts to Bluth’s philosophy of animation. Among them were many of the studio’s women animators, seeking a rare opportunity to learn about production. Bluth claimed that the women felt a sense of loyalty to him “because the atmosphere at Disney is sometimes oppressive to women.” He continued, “For years, women have been assistant animators there, but they’ve rarely let them get higher.”

As the Bluthies grew in number, so too did their detractors. Animator Burny Mattinson started at Disney around the same time as Bluth in the 1950s and was among those invited to visit the makeshift garage studio. Mattinson was not charmed by the expanding Bluthie group, saying in Walt's People Vol 12, “Don was kind of a cool fish in a way.” He continued, “Bluth sort of built a clique up of just his people around him and really kind of isolated himself.” Others at the studio were equally dubious. “His identification with the iconic Walt Disney was so strong he even grew a thin mustache and at one point affected a pipe,” author and animator Tom Sito described in Drawing the Line, “No one was sure whether Bluth was joking or not.”

While Bluth was primed by Disney management to lead a new generation of animators, many of the younger artists at the studio became his biggest critics. A new crop of animators had recently arrived at the studio fresh out of the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). In 1975 Disney artists Ken Anderson, Marc Davis, and Eric Larson launched a program at CalArts that would allow the old guard at Disney to train a new guard of animators. They created the Character Animation Program, and shortly after many of the graduates of that program became Disney artists themselves. Larson also spearheaded a Talent Development Program at Disney. With his prestige as one of the Nine Old Men, he guided new recruits and became a beloved mentor to many budding artists. Among his projects with his trainees was a Christmas short film The Small One, the project that would ultimately cement the clash between the Bluthies and the Non-Bluthies.

The Small One tells the story of a young boy who reluctantly parts with his treasured old donkey. The sale of this donkey ultimately plays into the story of the birth of Jesus. Larson prepared to direct and began working with the young trainees on the short film. Then “there was a coup d’etat over the weekend,” CalArts alum John Musker described. Larson was no longer in charge, and he was being replaced by Bluth. All the storyboards developed for the short had been stripped from the walls, and new model sheets were up in their stead. According to Mattinson, Head of Animation Don Duckwall told Larson, “Bluth has gone to [Disney CEO] Ron Miller over the weekend, met him here at the Studio and has convinced him that he would be better to do this picture.” Mattinson added, “Eric was almost in tears.” Bluth claimed in later interviews that he was actually appointed to work on the short and was stuck in the middle. “What a dilemma for me,” Bluth stated in retrospect.

This change in leadership did not endear Bluth to the CalArts alumni, and they would soon become a thorn in his side. When Bluth came on to direct The Small One, all the trainees on the short were forced to jump through new hoops to prove themselves as adequate animators. A memo was sent to them which requested a character animation sample that would display an emotion. “Whichever emotion you select should be played honestly – go for sincerity or believability” the memo read. “Don’t camp or ham it up. The assignment is not for corn, but honesty in acting.” In a humorous show of defiance, fellow CalArts grad Brad Bird caricatured an image of himself onto this memo with a speech bubble that read, “But I like corn.”

The factions were set. The CalArts group was driven by humor and personality, and Bluthies were focused on technical style. Bluth was additionally pushing the idea of rotoscoping, which in animation involves using live-action reference footage of actors to trace action frame by frame. To the CalArts group, this took away all the creativity of their work.

Ultimately, Bluth’s goal for the studio was to return to the classic Disney repertoire. He claimed that he was desperate for his artists to “come up to the quality we needed.” This disconnect led another of the CalArts alumni Bill Kroyer to speak directly to Disney CEO Ron Miller. He expressed concerns about the direction the studio was going. Kroyer set up a screening for Miller introducing him to other styles of animation from outside the Disney company. When Bluth found out, he was livid.

Kroyer, along with Musker, Bird, and other artists Jerry Rees, Henry Selick, and Dan Haskett, shared adjacent rooms in the famous D-Wing of the animation building. After Kroyer went to Miller, Bluth came down to see them. Musker recounted Bluth’s words to the group: “This place is a rat’s nest of rumor and innuendo, and it’s got to stop.” When they asked to collaborate more, Bluth doubled down. “He basically said, ‘The studio’s built on a system of kings and serfs. And guess what? You’re a serf.’” The CalArts group that shared that room came to adopt the moniker, and to this day jokingly refer to themselves as “The Rats’ Nest.”

With so much upheaval and a lukewarm review of The Small One by veteran Disney artist Woolie Reitherman, Bluth retreated from his work as a director at Disney. He refocused his effort on his garage project Banjo the Woodpile Cat. He even attempted to get Miller to back the project, but the studio head turned him down. “By that time I knew that I was going to leave the Disney Studio,” Bluth said.

Around the same time, Bluth’s longtime collaborator Gary Goldman received a call from former Disney executive Jim Stewart, who was working on a new company called Aurora Productions. Word had gotten out that Bluth was unhappy at Disney and Stewart was interested in financing a new studio with him and producing an animated feature film. “Just weeks before this call, Ken Anderson had brought a book to my office called Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH,” Bluth said. The idea had been shot down by Disney, so Bluth pitched it as the first feature of his new studio. After showing investors Banjo the Woodpile Cat, they officially secured the funding.

“I called a meeting for everyone who was working on Banjo and said, ‘Guys, we’re taking our short and leaving. We’re not asking you to leave, but you are welcome if you want to come with us.’”

On September 13, 1979, Bluth’s 42nd birthday, he officially resigned from Disney. Goldman recalled, “11 more artists resigned the following day and three more came aboard the following January.” As Mattinson remembered, “[Bluth] had set it up with all these different animation people. He had told each and every one of them that he wanted them to come in one after another into the boss’ office (which was Ed Hansen at that time) to quit.” He continued, “I guess he wanted to make it feel like they were really going to walk out, and they were going to cripple the Studio. Well, they walked out, but they didn’t cripple the studio.”

In the aftermath, Miller made a speech to Disney Animation staff which started with, “Now that the cancer has been excised…”, expressing his frustration at Bluth’s sudden departure. With so many artists gone, the impact was felt at the studio as they worked to finish The Fox and the Hound. As a result, the film’s release was pushed back six months from Christmas 1980 to summer 1981. Over at the Bluth studio, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH was released as The Secret of NIMH, which was critically acclaimed, but a box office defeat.

The bad blood between the Bluthies and Disney still persisted through the years. During an animators’ strike in 1982, strikers from Bluth’s studio showed up at the Disney studio gates dressed like characters from The Secret of NIMH. Sito described, “As Disney CEO Ron Miller drove through the picket lines at Disney, young Bluth animator Dave Spafford leaped onto his car’s hood, gave Miller the finger with both hands and shouted, ‘Up yours, Football Boy!’” Miller was a University of Southern California football player.

In the decades that followed, Bluth was responsible for many popular animated films including An American Tail, The Land Before Time, and Anastasia. His goal to “help build the future of animation” came true in the form of teaching courses on animation to young hopeful artists at the Don Bluth University. Bluth said his intention was not to hurt Disney when he left the studio. As a result of leaving, however, he provided some necessary competition that challenged Disney to grow into one of the most prosperous eras in animation history: the Disney Renaissance. As Eric Larson said in response to his departure. “I welcome the competition. It’s what we need.”